Notes on Curatorship, Cultural Programming and Coloniality in Portugal

This article examines the impact of contemporary curating and cultural programming in the configuration of critical perspectives on Portugal’s postcolonial identity. It argues that visual creativity is forging a new paradigm in the Portuguese cultural field. In this context, postcolonial discourses are not silenced but, rather, aligned with international agendas in broader cultural initiatives mirroring the transformation of the main Portuguese cities into cosmopolitan, multicultural, and multiethnic enclaves. This situation, however, does not imply that these new visual productions are liberated from the present contradictions deriving from the legacies of colonialism. In addressing this situation, the essay seeks to understand how artistic practices and curatorial conceptions have begun to develop a critical reading of the major questions centered around current debates on coloniality in Portugal.

Introduction

In an interview published in 2014, the Portuguese artist Ângela Ferreira, one of the first voices in claiming an active role for the visual arts in demanding a more critical approach to the continuities of Portugal’s imperial imaginary in the present, pointed out a change in the role of artistic discourses of postcolonial Portuguese society. In the early 1990s, Ferreira was a pioneer in producing installations and site-specific installations challenging the amnesia and nostalgia that she found in the way many Portuguese conceived their own identity and their relationship with the country’s colonial past.

By then, she had opened new paths and confronted an artistic milieu that was reluctant to accept that kind of criticism. Two decades later, after Portuguese cultural and artistic institutions began accepting and even seeking out postcolonial-infused discourses in their programs, Ferreira recognizes a transformation consisting of two main elements: first, the discourses and initiatives critically reflecting upon colonialism and coloniality have become more frequent in a Portuguese context; second, despite this transformation, there still exists a lack of public awareness regarding the continuities of colonial power/knowledge patterns in present-day Portuguese society. In this sense, she states, categorically:

“Se me perguntarem, para mim a situação ainda não está resolvida. Por mais que haja centenas de jovens artistas a trabalhar no suposto pós-colonialismo, o discurso pós-colonial é um discurso falhado, porque não reparou nada a meu ver ainda. Obviamente que há avanços, há pontos de vista mais abrangentes, estamos todos mais abertos à discussão democrática, tolerante, mas se me perguntarem se o cerne das desigualdades está resolvido, a minha resposta é ‘não’.” (Vahia 2014)

Ângela Ferreira, 'For Mozambique' - Model nº 3 for propaganda stand, screen and loudspeaker platform celebrating a post-independence Utopia. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

Ângela Ferreira, 'For Mozambique' - Model nº 3 for propaganda stand, screen and loudspeaker platform celebrating a post-independence Utopia. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

Ferreira’s answer reveals two important outcomes: first, it entails a rupture—a “post”—in relation to a previous moment in which postcolonial concerns were overwhelmingly marginal and invisible within the Portuguese fields of art and culture. Second, the consequences of that rupture, and the results deriving from the proliferation of postcolonial visual approaches to Portuguese reality, remain ambivalent, for, as Ferreira argues, they have not altered the structural matrix of coloniality, which we understand, following Aníbal Quijano (2000), to mean the continuation of a rationality based on colonial expansion under democratic, postcolonial settings. Based on this logic, in Ferreira’s words, the cultural politics of display and production of contemporary art emerge as a dual-purpose tool that can be applied to criticize but also to uncover the coloniality of modern-day Portuguese society.

This implied ambivalence compels us to redefine the effects and affects felt by how art is produced and displayed. If the recent Portuguese artistic panorama substantially differs from the landscape Ferreira found at the beginning of her career, this transformation also demands from us something else aside from merely looking for different answers concerning the weight of the colonial past in the configuration of Portugal’s contemporaneity. It urges us to reformulate our questions in order to tune in to this shifted landscape. The challenge would be, then, to go beyond the surface of a present time in which cultural discourses on Portugal’s postcolonial identity seem to have become part of a common trend, in order to explore the ways in which the production and display of visual creativity address the structural inequalities of Portuguese society deriving from the consequences and continuities of colonialism.1 In that sense, it becomes all the more necessary to evaluate to what extent and in which ways do the displaying and programming of art remain a potential site of cultural intervention. According to Terry Smith (2012: 19), curating is both a practical and logical activity; an unfixed concept concerned with the public character of cultural production inasmuch as with the possibilities of proposing and imagining alternative, more democratic ways of displaying artistic and cultural production. Understanding curating from this expanded perspective, we seek to examine its relevance for addressing the most recent contradictions of the cultural field in postcolonial Portugal.

Portugal has a long-standing and pervasive relationship with colonialism, the consequences of which extend far beyond the (late) formal end of the Portuguese colonial empire. The colonial experience was crucial in determining the shape of post-dictatorial, postcolonial Portugal, with one of its most influential consequences being the impact of migration from a wide variety of locations, but especially from spaces that were colonized by Portugal. These migratory inflows, which began before Portugal joined the European Union in 1986, have radically redefined the social and ethnic fabric of Portuguese society, bringing to the fore broader debates on the consequences of (the silencing of) colonialism, the continuation of exclusionary spatial and social dynamics, and the persistence of racism in open and covert forms, despite the image of Portugal as a modern, cosmopolitan and receptive society. In this sense, Fernando Arenas (2015: 357) argues that a new lexicon aware of issues around ethnic citizenship and migration has emerged in Portugal over the last twenty years, something, he clarifies, that does not imply the disappearance of racism and racial exclusion. On the contrary, new forms of discrimination have surfaced under the umbrella of intercultural citizenship, impelling cultural industries to remain entangled between supporting and rejecting that image. If we live in a time where postcolonial discourses have expanded and become consolidated, there also exists a general awareness of the incapacities of such criticism to address structural issues related to ethnic citizenship.

Several authors have analyzed in detail the contradictions deriving from the legacies of colonialism in contemporary Portugal, and hence we will not delve into those debates exhaustively. The deconstruction of the Lusotropicalist myth about the exceptional character of Portuguese colonialism has been the subject of much scholarship over the past two decades. A consensus exists about the idea that Portugal was never fully decolonized, and that the formal, political gestures that defined the new image of the country were detached from more structural concerns affecting broader segments of the Portuguese population. In Eduardo Lourenço’s well-known formulation,

“A verdade é que a nova classe política—por razões aliás explicáveis—descolonizou exactamente nos mesmos termos em que o antigo regime levara a cabo a sua cruzada colonialista. O país foi posto diante do facto consumado e como tal o recebeu, não só porque tinha a vaga consciência de que não era possível outra solução como supunha—talvez a justo título—que era o preço a pagar pela sua própria libertação.” (2000: 63)

Continuing this line of thought, several voices have attempted to produce a postcolonial perspective on historical events and collective memory (Ramalho and Ribeiro 2002). Boaventura de Sousa Santos’s theorization of the semi-peripheral condition of the country (2002), Margarida Calafate Ribeiro and Ana Paula Ferreira’s focus on analyzing the ghostly presences of the country’s imperial past (2003), and Miguel Vale de Almeida’s interest in drawing the position of Portugal within a broader Atlantic landscape (2000, 2002) can all be understood as paradigmatic in this sense.

Portugal não é um país pequeno. Contar o ''Império'' na Pós-colonialidade, org Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, 2006

Portugal não é um país pequeno. Contar o ''Império'' na Pós-colonialidade, org Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, 2006

The works of Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, Miguel Jerónimo Bandeira, Inocência Mata, Cláudia Castelo, Miguel Cardina, Nuno Domingos and Marta Araújo have continued and expanded upon these debates. From different perspectives, all these authors concur that the formal end of the colonial situation did not put an end to the structural inequalities deriving from Portugal’s colonial experience. It thus follows decolonization must be understood as a crucial yet-unfinished and evolving process, the consequences of which are yet to be seen. As António Tomás states:

“O que se nota hoje em Portugal é uma dificuldade em lidar com o passado colonial. É simultaneamente como se Portugal nunca tivesse colonizado e nunca tivesse descolonizado. Ou é como se a descolonização tivesse tido lugar em África, mas nunca tenha ocorrido em solo português. Talvez porque o que foi madrugador não foi Portugal ter reconhecido a injustiça da escravatura, em 1761, mas ter transformado “colónias” em “províncias ultramarinas” em 1951, na revogação do Ato Colonial. Isso só por si não conta como descolonização, naturalmente. Mas Portugal levou a sério esta farsa. Serviu de justificação para a pressão em descolonizar imposta por organismos internacionais. No discurso da época, Portugal não podia descolonizar porque não tinha colónias. Consequentemente, o Estado Novo não teve de lidar com a descolonização. E tendo havido uma revolução para que Portugal deixasse África, o abandono do império acabou por ocupar o lugar de uma descolonização efetiva.” (2017)

In this article, we suggest that the display of visual creativity has played a central role in the configuration of critical voices against the more normative views of Portuguese postcolonial identity. The production and display of contemporary art have provided Portugal with a space to experiment with more open and critical ways of examining the continuities of colonialism in post-dictatorial, postcolonial Portuguese society. Since the late 1980s, art in Portugal has served as a privileged platform for challenging normative foundations, granting legibility to problems of inequality, discrimination and exclusion, destabilizing consensus, and opening the debate to future, and even utopian, perspectives. Due to its ability to examine the particular and express the subjective—and offer different points of view—art has been used to confront pervasive, if not always evident, power dynamics. Working in the field of imagination, and with greater freedom, Portuguese artists have expanded and counteracted the knowledges and certainties connected with Western models and mechanisms of production and legitimizations of truth. Their research through images or movement have provided a more immediate, communicative, and empathic insight than academic knowledge. Art has emerged as a theoretical tool, magnifying and subverting conservative and colonial conceptions of the world. Understood in this way, art has the ability to potentially deconstruct and challenge the dominant narratives regarding the continuity of the colonial past in present-day Portuguese society.

At the same time, however, the display of art provides a perfect example of the contradictions that define the Portuguese cultural milieu. On the one hand, Portuguese curators and cultural institutions have offered an image that clashes with the celebratory and nostalgic visions of colonialism. On the other hand, curating and cultural programming have become an essential tool for the production of an image of Portugal as a multicultural, modern society that has eschewed the legacy of colonialism. The creation of museums and cultural centers is essential in shaping an image of Portugal as a modern society attempting to overcome the incongruities of both dictatorship and imperialism. At the same time, these spaces contribute to the commodification of postcolonial Portugal as a supposedly multiracial, multicultural (but not racist) creative hub, a process that intensified after the second decade of the twenty-first century as a result of the process of urban and touristic redefinition of many Portuguese cities, most notably Lisbon.2

In engaging with the contradictions of visual display in that particular decade, this article focuses on the potential of curating to provide successful responses to these obstacles. To do so, it attempts to accomplish four main objectives, corresponding (although not being limited to) the main focus of the subsequent sections:

1) understanding how curating has dealt with coloniality in post-dictatorship Portugal; 2) framing the emergence of cultural programming and the impact it has in the display and distribution of artistic discourses;

3) exploring how recent visual and performative practices are offering critical views of the country’s postcolonial identity;

4) finally, evaluating how the display of visual creativity is critically addressing the “cerne das desigualdades” that Ferreira mentions in her interview.

Contemporary Curating and the Legacies of Colonialism in Portugal

The interest in exploring the legacy of imperialism in the Portuguese context through artistic and curatorial expressions can be traced back to at least the 1990s, emerging in tandem with landmark cultural institutions such as Culturgest and the Centro Cultural de Belém, and the transformations within pre-existing institutions such as the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian and the Fundação Serralves.3Culturgest was created in 1993 and was responsible for some of the earlier curatorial projects dealing with issues of coloniality within the Portuguese context, and the introduction of non-European art through the efforts of António Pinto Ribeiro.

Moshekwa langa, installation skins, 'Don’t Mess with Mister In-Between' (1996)

Moshekwa langa, installation skins, 'Don’t Mess with Mister In-Between' (1996)

Exhibitions such as Ruth Rosengarten’s Don’t Mess with Mister In-Between (1996), which provided a sense of urgency in the evaluation of racial dynamics by confronting the situation of post-Apartheid South Africa, also spawned an interest for contemporary African art that was useful in challenging both the Eurocentrism of the Portuguese curatorial scene and the stereotypes vis-à-vis African art that prevailed in the country. The Centro Cultural de Belém also opened in 1993 as a multipurpose cultural platform. Although in its early stages it evidenced a more European-oriented focus, within the last ten years it has also dedicated a space to the exhibition of Portuguese-speaking visual creators concerned with coloniality.4 For its part, the Fundação Gulbenkian, which was founded in 1956, has played a pivotal role in the Portuguese cultural and artistic milieu, funding art exhibitions, research and publication projects. Finally, the Fundação de Serralves opened its doors in Porto in 1989. At various times, and based on different needs and proposals, in these four cases the curatorial program developed during the 1990s drew heavily on making the works of artists from Africa visible, particularly those from Portuguese-speaking nations.

Parallel to this scenario, contemporary art has become a social and touristic attraction, and curating has provided a pivotal tool for the creation of an image of contemporary Portugal as a multicultural, modern society wanting to rid itself of a dictatorial and colonialist past. With more or less successful results, and in heterogeneous ways, during the last decades of the twentieth century curators and art institutions began fostering an awareness of issues relating to Portugal’s colonial past. More recently, this interest also has permeated both individual practices and curatorial programming, generating a renewed interest in the definition of Portuguese identity as embedded within transnational and global fluxes. Given that some episodes of this history have already been widely analyzed, this section offers a brief, and necessarily incomplete, periodization of these curatorial practices concerned with postcolonial issues. Broadly speaking, four phases can be outlined in this process:

1. A first phase, from approximately 1974 to the late 1980s, was dominated by the invisibility, marginality, and social disinterest in artistic reflections of the legacies of Portuguese colonialism, starting from the end of the dictatorship and ranging across the eighties. Although some initiatives surfaced at this point, there was a general lack of interest both in “non-Western art” (as otherwise in any other European context) and in Portugal’s imperial past (as a kind of amnesia). Instead, a strong preference for linking Portuguese artistic contemporaneity with European trends prevailed.

2. A second phase, which generally aligns with the second half of the 1990s and the first years of the Millenium, was dominated by the “multicultural” policies of emerging institutions and cultural events. A central point within this phase was marked in the late 1990s by the commemoration of the “Discovery” of Brazil and the Portuguese “Expansion,” which gave way to an intensive process of cultural branding seeking to give an account of Portugal’s “position in the world” tied to its “glorious” imperial past. Although many of the initiatives arising during that period were celebratory and perpetuated Lusotropicalist visions of Portugal’s centrality to a great degree, some curatorial manifestations such as Isabel Carlos’s Trading Images (1998)—which questioned the idea of overlapping Portuguese and Brazilian art under the excuse of the Centenário—and certainly Ruth Rosengarten’s and Paulo Reis’s Um oceano inteiro para nadar, framed contemporary curating as a contested terrain influenced by but also influencing the ideological debates regarding the political representation of Portuguese postcoloniality.5 Although in the first case, the exhibition was organized around the decisions made by the curator, in the second space was left for hesitations and a more profound dialogue among the two curators. Produced in 1998, Um Oceano inteiro para nadar was organized around the critical exchange between both curators on the ideological difficulties implicit in producing any approximation between the Portuguese and Brazilian contemporary art scenes. It rejected the idea that a simple juxtaposition of the histories of Portuguese and Brazilian art could channel any critical view of the relationship between both territories in such an ideologically charged environment as that of the commemorations. Because of that, both curators articulated an innovative, anti-celebratory approach, showcasing the work of artists who were critical of both the Estado Novo dictatorship and the Portuguese colonial enterprises, including Paula Rego, Nelson Leirner, Ana Vidigal, and Ana Bella Geiger.

3. During the second half of the first decade of the Millenium, the Portuguese art milieu was more strongly shaped by intercultural dialogue and a focus on the processes of “othering” taking place in the country. A growing market interest in artists from Portuguese-speaking African countries was developing, connected to the success of Angolan artists at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and to the first Trienal de Luanda in that same year. Under the curatorship of Fernando Alvim and Simon Njami, the African Pavilion at the 52nd edition of the Venice Biennale showcased the work of a young generation of Angolan artists, including Kiluanji Kia Henda, Ndilo Mutima, Nástio Mosquito, Yonamine, and Ihosvanny. The exhibition, entitled ChecklistLuanda Pop, was built upon the Sindika Dokolo collection, one of the most extensive troves of contemporary African art. Both exhibitions—the African Pavilion and the Luanda Triennial—placed Angolan art on the map of contemporary creativity. Although the exhibition was framed for an international audience of “biennial-goers”, the international repercussion of the Pavilion had a deep impact both in the Angolan and Portuguese art scenes.

Concurrently, the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian intensified its focus on Global South art scenes and transnationalism, organizing exhibitions such as the touring Looking Both Ways. Art of the Contemporary African Diaspora (titled “Looking both Ways. Das esquinas do olhar” in Portugal 2005), and developing the Distância e Proximidade cultural program, which would evolve into Próximo Futuro in 2009, a five-year cultural forum addressing issues of migration, cultural identity and aesthetics from a global vantage point.

Looking Both Ways, Gulbenkian 2008The project adopted the form of an “observatory,” attentive to the relationship between cultural production and public life in Africa, Latin America, and Portugal. It also paid special attention to postcolonial debates emerging in the visual field, encouraging discussions with visual artists from non-European contexts. Próximo Futuro focused on the Atlantic relationship between Latin America, Africa, and Europe. Although the program justified the appropriateness of Portugal as a participant in those debates through its insertion into contemporary migratory fluxes, it also questioned the centrality of the country in more celebratory and Saudosista (or nostalgic) views of contemporary Portugal. Próximo Futuro would also be relevant for another reason: it epitomized the blurring of boundaries between art curating and cultural programming.

Looking Both Ways, Gulbenkian 2008The project adopted the form of an “observatory,” attentive to the relationship between cultural production and public life in Africa, Latin America, and Portugal. It also paid special attention to postcolonial debates emerging in the visual field, encouraging discussions with visual artists from non-European contexts. Próximo Futuro focused on the Atlantic relationship between Latin America, Africa, and Europe. Although the program justified the appropriateness of Portugal as a participant in those debates through its insertion into contemporary migratory fluxes, it also questioned the centrality of the country in more celebratory and Saudosista (or nostalgic) views of contemporary Portugal. Próximo Futuro would also be relevant for another reason: it epitomized the blurring of boundaries between art curating and cultural programming.

Furthermore, from the early 2000s Portuguese art institutions began exhibiting visual arts alongside many other cultural manifestations, including music, literature, theatre or cinema, lectures, thus becoming multimedia social and cultural venues. These institutions also diversified the range of cultural productions displayed on their walls. As a result, we find an increasing number of visual producers in the country adopting a more extra- and interdisciplinary tone. We will return to this point shortly.

Próximo FuturoThe commemoration in 2008 of the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue also had a decisive impact on shifts in cultural practices, introducing criticism of multiculturalism to public debates as evidenced in Žižek’s reflections (2006) on its repressive tolerance and the awareness of Santos’s (1999) notion of “subordinate belonging” used to address the mechanism of capitalism for social regulation (Lança e Vieira).

Próximo FuturoThe commemoration in 2008 of the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue also had a decisive impact on shifts in cultural practices, introducing criticism of multiculturalism to public debates as evidenced in Žižek’s reflections (2006) on its repressive tolerance and the awareness of Santos’s (1999) notion of “subordinate belonging” used to address the mechanism of capitalism for social regulation (Lança e Vieira).

4. Finally, from 2010 onward, curating and cultural programming have become more popularized, reaching broader segments of Portuguese society due to the urban transformation of Portuguese cities into creative hubs, as mentioned in the introduction. During these years, we can observe the consolidation of a reduced but strong body of scholarly work concerned with the structural impact of colonialism on the configuration of Portuguese society. With this debate occurring paradigmatically in the fields of history, anthropology and sociology, visual culture and its cultural politics of display would also become a crucial field for articulating critical positions. The increasing number of conferences, public lectures and cultural events focusing on colonial and postcolonial Portugal enhanced the visibility of artists and art projects, contextualizing and giving legitimacy to a range of ideas and voices, as art exhibitions and artistic interventions often engender critical discussion.6

Art criticism experienced a similar transformation during these decades, moving from the analysis of individual discourses to a more complex examination of the context in which these circulate, addressing how the institutions and networks that promote them operate.7 Scholarship from the past decade has stressed the minority presence of artists from former metropolitan territories (and more generally speaking from non-Western countries) in the Portuguese artistic landscape, while also deploring the provincialism and Eurocentrism of that landscape and criticizing the lack of interest in truly exploring the consequences of imperialism in post-dictatorship Portugal.8

In 2006, António Fernandes Dias work already provided the most exhaustive overview up to the present date in that direction. In this text, Fernandes Dias’s main concern is with discerning whether the rise of artistic discourses on difference allows us to conceptualize a true “postcolonial interest” in the Portuguese landscape. To this question, Fernandes Dias replied: “nos domínios das artes visuais—da crítica, da história, da curadoria, da própria prática artística—o silêncio e a invisibilidade sobre o não ocidental ainda são dominantes” (2006, 330). It is important to mention that, for him, this silence is not the consequence of a lack of artistic initiatives, rather it arises as a result of the indifference of the specialized context of art criticism: “Mesmo que desde há dez anos algumas coisas interessantes tenham acontecido, as reacções da imprensa especializada foram poucas e frágeis, e as consequências para um possível debate sobre a arte e a cultura contemporâneas numa situação globalizada, com múltiplos centros, multicultural e intercultural, foram escassas ou nulas” (2006, 330).

If the critical valorizations epitomized by Fernandes Dias confronted a panorama in which postcolonial discourses related to art were widely marginal—or at least not visible enough to foster debate within Portuguese civil society—recent contributions have shifted and diversified the areas of discussion. To cite just a few, these contributions have highlighted the importance of institutional platforms and programs in widespread postcolonial concerns (Restivo 2016); reflected on the weight of colonial visual tropes in the configuration of Portuguese contemporary creative languages (Beleza Barreiros 2009); delved into the decolonial potential of critical visual imagination (Balona de Oliveira 2016); addressed the continuities of emancipative discourses within cinematic practices and explored visual materializations of the idea of Portuguese exceptionalism (Piçarra 2014). Furthermore, updating Fernandes Dias’s insights on how mainstream art silences critical views on coloniality in Portugal, while also considering the emergence of more recent phenomena addressing issues of multiculturalism, globalization and difference, Inês Costa Dias (2009) has explored how curating challenges the “postcolonial amnesia” of Portuguese civil society and official institutions. The contributions provided by these authors attempt to confront how recent proposals are addressing the lacunae in Portugal’s postcolonial cultural configurations. They engage a cultural panorama in which, despite the proliferation of postcolonial-infused initiatives, the contradictions of postcolonial Portuguese reality have far from disappeared. It is to these contradictions as framed in cultural programming that we now turn.

Between Curating and Cultural Programming

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, Portuguese cultural and artistic institutions began introducing a decisive shift in their cultural policies. Although the figure of the curator has continued to play a pivotal role (remaining a place of social influence and cultural power at hand of only a few names), the visual is no longer considered a restricted terrain occurring within the walls of white cubes and affecting a reduced audience of connoisseurs. On the contrary, we begin to see art (and more specifically art concerned with the contradictions of the postcolonial Portuguese society) merging with activist processes, academic seminars and mixed-media festivals. From this moment onward, the display of contemporary art becomes articulated within larger infrastructural, cultural programming.

In seeking to understand the social economy of these practices of cultural programming, it is important to understand how European museums and cultural institutions have attempted to respond to the challenges of a predicament marked by migration and transnational flows.9 Artistic programming is part of these global public debates in the context of the political changes, and the cultural and demographic dynamics in a postcolonial Europe, all of which expose the increasingly apparent bankruptcy of multiculturalist models of mutual indifference and well-intentioned, yet superficial, recognition. The interest of Portuguese cultural and artistic institutions in showcasing artworks concerned with postcolonial topics is also subject to these limitations. In many cases, the main objective of a more “alternative” platform has been to reach a local audience not seduced by, or directly, yet unofficially, excluded from more formal cultural spaces.

We can point out several long-term projects such as Danças na Cidade (Mark Deputter 1995–2004), Festival Alkantara (Deputter until 2008 and Thomas Walgrave until 2018), the work of António Pinto Ribeiro in Culturgest (2000–2004), and the programs offered at the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (2005–2015), as mentioned above. The institutional artistic panorama became more diverse with the appearance of municipal institutions (Teatro Maria Matos - until 2018, Teatro São Luiz, Galerias Municipais), Hangar (a center for exhibitions, artistic residencies, and art studies), and Maumaus Lumiar Café. These spaces have developed seminars and multidisciplinary events with a special emphasis on coloniality, thereby engaging in the construction of cultural discourses synchronized with a Europe seeking to reimagine herself. Their agendas have generated a broader awareness of non-European, nonwhite cultural practitioners, providing local creators with different spaces of visibility concerned with more peripheral practices.

Hangar - Centro de Investigação Artística

Hangar - Centro de Investigação Artística

For example, part of Hangar’s program is developed through workshops with local Afro-descendant populations, which include not only students, but also musical and visual producers. For a general audience, “Hangar seeks to organize and produce the development of artistic inter-disciplinary projects and visual arts projects that focus on Lisbon as a central backdrop for contemporary culture.”10

Some cultural initiatives in Lisbon have increasingly strengthened the “transcultural” and interdisciplinary paradigms of artistic globalization, bringing to the fore heterogeneous perspectives within a widening geographic range of voices. Practices such as seminars, talks, conferences and workshops to stimulate the development of artistic and theoretical practices, which were considered minor not so long ago, have become popular. Some of these practices have been organized in close dialogue with art exhibitions, performances, music recitals, and staged readings, which have contributed considerably to inserting artistic creativity within a broader panorama while also “thematizing” the art. Permeated by a cosmopolitan spirit, and attuned to the major international debates, these institutions have foregrounded issues relating to postcolonialism, post-nationalism, the rescue of invisible histories, alternative modernities and ecologies of knowledge, the role of social movements, post-memory, migration, cultural globalization, ecology, feminism, and Black identity. These interests have become inserted into the public display of practices related to epistemologies of the South, subalternity and decolonial practices, and ongoing reexaminations of the place of speech and listening, developing a broader and involved vision of art.

In moving some political and academic subjects to the forums of discussion promoted by cultural institutions, into which artists and artistic discourses are also called, cultural programming has significantly altered the previously outlined panorama. Some limitations, however, still exist. First, when confronting these cultural productions, it is important to problematize the context in which they are produced and discussed. Determining whose voices are heard, and in which contexts and by whom, is always essential. A primary consideration has to do with acknowledging that their public remains quite circumscribed to a small and mainly “white” audience. This limitation has been recognized even in these cases, such as the Próximo Futuro program, which are driven by the inclusion of heterogeneous audiences and by ensuring democratic accessibility.11 Returning to the example that opened this article, for Ângela Ferreira the discussion on coloniality, at least in the visual art scene, has strived to incorporate those communities directly experiencing the most negative impacts of racial discrimination and exclusion. According to Ferreira, however, the risk lies in the fact that this array of practices (adopting a superficial postcolonial facade divested of a deeper preoccupation with the contradictions of Portuguese society) could risk covering up and naturalizing deeper inequalities deriving from contradictions which are at play in the present reality.

Dealing with this transition from individual artists and exhibitions into major, all-encompassing events, Maria Restivo (2016) has outlined how this development has not had the expected impact on Portuguese civil society, where the nostalgic Lusotropicalist vision of the imperial past still prevails.12 In her view, initiatives such as Africa.Cont13 or Próximo Futuro have been challenging this vision, not just by presenting contemporary art and cultural manifestations from “peripheral” African and Latin American contexts (not only Portuguese-speaking), but also by dismantling traditional assumptions that identify these territories with outdated, local scenarios. Nevertheless, Restivo argues, none of them has directly addressed the contradictions of Portugal’s postcolonial condition, eschewing these contradictions (again, in her view) by displaying an internationalist, global focus. Given that this last point is highly debatable, insofar as institutions such as Hangar or Teatro Maria Matos had developed a close collaboration with their local environment, what is true is that art can no longer be discussed outside of the predicaments of cultural programming.

We must not forget that the emergence of cultural programming is linked to an all-encompassing process of urban and cultural transformation in which Portuguese cities (especially Lisbon) are becoming major tourist and cultural destinations. The role played by artistic manifestations in the promotion and consolidation of the touristic appeal of Lisbon, its branding as a major multicultural European capital, and the connection between the exalting narrative of discoveries and the field of tourism, are issues that deserve further research. Elsa Peralta’s book Memória do império (2017) highlights “the several threads of representational continuity, which are traced considering the mnemonic imagination of the history of the Portuguese Empire, extending from Liberalism and the 1st Republic to the post-colonial period, especially from the mid-1980’s on, when, in the context of negotiating Portugal’s new symbolic positioning in the European space and the Portuguese-speaking world, a memory of the empire becomes re-organised within the national public space.”14 If we take the example of artistic practices emerging out of African or Afro-Portuguese communities which are exhibited in Lisbon, they are still framed within uncritical processes of cultural commodification or based on ideas of “Lusofonia,” in which Portugal appears as a center of reference that has articulated multicultural approaches to its own realities.15 The next section shifts the focus from curatorial processes and cultural programming to creative practices, in order to explore the contradictions involved in this process of cultural transformation.

Decolonizing the Portuguese Imagination

I see contemporary art as an imminently rhetorical and discursive space, which allows us to articulate complex criticisms, sometimes difficult in other artistic forms. This is a process that can be compared to that of the social sciences, but that has its specific features: for example, the associative capacity of images, a certain silence, a time that has everything to do with curatorial character, but also space, of an exhibition. This policy has always been essential for me; otherwise you would lose interest in art and try to find other forms of expression, other ways of living. —Pedro Neves Marques (Vahia 2017)

A younger generation of Portuguese creators (Afro-descendant or otherwise) is bringing to the public space marginalized histories and perspectives on the country’s history and contemporary sociocultural situation. The work of these creators is attentive to the multiple ways in which a supposed postcolonial debate can provoke a disavowal of criticism. At the same time, they are also exploring ways to challenge artists’ conventional role as visual producers and their relationship with cultural institutions. In the work of Grada Kilomba, Pedro Neves Marques, Vasco Araújo, Filipa César, Mónica de Miranda, Délio Jasse, Catarina Simão, Pedro Barateiro, and Rita GT, to mention just a few, the questioning of coloniality is related to the conditions affecting subjects and bodies located outside the main meta-narratives and imaginary of both the Portuguese past and its post-dictatorial, postcolonial present. These practices are playing a decisive role in decolonizing the Portuguese imagination, as Ana Balona de Oliveira (2016) has argued concerning the work of visual artists such as Délio Jasse, Daniel Barroca, and Raquel Scheffer.

An online platform such as Artafrica (launched in 2005 by the Fine Arts Service of Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and then managed by the Comparative Studies Center of University of Lisbon), which organized the first survey of contemporary visual artists from Portuguese-speaking African territories, or BUALA (launched in 2010), has become a reference in artistic and academic fields as a multidisciplinary platform exploring the synergies between art, theory, and activism and stimulating public debate about the lasting impact of racism and colonialism across Portuguese-speaking communities. This is also the case of initiatives such as Rádio AfroLis, an audioblog created in 2015 by Carla Fernandes, which has provided a forum for multidisciplinary cultural expressions by Afro-descendants living in Lisbon and fostered a critical questioning of the role of media and social platforms in representing such expressions.

This interest in recovering fragmented and contradictory memories is shared by some recent theater productions, as exemplified by Mala Voadora’s Moçambique (2016) and Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido’s Retornos, Exílios e Alguns que Ficaram (2014), and Filhos do Retorno (2018). While Moçambique is conceived “as a historical novel, [which] invents a story whose context comes from history,” Craveiro’s plays critically redefine and update the memories of communities who were in Africa during colonial times and provide subsequent generations who did not directly experience these events an idea of Africa that has remained as a family legacy. André Amálio’s trilogy Hotel Europa: Portugal não é um país pequeno (2015) engages with the impact of Portuguese colonialism in Africa, while Passa-Porte (2016) focuses on changes in nationality resulting from independence processes, and the ways in which Portuguese society receives these new citizens. Amálio’s Libertação (2017) deals with colonial war and the struggle for independence. Documentary and biographical theater offers one platform for retelling some invisible chapters of history and revealing the contradictions of various regime systems, and the disparities between institutionalized images and real-life impressions and perspectives.

Aside from these initiatives, we must not forget that another vast body of creative practices is taking place outside the walls of museums and art galleries. Artistic interventions, performances, and site-specific installations have become a common feature of many exhibitions curated over the last decade. Artists such as Monica de Miranda and Vasco Araújo have chosen landmark historic locations as venues, attempting to re-signify them. Perhaps the clearest example of this tendency, however, has involved curatorial projects. Over the past few years, several initiatives have appropriated the ideologically charged space of Belém in order to raise issues about the unresolved questions of Portugal’s colonial history. Retornar. Traços de Memória, curated by Elsa Peralta in 2015, arises from the commemoration of the 40th anniversary of African independence and the major influx of retornados, the population born or living in the former colonial territories that gained independence from Portugal in 1975. The project comprised several elements: the production of performances and a play on the experience of Portuguese colonizers in Africa, a series of talks, the collaboration between the artists Alfredo Cunha, André Amálio, Bruno Simões Castanheira, Joana Craveiro, and Manuel Santos Maia, and an artistic intervention in the Portuguese Padrão dos Descobrimentos. This controversial symbol of the Portuguese Estado Novo and colonialist memory politics has presented a program on issues of citizenship and racism, such as the exhibition Racisms (2017; which spanned the period from 1497 to the present), which focused on the “Portuguese case, though it will open windows onto a comparative understanding of racism as prejudice concerning ethnic background combined with discriminatory action,” the exhibition Atlântico Vermelho by the Brazilian artist Rosana Paulino (2017), and Contar Áfricas (2019), a museological exercise on the walls of the art institution in which the “exhibited pieces were hand-picked by researchers in the fields of anthropology, the arts, geography, history and literature who, over the course of their work, have studied Africa and related themes, or who have made methodological, pedagogic or civic intervention proposals that are entwined with the theme of the exhibition.” The presence of art within popular public spaces has therefore sought to familiarize broader segments of the population with artistic practices and, more importantly perhaps, to redefine symbolic places related to colonial histories.

The venues and contexts of such interventions have diversified, expanding the dialogue on Portugal’s postcolonial identity beyond the space of the museum and the gallery in order to connect more inclusively and expansively and open discussions with the cultural protagonists of so-called post-colonial Portugal (whose condition as such must always be contested). Another example of similarly themed cultural program was For us, by us: African and Afro-diasporic cultural production in debate organized in December 2018 by ArtAfrica, BUALA and the Associação Cultural Pantalassa. In this program, various Afro-descendant artists involved in different aesthetic languages (film, visual arts, literature, theatre, music) shared their work and discussed a range of issues about artistic production, public cultural policies, the restitution of African patrimony, how to build a career amidst the various worlds of influence, and the omnipresent and newly burgeoning wave of racism in Portuguese society. At the same time, Portugal’s anti-racism movement has been gathering steam in recent years, with public discussions centering on a range of topics, from the legacy of slavery and colonialism to the more publicized police brutality against people of color, most of whom continue to live in the worst conditions, in Lisbon and throughout Portugal.

Conclusions

We have seen how curating and cultural programming in the last decades of the twentieth century provided a platform to articulate concerns regarding multiculturalism and globalization that echoed the transformations of post-dictatorial Portuguese society. In the late 2000s, cultural programming sought to encompass artistic production and public discussions on racism, social exclusion and citizenship. In parallel, the number of Portuguese artists dealing in a systematic, critical way with the legacies of colonialism increased, while the approaches and issues dealt with also became more diverse.

The current situation emerges as the result of long struggles both at home and abroad: the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the civil rights movement in the United States; the demonstrations against police repression and the articulation of the Black Lives Matter movement; the Rhodes Must Fall movement in South Africa; and the Decolonize This Place initiative.16 There is no doubt that these initiatives have had an impact on the Portuguese context. Some examples would include the discussion generated in 2017 about the recently erected statue of Father António Vieira in Lisbon; the intellectual and public reactions to the speech by Portugal’s president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, concerning slavery; a protracted discussion about the Lisbon City Council’s Museu das Descobertas (Museum of Discoveries) project; and the amplification of the debate on racism due to the rise in police violence in low-income neighborhoods in January 2019. In the first case, the demonstrations organized by the Descolonizando collective against the commemoration of Vieira were justified by alluding to the implication of Vieira in the Portuguese slavery system. These actions were met with “retaliation” from Portuguese far-right groups who gathered to ensure the so-called safety of the statue, yet the major outcome of the dispute had to do with the statue’s public relevance. Portugal’s colonial legacy has ultimately become a flashpoint for public discussion, triggering a sometimes very militant reaction. The second episode was in response to the commemorations of the 40th anniversary of independence of the Portuguese-speaking countries of Africa. Despite (or because of) Rebelo da Sousa’s tepid condemnation of slavery and his reinforcement of Lusotropicalist imagery, race and racism served as a focal point in the corresponding social debates on Portuguese identity. Finally, the idea of building a museum dedicated to Portugal’s role as colonizer fueled a national discussion on the dissemination of Portuguese history, consolidating an academic resistance to the official narrative of the discoveries, and questioning the very name and meaning of such a museum. The articulation of an incipient concern about these processes has countered the sense of “desmemorização” (amnesia) linked to the official politics of memory, which is “um processo muito mais subtil do que o revisionismo histórico. Não adultera os factos, mas o quadro em que os interpretamos” (Barata 2017).

In any event, there is an urgent need to bring burning issues such as the role of Portugal in the Atlantic slave trade and the impact of Portuguese colonization in the Americas to the forefront and to challenge the myth of Portugal as a benevolent or “soft” colonizer. Despite the efforts of many cultural agents, in Portugal many Black citizens and racialized groups are treated as immigrants, having a higher possibility to be legally punished and restricted access and visibility in public and political spaces. Fortunately, within the last five years there have been far broader discussions about the persistence of racism, particularly in terms of everyday situations and systemization. In particular, public opinion in Portugal has come to at least partially acknowledge, for the first time, the positive aspects of anti-racist and emancipatory struggles which many racialized groups and individuals have been grappling with for years. The media has also made some groundbreaking contributions by exposing certain hidden realities. Such exposés obviously reach large numbers of the general population.17 Some academics have also shown a greater involvement in anti-racist causes. One aspect of the debate is the need to make the accountability of the ethno-racial elements linked to socioeconomic inequalities. Formed in July 2018 from a collective of activists, academic and artistic women, the Instituto da Mulher Negra em Portugal (INMUNE)18 has provided a link between Black identity, feminism, and the anti-racist movement.

It is important to note that this recognition is to a large extent the result of the efforts of a new generation of people of color expressing themselves in their own words and voices. The discussions concerning decolonization of academic curricula in Cape Town and London (promoted by SOAS students) has also slowly begun to have an impact in Portugal. The consolidation of a denser institutional texture and the existence of these platforms in line with international cultural agendas—inaccessible to artists operating only a decade earlier—and the increasing interest in Postcolonial Studies at universities all serve to shed light on the multiplicity of discourses mentioned by Ferreira. Moreover, recent initiatives are addressing how history is taught at public educational institutions (Roldão 2018). These include Roteiro para uma Educação Antirracista (Roadmap for an Anti-Racist Education) which explains the role of racism as a foundational element in the narratives of Portuguese nationhood (see Maeso and Araújo 2017). The project to erect the first memorial to slavery in Portugal—to be built along the Lisbon waterfront near the site of Casa dos Escravos (a former slave prison)—is a good indicator of the transformations that we have analyzed in this article.

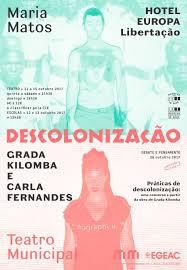

The display of contemporary art and visual creativity provides a valuable platform to confront the politics of postcolonial memory and remembrance in Portugal, although, as we have seen, some limitations still remain. Despite the strength and public relevance of some of the analyzed initiatives, and the consolidation of a broader public concern around the importance of place and voice among the heterogeneous subjects involved in the definition of Portuguese postcolonial identity, racialized communities continue to have little visibility in the realms of academia, the arts or the media, or in cultural circles in general, and they also have considerable difficulties in accessing the circuit of contemporary art in terms of production and spectatorship.19 Undoubtedly, some practices have sparked the attention of more expansive audiences by focusing on the intersection between race, class and gender, while also framing more localized discussions within broader frameworks. This is the case of the cycle Descolonização (“Decolonization”) organized by Liliana Coutinho in the former Teatro Maria Matos (2017), which brought activists and representatives of anti-racists cultural organizations into dialogue with writers, musicians and visual creators.

ciclo Descolonização 2017

ciclo Descolonização 2017

The institution also invited Grada Kilomba, on the occasion of her first exhibitions in Portugal. Kilomba, a Portuguese-born Afro-descendant visual creator and theorist living in Germany, provided a controversial and out-of-the-box approach to the contemporary Portuguese curatorial and cultural scene. The resulting discussion was followed by a heterogeneous audience extending far beyond the usual (art-going) suspects generally found at exhibition openings or academic conferences in Lisbon. It also attracted a vast media coverage. In this sense, this exhibition provides a good example of how artists are actively shaping broader debates on identity and social participation at the heart of Portuguese society.

The consolidation of cultural programming and the integration of artistic practices within broader cultural productions run the risk of isolating and “thematizing” issues of race and difference, potentially establishing a distance between the issues addressed and how they are actually experienced within the Portuguese context, while also prioritizing short-term interventions and cultural actions as opposed to ongoing observation, analysis, and engagement.

Agora somos todos negrxs?, São Paulo 2017

Agora somos todos negrxs?, São Paulo 2017

This becomes even more evident if we compare the Portuguese case with other contemporary art scenes such as in Brazil, where Black artists show, as Daniel Lima, the curator of Agora somos todxs negrxs! states “uma articulação, um grupo de colaboração, de conhecimento e contaminação mútua da produção.”20 The same curator also notes that art can follow a process of ethical construction, while at the same time reflecting on how to organize such a narrative. The initiatives examined here, finally, are symptomatic of a significant transformation in the Portuguese cultural landscape, yet one that is not exempt of contradictions. In this landscape, visual practices are playing a pivotal role but there is still much progress to be made toward adopting a truly postcolonialist stance, one where the terms under which subversive cultural action and resistance against commodification and cultural politics are being thought out and reconsidered.

Bibliography

Aderaldo, Guilhermo and Otávio Raposo. “Deslocando fronteiras: notas sobre inter- venções estéticas, economia cultural e mobilidade juvenil em áreas periféricas de São Paulo e Lisboa.” Horizontes antropológicos 45 (2016): 279–305.

Arenas, Fernando. “Migrations and the Rise of African Lisbon: Time-Space of Portu- guese (Post)coloniality.” Postcolonial Studies 18.4 (2015): 353–66.

Balona de Oliveira, Ana. “Descolonização em, de e através das imagens de arquivo ‘em movimento’ da prática artística.” Comunicação e Sociedade 29 (2016): 107–31.

62 Luso-Brazilian Review 56: 2.

Barata, André. “‘Maafa’: o grande desastre.” Jornal Económico (20 April 2017). http:// www.jornaleconomico.sapo.pt/noticias/maafa-o-grande-desastre-14...

Belanciano, Vítor. “O triunfo da Afro-Lisboa” Público (28 June 2015). http://www. publico.pt/culturaipsilon/noticia/o-triunfo-da-afrolisboa-1...

Beleza Barreiros, Inês. Sob o olhar de deuses sem vergonha: cultura visual e paisagens contemporâneas. Lisbon: Colibri, 2009.

Costa Dias, Inês. “Curating Contemporary Art and the Critique to Lusophonie.” Arquivos da memória 5–6 (2009): 6–46.

Fernandes Dias, António. “Pós-colonialismo nas artes visuais, ou talvez não.” In ‘Por- tugal não é um país pequeno’. Contar o Império na pós-colonialidade, Ed. Manuela Ribeiro Sanches. Lisbon: Cotovia, 2006. 317–39.

Fradique, Teresa. Fixar o movimento: representações da música rap em Portugal. Lis- bon: Dom Quixote, 2003.

Garrido Castellano, Carlos. “Curating and Cultural Difference in the Iberian Con- text. From Difference to Self-Reflexivity (and Back Again).” Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research, vol. 24.2 (2018): 103–22.

Gorjão Henriques, Joana. Racismo em português: o lado esquecido do colonialismo. Lisbon: Tinta-da-China, 2017.

Lança, Marta. “Ainda pensamos o outro como o Outro? Tendências da programação do pós-colonial em Portugal” Unpublished text.

———. “Lusosphere Is a Bubble.” 2008. http://www.buala.org/en/games-without- borders/lusosphere-is-a-bubble

Lança, Marta e Vieira, Ana B. “Desta nossa-de-todos Lisboa, sobre os espe- táculos de Outras Lisboas.” (2008) Text originally published in Le Monde Diplomatique and available at: http://www.buala.org/pt/palcos/desta-nossa-de- todos-lisboa-sobre-os-es...

Lourenço, Eduardo. O labirinto da saudade. Psicanálise mítica do destino português. Lisbon: Gradiva, 2000.

Maeso, Silvia and Araújo, Marta. “The (Im)plausibility of Racism in Europe: Policy Frameworks on Discrimination and Integration.” Patterns of Prejudice 51.1 (2017): 26–50.

Quijano, Aníbal. “Colonialidad del poder y clasificación social.” Journal of World- System Research 6.2 (2000): 342–86.

Peralta, Elsa. Lisboa e a memória do Império. Património, museus e espaço público. Lisbon: Le Monde diplomatique, 2017.

Piçarra, Maria do Carmo. “Azúis ultramarinos: imagens-clarão do colonialismo por- tuguês no cinema.” In: Imagens coloniais. Revelações da antropologia e a arte con- temporânea, edited by Nuno Faria. Guimarães: CIAJG, 2014. 71–96.

Pinto Ribeiro, António. “Programa Próximo Futuro chega ao fim.” Público (Sept. 4 2015). https://www.publico.pt/2015/09/04/culturaipsilon/noticia/uma-ponte-com-o...

Ramalho, Maria Irene and António Sousa Ribeiro (Org.). Entre ser e estar: raízes, percursos e discursos da identidade. Porto: Afrontamento, 2002.

Restivo, Maria. “O pós-colonialismo e as instituições culturais portuguesas: o caso do programa Gulbenkian Próximo Futuro e do projeto Africa.Cont.” E-Revista de Estudos Interculturais do CEI-ISCAP 4 (2016): 1–19.

Ribeiro, Margarida Calafate and Ana Paula Ferreira. Fantasmas e fantasias imperiais no imaginário português contemporâneo. Coimbra: Campo das Letras, 2003.

Roldão, Cristina et al. “Imigração e escolaridade: trajetos e condições de integração.” Desigualdades sociais: Portugal e a Europa. Lisbon: Mundos Sociais, 2018: 301–314.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. A construção multicultural da igualdade e da diferença.

Coimbra: Centro de Estudos Sociais, 1999.

———. “Between Prospero and Caliban: Colonialism, Postcolonialism, and Inter-

identity.” Luso-Brazilian Review 39.2 (2002): 9–43.

Smith, Terry. Thinking Contemporary Curating. New York: Independent Curators International, 2012.

Teixeira Pinto, Ana. “The Art of Gentrification: The Lisbon Version.” Afterall 45

(Spring/Summer 2018): 88–97.

Tomás, António. “Descolonização e racismo à portuguesa” Publico, 20th May 2017.

https://www.publico.pt/2017/05/20/politica/noticia/descolonizacao-e-raci...

portuguesa-1772253

Vahia, Liz. “Entrevista com Ângela Ferreira.” ArteCapital. 2014. http://www.artecapital.

net/entrevista-167-angela-ferreira

———.“Entrevista a Pedro Neves Marques.” ArteCapital. 2017. http://www.artecapital.

net/entrevista-223-pedro-neves-marques

Vale de Almeida, Miguel. Um mar da cor da terra: raça, cultura e política da identi-

dade. Oeiras: Celta, 2000.

———.“O Atlântico Pardo: antropologia, pós-colonialismo e o caso ‘lusófono.’” In

Trânsitos coloniais: diálogos críticos luso-brasileiros, edited by Cristiana Bastos, Miguel Vale de Almeida and Bela Feldman-Bianco. Lisbon: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2002. 23–37

Vanspauwen, Bart and De La Barre, Jorge. “A Musical Lusofonia: Music Scenes and the Imagination of Lisbon.” The World of Music 2 (2013): 119–46.

Žižek, Slavoj. Elógio da intolerância. Lisbon: Relógio de Água, 2006.

Notes on Curatorship, Cultural Programming and Coloniality in Portugal

Luso-Brazilian Rev. December 2019 pp. 56:42-63.

- 1. We have recently dealt with this question. See Lança (2017), Garrido Castellano (2017)

- 2. On this topic, see Belanciano (2015), Teixeira Pinto (2018).

- 3. The Fundação Gulbenkian was created in 1956 and since then has played a central role in the Portuguese cultural and artistic milieu, funding art exhibitions, research and dissemination projects. On its part, the Fundação de Serralves opened its doors in Porto in 1989.

- 4. This becomes evident by the regular inclusion, since its last four editions, of artists from Portuguese-speaking African countries in the Banco Espírito Santo (now Novo Banco) Photo Prize, a major photographic prize.

- 5. For an in-depth criticism of the exhibition, see Costa Dias (2009).

- 6. The development of projects such as the History and Image Workshop of the Nova University in Lisbon, the symposium “Colonialismo Invertido,” organized in the Fundação Serralves as part of the exhibition in Porto of the 31st São Paulo Biennale, and the “Império and Arte Colonial” coordinated by the CHAM in 2017 can be mentioned as examples of this interest.

- 7. The evaluation of the cultural policies organized in 1998 and 2000 on the occasion of the Quincentennial of the “Discovery” of Brazil, and the first critical appraisals of initiatives such as Próximo Futuro or Africa.Cont can be mentioned here. We have dealt with this panorama in REF2.

- 8. Humanities and social science curriculums in Portugal still lack approaches to contemporary art manifestations emerging from non-European contexts.

- 9. Initiatives such as the MeLa. European Museums in an Age of Migration or the Former West research projects exemplify this trend. See http://www.mela-project. polimi.it/

- 10. https://kadist.org/program/affective-utopia/

- 11. As António Pinto Ribeiro explained: “FCG é uma organização complexa porque sendo simultaneamente uma máquina com raras capacidades de produção e difusão é também um poderoso instrumento de poder e da sua distribuição. Esta situação gera um paradoxo que começa por se sentir no interior, com muitas dificuldades de contágio entre áreas, e depois no exterior, onde as questões de uma cultura contemporânea crítica têm dificuldades em tomar lugar” (2015).

- 12. The increasing visibility of art from Portuguese-speaking African countries in the international art arena (and the shift in the economic and political balance of Portuguese-speaking African countries in relation to Portugal) also increased the interest for Afro-descendant communities living in Portugal and their expressions. See Belanciano (2015), Arenas (2015).

- 13. . Africa.cont was presented as a project that would allow for the creation, in Lisbon, of a “multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary center for the knowledge of Africa and its diasporas in their contemporary developments,” but it never secured a physical space.

- 14. The activity of cultural associations such as Batoto Yetu, which is organizing critical guided tours to places dominated by the presence of African communities in Lisbon, can also be referenced here. An interrelated initiative is the phenomenon of cultural tourism engaging Lisbon’s “bairros periféricos.” Regarding this development, see Aderaldo and Raposo (2016).

- 15. This has been a central preoccupation concerning musical industries. See Fradique (2003), Vanspauwen and de la Barre (2013). On the narrowness and paternalism of Lusofonia from a Portuguese perspective, see Lança (2008).

- 16. Decolonize This Place is a space, action-oriented movement dealing with and connecting Indigenous struggles, Black liberation, Free Palestine, as well as labor and anti-gentrification initiatives.

- 17. In particular the series Racismo em português (2016), on the African side of colonial history, and Portugal dos brancos costumes, on the multiple perspectives of racism, by Joana Gorjão Henriques, published before in Público newspaper then compiled as books (2017).

- 18. Black Women’s Institute in Portugal with Joacine Katar Moreira as president.

- 19. Attempting to counter this tendency, a workshop organized by Hangar in September 2017 invited curator Simon Njami to interact with Afro-descendant art students.

- 20. The exhibition took place in Galpão VB, São Paulo, between August and December 2017. It included the participation of Ana Lira, Ayrson Heráclito, Dalton Paula, Daniel Lima, Eustáquio Neves, Frente 3 de Fevereiro, Jaime Lauriano, Jota Mombaça, Luiz de Abreu, Moisés Patrício, Musa Michelle Mattiuzzi, Paulo Nazareth, Rosana Paulino, Sidney Amaral and Zózimo Bulbul.