How Disaster and Tragedy Spawned a Radical Music Movement in Haiti

Notorious for blending the political and profane, denounced for its roots in Vodou, rabòday music is the defiant — and wildly popular — sound of a new, disaffected generation of Haitians. As the country prepares for long-awaited elections starting in August, stars of the genre have become unusually influential by turning public anxieties into dance-friendly anthems.

PORT-AU-PRINCE — It’s campaign season in Port-au-Prince, and the singer Freshla’s phone has been lighting up for months with calls from senatorial candidates and presidential hopefuls looking for an endorsement. This is standard fare in Haiti, where the country’s better-known musicians are regularly courted by brands and bureaucrats hoping to harness their star power. After four years of delays and aggravating political theater, over 100 political parties have registered for overdue elections staggered over this summer and fall that will fill every office in the country, a staggering 6,000 local, regional, and national government posts in total to be filled. And, as it happens, Freshla has a song that’s tailor-made for the occasion.

“Kite Ti Pati’m Kanpe,” a song released by Freshla and his group Vwadèzil for the 2015 national carnival celebrations, went into heavy rotation around the country following its release in January. The title, a play on words, can be twisted a few different ways, referring either to a political party, a piece of the pie, or a slang term for penis — “let my little part(y) stand.” The song, a ripple of sly jabs at Haitian political dysfunction over rapid-fire drums and keyboard licks, quickly slipped into everyday slang. In the capital’s streets, women and men who were in on the joke began to salute each other with a gleeful “ti pati’m!” My little part!

“It’s about elections and erections,” Freshla told me in Creole one afternoon in his car, cracking a broad grin as he inched us through a typically agonizing Port-au-Prince traffic jam. Cheeky double meanings and metaphors are his trademark. So is rabòday, the new wave of electronic dance music he and a producer named G-Dolph sparked in 2010 following the catastrophic earthquake. In just a few years, rabòday invaded the sound systems of Haiti, blaring from taxi stands, at rowdy basketball tournaments, and dominating street parties that spilled out onto the roads each weekend.

Freshla DJs a rabòday dance party. Marie Arago for BuzzFeed News

Freshla DJs a rabòday dance party. Marie Arago for BuzzFeed News

Definitions can be slippery, but the roots of electronic rabòday can be found in rara, a music older than Haiti itself. It began with the indigenous Taíno people, mixed with rhythms brought from Africa by slaves, and eventually morphed and modernized into a style that today is played by roving musicians throughout the country. Rara bands lead crowds through Haiti’s streets, dancing to handmade bamboo and metal horns and drums that hang heavy on thick shoulder straps. They are called on during protests, for funeral marches, and in religious Vodou service, to play songs that are proud, critical, defiant, and joyful. Drum rhythms have names and contexts, many that can be traced back to the distinct African peoples that fused together to form Haiti, and “rabòday” is the name of one that’s long been favored by these rara bands. In recent years, a new electronic incarnation of rabòday — digitized and crunched with frenetic urgency — exploded to become one of the defining sounds of a young, disaster-surviving generation of Haitians.

As we crawled slowly through the mess of cars closer to a tangled intersection, street boys swarmed Freshla’s car with their washrags, sing-shouting his chorus while whipping away at dust and daily grime. He groaned — he is recognized everywhere he goes — but greeted each boy individually, slapping cash in their cracked hands through the open window. At the gas station and in line for coffee at a bakery, people stopped him for selfies. At a recent birthday party for a former minister of tourism, an older gentleman came up to put his arm around Freshla at the end of the night. “Every year you put out a song that makes me think,” he slurred. “I love you.” At a police checkpoint, grim-faced officers broke into smiles when they saw Freshla behind the wheel, taking a hand off their guns to offer the artist a pound. “Ti pati!” they greeted him. “Are you standing?”

“Standing hard,” Freshla gave his standard reply, and they waved him past the other cars with a laugh.

Born Donald Joseph, these days Freshla is known as the King of Rabòday. It’s a title that was officially bestowed on him last year by the mayor of Delmas, the sprawling section of metropolitan Port-au-Prince where he and G-Dolph reside—and one of the candidates he’s promised to promote so far in next month’s round of local elections. A commemorative plaque hangs on the wall of his one-bedroom apartment, one more in a collection of other music trophies.

Even still, despite rabòday’s ubiquity in Haiti, and despite Freshla’s broad accolades, the genre isn’t universally loved. The harshest jabs against it peel back the curtain on a corrosive ongoing dispute over how to define Haitianness; on one side, those who look down on rara and anything Vodou-related with disdain, and would rather ignore that part of history; on the other, artists and scholars active in preserving Haiti’s African roots, who dismiss this computer-tweaked dance music wave as unlearned noise disrespectful to the ancestors.

From the moment this uniquely Haitian EDM exploded, it’s had to battle the stigma of being low-class, ghetto, a by-product of rubble and disorder. If not for Freshla’s dogged dedication to promote this music, and to draw in more producers and collaborators, the trend might have long fizzled out of fashion.

DJ TonyMix, one of Haiti's most popular DJs and a prominent ambassador for rabòday, at a block party in Port au Prince.

DJ TonyMix, one of Haiti's most popular DJs and a prominent ambassador for rabòday, at a block party in Port au Prince.

When the quake struck late afternoon on Jan. 12, 2010, Freshla nearly died twice. He was on his way to a Vwadèzil rehearsal and was running late after waiting for a delayed money transfer from his brother in the United States. Despite being behind schedule, he recalls letting a car cut ahead of him in traffic. The ground began to shake terribly, and a multistory building collapsed onto the road, crushing the car that had cut in front of his. The rehearsal space he was meant to be in also collapsed, killing two of his musicians. The 7.0 magnitude temblor left some 220,000 dead, according to some estimates, and over 1 million homeless.

“Everyone who had taken that day for granted, who died without doing what they should have before,” Freshla said, “they left without having done it.”

After the dust had settled and most of the bodies buried together in achingly vast mass graves, Freshla was ready to record a new song. He called on G-Dolph, real name Rudolph Archibald, and the two went into the beatmaker’s stuffy recording studio in another corner of Delmas to begin work.

G-Dolph had been at home when the quake hit, making beats on a borrowed HP desktop with a pirated version of Fruity Loops 7 software. It was still early in the carnival season, and he was still green as a producer, but the months before Mardi Gras can be busy for anyone with beats to sell and a recording studio to rent out to other musicians. Where Freshla’s personality is outsize and boisterous, G-Dolph comes across as more shy and dreamy. He smiles slow and big, but sometimes speaks Creole so quickly that his words melt together. He rarely ventures far from his studio, a cement shed built in the courtyard of the house he rents with his siblings, covered with graffiti on the outside and Sharpie tags on the inside.

A couple of broken-down cars are permanently parked inside the front gate, next to a cement wall where someone spray-painted a hesitant “RELAX?” Friends sometimes drop by to slouch into the front seats, doze, or listen to music on their phones. Despite rabòday’s quick success since the quake, the beat-maker says he doesn’t have a functioning set of wheels. An air conditioning unit pokes out from one of the tiny studio’s walls. When the power goes out — which is often — the space swelters, and the door is flung open for relief. On the foam-covered ceiling above his chair, G-Dolph scrawled: “Jesus is my security.”

G-Dolph had tried for years to make it as an R&B singer, and then with a rap crew, but struggled for a break. He grew up surrounded by music in the Artibonite, a lush, rice-growing region in central Haiti. He was raised on the sounds of rara, in particular, and other drum-driven music that is central to the culture and spiritual practice of Haitian Vodou. G-Dolph, he is careful to point out to me, does not practice Vodou himself, but he does carry spirits — and the foundational drum beats — with him.

“This style, the flavor that’s in rabòday, it comes from Vodou,” G-Dolph said. “Directly from the root.”

Like G-Dolph, Freshla grew up steeped in this tradition. His fashion sense and bold style on the basketball court earned him his nickname, and he got it tattooed on his left triceps as a teen, FRESH in wobbly green bubble letters. He says his maternal grandmother was a samba, someone who was called on to lead rara songs, comment, criticize, celebrate, and carry histories; his maternal grandfather, a houngan, a Vodou priest, was known in his community near Miragoâne as a healer. Also like G-Dolph, he points out that he doesn’t practice Vodou, but, unlike a growing number of Haitians, he stops short of disparaging it. Conservative Christian Haitians, following American Evangelicals’ lead, point to Vodou as the reason for Haiti’s ills, while the country’s well-heeled simply look down on it as unfashionable or primitive. But to Freshla, to denounce rabòday because of its ties to Vodou — by most accounts of history, the rebellion that crushed the French colonials kicked off following a secret meeting of slaves in 1791, a historic pact sealed with a Vodou ceremony — is to insult the ancestors’ victory, and what gave Haitians their liberty.

“Even when you play Vodou music, people say, ‘Oh, that man’s a devil,’” G-Dolph told me in his studio. He shrugged, leaning back in a plastic patio chair in front of his computer screen, and said that Haitians would rather give value to music and culture that’s imported rather than their own. “I wanted to give it another kind of touch, to make people accept it.”

With Fruity Loops, he tried to find a way to coax the mystic sounds and street rhythms of his childhood from his head and onto a computer, pulling them tight into explosive BPMs. “January 12, 2010, was the trigger for rabòday,” G-Dolph said; his first recording session with Freshla, a few months later, was the first shot fired.

The summer after the earthquake, they dropped “Boule Jou,” loosely translated as “to spend (or burn) the day.” The song was a post-tragedy call to enjoy your days to their fullest, both an enraged lamentation of life’s injustices — toiling for the money to build a house, only to lose it in a flash to an earthquake—and a don’t-kill-my-vibe bid to party. Over a frantic beat that would become G-Dolph’s signature, Freshla throws up his hands and wails for people to stay out of his way — who knows if we’ll have a tomorrow, just let me enjoy today. Something about the song captured the tension of the months following the earthquake and it became its own kind of catharsis, a summertime anthem for survivors exhausted by tent camps and trauma.

G-Dolph’s samples and rhythms were familiar, but no one had heard them quite like this before. Other producers started trying to pass off G-Dolph’s beats as their own, coasting on his sudden burst of popularity. The shy producer was forced to step up and claim ownership for his songs. When people asked him, what is the name of this infectious music?, he responded: rabòday. G-Dolph called his songs by the same name of a rara style that already existed, and this “borrowing” of the old term would later ruffle some musicians of the older generation. But for a new generation of listeners, the word rolled smoothly off the tongue—rah bo DIE! — and it stuck.

“When I heard ‘Boule Jou,’ I went, ‘Oh, check out the music this dude is making,’” said Thony Mahothière, better known as DJ TonyMix. Each time he dropped the new song into a live set, he watched the dance floor erupt before him. “I was like, fuck, I’m going to get in on this too.”

TonyMix, imposingly tall with a baby face framed by large glasses, was one of the earliest champions of the new sound. He started playing it at parties, mixing it with rap and dancehall, and releasing rabòday remixes, and quickly became associated with the nascent trend. His unofficial title in the streets is “DJ Peyi a,” the country’s or the people’s DJ, a crown that has seen him preside over block parties in the hood, private gigs in the breezy hilltop mansions of Haiti’s young elite, and earned him regular invitations to play internationally. His playlist is broad, but he credits rabòday for boosting his profile — and rabòday has benefited from having TonyMix as its ambassador.

“Every country has its own style, but rabòday is Haitian,” TonyMix said. He calls it a pwodui lokal, locally grown. “When you play it, the crowd goes nuts. ‘Tony, play rabòday; I want to hear rabòday!’”

TonyMix worked his hometown sounds into a set at a massive free concert with Chris Brown and Lil Wayne in the capital in late June, and seemed to make a fan out of Swizz Beatz. Before getting on the plane to Port-au-Prince, New York’s One Man Band Man posted a list with J-Vens, TonyMix and other rabòday and rap krèyol artists to his Instagram. “Sak Pase!” Swizz wrote in the caption. “I’m working on my playlist vibe for Haiti.”

On a Monday evening at the Sky FM radio studios in Petionville, TonyMix was towering over his laptop and mixer while visiting artists and friends lounged around, nodding to his selections and sipping from red Solo cups. He was closing out his last live mix show before leaving for a U.S. mini-tour, but when Freshla walked into the studio, TonyMix looked up. “FRESHLA! KING RABÒDAY!” he boomed into the microphone and reached his free arm out to greet him.

Freshla, TonyMix later told me, usually pushes some kind of message in his songs. “Us, we do things that are funny, to make people laugh, to make people vibe,” he said. “Him, he always has these lyrics, hitting the government with a little something, you know? While you’re criticizing, you’re dancing, too.”

On the song “Dwadèlom,” released at a time when Haiti was in the throes of a political crisis and U.N. peacekeeper sex scandal, Freshla calls out diplomatically immune Pakistani soldiers for raping a Haitian boy, all wrapped up in a singsong chorus that warns against sticking human rights — or allowing a man’s finger, depending on how you translate — up your backside. “Nap Koupe Yo Fache,” a song about miscegenation and racism, was released last year when outrageous legislation against Dominicans of Haitian origin was introduced across the border — the very legislation that has lead to the current crises of statelessness and threats of mass deportation. “Indigenous descendants / We’re oxygen for the black race,” the Vwadèzil chorus sings over a rapid-fire drum line. “You want to deport my mother,” Freshla cuts in, “because I fucked your mother, you’re mad.” Like his samba grandmother, and like generations of razor-tongued rara and carnival singers before him, Freshla has kept the Haitian musical tradition of sharp social criticism alive in rabòday, mixing equal parts politics and humor.

It was a song for the 2012 carnival season by Freshla, another collaboration with his group Vwadèzil and G-Dolph, that helped set the tone for the rabòday takeover that year. “M Pap Ka Ba Ou Metafò’w,” a scathing takedown of the U.N. peacekeeping forces that have occupied Haiti for over a decade, is another a sharp twisting of words. The title can mean, among other things, “I won’t buy into your false talk or hypocrisy,” and “I won’t let you stick it in me.” Over a joyful bounce, Freshla admonishes the foreign soldiers for importing cholera and raping with impunity, and wags his finger at the pants-dropping past of Haitian President Michel Martelly, an ex–music star, for inspiring a poor example. Months after carnival was over, you couldn’t go anywhere in Port-au-Prince without hearing Freshla’s gleeful taunts.

Suddenly, there was an explosion of the sound. Artists who had tried their hand rapping or singing konpa (a syrupy, playful modern Haitian merengue where pairs dance so close, some restaurants confine them to private black-lit rooms), suddenly shifted direction to make rabòday music. G-Dolph was flooded with production requests, and more beatmakers and DJs cashed in on the trend, diversifying the sound’s aesthetic. New hits spawned new slang and dance moves, like side-shuffling “Ti Mamoun” by J-Vens. Rara rhythms had always been around, but the sped-up, raw playfulness of this electronic version began to seep in everywhere. By the following year’s carnival, most of the big anthems sounded a bit more like rabòday.

The importance of carnival in Haiti cannot be overstated. Since Martelly (who was once better known for his career as konpa king Sweet Micky) became president in 2011, his government has presided over seven carnivals — four national Mardi Gras bacchanals plus three summertime incarnations of the Duvalier-era Carnaval des Fleurs — and held exactly zero planned elections. The scope and planning of carnival has changed under the Martelly presidency as well, and increasing numbers of artists release original music in the weeks ahead of Mardi Gras, both to participate in the vibe and in hopes of getting noticed. Last year, over 1,000 songs were produced for the festival.

“It’s flabbergasting that kids with no means are doing that,” said Fabrice Rouzier, a musician and 14-year carnival veteran. “From the guy that will print the CD to the guy that’s performing, to the motorcycle that they have to get to go to rehearsal, they’re putting in an average of $500. So, that’s half a million dollars that these kids with no means are putting into carnival.”

The ultimate goal, of being named one of the dozen or so groups who is given a float to perform on for the three-day festival, is virtually unattainable to all but the most established musical groups. The most an up-and-coming artist can hope for from carnival is to have their song picked up by the radio, get a little bit of attention, and improve their name recognition — and even that is a long shot.

But it worked that way for Freshla. He released his first carnival song with Vwadèzil in 2004 — “M Pa Nan Pale Franse,” or “I’m not down with French doublespeak,” mellow and stripped down compared to the higher voltage of today’s electronic rabòday. The song by these newcomers caught on, and the group has managed to claim a spot on carnival playlists every year since.

If carnival is like the World Cup of Haitian music, then PleziKanaval, created by media personality Carel Pedre, acts as its unofficial FIFA. The website PleziKanaval.com is the most comprehensive source of downloadable and ranked carnival songs, videos, and artist interviews, and last year it expanded to include an awards ceremony to fete the top songs of the season. President Martelly, who took home a lifetime achievement award this year, sat in the front row with his two musician sons, who also both won trophies for their carnival songs.

For the first time, rabòday was acknowledged as a musical category, alongside established genres like rasin or roots, konpa, and rap krèyol. Freshla’s “Ti Pati” beat out the competition to win the trophy for best rabòday song, and the artist took to the stage to accept in bleach-splashed jeans and a tight blue blazer, braids tucked out of sight under a hat. He hoisted the award over his head.

“For lyrics, you have to go to school,” he said. “You can’t pay for it, you can’t buy it.” This was a pointed jab at the musicians from Haiti’s moneyed upper classes who hired other artists to create their hits. Even with a trophy in hand, winner in a category he helped create, Freshla still spoke with the defiance of an underdog who needed to scrap for respect.

The most popular rabòday hit to date was also the one that inspired the most venomous backlash: a 2012 TonyMix remix of Mossanto’s “Fe Wana Mache.” The song is about how to treat a money-grubbing girl who drinks all the juice, with the chorus — “Make Juana walk, make Juana fuck” — spit out over a hard, jagged beat. When the song dropped, it was tough to find a corner of Port-au-Prince where the raw horn blasts of Wana were not pounding from a taxi radio, tinny motorcycle speaker or roadside restaurant sound system. But even as it punctuated the soundtrack of everyday life, it was roiled by public outcry over its deeply misogynist lyrics. Real-B, one of woefully few female voices in rabòday, fired back with her own version about a man, “Fe Wano Mache.” After heated debate, “Wana” was banned from radio and public transport. All the same, Haiti’s only daily newspaper reluctantly named Wana—“a vulgar and antisocial song,” “an indecent musical text”—the biggest hit of 2012. And rabòday, though seen as evermore shameful, was named the sound of the year.

In many ways, and particularly in a country where radio charts are either non-existent or for sale, a song’s ubiquity on the streets and at gatherings is often the most reliable measure of a hit. “They play it in traffic, and school kids catch the vibe,” says the singer Vag Lavi. Lavi’s name means, roughly, “fuck life,” though his real name is Valens Fleurimond. He’s known for his metaphoric word play, blasting out critical social messages, skewering corrupt officials, and encouraging young people to invest in their education. He’s called out fellow artists on their content, sparking a few rabòday rivalries along the way, and drops references to ex-dictator François Duvalier and Haile Selassie over buoyant G-Dolph beats.

Haiti has many rich cultural legacies, but a recording industry and commercial music market don’t count among them. Vag Lavi got a boost from his popular carnival song earlier this year, “Yo Tombe Pou Temperaman Yo,” and went on a mini-tour throughout the country. He encountered traditional rara bands in the countryside that played covers of his song in the streets, bringing rabòday somewhat full-circle.

“Even foreigners wrote to me, ‘you made a great carnival song,” he said. “I was stunned.”

Tickets to his performances hover around $3 USD each, and promoters can be notoriously sticky with payment, if they don’t skip out with the cash altogether. These shows are one of few opportunities artists have to sell albums, mixtapes or other products, though fans rarely wait to purchase songs legally. People with internet access rip tracks from YouTube, share them freely with friends on WhatsApp, and the more enterprising laptop DJs sell playlists for cheap for anyone with a jump drive. It can be incredibly tough for even a popular artist to make money the traditional way.

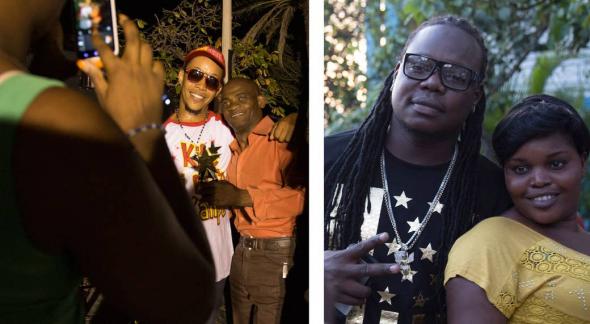

Freshla and DJ TonyMix pose for photos with fans. Marie Arago for BuzzFeed News

Freshla and DJ TonyMix pose for photos with fans. Marie Arago for BuzzFeed News

As a producer with his own recording studio, G-Dolph is in a better position than most, though he says he’s struggling to find the means to release an album with his group, Suspens. These days he charges other artists roughly between $150 and $250 USD to produce a rabòday track. During carnival time, when he’s booked for weeks solid producing songs for dozens of groups, this can pay off. The real cash, though, comes from sponsorships, and for that you need to already be famous in the streets. The laptop he currently uses to make beats, perched above a broken drum machine, was given to him by a sponsor.

Above his tiny studio in Delmas, G-Dolph has tacked a sign: “Anyone who is not working stay outside please!” As an amulet its power is weak, as artists and friends regularly drop by to talk shop, charge their phones, or post up and crack jokes in the shade. One day it’s Sagesse, an evangelical DJ who has a rabòday show on one of the largest Pentecostal radio stations in the country. Another day it’s Master Rock, a defector from rap krèyol, who had his first rabòday hit last year with “Chikangunya,” a song named after a nasty mosquito-borne virus that had the entire region aching with fevers last year.

Once an artist achieves some popularity, they can approach a company for cash or gear, and the sponsor in turn expects heavy promotion of their brand in music videos and song lyrics. The best shot an unknown artist has at catching a sponsor’s attention and catching a hit is by putting out a hot carnival song.

After the PleziKanaval Awards, once the trophies were handed out, tributes were paid to victims of a fatal electrocution accident during the parade, and post-ceremony drinks dried up, Freshla wanted to celebrate his victory. He threw a giant block party in Delmas 5, the neighborhood where he grew up, adjacent to a particularly dicey part of town where gang battles often rage on. When his parents died, he and his siblings were raised here by an adoptive family on a quiet strip of small houses fringed by almond trees. It’s his baz, one of the only places in Port-au-Prince where he can be at ease, and he returns to visit his childhood friends, post up on the roadside with beers, and eat chunks of bread scooped with spicy smoked herring chiktay several times a week.

Two DJs took turns mixing dancehall and rap krèyol with rabòday on an enormous sound system he rented. Girls in neon headbands and men in fitted caps swaggered up the hill as the sun went down, lounging on parked motorcycles or bouncing to the music. The Vwadèzil dancers, dutifully wearing T-shirts branded by their rice sponsor, popped and locked in a tight circle on the street, oblivious to the rest of the crowd. Freshla had barely slept — the awards party went late — but he was on a high. Another sponsor had gifted him cases of beer, and he flew from conversation to conversation, making sure his friends and guests had a drink and something to eat. He occasionally got on the mic and thanked everyone for supporting him. “If there was no Delmas 5, there would be no Vwadèzil,” he said.

By 9 p.m., the road was mostly blocked with parked cars and swaying bodies, and residents were hanging out on their rooftops. A police patrol in a battered pickup crawled through, shotguns hanging out from the open windows; they stopped long enough to give the artist a pound. A DJ dropped “Ti Pati” into his set, and one of the neighbors, a tiny woman in her late sixties, made a face. “I don’t like this one,” she said within earshot of Freshla. She shot me a quick wink, and then sashayed back to where she was preparing a pile of plantains for frying.

A camera crew from the Haitian national broadcaster hung around the edges of the party, waiting to interview Freshla for a cultural TV program. I asked the reporter what he thought of rabòday, and he shrugged, arms crossed. He was really more of a konpa guy.

Freshla in the studio with singer Lunise Morse of RAM. Marie Arago for BuzzFeed News

Freshla in the studio with singer Lunise Morse of RAM. Marie Arago for BuzzFeed News

On a recent afternoon, in the air-conditioned West I recording studio deep in another dusty corner of Delmas, Freshla listened back to cuts of his forthcoming album. He’d just finished recording vocals with Lunise Morse, the singer from roots band RAM, and now he wanted to brainstorm a title for a new song.

This was a song Freshla had recorded in French, an attempt at branching out to a broader audience in the francophone Caribbean — his band name, after all, is Vwadèzil, “voice of the islands,” plural. Haiti is preparing to host Carifesta late next month, a regional carnival for the broader Caribbean, and he wanted to be ready to catch that potential new audience for rabòday. A couple of weeks before the first tourists were expected to arrive for Carifesta, the first round of Haiti’s painfully overdue elections was finally set to take place. August would be busy.

“I can’t call it ‘Bien Vague’ — this is going to be a slogan,” he said, rolling his shoulders. “What? ‘Je Te Donne Vague’?” The expressions, frenchifications of the Creole “bay vag,” referred to brushing someone off, and he wanted the hook to be just cheeky enough that it would catch on the way “Ti Pati” had. It was a challenge; the playfulness of Creole didn’t quite translate to the language of Molière. He stopped dancing to his chorus, paced for a moment, then paused in thought. He looked up, grinning broadly, and clapped his hands. He had it.

“Yeah!” he shouted in English. “That’s a hit!”

Artigo originalmente publicado em Buzzfeed News a 7.7.2015