Music and Lusotropicalism in Late Colonial Luanda

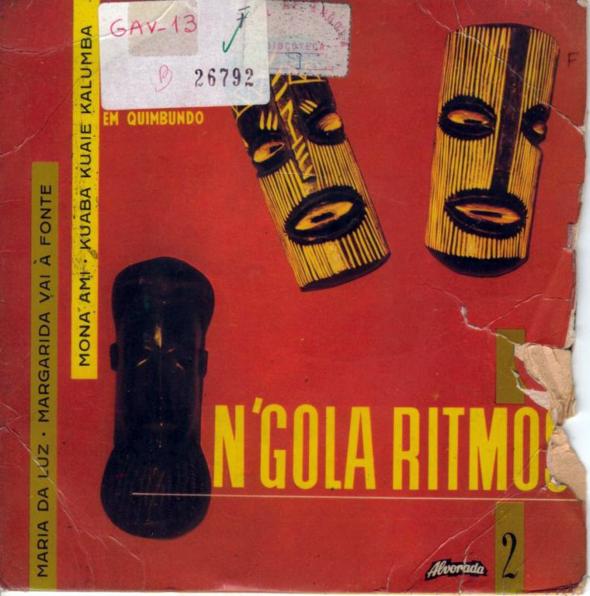

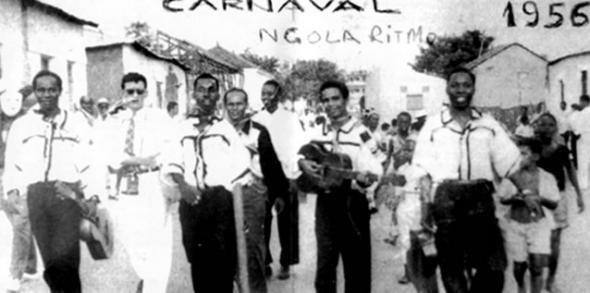

In the mid 1950s, the band Ngola Ritmos performed at the Teatro Nacional (National Theater) in Luanda’s baixa. The venue’s name referred, of course, to the Portuguese that nation embraced Angola as an overseas territory. This was not custodial colonialism but fierce possession dressed up in lusotropicalist discourse. Angolan ‘folklore,’ which Ngola Ritmos represented, served to encapsulate and perform difference, making quaint what was potentially explosive cultural difference. The Portuguese nation would subsume Angolan specificity in a demonstration of the Portuguese skill at adapting to the tropics. Yet when Ngola Ritmos sang that night at the Teatro Nacional the emcee re-inscribed the divide between musseque and baixa, African and Portuguese, thus disrobing the lusotropicalist fantasy.

When the emcee presented the band he also announced the names of the songs they were going to sing. He read the translations of song names into Portuguese from Kimbundu, with which he had been provided1. Zé Maria dos Santos of Ngola Ritmos recounted the event: “we had a song that was called ‘Ngongo Jami.’ At that time we called it ‘Ngongo Jami’ – my suffering – and the emcee said, ‘well, not my suffering, theirs’ – when he presented us. But just like that: ‘not mine, theirs.’”2 Zé Maria was obviously offended by the emcee’s condescending attitude. And the emcee’s gaff baldly expressed the racism, economic deprivation and absence of political representation or rights that most Angolans living in the musseques keenly felt. Musseque residents would likely have said, “my suffering, yes, but ours as well.”

When the emcee presented the band he also announced the names of the songs they were going to sing. He read the translations of song names into Portuguese from Kimbundu, with which he had been provided1. Zé Maria dos Santos of Ngola Ritmos recounted the event: “we had a song that was called ‘Ngongo Jami.’ At that time we called it ‘Ngongo Jami’ – my suffering – and the emcee said, ‘well, not my suffering, theirs’ – when he presented us. But just like that: ‘not mine, theirs.’”2 Zé Maria was obviously offended by the emcee’s condescending attitude. And the emcee’s gaff baldly expressed the racism, economic deprivation and absence of political representation or rights that most Angolans living in the musseques keenly felt. Musseque residents would likely have said, “my suffering, yes, but ours as well.”

Music, in late colonial Angola took private grief and by performing it publicly made it collective. The sound, and perhaps even the process, was attractive to whites as well and in an ironic twist on the lusotropical narrative, by the early 1970s, whites made their way to the musseques in sizeable numbers to hear Ngola Ritmos and other popular bands play.3 In the end, it was Angolan music and Africans who succeeded at producing a culture, both cosmopolitan and African, that attracted European audiences.

As the anecdote above reveals, context and location shape the interpretation of music. Musical lyrics were just one of the elements of music that Angolans living in the musseques and throughout the country found so compelling. Between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s, song writers and musicians explored the limitations of life under colonial rule while making people dance.

As the anecdote above reveals, context and location shape the interpretation of music. Musical lyrics were just one of the elements of music that Angolans living in the musseques and throughout the country found so compelling. Between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s, song writers and musicians explored the limitations of life under colonial rule while making people dance.

In my interviews and conversations with Angolans, time and again I was told that what occupied peoples attentions in the late colonial period were day-to-day concerns: social and familial relations, getting an education, making enough money to feed one’s family, and maintaining one’s dignity under difficult socio-economic conditions. In music, musicians interpreted, re-created and transformed that world. Carlos Pimentel remembered the lyrics in the following terms:

“our music was oriented to the troubles we had, to the suffering we had. But we didn’t play music because we were political, no, but because we lived that reality and we saw that the rest of the people that lived in the musseques lived in bad and squalid conditions [‘mal e porcamente.’] So we sang about our bitterness in Kimbundu and they didn’t know. We even talked badly about them and they didn’t know it!”

Pimentel emphasizes that politics was organic to the situation. For the most part, politically driven musicians did not decide to sing in order to get out a message or make a political statement. Rather, musicians sang about what they knew and what they saw. Under conditions of colonial exploitation that was political because the impediments to people’s aspirations and the hardships they suffered were often created by the colonial state and its lackeys.

Pimentel notes that by singing in Kimbundu, and other local languages, musicians were able to criticize the Portuguese colonial system and its representatives. It was in this sense that music “passed a message” and figured as a site of resistance. But lyrics were not only a way of saying “no,” as Amadeu Amorim a band member of Ngola Ritmos described it.  Lyrics and the music were also about saying “yes”: affirming and producing angolanidade and, in the process, marking out a culturally autonomous space forged and expressed in African owned and operated clubs, in music festivals, in dress and dance and attitude. Lyrics did not simply mirror daily life or nationalist consciousness; they interpreted the former and created the latter. When Teta Lando intoned: “Um assobio meu é pra esquecer as minhas tristezas” (“My whistling is to forget my sadness”), he was echoing more traditional music in style and sound (slow laments which connoted a kind of fatalism), commenting on colonialism (because the Portuguese language in which he sang was that of the colonizer) and inciting nationalist sentiments (as Albina Assis told me when she remembered this song: “everyone knew that the source of his sadness was the murder of his father by the Portuguese.”)

Lyrics and the music were also about saying “yes”: affirming and producing angolanidade and, in the process, marking out a culturally autonomous space forged and expressed in African owned and operated clubs, in music festivals, in dress and dance and attitude. Lyrics did not simply mirror daily life or nationalist consciousness; they interpreted the former and created the latter. When Teta Lando intoned: “Um assobio meu é pra esquecer as minhas tristezas” (“My whistling is to forget my sadness”), he was echoing more traditional music in style and sound (slow laments which connoted a kind of fatalism), commenting on colonialism (because the Portuguese language in which he sang was that of the colonizer) and inciting nationalist sentiments (as Albina Assis told me when she remembered this song: “everyone knew that the source of his sadness was the murder of his father by the Portuguese.”)

Reflecting on daily life, musicians collectivized and transmuted individual suffering and disgrace into public entertainment: pathos became ethos. Songs that contained social critiques targeted both the colonial order and musseque society. Criticisms of drunkenness, indebtedness, and women with loose morals indirectly pointed the finger at colonialism but also denoted struggles over the moral contours of the nascent nation. Since the majority of musicians and composers were young men, their relationships with women often featured in song. Indeed the gendered dynamics of social life in Luanda´s musseques were in part constructed and negotiated in lyrics. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, audiences often heard lyrics that, in praise or in condemnation, talked about women. Loves lost, found, frustrated and sullied were the subject of hundreds of songs. As the song “Chofer de praça” demonstrates, love stories could also contain political critiques. At the same time, the romantic genre was one of the elements of the music’s cosmopolitanism since much of the foreign music that was the fare at parties and on the radio consisted of love songs.4

Songs were sung in a variety of languages: Kimbundu, Kikongo, Umbundu (the languages of the three largest ethnic groups), in Portuguese, or a mixture of Portuguese and Kimbundu and, occasionally, words or lines in French or English or Spanish would appear. Many musicians remembered imitating foreign stars (everything from Otis Redding and James Brown to Charles Aznavour) as a part of their repertoire and musical education, a kind of stepping stone on the way to creating a local sound with international resonance.5 A few rock bands emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s (os Rocks, the 5 Kings, and os Kriptons) but they did not garner the same degree of public acclaim as semba. While music was sung in almost all of the local Angolan languages, Kimbundu was the predominant one. Because Luanda was the colonial capital and the site of the longest and most intense colonial presence, Kimbundu was, for the most part, not spoken by urban elites by the early 20th century.6 In fact, many musicians learned Kimbundu as adults and used it only in song and not in conversation.  Therefore, in Luanda, and indeed throughout Angola, Kimbundu, more than other languages, would have symbolized both life outside the city and the violent denial of African culture by colonial fiat. Kimbundu might have a regional specificity but its negation by the colonial authorities who denigrated it as the ‘language of dogs,’ resonated throughout the territory. The new urban Angolan music became a kind of lingua franca, its sung language less important than the fact that it spoke of a shared culture that was urban, African, cosmopolitan and still vibrating with the rhythms of life and sounds of the rural world.

Therefore, in Luanda, and indeed throughout Angola, Kimbundu, more than other languages, would have symbolized both life outside the city and the violent denial of African culture by colonial fiat. Kimbundu might have a regional specificity but its negation by the colonial authorities who denigrated it as the ‘language of dogs,’ resonated throughout the territory. The new urban Angolan music became a kind of lingua franca, its sung language less important than the fact that it spoke of a shared culture that was urban, African, cosmopolitan and still vibrating with the rhythms of life and sounds of the rural world.

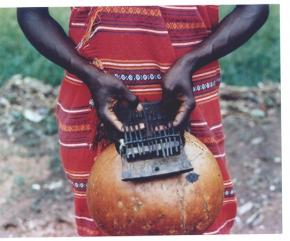

Singing in local languages created a new and different sound. Musicians drew upon a variety of resources in their compositions and performances –fables from different ethnic groups, songs sung in the contexts of wakes and carnival rivalries, Congolese guitar styles, Latin American dance beats, Angolan instruments (like the dikanza and kissange),7 foreign cinema, European and American fashion not to mention their own experiences.8  The implications of this mixing, far from symbolizing a lusotropical creolization, actually stood that notion on its head. Things European (not just Portuguese) and Latin American – instruments, song length, romantic themes, fashions – were used to emphasize things African – local stories, flora and fauna, parables, dances, languages - and to thereby create things Angolan.9 As Jorge Macedo put it when describing the music of Ngola Ritmos and the ensuing style played in the musseques: “Latin-American sounds, the twin of African rhythms, fed a climate of Africanization.” In this way, the divisions instituted through colonial rule between the traditional and the modern, the rural and the urban, the black and the white, the musseque and the baixa, were played on, broken down and re-organized.

The implications of this mixing, far from symbolizing a lusotropical creolization, actually stood that notion on its head. Things European (not just Portuguese) and Latin American – instruments, song length, romantic themes, fashions – were used to emphasize things African – local stories, flora and fauna, parables, dances, languages - and to thereby create things Angolan.9 As Jorge Macedo put it when describing the music of Ngola Ritmos and the ensuing style played in the musseques: “Latin-American sounds, the twin of African rhythms, fed a climate of Africanization.” In this way, the divisions instituted through colonial rule between the traditional and the modern, the rural and the urban, the black and the white, the musseque and the baixa, were played on, broken down and re-organized.

- 1. An article in Anangola’s Jornal de Angola notes that this was the band’s common practice: “Vieira Dias, before each performance by his group, would explain the story of each composition so that everyone would integrate and understand perfectly the melody and the rhythm.” Jornal de Angola, June 19, 1958: 7.

- 2. Interview: Amadeu Amorim and José Maria dos Santos, 4 April 2001, Luanda. Another similar story also circulates in popular memory and symbolizes the utter emptiness of lusotropicalist claims and the small-mindedness of Portuguese settlers. In this story Ngola Ritmos is literally boo-ed off the stage when they sing and are told to “go back to the bush.” This story appears in dos Santos, ABC do Bê Ó, 226 and Silva, “Estórias da Música em Angola (4),” 52 and was repeated by many, many people. Amorim remembered a similar reception among the African elite at the Liga who looked down on the use of Kimbundu. When, in the mid-‘50s, the band sang there Amorim remembered that members of the audience bowed their heads in disapproval. See Foi Há Vinte Anos, interview with Amadeu Amorim by Drumond Jaime and Helder Barber, Rádio Nacional de Angola, 1995.

- 3. Interviews: Manuel Faria, 19 March 2002; Alberto Jaime, 12 December 2001; Carlos Lamartine, 4 September 2001; and António Sebastião “Santocas” Vicente, 26 November 2001, all in Luanda.

- 4. Bob White likewise argues that romantic songs, in the Zairean repertoire of the same period, are a demonstration of cosmopolitanism or “worldliness.” See White, “Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms,” 674.

- 5. On at least two occasions I attended musical events where figures from this generation played and where the main musical fare was European and American music from the 1960s and 1970s. At one of Luanda’s most elite clubs Xavarotti (which was the only place to hear live music when I first went to Angola in 1997), the mike was passed around to various musicians in attendance in the audience. People sang music by Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Roberto Carlos, a famous Brazilian singer, to which audience members sang along. The club’s owner, Mello Xavier, had been in a rock band in the 1960s. Today he is one of Angola’s wealthiest entrepreneurs. Likewise, when Sinatra passed away in 1998, Dioísio Rocha dedicated one of his radio broadcasts to Sinatra’s music and legacy. Many of these folks are the same ones who pioneered and championed semba and its distinctively Angolan sound.

- 6. In earlier periods Kimbundu had actually been the lingua franca of the city, spoken by African, Portuguese and Brazilian residents alike. Many musicians and cultural producers heard Kimbundu around them but they did not grow up speaking it. And Kimbundu was certainly spoken in the city, just not by the elites by the 1940s.

- 7. The kissange is a thumb piano typically constructed with metal strips on a wooden box or base, in Zimbabwe it is called the mbira.

- 8. See Veit Erlmann, African Stars: Studies in Black South African Performance, 174: “the presence of diverse and sometimes heterogeneous symbolic levels through the use of several communicative channels such as dress, choreography, melodic and harmonic structure, and principles of internal group structure enabled migrants to metaphorically define a space in which their survival could best be organized.”

- 9. In this way, Angolan musicians created a cosmopolitan sound. As Turino defines it, cosmopolitan refers to “objects, ideas, and cultural positions that are widely diffused throughout the world and yet are specific only to certain portions of the populations within given countries….[Cosmopolitanism] has to be realized in specific locations and in the lives of actual people. It is thus always localized, and will be shaped by and somewhat distinct in each locale. Cosmopolitan cultural formations are therefore always simultaneously local and translocal.” Turino, Nationalists, Cosmopolitans and Popular Music in Zimbabwe, 7.