No seu acto final, Complô não poupa socos, mas vai com luvas de lã. De volta ao estúdio –– esse refúgio improvisado entre blocos de prédios algures na Margem Sul – pressentimos a mudança de tom. A raiva dá lugar à ternura, talvez porque a ternura sejá mais poderosa. Ghoya grava uma faixa para a companheira. A sua voz abranda, amacia. “Baby, nós merecíamos um filme,” ele diz.

No seu acto final, Complô não poupa socos, mas vai com luvas de lã. De volta ao estúdio –– esse refúgio improvisado entre blocos de prédios algures na Margem Sul – pressentimos a mudança de tom. A raiva dá lugar à ternura, talvez porque a ternura sejá mais poderosa. Ghoya grava uma faixa para a companheira. A sua voz abranda, amacia. “Baby, nós merecíamos um filme,” ele diz.

Afroscreen

02.11.2025 | by Pedro José-Marcellino aka P.J. Marcellino

Balanced between various cultures, he has lived for 31 years in a more open and diverse Lisbon, an openness and diversity to which people like Lucky have contributed so much, from building the city to making the city dance.

This is a city of hard times, but also of encounters and possibilities with which he has grown up. In this text, we are led by the memories of Dj Lucky, between various sound tracks of quisange, semba, and afro blues, and multiple tracks on the floor, from Kinshasa to the Graça neighborhood, passing through Luanda, Cova da Moura, and Bairro Alto.

Balanced between various cultures, he has lived for 31 years in a more open and diverse Lisbon, an openness and diversity to which people like Lucky have contributed so much, from building the city to making the city dance.

This is a city of hard times, but also of encounters and possibilities with which he has grown up. In this text, we are led by the memories of Dj Lucky, between various sound tracks of quisange, semba, and afro blues, and multiple tracks on the floor, from Kinshasa to the Graça neighborhood, passing through Luanda, Cova da Moura, and Bairro Alto.

Face to face

15.11.2022 | by Marta Lança

Notorious for blending the political and profane, denounced for its roots in Vodou, rabòday music is the defiant — and wildly popular — sound of a new, disaffected generation of Haitians. As the country prepares for long-awaited elections starting in August, stars of the genre have become unusually influential by turning public anxieties into dance-friendly anthems.

Notorious for blending the political and profane, denounced for its roots in Vodou, rabòday music is the defiant — and wildly popular — sound of a new, disaffected generation of Haitians. As the country prepares for long-awaited elections starting in August, stars of the genre have become unusually influential by turning public anxieties into dance-friendly anthems.

Stages

28.01.2022 | by Susana Ferreira

How a music shaped by slavery, epidemics, famine and mass migration travelled the world, narrating stories of suffering and resistance. Over time, morna, also known as “música rainha” (“queen music”), underwent several changes to its melodic and rhythmic characteristics, becoming the slower, more mournful version heard today. Characterised by three dimensions of melody, poetry and dance, morna is often sung in Kriolu, Portuguese-based Creole, though it can be instrumental, too.

How a music shaped by slavery, epidemics, famine and mass migration travelled the world, narrating stories of suffering and resistance. Over time, morna, also known as “música rainha” (“queen music”), underwent several changes to its melodic and rhythmic characteristics, becoming the slower, more mournful version heard today. Characterised by three dimensions of melody, poetry and dance, morna is often sung in Kriolu, Portuguese-based Creole, though it can be instrumental, too.

Stages

26.05.2021 | by Beatriz Ramalho da Silva

Lovers rock helped to change perceptions of black music in the British media. Despite its transnational origin, it is considered a distinctly British genre, the first post-colonial music genre to emerge in the UK, before other internationally known genres such as Brit Funk, Acid House, Jungle, UK garage, Dubstep, Grime, or UK drill came about.

Lovers rock helped to change perceptions of black music in the British media. Despite its transnational origin, it is considered a distinctly British genre, the first post-colonial music genre to emerge in the UK, before other internationally known genres such as Brit Funk, Acid House, Jungle, UK garage, Dubstep, Grime, or UK drill came about.

Afroscreen

07.02.2021 | by Marcos Cardão

The relevance of black participation in Portugal in the most diverse areas - including music - dates back several hundred years, but is rarely articulated in dominant public narratives. It is not, of course, that blacks in Portugal have no voice or are not present in the daily life of the country. It's often about talking without being considered, seeing without being seen, singing without being listened to - at least outside a cultural sphere that tends to be more circumscribed.

The relevance of black participation in Portugal in the most diverse areas - including music - dates back several hundred years, but is rarely articulated in dominant public narratives. It is not, of course, that blacks in Portugal have no voice or are not present in the daily life of the country. It's often about talking without being considered, seeing without being seen, singing without being listened to - at least outside a cultural sphere that tends to be more circumscribed.

Stages

01.02.2021 | by Inês Nascimento Rodrigues

The stage and the auditorium are darkened. Suddenly a noise of clinking glasses in the audience is to hear. The stage light is slowly moved in, it remains dimmed considerably. The room is bare, dark and corresponds to a black box theatre. One can see a mountain of white cups on the right half of the stage.

The stage and the auditorium are darkened. Suddenly a noise of clinking glasses in the audience is to hear. The stage light is slowly moved in, it remains dimmed considerably. The room is bare, dark and corresponds to a black box theatre. One can see a mountain of white cups on the right half of the stage.

Stages

20.10.2011 | by Grit Köppen

The solo violin playing of Isaac Molelekoa is so impressive, melancholic and space pervading that the viewers are dispelled. Extremely slow a dancer becomes visible, who stands in a narrow cone of light in the center of the stage. It is a quiet, strong and contrastive picture - this disturbing music of the violinist, that encourages you to move either internally or externally, and the continued structural integrity of the dancer Maqoma on stage.

The solo violin playing of Isaac Molelekoa is so impressive, melancholic and space pervading that the viewers are dispelled. Extremely slow a dancer becomes visible, who stands in a narrow cone of light in the center of the stage. It is a quiet, strong and contrastive picture - this disturbing music of the violinist, that encourages you to move either internally or externally, and the continued structural integrity of the dancer Maqoma on stage.

Stages

22.09.2011 | by Grit Köppen

For four days last month, tens of thousands of fans from around the world descended on Essaouira, Morocco, for an African musical extravaganza: the annual festival Gnaoua et Musiques du Monde, now in its 14th edition. The protagonist of this musical feast was as usual Gnawa music: when to Gnawa masters like Mustapha Baqbou, Mohammed Guinea, and Hassan Boussou were not on the main public stages, they were performing lilas (night of healing) that began at midnight at different riads (traditional style Moorish house with a courtyard); and that is where true European aficionados went to trance and to learn the specifics of daqa marrakchiya (the percussive clap associated with the city of Marrakesh).

For four days last month, tens of thousands of fans from around the world descended on Essaouira, Morocco, for an African musical extravaganza: the annual festival Gnaoua et Musiques du Monde, now in its 14th edition. The protagonist of this musical feast was as usual Gnawa music: when to Gnawa masters like Mustapha Baqbou, Mohammed Guinea, and Hassan Boussou were not on the main public stages, they were performing lilas (night of healing) that began at midnight at different riads (traditional style Moorish house with a courtyard); and that is where true European aficionados went to trance and to learn the specifics of daqa marrakchiya (the percussive clap associated with the city of Marrakesh).

I'll visit

22.07.2011 | by Jorge de La Barre

This paper explores Lisbon’s contemporary music scenes within the perspective of music and cultural circulation. It discusses the various ways in which music and cities interact, in a context of increased inter-connectedness between the local and the global. It suggests that music creation and performance (and more broadly, cultural innovation), cannot be reduced to neither grassroots nor institutional initiatives. On the premises of the existence of a so-called “global culture”, cities tend to reinvent themselves by promoting various (and eventually competing) self-definitions. In the case of Lisbon, this tendency is accompanied by a seemingly increased desire to connect (or re-connect) with the Lusophone world, eventually informing Lisbon’s self-images as an inclusive and multicultural city. In this process, new forms of ethnicity may gain visibility in the marketing of Luso-World music (or World music as practiced in the Portuguese-speaking countries). At the horizon of imagined cities as “transcultural megacities”, music tends to gain agency in the promotion of senses of place and belonging in, and to the city.

This paper explores Lisbon’s contemporary music scenes within the perspective of music and cultural circulation. It discusses the various ways in which music and cities interact, in a context of increased inter-connectedness between the local and the global. It suggests that music creation and performance (and more broadly, cultural innovation), cannot be reduced to neither grassroots nor institutional initiatives. On the premises of the existence of a so-called “global culture”, cities tend to reinvent themselves by promoting various (and eventually competing) self-definitions. In the case of Lisbon, this tendency is accompanied by a seemingly increased desire to connect (or re-connect) with the Lusophone world, eventually informing Lisbon’s self-images as an inclusive and multicultural city. In this process, new forms of ethnicity may gain visibility in the marketing of Luso-World music (or World music as practiced in the Portuguese-speaking countries). At the horizon of imagined cities as “transcultural megacities”, music tends to gain agency in the promotion of senses of place and belonging in, and to the city.

City

18.05.2011 | by Jorge de La Barre

Even today, an analysis of the complex role of music in film is often forgotten by critics, many of whom remain prostrate before the dictatorship of the image. Yet as a manifestation of culture, music has a privileged position with respect to the study of representations of identity and ideology; moreover, in its subversive and dialogic aspects, it can reveal significant directorial decisions related to dynamics of power and exclusion.

Even today, an analysis of the complex role of music in film is often forgotten by critics, many of whom remain prostrate before the dictatorship of the image. Yet as a manifestation of culture, music has a privileged position with respect to the study of representations of identity and ideology; moreover, in its subversive and dialogic aspects, it can reveal significant directorial decisions related to dynamics of power and exclusion.

Afroscreen

16.05.2011 | by Beatriz Leal Riesco

Musseque residents would likely have said, “my suffering, yes, but ours as well.”

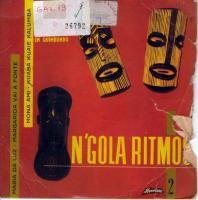

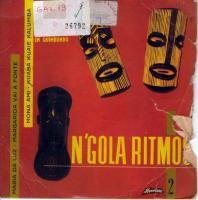

Music, in late colonial Angola took private grief and by performing it publicly made it collective. The sound, and perhaps even the process, was attractive to whites as well and in an ironic twist on the lusotropical narrative, by the early 1970s, whites made their way to the musseques in sizeable numbers to hear Ngola Ritmos and other popular bands play.

Musseque residents would likely have said, “my suffering, yes, but ours as well.”

Music, in late colonial Angola took private grief and by performing it publicly made it collective. The sound, and perhaps even the process, was attractive to whites as well and in an ironic twist on the lusotropical narrative, by the early 1970s, whites made their way to the musseques in sizeable numbers to hear Ngola Ritmos and other popular bands play.

Stages

01.09.2010 | by Marissa Moorman

Her compositions were first known only in a small inner circle, but with the Luanda Song Festival, her work became known to a wider public. In the 60s she had formed a duo with the Portuguese journalist Adelino Tavares da Silva, who had just arrived in Angola. They composed four or five songs together and then registered in the Portuguese Writers’ Association, with Adelino as songwriter and Ana Maria as composer. It can be said that the duo revolutionised the Song Festival, when Maria Provocação was performed by Sara Chaves and Mulata é a Noite by Concha de Mascarenhas. They were both accompanied by Ngola Ritmos, the Angolan rhythm group.

Her compositions were first known only in a small inner circle, but with the Luanda Song Festival, her work became known to a wider public. In the 60s she had formed a duo with the Portuguese journalist Adelino Tavares da Silva, who had just arrived in Angola. They composed four or five songs together and then registered in the Portuguese Writers’ Association, with Adelino as songwriter and Ana Maria as composer. It can be said that the duo revolutionised the Song Festival, when Maria Provocação was performed by Sara Chaves and Mulata é a Noite by Concha de Mascarenhas. They were both accompanied by Ngola Ritmos, the Angolan rhythm group.

Stages

08.07.2010 | by Mário Rui Silva

No seu acto final, Complô não poupa socos, mas vai com luvas de lã. De volta ao estúdio –– esse refúgio improvisado entre blocos de prédios algures na Margem Sul – pressentimos a mudança de tom. A raiva dá lugar à ternura, talvez porque a ternura sejá mais poderosa. Ghoya grava uma faixa para a companheira. A sua voz abranda, amacia. “Baby, nós merecíamos um filme,” ele diz.

No seu acto final, Complô não poupa socos, mas vai com luvas de lã. De volta ao estúdio –– esse refúgio improvisado entre blocos de prédios algures na Margem Sul – pressentimos a mudança de tom. A raiva dá lugar à ternura, talvez porque a ternura sejá mais poderosa. Ghoya grava uma faixa para a companheira. A sua voz abranda, amacia. “Baby, nós merecíamos um filme,” ele diz.  Balanced between various cultures, he has lived for 31 years in a more open and diverse Lisbon, an openness and diversity to which people like Lucky have contributed so much, from building the city to making the city dance.

This is a city of hard times, but also of encounters and possibilities with which he has grown up. In this text, we are led by the memories of Dj Lucky, between various sound tracks of quisange, semba, and afro blues, and multiple tracks on the floor, from Kinshasa to the Graça neighborhood, passing through Luanda, Cova da Moura, and Bairro Alto.

Balanced between various cultures, he has lived for 31 years in a more open and diverse Lisbon, an openness and diversity to which people like Lucky have contributed so much, from building the city to making the city dance.

This is a city of hard times, but also of encounters and possibilities with which he has grown up. In this text, we are led by the memories of Dj Lucky, between various sound tracks of quisange, semba, and afro blues, and multiple tracks on the floor, from Kinshasa to the Graça neighborhood, passing through Luanda, Cova da Moura, and Bairro Alto.  Notorious for blending the political and profane, denounced for its roots in Vodou, rabòday music is the defiant — and wildly popular — sound of a new, disaffected generation of Haitians. As the country prepares for long-awaited elections starting in August, stars of the genre have become unusually influential by turning public anxieties into dance-friendly anthems.

Notorious for blending the political and profane, denounced for its roots in Vodou, rabòday music is the defiant — and wildly popular — sound of a new, disaffected generation of Haitians. As the country prepares for long-awaited elections starting in August, stars of the genre have become unusually influential by turning public anxieties into dance-friendly anthems.  How a music shaped by slavery, epidemics, famine and mass migration travelled the world, narrating stories of suffering and resistance. Over time, morna, also known as “música rainha” (“queen music”), underwent several changes to its melodic and rhythmic characteristics, becoming the slower, more mournful version heard today. Characterised by three dimensions of melody, poetry and dance, morna is often sung in Kriolu, Portuguese-based Creole, though it can be instrumental, too.

How a music shaped by slavery, epidemics, famine and mass migration travelled the world, narrating stories of suffering and resistance. Over time, morna, also known as “música rainha” (“queen music”), underwent several changes to its melodic and rhythmic characteristics, becoming the slower, more mournful version heard today. Characterised by three dimensions of melody, poetry and dance, morna is often sung in Kriolu, Portuguese-based Creole, though it can be instrumental, too.  Lovers rock helped to change perceptions of black music in the British media. Despite its transnational origin, it is considered a distinctly British genre, the first post-colonial music genre to emerge in the UK, before other internationally known genres such as Brit Funk, Acid House, Jungle, UK garage, Dubstep, Grime, or UK drill came about.

Lovers rock helped to change perceptions of black music in the British media. Despite its transnational origin, it is considered a distinctly British genre, the first post-colonial music genre to emerge in the UK, before other internationally known genres such as Brit Funk, Acid House, Jungle, UK garage, Dubstep, Grime, or UK drill came about.  The relevance of black participation in Portugal in the most diverse areas - including music - dates back several hundred years, but is rarely articulated in dominant public narratives. It is not, of course, that blacks in Portugal have no voice or are not present in the daily life of the country. It's often about talking without being considered, seeing without being seen, singing without being listened to - at least outside a cultural sphere that tends to be more circumscribed.

The relevance of black participation in Portugal in the most diverse areas - including music - dates back several hundred years, but is rarely articulated in dominant public narratives. It is not, of course, that blacks in Portugal have no voice or are not present in the daily life of the country. It's often about talking without being considered, seeing without being seen, singing without being listened to - at least outside a cultural sphere that tends to be more circumscribed.  The stage and the auditorium are darkened. Suddenly a noise of clinking glasses in the audience is to hear. The stage light is slowly moved in, it remains dimmed considerably. The room is bare, dark and corresponds to a black box theatre. One can see a mountain of white cups on the right half of the stage.

The stage and the auditorium are darkened. Suddenly a noise of clinking glasses in the audience is to hear. The stage light is slowly moved in, it remains dimmed considerably. The room is bare, dark and corresponds to a black box theatre. One can see a mountain of white cups on the right half of the stage.  The solo violin playing of Isaac Molelekoa is so impressive, melancholic and space pervading that the viewers are dispelled. Extremely slow a dancer becomes visible, who stands in a narrow cone of light in the center of the stage. It is a quiet, strong and contrastive picture - this disturbing music of the violinist, that encourages you to move either internally or externally, and the continued structural integrity of the dancer Maqoma on stage.

The solo violin playing of Isaac Molelekoa is so impressive, melancholic and space pervading that the viewers are dispelled. Extremely slow a dancer becomes visible, who stands in a narrow cone of light in the center of the stage. It is a quiet, strong and contrastive picture - this disturbing music of the violinist, that encourages you to move either internally or externally, and the continued structural integrity of the dancer Maqoma on stage.  For four days last month, tens of thousands of fans from around the world descended on Essaouira, Morocco, for an African musical extravaganza: the annual festival Gnaoua et Musiques du Monde, now in its 14th edition. The protagonist of this musical feast was as usual Gnawa music: when to Gnawa masters like Mustapha Baqbou, Mohammed Guinea, and Hassan Boussou were not on the main public stages, they were performing lilas (night of healing) that began at midnight at different riads (traditional style Moorish house with a courtyard); and that is where true European aficionados went to trance and to learn the specifics of daqa marrakchiya (the percussive clap associated with the city of Marrakesh).

For four days last month, tens of thousands of fans from around the world descended on Essaouira, Morocco, for an African musical extravaganza: the annual festival Gnaoua et Musiques du Monde, now in its 14th edition. The protagonist of this musical feast was as usual Gnawa music: when to Gnawa masters like Mustapha Baqbou, Mohammed Guinea, and Hassan Boussou were not on the main public stages, they were performing lilas (night of healing) that began at midnight at different riads (traditional style Moorish house with a courtyard); and that is where true European aficionados went to trance and to learn the specifics of daqa marrakchiya (the percussive clap associated with the city of Marrakesh).  This paper explores Lisbon’s contemporary music scenes within the perspective of music and cultural circulation. It discusses the various ways in which music and cities interact, in a context of increased inter-connectedness between the local and the global. It suggests that music creation and performance (and more broadly, cultural innovation), cannot be reduced to neither grassroots nor institutional initiatives. On the premises of the existence of a so-called “global culture”, cities tend to reinvent themselves by promoting various (and eventually competing) self-definitions. In the case of Lisbon, this tendency is accompanied by a seemingly increased desire to connect (or re-connect) with the Lusophone world, eventually informing Lisbon’s self-images as an inclusive and multicultural city. In this process, new forms of ethnicity may gain visibility in the marketing of Luso-World music (or World music as practiced in the Portuguese-speaking countries). At the horizon of imagined cities as “transcultural megacities”, music tends to gain agency in the promotion of senses of place and belonging in, and to the city.

This paper explores Lisbon’s contemporary music scenes within the perspective of music and cultural circulation. It discusses the various ways in which music and cities interact, in a context of increased inter-connectedness between the local and the global. It suggests that music creation and performance (and more broadly, cultural innovation), cannot be reduced to neither grassroots nor institutional initiatives. On the premises of the existence of a so-called “global culture”, cities tend to reinvent themselves by promoting various (and eventually competing) self-definitions. In the case of Lisbon, this tendency is accompanied by a seemingly increased desire to connect (or re-connect) with the Lusophone world, eventually informing Lisbon’s self-images as an inclusive and multicultural city. In this process, new forms of ethnicity may gain visibility in the marketing of Luso-World music (or World music as practiced in the Portuguese-speaking countries). At the horizon of imagined cities as “transcultural megacities”, music tends to gain agency in the promotion of senses of place and belonging in, and to the city.  Even today, an analysis of the complex role of music in film is often forgotten by critics, many of whom remain prostrate before the dictatorship of the image. Yet as a manifestation of culture, music has a privileged position with respect to the study of representations of identity and ideology; moreover, in its subversive and dialogic aspects, it can reveal significant directorial decisions related to dynamics of power and exclusion.

Even today, an analysis of the complex role of music in film is often forgotten by critics, many of whom remain prostrate before the dictatorship of the image. Yet as a manifestation of culture, music has a privileged position with respect to the study of representations of identity and ideology; moreover, in its subversive and dialogic aspects, it can reveal significant directorial decisions related to dynamics of power and exclusion.  Musseque residents would likely have said, “my suffering, yes, but ours as well.”

Music, in late colonial Angola took private grief and by performing it publicly made it collective. The sound, and perhaps even the process, was attractive to whites as well and in an ironic twist on the lusotropical narrative, by the early 1970s, whites made their way to the musseques in sizeable numbers to hear Ngola Ritmos and other popular bands play.

Musseque residents would likely have said, “my suffering, yes, but ours as well.”

Music, in late colonial Angola took private grief and by performing it publicly made it collective. The sound, and perhaps even the process, was attractive to whites as well and in an ironic twist on the lusotropical narrative, by the early 1970s, whites made their way to the musseques in sizeable numbers to hear Ngola Ritmos and other popular bands play.  Her compositions were first known only in a small inner circle, but with the Luanda Song Festival, her work became known to a wider public. In the 60s she had formed a duo with the Portuguese journalist Adelino Tavares da Silva, who had just arrived in Angola. They composed four or five songs together and then registered in the Portuguese Writers’ Association, with Adelino as songwriter and Ana Maria as composer. It can be said that the duo revolutionised the Song Festival, when Maria Provocação was performed by Sara Chaves and Mulata é a Noite by Concha de Mascarenhas. They were both accompanied by Ngola Ritmos, the Angolan rhythm group.

Her compositions were first known only in a small inner circle, but with the Luanda Song Festival, her work became known to a wider public. In the 60s she had formed a duo with the Portuguese journalist Adelino Tavares da Silva, who had just arrived in Angola. They composed four or five songs together and then registered in the Portuguese Writers’ Association, with Adelino as songwriter and Ana Maria as composer. It can be said that the duo revolutionised the Song Festival, when Maria Provocação was performed by Sara Chaves and Mulata é a Noite by Concha de Mascarenhas. They were both accompanied by Ngola Ritmos, the Angolan rhythm group.