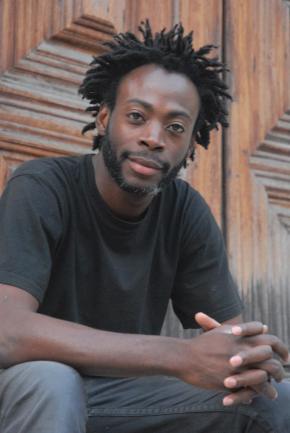

Carlos Paca “Theatre and its instant feedback is the real deal”

Photos by Otávio Raposo

In an African Lisbon of al fresco cafes at the end of the afternoon in the beggining of 2009’s summer, Carlos Paca, an Angolan actor, an active, young 31-year-old talks with a passionate voice, charged with experience and the promise of the future. He speaks of his disillusion with the discrimination for the black actor in the Portuguese market. He speaks of his experiences.

What made you leave Angola?

The main reason for leaving the country was my fear of being conscripted. I had already lived in the U.S.A., in Switzerland, in South Africa. I went to Angola in 1992 as it happened, and I fled in 1998. I was 18 years old then.

What ties you to Angola today?

I’m a regular. I visit frequently, a couple of times a year. All my family is there, over here I only have one sister and a nephew.

How did you feel the first time you emigrated?

I felt at home at once, I never felt culture shock or that things were very different. I come from a family that’s used to travelling to Brazil and Portugal. I was always leaving friends and girlfriends behind. But New York was such a leap it really turned my head.

If you’re always on the move, you become a rolling stone…

Not really. I feel a certain coolness when it comes to making new friends. I get close to people, but when we’re apart, we’re apart. I can go for a long time without speaking to my brother and then pick up again as if no time has passed at all.

Why did you go to New York?

My mother died in ’88, and my brother had always dreamed of America. So, I went with him to study in High School. I worked in a pizzeria 8 hours a day. I earned 300 dollars a week, it was enough to get by.

How did you discover that you liked acting?

I joined several drama groups at school. I didn’t like studying, but I was still a good student. Acting was a way to escape. I just wanted to have fun. In Angola we have estigas – ribbers and no one could put up with me. Then, I learned in the USA that ribbing is stand-up comedy. I’m a natural comedian.

When did you turn professional?

When did you turn professional?

When I got to Lisbon, I enrolled in the TV & Cinema Academy. When I was giving up all hope of becoming an actor in Portugal, in 2004 I starred in a professional production of Laranja Azul, by Joe Penhall, produced by Natália Luíza. I have a brother with psychological problems, I’m the only one who understands him. The casting had been done and they couldn’t find anyone to play the part of this character. I had had a lot of experience dealing with my brother (I knew the medication he needed and monitored him constantly), so the character was easy for me to portray. It was the play I most liked acting in, I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. We rehearsed at Júlio de Matos.

How do you feel about theatre and television?

I feel that in order to have lived, you have to have performed theatre. Becoming an orphan was a tremendous shock: when my mother passed away, I cried non-stop, but later with my father I found I couldn’t cry, my heart had been seared. The theatre helped me to work through my emotions and to get over things I hadn’t had – I couldn’t remember the last time I’d celebrated Christmas. The theatre gave me a sense of community, family, and warmth. Alas, that doesn’t pay the rent. That’s why I have to get involved in television and cinema. But theatre and its instant feedback is the real deal. On television, I feel very false, it moves very fast, there’s no time for a person to settle in. And today everything revolves around image, and business. We are still badly treated.

What issues do you feel black actors face when they are hired, what kind of roles do they do? Are there limits imposed on purely racial grounds?

Yes, there are. What is most bewildering is that we are in Portugal, a country whose population in the 15th Century was a fifth black. We have been living with each other for 500 years. The people behind the art scene in Portugal today used to be our old teachers. I can’t understand why we are still perceived as typecast actors, only playing specific parts written for blacks. Many times I have been told, “there are no roles for black actors”, but what is a role for a black man? I really can’t understand it.

Can you give us some examples?

You can only get work if it’s about racism or ghettos. We end up getting saddled with this kind of subject matter.

But couldn’t you become important role models?

These days I have given up on the Portuguese market, because it won’t do anything for us. Take the famous actors who have already gone back to Africa. Ângelo Torres, and Daniel Martinho, are so well known, yet they still need to go to castings. (For example, in the series Equador, the only S. Tome actor, winner of an important French award, had to do a stupid role, he just held the reins of the main character’s horse.) Looking at their experience, I can see that I don’t stand a chance here.

Given that there is such familiarity between Portugal and Africa, why is this question not debated more?

We, in Angola, lived with the Portuguese; here we live among them. They invite us to the table, but don’t us offer any food.

There was some controversy during the contracting and the filming of the series Equador, when some of the actors (one in particular) made a protest. What was it all about?

There was some controversy during the contracting and the filming of the series Equador, when some of the actors (one in particular) made a protest. What was it all about?

We were finishing up filming Equador in Brazil. The Portuguese actors were discussing the next project and casting the characters, but not a single black actor was chosen for the project. There were no round-table discussions with us, to find out about our backgrounds, to hear our point of view. That’s because they know it all, we just have to sit back and listen. There was a choreography that I wanted to invite Petchu from Kilandukilo to do, but no, they invited an Italian choreographer instead. There were things we wanted to share. On the whole, black actors are considered inexperienced, because they have not had a lot of television parts: you know the acting techniques, but because you don’t perform enough, you’re seen as inexperienced. But if they don’t give us a chance, it’s impossible to get experience. Plus black actors are paid less and are badly treated by the producers. Our diction, our accent is always cited as a factor. The conditions are right for black actors to act in every Portuguese production. After all, today, the Portuguese economy is propped up by Angola’s, they should get smart and start to support us more. At this moment in time, there isn’t a single black actor working on anything. That’s not normal. In other countries, things flow and happen.

How many professionals exist and what roles have they played?

There are around 40. Almost all the parts are either waiters or villains. I’ve just been invited to act in the series Lola, I have to beat up a transvestite. The only black man in the thing, and he’s portrayed assaulting someone. I don’t mind, but they don’t ask me to do even a little bit more, they don’t offer me the part of a character who’s there from start to finish so I can support myself and have work. I don’t want to become a set painter.

What is it like in other countries, like Brazil, for example?

When it comes to being black, they are much more open minded and the struggle for work is taken seriously. They still complain, of course. But the difference is that a black actor in Brazil is a Brazilian, but in Portugal you feel like an immigrant - and how! If we are excluded from all sectors of society, what can we do? But there’s the other side of the coin: what do black actors do to counteract this situation?

What sort of things do you do to confront this mentality?

Together with Daniel Martinho, Ângelo Torres and Miguel Sermão , we plan to create an association, become partners, and start to produce our own projects. We have an agency, the Box, a mix of white and black actors and an agent, Pedro Figueiredo. Box challenges the market to force it to pay an equal amount to each actor. We want to bring more actresses to the party, there are very few women around. The market revolves around money and image. If we want to compete in this market we have to play by their rules.

But are people generally aware of this discrimation?

Yes.

Portugal, New York, Brazil, India: what aesthetics and techniques have influenced you the most?

The USA is light years ahead, their theatre is very good, as is British theatre. It’s more commercial and well established. If you go to Broadway and go to the theatre, you become ensnared. In India I realised how arrogant the Europeans are, the Indians are streets ahead when it comes to the cinema industry. A Bollywood actor has many things going for him: he sings, dances, acts, he’s not a product, but a real star, and he earns a lot of money. Europe has to stop having double standards for the rest of the world. There’s a lot we can offer. My focus in on Angola now and getting my productions off the ground.

What is it like living in Lisbon, do you think there is a real meeting of cultures?

There are many cultures in Lisbon, people from all over. Today I was in a Nollwood videoclub, on Almirante Reis, with people from Ghana, Namibia, etc. People shut themselves up in their communities, in their comfort zone, and don’t speak out. Slowly some things are starting up. We have to make things happen. And take advantage of the best of music, dance, theatre and cinema.

What about taking culture to the suburbs?

What about taking culture to the suburbs?

The difference between myself and a second generation immigrant is that he’ll be the son of a domestic cleaner and a construction worker. He’ll have been born on the razor’s edge, with an identity crisis, he’ll have no roots. He’ll have a different outlook. For him, writing a novel is an opportunity, so that’s why he’ll accept any old cachet.

Since you arrived, from 1998 to today, what has changed?

A lot has changed. The Portuguese are nicer, they smile more. It’s down to Brazilian and African immigration. There are many multicultural couples, especially white women marrying black men. Despite this, though, the ideal of beauty is still very westernised. In India, the big Indian stars are almost all white, they use light foundation. We have to recognise and value diversity, we are losing so much because of this short-sighted approach.

Despite black people’s self-stigmatisation, Angolans have a different attitude, they are proud.

Angola is very un-African. If you wear African clothes, you’ll be called a Zairean. And in other Portuguese-speaking nations it’s the same thing, Cape Verde is culturally very European. Angolans are arrogant, the arrogance is there, even if it’s not always recognised.

Are you like this too?

Yes, I can’t not be. I have felt multicultural in the past, but today I feel more Angolan than before. I started to learn Kimbundo to play my character in Equador.

The fact that Angola is an emerging economy, and with the boom how has this affected the perception of Angolan immigration over here?

If there is work in Angola, people are looking for Angolans. Suddenly, Angolans are like Americans in Portugal, they are perceived differently.

Do you think of doing something in Angola?

There’s no place for me here. To me, Europe is just a door to other destinations. I am not going to stay here until I’m 40, waiting for an opportunity to arise. I’ve already shown that I’m good. We’re going to make a bridge with Angola, and with our experience we will change things. I’m an actor, scriptwriter, director, I’m very busy with the TV networks. There is no future for an African actor in Portugal unless they work through Angola.

A product of globalisation

A product of globalisation

This Angolan actor isn’t short on training. He’s influenced by many things, he’s a product of globalisation. His long list of achievements include lending technical input to the TV and Cinema Acting Workshop run with Bill Josh in South Africa in 1994. Here he also performed comedy with Linda Shin. In 1998, he headed to New York to be coached in acting by Joel Perez. At the start of the millenium, he went to Lisbon to train with the TV, Theatre & Cinema Academy (Art’6). In 2003, he flew to Brazil, this time to learn TV and Cinema Techniques for Professional Actors from actors Maurício Matar and Wolf Maya, of TV Globo.

He receives an Angola Prestígio award; in theatre he still deals all the cards. We saw him perform in “Lisboa Invisível”, a play produced by Teatro Meridional, which showed the day to day reality of African immigrants in Lisbon. He acted in “Os Lusíadas, Rumo ao Oriente”, produced by Antonio Pires. He was in Culturalkids (2007), “The Blacks” by Jean Genet, directed by Rogério de Carvalho, in Porto, with an all black African cast. He also acted in “White Man Black Man” by Jaime Rocha, produced by Teatro Aberto (2006), and in “Laranja Azul” by Joe Penhall. Just to name a few.

Cinema and TV parts

2010 - O Grande Kilapy, directed by Zézé Gamboa2008 – Kaminey. Indian film directed by Vishal Bhardwaj for Bollywood (Main character, Cajetan character).

2008 – Equador. Mini-series based on the novel by Miguel Sousa Tavares (Joanino character) for TVI.

2007 – Superfície. A film directed by Rui Xavier. Berlin Festival Jury’s Special Mention. Lisbon Indie Festival Best Photography Award

2007 – Gente Fina. (Main character and writer), Comedy programme on RTP Africa.

2007 – Os Primos. TV programme directed by Nuno Vieira for RTP Africa.

2007 – Sempre em pé. Stand up comedy, TV programme for RTP 2.

2005/2006 - A Revolta dos Pastéis de Nata. Actor and screenplay writer for RTP 2.

2005 – Bocage. Series directed by Fernando Vendrell, David & Golias Productions for RTP 1.

2005 – Tudo que Você Quer Saber Sobre. Series directed by Teresa Guilherme RTP 1 productions.

2004 – Inspector Max. Police series directed by Attilio Riccó, Fielmar productions, (character Dre) para for TVI.

2003/2004 – O Crime não Compensa. Ediberto Lima Productions, SIC.

in AUSTRAL nº 74 article provided by TAAG - Linhas Aéreas de Angola