Our Lady of the Chinese Shop, interview with Ery Claver

We revisited the film Our Lady of the Chinese Shop, by Ery Claver, which we played at the Casa do Comum in Lisbon, coincidentally at the same time as the Portuguese Cup final (May 25), and even so the room was packed and the audience still stayed for a long conversation based on the film. We wanted to end the intense seminar “Como se constrói um país,” (How to build a country) as part of the celebration for the 50th anniversary of Angola’s independence, with this contemporary film that reflects the urgent Luanda. A city where many beliefs, deep pain, mourning, greed, tragedy, betrayal, despair and disorientation coexist. Where people believe in anything that can help them, where power is a violent mirage.

Our Lady of the Chinese Shop had its world premiere at the Locarno Film Festival 2022 and was shown at international events in cities such as London, Rio de Janeiro, Ghent, Turin and Amiens. It also passed by Lisbon, but too discreetly. We believe it should be much more widely seen, as it’s a remarkable work. Geração 80, the production company behind the movie, which has contributed so much to inscribing Angola into the world, with all its strength, creativity and belief in cinema’s power to open minds, is 15 years old! Our friends and partners deserve a round of applause, we’re from the same batch, BUALA and Geração 80.

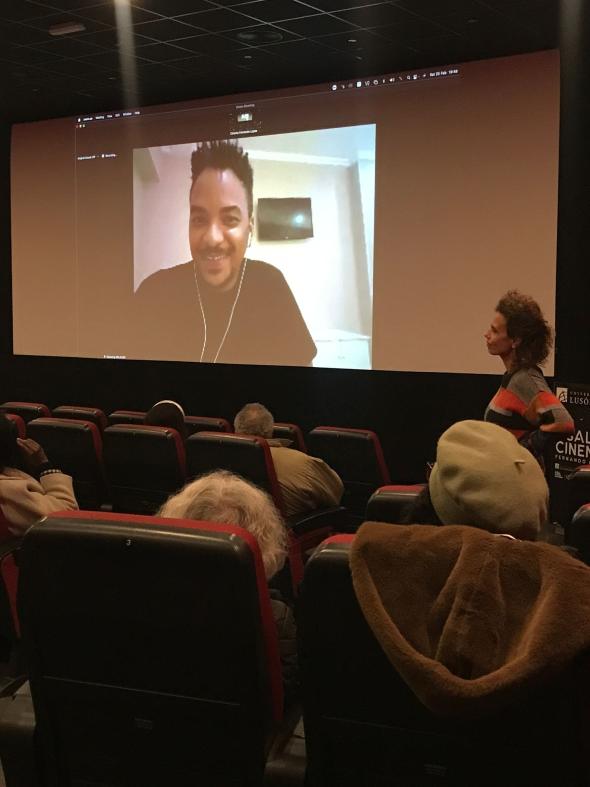

Cinema Fernando Lopes, 1 mar 2023

Cinema Fernando Lopes, 1 mar 2023

Ery Claver (Luanda, 1986) is one of Angola’s most versatile filmmakers. He began his career as a cameraman, working on numerous television programs and documentaries. He joined Geração 80 in 2013, where he developed his style as a photography director, for example in the short films Concrete Affection - Zopo Lady (2014) and Havemos de Voltar (“We will return,” 2017), both by Kiluanji Kia Henda and produced by Geração 80. Ery Claver has made several short films, including Lúcia no Céu com Semáforos (“Lúcia in the Sky with Traffic Lights,” 2018), in partnership with Gretel María, and Enóquio que Não Tinha Coração (“Enoch Who Had No Heart,” 2020), with his brother Evan Cléver. He was also director of photography on Fradique’s incredible Ar Condicionado (“Air Conditioning,” 2020), which won international awards. In 2022, he made his first feature film, Our Lady of the Chinese Shop. Here’s an interview with the director for BUALA:

You write the script like a poem or jazz piece.

You were already a co-writer on Ar Condicionado. We float along narrative lines without quite grasping them, as the narrator himself says, “recreating (or imitating) arbitrary pieces of life.” How do you work on that boundary between the arbitrary and wat is definitive in a film?

I build my scripts this way because I don’t have narrative experience and I find the power of the image in so few frames much more interesting. I also did this with the short Lúcia no Céu com Semáforos, which is basically a filmed poem. And so, I felt that I gained a lot of confidence in the act of writing my “scripts.” I’ve found that it’s the only way to write a script without it seeming boring, because I’ve always found the idea of the formal movie script very rough. All the rules and technical formalities are too dry for me.

The Chinese narrator is “a kind of Talking Cricket telling that story.” Why this outside/inside look? What’s the relationship with the economy, in geopolitical terms?

In recent years, one of the most prominent debates in the news is the relationship between China and not only with Angola of course, but also with other countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa. They have invested so much in the continent that they’ve become a major economic force, and their impact on the region is indelible. However, it remains such a controversial subject that many artists find it difficult to engage with. It’s a very important subject, not easily filtered into a specific format.

Luanda is like any city in a country once colonized by European powers, who saw Africa as an inexhaustible well of resources. As a result, our country is divided between imposed cultures and continues to poorly negotiate its identity between the past and the present. Not only in the way it constantly looks to the past, particularly by trying to distance itself from its colonial history, but also in the way it focuses on more contemporary issues. I wanted to question whether these external influences on the continent are new attempts at exploitation, or whether they’re simply another form of imperialism, albeit much more subtle in the purely economic field. Foreigners who arrive in a city for its economic potential and do everything they can to collect the resources without making it entirely clear that they’re taking control.

It’s now commonplace to say that in Luanda, reality surpasses fiction. Tell us a bit about your personal relationship with the city, I can tell you’re still fascinated by your own city and its mutations. The film refuses to exoticize it, even so.

My relationship with Luanda isn’t without a sort of exotic fascination too, but I see it more as a distorted exoticism. It’s a new city in the way we scale it artistically and I’m always looking for better concepts to understand it, different from those usually told from an external point of view. And this research has given me a glimpse of the complexity of our social context. Our reality is often contradictory, oneiric, almost unreal and difficult to decipher. The film confronts this reality because, I believe, as artists we have to confront reality the same way that reality confronts us.

The film proposes a reflection on power, revenge and the staging of power. How do you see the relationship between political leaders, the people, and religion with the social situation and a growing number of cults?

My film is philosophically complex and tinged with a dark romanticism. The premise of a Chinese shopkeeper displaying a plastic doll of the Virgin Mary in Luanda, the capital of Angola, and this object supposedly having the power to influence the lives of many local inhabitants, comes across as a scathing and even jocular paradox; a holy figure originating in the Middle East, made Caucasian by the West, and, in the film’s case, sold and distributed to Africans by a Chinese man as a form of control and manipulation. These dichotomies help me question “power” in an interesting way without bordering on the shallow analogy of bad guys versus good guys. There’s no Manicheism here.

What are your cinematic and aesthetic inspirations? Pedro Costa, Ingmar Bergman, Wong Kar-Wai?

Today I view my artistic influences more broadly. It’s clear that each movie I work on offers me different nuances of inspiration. In the case of Our Lady of the Chinese Shop, I embraced literature much more in the sense of understanding the visual power of prose. I dare say that my film is as much a literary product as a cinematographic one. I never watch movies while I’m writing because I don’t like to be influenced or intimidated by external “visions.” On the other hand, I read a lot and there are many authors I love, mainly Latin American and Mexican, with that kind of magical touch, that approximation between the real and the unreal that, at certain moments, fit together well. You could forget you’re reading something supernatural, it seems perfectly natural. Some of the things I like to read are more visual than some of the movies I watch. This gives me freedom because we work on a very limited budget, with very few resources. Sometimes it’s not good to define things so bluntly, like the setting, for example. If I imagine a scene around two characters sitting at a table and we can’t find a table, then we remove the table and do it on the floor. For me, the important part is the feeling, the atmosphere of the scene, not the setting.

Tell us how about the production of the film, during the pandemic, a small structure, “but we had a story that we wanted to film, that we wanted to see told,” this brings more authenticity to the film.

Filming during the COVID pandemic was obviously challenging, but I must admit that it offered me structural advantages because I was able to devote time to the script and, with Jorge Cohen as the film’s producer, we faced the production challenge with a definitive eagerness and urgency. This condition ensured that we took on the production of the film without fear of making mistakes and also as an antidote to the idleness and uncertainty of the future. A good example is the stadium scene: when I wrote it, I imagined a crowd, but then Covid arrived and we couldn’t even fit five people in. I was never afraid, because I know that reality and this mixture of magic forced me to find other ways of representing the same feeling. I know it may sound theoretical, but I think it’s very real and rational. Because we’re used to living like this in Angola. We have to make do with what we have, even for movies. We don’t have cinemas, but that doesn’t mean we don’t watch movies. We recreate our cinemas, our cinema proper, because we don’t expect anything from others, we support each other.

Fernando Lopes Cinema, 1 March 2023

How do you see, in your career and collaborations, the contribution of Geração 80 to the inclusion of Angolan cinema in the conversation with the world?

Although I didn’t have an academic background in cinema, I feel I’ve been very privileged with the experiences I’ve had at a professional level. Not just with Geração 80. I learned a lot in the years I worked at Semba Produções, I drank a lot from the bohemian ramblings with the artists in downtown Luanda. But it was really in Geração 80 that I had the opportunity, and with great pride, to not only be part of this renaissance of Angolan cinema that has so far allowed us to create a new social imagery in the field of auteur cinema through our films, but also to be able to participate in the effort to promote Angolan and African cinema in general through dissemination platforms, with projects such as Cine Zunga and Cine Geração.