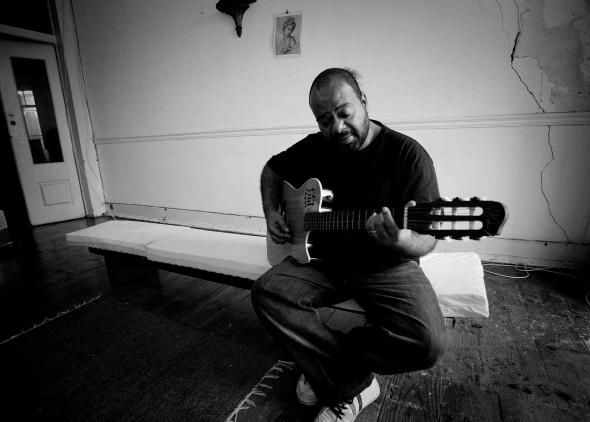

“What I do best is what is most deeply rooted in us” - Paulo Flores

Paulo Flores is a musician, singer and composer. In terms of music in Angola, his voice is unmistakable. His career spans 20 years, he has made 11 records, he has placed his stamp on Angolan music, and he has renovated Angolan culture. His music pays tribute to his homeland, his lyrics put him in the vanguard. His last work is the trilogy “ExCombatentes” (Veterans). The three parts (“Viagem” (Journey), “Sembas” (Semba Music) ande “Ilhas” (Islands) is nothing short of a virtuoso display of talent.

You are missing some Flash content that should appear here! Perhaps your browser cannot display it, or maybe it did not initialize correctly.

foto de José Fernandes

foto de José Fernandes

Where does the music in your life stem from?

I first came into contact with music when I was a child. My father was a deejay, and he had a collection of music from all over the world. Then came the Tubarões, Paulino Vieira, Martinho da Vila, and they all stayed at the house. I have a vide cassette which shows me in the midst of all of them strumming a guitar which is really a bottle, and I also sang over the records. My grandfather on my mother’s side was from Trás-os-Montes in the north of Portugal, and he played the Portuguese guitar. My grandmother from Benguela played the piano (and she spoke French).

Why didn’t you go for a traditional type of music? Didn’t you experiment with rock or pop when you were growing up?

When I was 15, I started to play with Eduardo Paim and Ruca Van-Dunnem. My first album was “Kapuete Kamundanda” (1988), all original music, and it had a lot to do with what nowadays is called kizomba. We began by copying Zouk, with things like ‘Cherry’, and ‘Garina’. I was living in Lisbon, my father (Cabé) went there in 1986 and had Angolan discos: the Kudissanga, the Kandando. So there I was, on the Angolan circuit. But I was back in Luanda on holiday every year and I always kept the contact going. My vision was one of nostalgia, longing, not wanting to be separated (my family spoke about this a great deal). So my first themes were very much in this semba spirit.

Who taught you how to play?

I’ve had no training. Musicians played with me and showed me chords. It was later, in Angola, that I came to understand semba, with Carlitos Vieira Dias, Moreira Filho helping me understand it. In vocal terms, I started by imitating – Bonga, Waldemar, Mukenga. On the first record, every track had its style; everything was in the air because I didn’t know what my sound was. And it took some time before I got there.

How do you account for the fact that your success came straight away?

I got on with making records, and before I knew it, I was on stage. People liked my music from the very first record, so there was never any time to think about things. I remember that I didn’t want to do a show in the Aula Magna. That was one of the first, and I was 16 at the time. I arrived late for the sound check, I was going through a lot of heart-searching and I really couldn’t stand my own voice (in fact I thought it was horrible on the first three records). Nothing was planned. The second record followed a year later. There were eight pieces of music of mine that were going the rounds of the dicos. “Tulucutu” had All Star tennis shoes. In Cape Verde they called them Tulucutu and opened a bar with that name. “Cherry” is still a success in all Portuguese-speaking countries in Africa.

Isn’t one of the reasons for this that your music struck a chord with people at difficult times, at moments of great nostalgia in Angola?

It may have acted as therapy, yes, but fundamentally there was just a big hole where Angolan music should have been. We had Bonga, Waldemar, Tetalando, but overall only 3 records with Angolan music in the last five years. Also, I think my music was a new way of approaching language. Things were seen in simple terms, and I tried to give value to day-to-day street cred. This came over as something pretty fresh.

fotografia de Iuri AlbarrãDo you always write your own lyrics?

fotografia de Iuri AlbarrãDo you always write your own lyrics?

Yes. I sing the tunes with words, and the lyrics flow from the music. I’ve already worked with poets such as Carlos Ferreira (Cassé) and Albano Cardoso.

Was it easy to get a group together?

My father had a disco. África Tentação played there and at the time it was the only group in Portugal. The band Kandando played back up. Then I made a record with Eduardo Paim on Radio Nacional and from there on I started to put groups together. I found Manito, Carlitos, Simmons, Manecas Costa, Boto Trindade - who is one of the first (he comes from the time of Urbano de Castro), and this was the band I’ve worked with for three years. Before that I played with the Banda Maravilha. And I invite musicians from Brazil, from Portugal, and so on.

You’re a musician who plays semba. Haven’t you felt that you could play other styles?

I like singing semba but that’s not all. I do a number of gigs during the year, one that’s more to do with the music, then one that has the big hits, then another with more semba. I don’t feel the need to sing or compose that kind of music for everybody. By it suits me. I can bring something new to it, in the words, the lyrics, the way Portuguese is used, the way the themes are handled. It was an important contribution. My feeling is that what I do best is what is most deeply rooted in us. That’s where I have a chance. But where creativity is concerned, I look for other options. I don’t feel constrained to do just what people expect of me. There are other routes, and we cannot be guided just by criticism or trends. To create something that makes sense, you’ve got to be prepared for what comes.

Your sembas are a kind of X-ray of Luanda urban life. There is a kind of nobility you bring to ordinary life. There are people who have no say in things and you give them a voice.

This is a conviction I have that comes in a way from the despair of seeing people living day in day out in surreal, subhuman conditions. This exists all over the world, but what called my attention most in Angola was people’s strength, and the true humility that comes from what is called the arrogant banga of the Angolan people. I see a great deal of this humility in the people who have always been here and the way they can keep their heads up moves me tremendously. I have always raised my voice against this kind of thing, but when you see the way people carry on in their lives and keep their identity so strong, that is what inspires me.

There is something in your characters that you couldn’t say in any other way. You’re also creating identity as you give them a name and bring them into the limelight.

When I begin to write a piece of music, I never know where it will take me. There are many cases where I take a long time to understand what I am writing. These are chronicles. They’re portraits of our times. I believe that in a few years time, someone will find things written down in my music that allow them to see more clearly what things were like in our times. I try to put other readings into my work, I look in a more poetic way.

You don’t just describe the reality of life in Angola. You talk of Palestine in one piece and of Lisbon in another.

“Xé Povo” (John Bull) already has a vision of the world. But this record, “Ex-Combatentes”, well, it has a wider compass. I composed it in the Avenida dos Combatentes (in Luanda) and it concerns the vision of an Angolan or an African about today’s world. I create from the everyday world, from the dust, the trade, the shambles, the parabolics, the information I get. We have access to everything. We are absorbed by all the mutations, Barack Obama, and so on. We are split between the laid-back pace of the now dead 20th century, with all the time and space it gave us, and this crazy, schizophrenic rhythm of the 21st.

From an overview of Angolan music, it looks as if almost all the music is about Angola. There’s a lot of need to look in and say what’s there.

People cannot write about things they do not know. But there’s a big clash between the Angolans who have been abroad and those who have always been here. It seems as if those who stayed here are very quick, but they never had all the information, and those who were “over there” have some information but they move around here as if to say “I’m the one who knows it all” and in the end they don’t put in as much as they could.

fotografia de Iuri Albarrã

fotografia de Iuri Albarrã

There are flavours and sounds in what you do that are reminiscent of Cape Verde.

It’s part of my upbringing. What I took in. I went around a lot with people from Cape Verde when I was in Lisbon, in B.Leza with Tito, Bana, Ildo Lobo, Manecas da Guiné,. All these people were part of my music. It’s a question of instinct. I feel as much a Cape Verdian or a Brazilian or at times a Portuguese. I love those other cultures that are part of who I am.

What do you think of today’s Angolan music?

I’ve taken part in the Kuduro with Dog Murras, in Rap with Mck, and Nástio Mosquito worked with me. There are many new languages in Angola. Kuduro is the most representative, and in some ways the most creative. At least it is at the level of thought which is in many cases not understandable in language, but if you are able to understand what is really being said, there are things here far in advance of other types of song based on love, or spells or a woman has done something wrong.

And what do you think about the fact that Kuduro has come in for such a lot of criticism by some intellectuals?

I think polemical issues are never a bad thing, you know, people are scandalised, revolted. Let everyone join in and use their art and their revolt, so there are have more people breaking new ground in the search for a new creativity. These days, not so much value is given to things, the rhythm is not the same, so it’s logical that music should be different. We used to get out of work and go to the island for lunch but we can’t do that now, we can’t see the sunset nor the sea in the same way. This is mirrored in creativity. I don’t think it’s strange that older people don’t understand these new languages, or that they only go for what they understand.

How do you see your career at this stage? Are you at the end of a cycle?

It’s time for a shake-up. I feel really free in what I do and I want to feel alive, creative. I’ve reached this 20-year career landmark and what I’ve done is recognised and respected. Now my search is very personal, something that I want to complete with my artistic work.

fotografia de Iuri AlbarrãWhat is your opinion of the path that Angola is taking?

fotografia de Iuri AlbarrãWhat is your opinion of the path that Angola is taking?

We are living in an age where in the world over there seems to be only one thing that will happen and that is complete chaos so that everything can emerge again. In Angola, everything is in our hands, everything we do here will be decisive for the next 15 to 20 years. What choices are we going to make? There are signs of a concern to make sure things are done well. But there are also choices being made that leave me perplexed. Personally I want to play my part, with my words, my music, my thoughts. I want to carry on living here and I would like my children to get a better education, with more quality and information available for everybody. Most of the possibilities we have depend on education.

What do you see as the most positive aspects of the challenges facing the country?

Fundamentally the optimism that people show. It gives me a feeling of confidence, this predisposition of people, this way of looking at life and seeing things change.

What are the areas that need urgent improvement to bring about a more balanced society?

In my view, it’s all about the distribution of income, domestic production, agriculture, education and culture. Wee need to stop thinking so much about oil and begin to produce more. We have to take care of our human resources and provide more possibilities for people to know more. They have to know English, be aware of politics, understand the Internet. This is what we need to create a more sustainable growth.

In practice, what does it mean to be Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations in Angola?

I honestly don’t know yet how far I can go with what I do. I would like to do things here. We have plans with the Ministry of Education and private enterprise for May, June and July. We have had discussions already. There was a show last year, on 8 March. Instead of buying a ticket, you took away a book. I’ve been on a goodwill mission to a number of provinces: Huambo, Malange, Benguela. I’d like to do things in education and culture. I’ve done something already with the company Catoca and the proceeds went to the Gaiato houses. This is also good for the institutions because it gets them better known. My first idea was to put up an arts and crafts school, where people could get together. But now I’m rethinking everything.

Do you think music can fight against this globalisation current?

Trying to be genuine is an illusion because there’s no chance of being creative without being influenced. I see myself in many aspects of my life as Angolan. But what does that mean? Only belief and willpower give us true creativity, because our feelings are being expressed.

What are your biggest defects?

Sometimes I’m intolerable when I wake up, because I may be depressed. I’m no longer insecure, but I used to be. Now I think more for myself. I don’t think so much about what people are going to think or like. I’m sometime lazy, not like having to do things with lots of lights on me, but I’m a public figure so some things I have to put up with. It’s just that at those times I am not me, I’m only a part of the music that is coming from the orchard, from my friends. Today, though, it seems to be easier to make a living as a public figure than as from the arts. But being a public figure is a cloak; it’s not where I really live.

And what about you and money?

Me and money? That’s very simple. When I have it, I spend it, when I don’t, I save it. What I like most is spending money on the people I like. I don’t think much about the future. There’s no point in this profession.

Luanda, January 2009, in AUSTRAL nº 73, article kindely provided by TAAG - Linhas Aéreas de Angola