Biodiversity is an abstract concept, interview with Mia Couto

Two hours with Mia Couto in an engaging conversation that covers various aspects of his interests and career, his affective geographies, the diversity of peoples and their ways of life as inspiration for the stories, the environment, and the development model to be discovered, and how to treat nature not as a “resource”. We talked about hard times of violence, and the utopia of Mozambican Independence. Literary subjects do not predominate, although the Mozambican author wishes he had more time to dedicate to writing. Also thinking about how to take the pleasure of reading further and how to help bring out new writers. A writer in the terrain.

How do you manage to articulate the busy world of a writer, full of interviews and travels, with life as a biologist in Mozambique?

It is difficult. Before it was a problem, now it’s an anguish. I must solve it by taking time from somewhere. The point is not to have more time, because we invent the time we have, it’s more to be our own time, which the writing asks of us. Time to be with the characters. It is inevitable that I carry problems, which makes me less available for the stories.

And how do you plan to solve this?

To write more full time I need to create conditions in my job so that I can continue to assist the company and work in the bush as a biologist, which I enjoy very much.

Is being a biologist also a tool for writing?

Yes, fieldwork is very enriching because of the contact with diversity. With this work, I cross Mozambique from north to south, often in tents, close to people’s lives. I talk to them and collect stories that are the nuclei for other stories.

Do you prefer any particular territory or ethnicity? One senses sometimes in your writing the animism and the invisible world of the Macuas, and the villages of religious rituals.

This religiosity is a kind of common ground, although it has variants. It feels good to be in the region where I was born (the Beira area). Something reminds me of the languages spoken there, even though I don’t speak them anymore, but I believe I would soon be able to start again. It’s funny how important it is to know this childhood music.

Mia Couto, photo by José Eduardo Agualusa

Mia Couto, photo by José Eduardo Agualusa

In Defense of the Environment

As a biologist, how do you see the demand for resources and the picture of Mozambique as a possible economic power? Are “development” and sustainable agriculture compatible?

That duality is badly drawn. I don’t know, if is it related to this development model, or whether there are other happier ones. But we end up accepting it as the only possible model. Maybe it’s a utopian thing, but it has to be said and thought about. There may be environmental problems, but the big issues are social: we must think about how lifestyles are disrupted, and entire cultures torn out of their social and historical habitat. The solution cannot be to leave it alone. There is the derisive idea that things are fine because communities stay there, but they are within this model and are pushed into very aggressive modes of survival.

Sometimes people use resources unconsciously, as in the case of mangroves.

There used to be management and proper codes, and even sacred areas were spared. For example, in these mangroves, the fishponds are being assaulted by the communities themselves, who need to survive, and fish with mosquito nets, cutting where they didn’t cut before.

Mangal near Pemba, photo by António Gouveia

Mangal near Pemba, photo by António Gouveia

The phenomenon of land grabbing - attacking cultivated areas to massify farms - condemns populations to starvation. Does the southern hemisphere produce less to sustain the renewable energies of the north?

It obeys fashions. Biofuels were a byword, and it didn’t come about to the extent that was thought. But the issue is there, even to a lesser degree.

How do you combat this exploitation?

This is almost a psychiatric issue, you must tell these people how you can fight it, but not like a ghost, so that it doesn’t sound like: “These guys are holding back development, these guys are not looking after their country, they are preventing people from getting out of poverty with this speech”. Even in the name of the people themselves, you end up pushing them into a dead-end situation.

To dependency?

You must have some creativity and realize that there comes a time when you must negotiate. For example, again with the mangroves, if we say “We must defend biodiversity” we are not even going to get the support of the communities, biodiversity is an abstract concept. It is another thing to alert those who oversee the economy - who are, obviously, not only the nationals - and speak in their language, in economese: “If you lose the mangrove, you lose the shrimp. One of the country’s main exports ends up being at risk. To warn that the very logic of profitability of this model is at risk with this savage way. I am not a member of NGOs, some are serious but most of them live off feedback, they can be companies in disguise, and they are discourses that repeat themselves. An alternative discourse that may emerge has to gain space and time and have the possibility of tactful retreat. Without that dialogue it doesn’t work, they don’t know your language, and they don’t think your way.

Do you end up playing this intermediary role?

Yes, at the risk of being accused of being transigent, too open, and avoiding confrontation. Do I think this has to change radically? Yes, and what do I have to suggest? I don’t know, but there are things you can think about. For example, what we call “resources”. The word is wrong in the first place, it means that we are legitimizing an idea that what is there, whether renewable or not, exists according to our needs. As if the human species was made to make use of it, accredited by some divine order.

And the way we call it, human resources? They are people!

But the environmental impact companies - and Mia has a company in this area - have many limitations, because of the clear promiscuity with the clients who commission the studies. Do you feel any frustration with this?

Environmental impact firms are paid by the client themselves, one can question the propriety of this process, yes. What would be right is for companies to pay the state, which would constitute a fund, to appoint a company that would be comfortable failing a company. We realize that this is a limitation. There are cases that we don’t accept in the first place, and others that we fail or force to be redesigned.

On the issue of Portucel’s 300,000 hectares, have you managed to minimize anything?

It is still in progress.

They could show that eucalyptization is a repeated mistake…

The planting projects have rules established by the World Bank to be followed. Today I believe that these criteria are among the best constructed, from a technical point of view, for the defense of the environment. If they were respected we would be much better off. What is missing is the capacity to control and to do some monitoring. Portucel had to redesign its own project. Where communities don’t want it, or where there are native forests, they don’t enter, there is containment.

Do you feel like a fighter on these issues?

A bit, in the struggle to take advantage of fracture zones to occupy the ground.

If otherness were a thing to learn and not a threat, what would be interesting to value outside the hegemonic logic that “this is the only model”? What would we have to learn from these other ways of life, other economic and socio-cultural models other than the economy of the crescent?

It seems like a very philosophical thing - and I am a man who comes from a mixed culture - I notice that for me it was very beneficial to have learned the need for harmony with others, with space, living with the dead, etc.

Not talking about nature as a “resource” but as a friend?

Or as something that has no name. One of the difficulties I have in the field is saying I’m a biologist and I’m working in nature. It has no translation into the local languages.

Are we beginning to worry?

With this more holistic side and human understanding, it seems we are also looking for it. But these people already live with a certain understanding of what surrounds them. With a certain more permissive religiosity, which is not guided by the Book, whatever it may be. There is a relationship that seems to me to be freer between the body. People seem happier.

How do you defend that without defending a certain obscurantism? For example, if electricity exists, isn’t it better to be for everyone?

But that’s the deception that makes people who live in rural systems, in poverty, very needy, believe that this model answers everything. That’s the illusion, that in order to have water, energy, or infrastructure they have to pay and swallow all the gum. I don’t know if there is a way to do it differently.

And behind that come all the other needs that are created.

The problem is that those who don’t have a tap, don’t want to have just the tap, they want to have a house and another kind of life. It’s like telling a child not to date a certain person. The right to do the learning, and to have choices, has to be there. The great hope of these countries is in generations that can have some critical distance in relation to their own country, people who leave and look at Mozambique in a different way.

That they are no longer so greedy to get rich?

They realize that there are other things, that these societies are not happy. It’s a matter of time.

Literature

You won the Camões Award and this year you were part of the jury. What does this prize change in a writer’s career?

In mine, it didn’t change much. But, of course, I was very happy with the award.

Don’t you express interest in bringing the Portuguese-speaking literatures closer together?

Something must change in the very nature of the prize. Of course, it can award an author, but you realize that our linguistic community is more of a utopia than something real. In Brazil, the Camões Award is little known. One of the intentions of the Camões Prize was to arouse curiosity and publicize the work. For example, in the case of this year’s winner, Alberto da Costa e Silva, it is hard to understand why his work is so little known outside Brazil. This fund should allow his work to be contemplated, publishers to publish it, and the writer to travel. At the Camões, the work should be important, not specifically the author. There are prizes that are organized in a more formal and recognized sense, but others are organized so that young people and students get to know the work. When there is a party, all the new people who are committed participate. That’s what a party is, it’s a process, not just a moment.

Is the prize turning its back on those who can really benefit from the knowledge?

I think so, something must change. But it’s also laziness of ours. Writers must fight more; we can’t abdicate and say, “It’s them”. We are in a strange position, we let the initiatives come from those we say bad things about, from politicians, etc. We must occupy that space.

Do you agree that Lusophony is built more on economic interests than cultural interests and is very much centered on Portugal?

I think there must be a learning process. This project either belongs to everyone or we will have Camões Institutes as institutes of Portugal. There needs to be a Lusophone institution supported by everyone. Why are Portugal, Brazil, and Africa on the Camões jury together? It is not fair. But the truth is that the African countries have never stepped forward to say they also wanted to participate. What does it cost Angola and Mozambique to participate? They are just in a position of complaining. It worries me that Mozambique has a less ambivalent position and less of a complaint. Even in relation to the language. After all these years, is the Portuguese language still seen as the language of others? Either it is assumed, and we are going to treat it as our own, or we cannot ask the Portuguese to act in relation to the language as if it were their own.

The English language is also gaining ground in Mozambique…

Yes, but it’s a bit of a ghost. At the time of independence only 4.5% of Mozambicans spoke Portuguese; today, in urban centers, 40% speak it as their mother tongue.

And the other 20 languages, how are they taken care of?

It is a bit hypocritical, publicly everybody makes a big speech about the indigenous languages, but that implies work and funding, and nothing is happening.

Because they are more orally related languages?

I think it’s mostly a big laziness. As always, you are waiting for the world to come and solve it, if there are no funds… there are no priorities.

What next African could win the Camões Prize?

Among others, Agualusa, Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa, João Paulo Borges Coelho or Ondjaki.

The coming ones

How do you justify not having more new voices?

The war in Mozambique helped destroy the connection to the school, which was already so fragile, and people only had contact with the Portuguese language through books. There was a generation that was sacrificed in its relationship with reading and books. In the cities perhaps not so much. Now values are resurfacing, and it’s curious that Mozambique is taking back the kind of nature more linked to poetry - like Angola, more linked to prose - and there are many promising young people in the field of poetry. Writers are born from other writers; ideas are born where there are ideas. I remember the generation of Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa, they frequented the esplanade of Charrua, Goa, the beer gardens, debates, gatherings in Maputo, the Scala café, where Rui Knopfli and Craveirinha would meet, that doesn’t exist now.

Contagion spaces where one starts to discuss, watch movies, and read books.

Yes, and since there are no such spaces, young people are helpless. There isn’t a week that one doesn’t come to me with a piece of paper, “Hey Mia Couto, check this out!” In our family we had the idea of creating a foundation named after my father - who died last year - he had a publishing house, he wanted to make writers, and he worked a lot with young people. It has now been approved by the Council of Ministers and I have put part of the prize money so that there is a way to take in these young people, writing workshops and so on. There are people who create working groups, and reading clubs, and there is a great willingness of people who love books to do things, even if you don’t know how.

You are currently writing a new novel…

Yes, about Gungunhama but in the meantime I’ve been run over by a book of poetry. It’s systematic, whenever I’m doing a prose book, I only get poetry.

It’s that ‘poet who tells stories that sometimes just gets poetry.

Poetry says “Look, you’re not going anywhere”. But it works, with that emanation of poetry the story I want to see is clean.

Books by Mia Couto, excerpt from Ivone Ralha's infographic

Books by Mia Couto, excerpt from Ivone Ralha's infographic

You seem to have some resistance to the raw, realistic narrative by composing a whole literary idiolect. In The Lioness’ Confession you tried to soften that stylistic mark, to experiment with other things. Did that end up locking you into a certain style?

I felt very suffocated, suddenly it seemed like there was only one dimension, funny, and beautiful, that I didn’t feel like being a prisoner of. I don’t want to do a stylistic exercise, I want to tell a story, and that story asked for that. I want to surprise myself. I’m never going to do something purely realistic, that’s not my style.

It is impossible to report reality without transforming it, but by covering it up with these other ways of saying things, sometimes we seem to lose the violence of the situation itself, don’t you agree?

In this, in fact, I am Mozambican, we don’t speak directly, we can’t say no, and we go around in circles, in concentric discourses, until we get somewhere. The distance of the war might help me, but it was so cruel that, to talk about it, the way I had been taught, I had to pretend I hadn’t learned it, I needed to maintain a certain metaphorical elegance to preserve my poetic side in the face of something so cruel. There will be stories that call for saying things pure and hard as they are. But I have a hard time, now writing Gungunhana I am confronted again with things that were very violent. I have a very difficult relationship with violence. When I volunteered for Frelimo, luckily there were those who didn’t have to deal directly with violence, otherwise, I don’t know how I would do it.

In your life do you give up easily in an argument?

I’m not interested in being right, I don’t feel like that kind of power, to make a point, to pound the table. If I get into an argument, it’s the Chinese way, simply to suggest that there may be another way of looking at things.

Consensus doesn’t always make sense either.

I withdraw, there is a wisdom of avoiding confrontation that has nothing to do with a lack of courage.

Don’t you like the immediate?

No, if we put ourselves in the territory of winning, we’re going to arouse in the other huge appetites in a life where you’ve almost always lost, and people cling to those little triumphs. If we can take the issue out of the territory of dispute it’s easier to convince people that there are other ways of looking at it. I get along well with this way of waging war. The Chinese proverb “the general who won the war without doing any battles” is a motto of my life.

In Maputo or Luanda, it is easy to “stop seeing” and become brutalized by the fact that images of social inequalities are trivialized.

How to see and respond to this is one of the big questions in these territories. For example, I made an intervention in a school, and the issue of transporting workers in open-box vans as if they were cattle, their danger, and so on came up. But people, quickly and surely, think that this is the way it is and that it should continue to be. But my speech was repeated and now people look at it differently.

How do you see the “luandization” of Maputo: an expensive city, extremely classicist, with demarcated territories for whites, with insecurities and all those things of a big capitalist city?

For me, it is almost funereal, although I am not much given to nostalgia. But I also understand that it’s hard to escape because this is the model, I don’t know if we have a great strength to do anything else. I am confused about the lack of civil resistance that would at least clash with the ease with which the city of Maputo is taken.

It certainly doesn’t come from the NGOs.

The NGOs are always around women’s rights and political issues, and the issues of urban space, and heritage, are almost non-existent.

How do you see the Angolan reality?

I see it with some concern because I realize that a certain Mozambican elite looks to Angola as a model from the point of view of behavior, economies, management of society, and the fashion side. Angolans spend their vacations in Mozambique and come to get their girlfriends, there is a certain fascination. Of course, Angola is not only this but there are also many Angolas.

Angolan literature has documented the country’s history, do you follow it?

My concern is to read good books. Angola at the same time is a very curious country for us because it has something we never had: a more refined degree of urbanization, much more consolidated and older. As literature is a phenomenon of the city, Angola has in fact a more sedimented literature than ours, it has several generations, and it is the result of Creole societies. It’s an experience I’d like to visit in Angola.

What about orality?

The phenomenon of Portuguese being the main language interests me, as do the various social traits that manage language, and how they make it plastic.

The Violence

In recent years there have been situations of violence in various contexts. The suburban kids who came to the streets to demonstrate, there were riots. Now this return of the ghost of war. Mozambicans seem to be very passive and shy people, but then there is a certain culture of violence, do you agree?

We can explain it this way: there is an ancient wisdom of societies that had no State, nor mediating institutions for violence. It was solved through families, traditional chiefs, etc. When we got to Independence, many of the communities were still like this, the colonial state was very fragile, only located in the cities. In the post-independence period, it also remained fragile, there was no time, there was the war. The mentality is “I’m not going to expose myself, nor am I going to create a conflict with my neighbor if I’m not sure I’m going to win.” In Europe it’s easy: I have a problem, I go to the police, I believe there is a court, a mediating force. Not here, the person does not expose his opinion, and he will not risk it individually, he only speaks when he can shout or when you are in a majority. That’s the explosion that happens.

The weight of the gregarious society, the individual by himself doesn’t have much value.

The individual is made to negotiate, to enter a consensus. The Mozambicans receive well, they can’t say no, something very oriental. How is it that these same people, so cordial, went to war with a million dead? But it happens, not when it is a drop, but when it is a wave, drop added to drop.

And now with the imminence of something that can destroy everyday life, how do people feel, do they move away feeling that it is a localized thing?

First fear: another war is unacceptable. It is hard to imagine, those who have lived through 16 years of war never want war again. The great force that unites Mozambicans is precisely “we don’t want war”.

One is still afraid to utter the word war. In the floods of 2000, there were people jumping off the roofs in the rescue teams, afraid of the South African helicopters, still with the memory of the war.

A ridiculous situation is happening, at a certain point Renamo and Frelimo are put on the same level, sit down, and talk. That must be asked of Renamo, a political party that has weapons.

Against the blackmail of force, is there no political will via the diplomatic route?

There is some ambivalence. I don’t blame the government, because I think that if it were governing, it would not accept this blackmail of force. The first thing is that Renamo has to convince itself to be a political party. If they are asked to give up their weapons, and they don’t, then it makes sense to use force to take those people away from the path of violence. I myself am divided; in the negotiations, Frelimo was making concessions, and I don’t think that we can continue to give in on only one side, especially because now Renamo’s discourse is that, in the name of the de-particitarization of the state and of the armed forces, they want a partisanization in half. And I as a citizen also want to be consulted.

Mia Couto, photo by José Eduardo Agualusa Can’t it be a warning for the promiscuity between state and party to end, the demand for democratization?

Mia Couto, photo by José Eduardo Agualusa Can’t it be a warning for the promiscuity between state and party to end, the demand for democratization?

Yes, but let them do it differently, the whole argument is moot. Renamo has a seat in parliament. It’s a schizophrenic thing: attacks are happening, people are dying, and the guys are sitting around discussing the budget law or whatever as if it were in another country. So, you can accuse this government of a lot of things, but not of a lack of tolerance. And this being intolerable.

And isn’t the economic factor, someone feeling outside of the “event” one of the reasons for the Renamo blackmail? Why is it that in the years when people were living in extreme poverty, nothing happened, and now, as soon as the economy grows, these conflicts come up?

I think it has more to do with Dlakhama realizing that this is the last time he can run, it is a personal process. I believe that in Renamo itself there are people who also disagree with this path.

Democracy and participation

Despite this, in Mozambique, there have been some steps towards democratization, new parties, etc.

Yes, and the attitude of the citizen who has lost the fear of speaking out and giving his face. The risk of someone who comes out as a citizen, I am here, and I say what I have to say, is very recent. It’s a breakthrough, and it’s causing fear. But it’s that or 2010 with young people breaking everything. That demonstration phase served as a big warning, and then things started happening in the world.

It was an achievement, the young people were outraged, and there was backlash from the government…

Yes. A short time ago also, a demonstration of 20,000 people, with elegance, they organized themselves and showed a great degree of civility. Until then a manifestation meant breaking everything, and this was a great example.

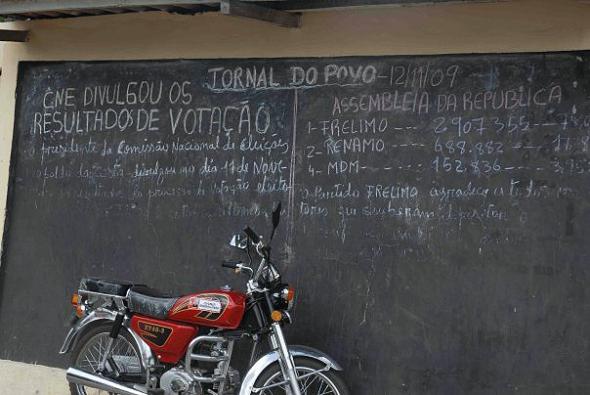

People's Newspaper, photo by Marta Lança

People's Newspaper, photo by Marta Lança

In Luanda, the demonstrations are repressed with arrests and police repression. In Mozambique, it is milder?

From this point of view, I am not ashamed of my country. There is a civilized attitude of the government that accepts. Obviously, there is intimidation, but it is done in a framework that is common today everywhere.

The times of militancy

And then you go to Maputo at 16 to study, and a year later you go underground.

In 1973 I started to have some connections with Frelimo, doing some work in the student movement that I had joined. In 1974 I was formally in Frelimo.

You experienced Independence at the age of 20. Was it a great utopia?

It was the great dream of my life. Even when Frelimo asked me to drop out of medical school, and at that time I really wanted to be a doctor, a psychiatrist…

It was not compatible, it was not the time to study, and there were no conditions?

Because it was thought that there were few young people capable of infiltrating the Portuguese media, that is, extreme right-wing Portuguese. And that took up all my time. The idea was that I would stay one year, but I stayed twelve. It was a very happy time, of great generosity, we were all very committed to a new country, a new world, and a new man. The main mistakes of that time were due to great naivety, and a simplification of the world. Things are more complex.

Didn’t you feel limited?

Not at first, when there were doubts, the argument of the war suspended those questions, I was involved in something bigger. In ‘85 I thought “I no longer believe”, and I had a great urge to leave.

Did the figure of Samora Machel captivate you?

At that very moment, I realized some big mistakes he made. I was the director of a newspaper, and in that capacity, we attended the Central Committee meetings. It was his way of involving us in what he called the “Common Thought,” which I didn’t realize was the only thought. But there was a certain trust, we were involved in the process. There were some very big and violent things, yes. My friend Carlos Cardoso was arrested on Samora’s orders. I would have been arrested if it wasn’t for poetry. They called me and said “Ah, he’s a poet,” as if it were a disease. Samora had a vision, a dedication to others, and a sensitivity that made him be himself, he wasn’t self-centered, he wanted to know about everyone.

And the press that he ran at the time was the right arm of the single thought?

The right and the left.

Samora was aware of the value of communication, he valued the image of people. In the interest of creating national unity?

Yes, he had the notion that it was necessary to build a nation, and this was born out of a narrative, via radio and the press. The first thing he thought of was the news organizations, the journalists if there were any means. He was the first to know everything, where they were going to sleep, etc. He was great, he would come and visit us to see if we had eaten and if we were okay.

Only in the cities, or were there delegations in the provinces?

There was a concern to decentralize, and popular correspondence networks were created. They were very humble people. The first news that reached the Information Agency was impressive, we distributed bicycles to come and deliver the news. The idea was for the country to recognize itself in its differences.

The case of Carlos Cardoso

Carlos Cardoso was already persecuted at that time, and arrested by Samora?

He was arrested on the highest charge of Sabotage to the Popular State. The man could disappear, and it was thanks to a group of colleagues that we gathered evidence that he had not done what was thought. But Samora would talk to him privately and they liked each other. He was punctual. Cardoso’s report contradicted the official version of what the Army had done in a military operation. Cardoso was several people who had this Turkish, Swedish, and Norwegian belief.

He was assassinated in 2000. He had a persistence in the fight for truth and justice. How was it?

He would show up at friends’ houses from house to house, knowing that he was already being persecuted. When we went through the files he was going through, his pockets and drawers, we discovered 12 reasons why he was murdered. He was an incredible person; he had a perfect notion of what he was going to be in the next reincarnation.

What is there to preserve from Cardoso’s lesson?

His name is alive, and among some sectors, they think that intervention journalism is the right way. But I think there was a big backlash. What he did was unique, pointing out names, and presenting evidence.

Son of the Earth

How is Beira doing?

It struggles not to recognize itself as dead. Beira was a port that served the hinterland economies through its corridor, its raison d’être being Zimbabwe. Beira has fallen into decay, and until Zimbabwe rises again from the ashes… One possibility would be to serve as an outlet for the coal that is being discovered on land, maintaining its vocation as an exit line. On the other hand, coal was also a rosy story that did not end well.

Beira, Annie Coelho

Beira, Annie Coelho

You notice a certain splendor of yesteryear that contrasts with the decadence. Do you still have connections or family there?

I have a cousin and friends. Because I am a local son, in Beira they always ask me to launch my books there first. I feel this obligation. My brothers and I got together to rehabilitate the elementary school where we studied. We gave books to the secondary school. That town gave us a lot, I was very happy there. Despite the difficult period when I started to understand the world, it was in Beira that I awakened to this consciousness.

What do you miss the most?

The vacations in the Rovuma mountains, near Zimbabwe, that was the almost absolute absence of fear. We stayed for a month, during long vacations, and camped in those mountains. There were no cell phones, and the parents didn’t know anything about anyone, but it didn’t cross their minds that anything could happen. That world is over now.

Did you have contact with the Grande Hotel da Beira, which collapsed long before independence?

I have a very vague recollection, but I never saw it alive. And I even lived close to that neighborhood. When my father had a problem he would change neighborhoods, if he had a bigger problem, he would change cities.

Article published in Portuguese in Rede Angola 2014.