“To play music, it is necessary to read people”, an interview with artist and Dj Lucky

Luquebano Afonso, better known as Dj Lucky, presented the installation Kokawusa, which in the Lingala language of his childhood, means “clothesline” (it took place at the Todos Festival, and will be announced elsewhere soon). The piece sums up his trajectory: words as lessons, the “panoafricanos” (African fabrics) of the merchant family, his collector spirit (of records and clothes), music and emotions that, as a DJ, he is used to manipulating. The installation is the pretext for talking about his life path. Balanced between various cultures, he has lived for 31 years in a more open and diverse Lisbon, an openness and diversity to which people like Lucky have contributed so much, from building the city to making the city dance.

This is a city of hard times, but also of encounters and possibilities with which he has grown up. In this text, we are led by the memories of Dj Lucky, between various sound tracks of quisange, semba, and afro blues, and multiple tracks on the floor, from Kinshasa to the Graça neighborhood, passing through Luanda, Cova da Moura, and Bairro Alto.

© DJ Lucky

© DJ Lucky

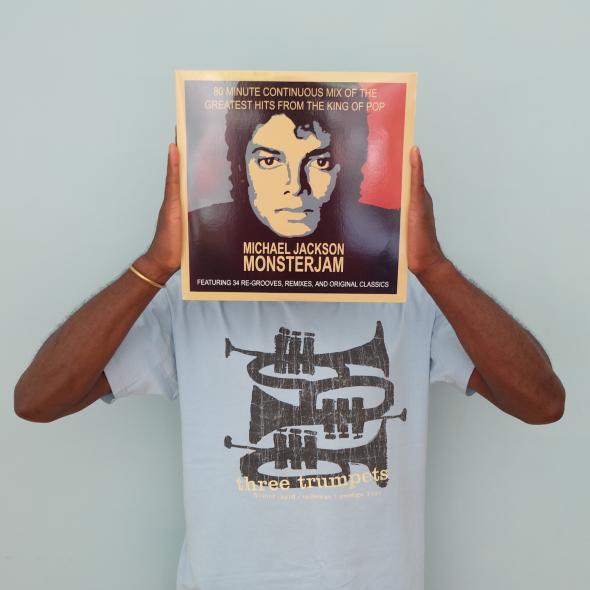

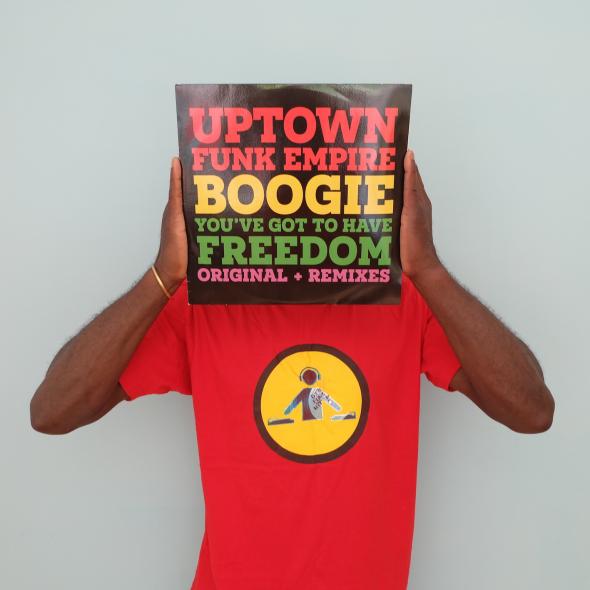

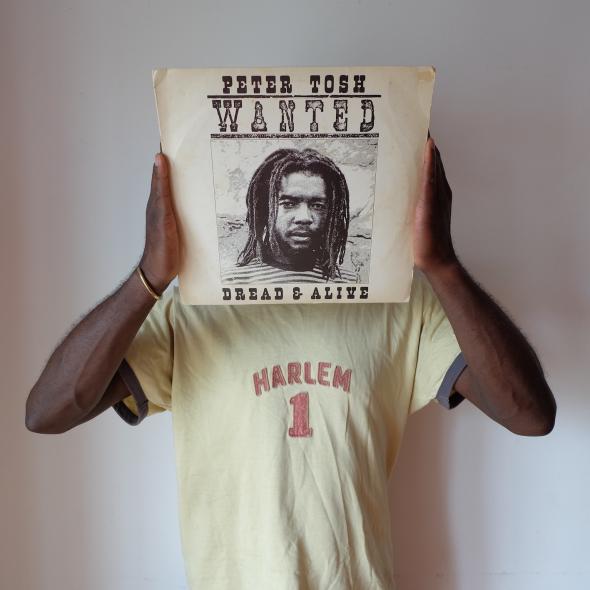

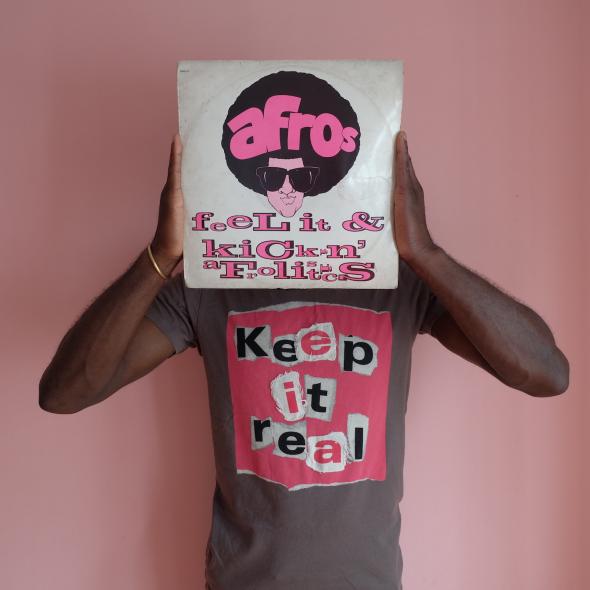

The “Kokawusa” installation

It is the realization of an old dream, that of articulating visual work to that of record collecting. It relates to the desire to preserve memory, to search for roots, transmission, and continuity. “To bring the memory of my grandmother to my daughter.” And, in this case, the memories are expressed in photographs of the author with vinyl (who has even considered printing them in silkscreen), cloths, and quotes from Bob Marley, Patrice Lumumba, Lélia González, Ângela Davis, and James Baldwin, and a sound manifesto entitled “Express yourself”, produced by Ninho Marimbondo (Lucky and Dedy Deaad) in a Beat Activism tone, in a water-like sound, with piano played by his 9-year-old daughter, quisange and rattles.

“Kokawusa” means clothesline in Lingala, and putting clothes out to air or to dry after washing, has something of renovation. But the initial idea “was to build a kind of hut, a house with a roof where our grandmothers would spread the food out in the sun so as not to let it rot, as is done with dried fish. It starts from the ideia of preserving, of making use of everything, make canned fruit from the peel of the fruit. Then it also had to pull in the clothes, a lot of “panoafricanos” (with its conceptual art). From pano-African to pan-Africanism. It’s a clothesline, but, in fact, we are preserving something. We want to give that such longevity (musika, in Lingala) that transforms. Extend the memories, keep the essence, in a transmission from the origins to today’s place, from the grandmother to the daughter and to all of us and, as if it were dried fish, to preserve them.”

From Angola to the Congo to escape the war and back to Angola

Luquebano Afonso, better known as Dj Lucky, was born in Kinshasa in 1968, where his parents, Angolan traders from Uige, Maquela do Zombo, moved because of the war in Angola. Of Kinshasa he remembers vague aspects, such as the music scene and the city’s noise, which is full of commerce, cloths, and colours. He remembers of studying at a Catholic school, and the flavors like his grandmother’s kikuanga, when he visited her during the holidays. He remembers watching grandmother roasting jinguba (peanuts) and bobó. He also remembers his father glued to the radio, trying to find out what was happening in Angola, and as soon as independence came about in his country, the family decided to return home. However, at that time, traveling by plane was a mirage, and with the very complicated roads, the only way was military trucks that have the strength and power to take people. His father went ahead in 1976, and his grandparents, Luque, his younger brother, and his mother, with the third child in her womb, followed in a military jeep on their way to Uíge, where Lucky stayed for a year with his grandparents while his parents prepared the ground in Luanda. His cousin Mawete João Baptista, the first ambassador, nominated under the MPLA government, had been assigned to Algeria, and left them the house for a while to they can settle in Luanda.

From that trip in the military jeep, he retained a sense of both concern and adventure: “we were going through the woods, you couldn’t see any towns, only the landscape, which was beautiful, but night and day, day and night. We’d stop to rest for a few hours and then go on. It was a bit crazy for me, but when I look back, I think: what an adventure!

Although Lingala is often spoken in Angola, and the Congolese scene is always present, one should remember that Cabinda is in a triangle with the two Congos, Brazzaville and Kinshasa, and the language circulates, he found it strange to speak in Portuguese because in the Congo he spoke only in Lingala and French. “When I arrived, I didn’t know how to speak a word of Portuguese. In Kinshasa I was in the third class, and I had to return to the first class because of the language. It was difficult to have friends my age, they were already super advanced. But I managed to make a life for myself there. I found some cool classmates and teachers and quickly managed to learn.”

It was the time of socialism, and of the Cuban teachers, “many ended up staying and building a neighbourhood, there in Primeiro de Maio.” He lived in his cousin’s house in Vila Alice, in the central area, near Largo Primeiro de Maio, of the Sagrada Família, which led to Alvalade, and not far from Bairro Operário. The war was going on outside the city, before 1992, but there were repercussions on the economy, on access to goods, and, above all, on the mobilization of boys to join the war battalions. He may not have felt the civil war (between UNITA and the MPLA and its huge external instrumentalization) directly, but the raids for the army were frightening. “It was every man for himself.” And Lucky only got away with going to war, or possibly he’s only here telling us this because he had polio. “My parents got me treatment for the leg problem to the point where I could walk. A lot of people in my day weren’t that lucky. It’s like that band Staff Benda Bilili who play in wheelchairs. When I arrived in Luanda, I automatically got an exemption from the army. I carried a paper justifying it. You can only notice the led problem when I’m standing up and walking. Sometimes, the soldiers came to me to take me away, and I showed them the paper. In other words, I was partly frustrated because I didn’t want to have that problem with my leg. The Angolan basketball team is one of the best, Jean Jacques, etc., so I wanted to play, but I couldn’t. But the truth is that this saved me from joining the military on disability.”

The raids took place in schools, on the streets, or in the poorest neighbourhoods. Sometimes “information would leak out in the neighbourhood: ‘Look, there’s going to be a raid here,’ and whoever could, would hide so as not to be seen. The soldiers came in jeeps that we called Azulinhos (little blue cars). They didn’t hit, but they brutalized. They would say, ‘Go there, get the guys you think have the body for military life.’” And then the boys would disappear to the despair of the parents who would try to find information, sometimes receiving a letter indicating that their son was already in Huambo or on another fighting front.

He lost a lot of friends or, when he found them again, a mine, some bad luck, and they were already crippled. “There were cases where they managed to stay in a post without going directly to war. It was a stupid war, fighting your brother. You didn’t understand it. But it was our reality, it was our youth…” Despite this permanent alertness, Lucky and his Luanda friends would improvise a few little parties. The parties during the war started at school, because they didn’t always have classes. “I also keep that energy from the parties in the musseques.”

In the 1980s, Luanda did not have that many foreigners apart from Cubans, Russians, and a large Congolese community. The latter often came to Luanda to get passports to travel to Europe. Having roots and influences, speaking good French, Lucky helped many of them pass for Angolan and come to Europe. Luanda had few people in general. The massive influx from the provinces occurred mainly after the war came to Luanda in 1992, in the interval between the Bicesse and Lusaka Agreements. Then “everything accelerated and got out of control, it changed almost everything, people started fleeing the provinces.” And another aspect is that you didn’t know the country because you couldn’t move around, there were mines everywhere, “it was difficult to get from one province to another. By chance, I went to Huambo, but by military plane. But we always stayed in Luanda.” Now that he can move around freely, Lucky would love to go back to Angola and visit all the provinces.

School didn’t offer much of a future either. “My father had a business in sawmills, he bought logs and extracted wood, he set up a carpentry shop, I saw money circulating.” Young people started doing muamba (going to Brazil to buy goods to resell in Angola), “but that wasn’t my interest, I wanted to continue studying. I wanted to leave and go to France.” However, it wasn’t easy to leave with your life planned if you weren’t “the son of a minister or parents with some privilege in the country. Only the children of ministers or the rich had scholarships to the United States or France. Many didn’t even return to their country, they ended up settling in Europe. A nobody’s son went to the East to work in construction. I was determined to go to France because I had the French language tool.”

© DJ Lucky

© DJ Lucky

Musical references

From semba as resistance to colonialism, by Jovens do Prenda and N’gola Ritmos. From the electronic experiments made by Vum Vum, in the 60s, which Lucky only got to know in Lisbon later on. When I ask him for references of Angolan musicians, the names of Carlos Lamartine, Artur Nunes, Waldemar Bastos, Carlitos Vieira Dias spring to mind, not forgetting the Mingas brothers (André and Ruy), Carlos Burity, Elias Diakimuezo, David Zé, Bonga, etc.

“Our music will always be our music. The generation of the 80s was a bit tired of semba, but now it has recovered. You could hear Gilberto Gil a lot, for example, who performed there several times. But the big bosses in all this were the Kassavs. They changed the image of music. Paulo Flores and Eduardo Paim were the heroes, the pioneers who started to build something new. They brought together semba and the influence of Martinique, and that’s what gave them kizomba. Another rhythm different from semba and zouk, which in the end is zouk love. A mystique and a mishap were created there”.

Of African sounds that passed in Angola, he mentions the music Mario, by Makiadi Luambo Franco, the father of Congolese music, as well as the hits of Fela Kuti, from Nigeria or Manu Dibango, from Cameroon, África Negra, from São Tomé and Príncipe. “It was pan-Africanism in full force,” and Lucky knew what was being produced abroad, especially in rock from the United States and England, he listened to U2, Fine Young Canibals, and enjoyed the whole English scene. He lived through the cassette fever, “we used to take tape recorders and rewind the cassettes with a pen”, from Walkman and Bravo magazine. But “we never left our culture behind. We tried to mix everything, and we were always doing new things. A style of dance didn’t stay for long because something new was created. It’s the creativity of the Angolan. When Kuduro conquers the world, it is due to an immense previous history.”

Arrival in Portugal in 1991

He doesn’t remember the day of the week, but it was cold when his uncle and his brother went to pick him up at the airport. “The brother after me came before, he played at the Primeiro de Agosto club and came to study and work. I was supposed to come to study too, but I wasn’t even sure what to say to get them to let me through. As he came here a lot, my father advised me to say that I was coming to work. He would say, ‘There’s a lot of talk about the European Union, the European zone is going to be unified, and you’re sure to make it to France, but it will take time.’

It was a question of getting somewhere easier and then moving on. That was the plan, but from Angola, the perception differs from when you arrive in Europe, especially Portugal. Lucky says that those who welcomed new arrivals from Portuguese-speaking African countries, especially Angolans, were the Cape Verdeans living on Lisbon’s outskirts. “There were no black people in the centre of Lisbon, only that community of São Bento, of the morna, etc. But most people were in the peripheries: Cova da Moura, Pontinha, Seixal, Cacém, and so on. I ended up in Cova da Moura”. He brought his traveller’s cheque and a little money in hand. “In my last days in Luanda, I no longer lived in Vila Alice but in Palanca, but even so, it was an old Portuguese building, an organized neighbourhood… In 1991 I arrived in Cova da Moura, under construction, and I thought, ‘but this is Europe?’ I wanted to leave, but how could I come back? I had my uncle and my brother here. I stayed to see what was possible, to look for life. We had to adapt. The Cape Verdean community received us well. There were a few Angolans, all very young.

Without documents, he had to work to pay for the house. He still thought about studying at night and working during the day, but working in construction was hard. The dream of going to France to study ended up not coming true. “We entered a reality where only music and socializing helped us cope.” The European Community sent money to build roads and infrastructure, and the Portuguese didn’t want to work on the construction sites. In Cova da Moura there were many bricklayers, a few Cape Verdean bosses or intermediaries who talked to companies to recruit people, such as Teixeira Duarte, where he worked making false ceilings until 1994. He helped build places of culture such as Culturgest, the Centro Cultural de Belém, and the Caixa Geral de Depósitos in Baixa. During the construction boom at Expo 98 and the extraordinary immigrant regulations, Lucky was already working in music, his passion.

© DJ Lucky

© DJ Lucky

Afro nights in Lisbon

When I got homesick, I’d head for African clubs like Kandando and Wifi. “They were a mix between Cape Verde, Guinea, and Angola. I didn’t know much about Mozambique. I only got to know about marrabenta much later. We also went to the disco matinees, Zona Mais and Crazy Night on Saturday and Sunday. We wanted to integrate, not just stay in that context. We wanted to socialize in some way. So I was in Europe, and in Luanda, I was already organizing parties, etc. Also, our Afro sisters didn’t care for us at all, and we started to have some success with the white girls. We spent money on designer clothes and cowboy boots to impress them.”

Lucky kicks off his life in Lisbon’s nightlife in late 1994 in Bairro Alto. “The cathedral was always Frágil, but it was hard to get in because it was so elite. DJ Johnny at the Três Pastorinhos would toast us with super cool black music: Soul to Soul, Guru Jazz Matazz, Arrested Development.” Lisbon’s nightlife is very linked to the Afro scene, with key figures like Hêrnani, Micas, and Zé da Guiné (from Noites Longas club). It would be interesting to map out this mobilization in the city… The first bar he worked in was Kéops, where “there were two resident DJs, the great Lígia (who died recently), and Nuno, who worked at the Casa da Moeda and was a bass player in a punk rock band. They liked my looks. They needed someone to work in the room, to collect the glasses when the bar was full, and ask the customers if they wanted more to drink. Then Nuno realized I was interested in music, I liked Acid Jazz, Jamiroquai, and Urban Species”. And he invited him to try his hand at putting on music. They proposed to Alex, the owner, starting with weak nights (Monday and Sunday), with Nuno’s records. They said: “The kid’s got a knack. Before I knew it I was already in other bars, like Café Suave or California. Then I became a resident at Café Suave”, with the help of Zezé, nicknamed “Saquinhos” (he used to make craftwork) aka Cônego de Braga (lately he’s been playing at the Crew Hassan), who proposed he play at Café Suave, where he used to work.

He ventured as a DJ in 1996. Lisbon dances with Acid house, drum bass, and trip-hop begin to appear, and the figure of the DJ becomes more professional, each with his style and recognition. In his opinion, the DJ culture started in the bars and a lot in Bairro Alto with Africans who made and make the Lisbon night and helped each other. Lucky recalls, “Angola has been here for a long time. If you look at it, this is very much Africa”. Several Afro DJs were trying to introduce African music, but it wasn’t fully accepted. In the beginning, when he played more Afro music, they’d tell him - “Look, we’re not in Amadora, play one or two songs. But black American music was played all the time. “Funk and soul blues heritage from the United States. It was universal music. Now our Africanised songs, which nowadays even white DJs and everybody else plays, before you couldn’t hear, but we tried to introduce them.”

AfroBlues Djs Quartet, with Johny, Lady Brown, Lucky, and João Gomes

“In 2000, the four of us met when things were more open. Johny came with that name, João Gomes, from Cool Hipnoise, and then Space Boys, brought Mozambique, and I brought the Angola and Congo scenes. Lady Brown, a superpower woman, coming up. What if we made a something here? - we thought. Afroblues Djs, it became our name, a mythical photo on Facebook. We started at Bicaense on Tuesdays, two by two, sometimes three or all four, and we did a few years there. The idea was to take African music from the deepest roots to the deepest electronic.”

And in 2005 Buraka Som Sistema emerges. “I lived with Kalaf in front of Dona Mento, a Cape Verdean restaurant in São Cristóvão, on Costa Castelo. Kalaf had to throw a shout here. He was always writing, listening to Lauryn Hill.” Before Buraka, João Barbosa, Branko, and Kalaf did the One Uik project. It was a big event and legitimizes a lot of what came from behind, from those who worked on that fusion. Another milestone is África Festival, produced by Paula Nascimento in three editions: 2005/06/07, a great celebration of the African community in Lisbon and its surroundings, for Lucky “a nice junction of music, theatre, and other arts. It was through this Festival that Lisbon met Ali Farkature, Tumani Diabaté, Zap Mama, and so much more. I miss it many times. I am proud to have been part of the Africa Festival.”

Those were still the days of the Enchufada label, which launched Buraka. There was the Cool Train Crew, which included Johnny, Dinis, Rui Murca, Victor Belanciano, Nuno Rosa, and Tiago Miranda.

© DJ Lucky

© DJ Lucky

An ever-growing musical culture

Lucky worked at a Virgin music store between 1998 and 2000, in Restauradores, where his “musical culture grew a lot. A family was created, Melo D. also worked there, he was in Cool Hipnose and Family, a hip-hop tuga group from the 90s, and after went solo. He was in the jazz section, and I was in soul and dance. We’d get amazing records, and we would get staff discount. I started to get into the cult of vinyl.” And then, he worked at Valentim de Carvalho for two months and quit… “I was tired of retail, and also because I got an offer to program Fluid.”

He came to wish to be a musician and play the bass, but taking lessons was too expensive, and with two jobs, music shops by day, and playing music at night, he had no time left. The spirit of a collector and archivist began to settle, which helped him get into radio and a career as a DJ. And he’s already had a career spanning almost 25 years.

To the question about the worst side of this DJ life and nights out, Lucky answers that the hardest thing is to handle the pressure, and resist alcohol and drugs. “That’s the first danger. I fell into that myself. I overdid it and started losing work. There was a culture of drinking shots, in any bar, the way to say “Hi, good evening, how’s it going?” was with a shot on top. We were young, we started to discover drinking, and new stuff was always coming out, I don’t know how many Vodkas Absoluts…” We agree that you must be very disciplined to make it through the night. “You can get hearing problems, voice problems, with the extra decibels. Fortunately, I balanced it with yoga and went 14 years without drinking. I’ve always been one to get little sleep, I don’t know if it’s because of the anxiety. But I protect myself, and I disappear from the circuit occasionally. I go to an area where I can be quiet without anything, to charge the battery.”

But being a DJ “is not a job in which you just want to be professional and cold”. A DJ stirs emotions, he is a God who is there in the moment, who is asked to keep the night’s euphoria going. “Nowadays, there is a lot of talk about the DJ’s stance. Some are cold and mechanical, they’re there, they’re tough. I came from the leisure DJ culture. I started playing music in bars, and I had to get people dancing every now and then. But my scene has always been more chill out. You have to read people, understand the moment, the cadence in which they’re grooving. You have to learn to play the right cards.” Lucky also enjoys playing music in public spaces, terraces, and gardens for the family component. “People take their little ones and come up to you. For example, the kids come from school on a flea market day in the Botto Machado garden, in Clara Clara kiosk, and the neighbor chats with me, I like it a lot. But I also like music for leisure, that’s why I’ve participated in Out Jazz since the third edition, my music fits very well in the project. But when it’s for clubbing, it’s for clubbing.” And he just went to Lux to play music.

The beginning of plastic arts

He has always been connected to the arts, especially photography. “I used to live with the guys that studied at Arco, we had a darkroom at home, and I modelled, sometimes in clothes with lights. Photography started to interest me a lot. I photographed a lot when I travelled, then the Lomo appeared, and slides. I used film rolls that were out of date, which gave a different contrast. Sometimes I didn’t even develop on film. I just did contact proofs, I liked the challenge of framing. It coincided with my process of quitting alcohol, and it was a motivation. I even made an installation of slides with myself talking into the microphone. When digital came in, I lost my way a bit and photography took a back seat.”

And how does the obsession with collecting clothes pegs come about 16 years ago? “In every town, I’d find a peg. They’d come to me. I became an accumulator or collector. I thought I would do something when I reached 1000 pegs.” The pegs were piling up in different sizes, colors, and models, and with so many pegs piled up, it was already too much (we’re talking about 2300 springs). In conversation with a friend, she tells him – If you have so many pegs and don’t know what to do with them, you can make a clothesline. “When I heard clothesline, I thought of the clotheslines in Costa Castelo, where I take my daughter to school, those old clotheslines from the working-class neighborhoods, with poles and strings. And so I conceived the project for Santa Clara Park for my vinyl collection, with pictures in the trees and a sound base where people had to sit and listen. They would see the photos and listen to a playlist of mine playing. I had to go back to the roots.” This was before the “Kokawusa” project.

Article originally published by World African Artists United at 11/11/2022