António Tomás, Deconstructing utopias

photos by Marta Lança

A new writer and a new book have been presented by Agualusa to a pan-African gathering. The book has received critical acclaim as a work by an African writing soberly on “such things”, in “journalistic language, backed by rigorous research.” It is a first in terms of its internal discourse, since it provides us “with a view of an African thinker and fighter from an African perspective.” António Tomás accepted the praises with a typically calm and thoughtful attitude, at this moment of great personal satisfaction after all the struggle and sacrifice needed for a book like this to be published.

A new writer and a new book have been presented by Agualusa to a pan-African gathering. The book has received critical acclaim as a work by an African writing soberly on “such things”, in “journalistic language, backed by rigorous research.” It is a first in terms of its internal discourse, since it provides us “with a view of an African thinker and fighter from an African perspective.” António Tomás accepted the praises with a typically calm and thoughtful attitude, at this moment of great personal satisfaction after all the struggle and sacrifice needed for a book like this to be published.

He was born in Luanda in 1993, Portuguese by nationality. This was the year of war in Israel, of Allende, of oil price hikes, of maximum production levels in coffee and cotton in Angola, of the assassination of Amílcar Cabral and eight months before the Guiné-Bissau unilateral declaration of independence. António was the oldest of the boys among five children. His father was from Malange, though he had a S. Tomé e Príncipe background, and his mother was from Luanda. His childhood was spent in a socialist Angola, a land of bread queues and food coupons but no great social discrepancies.

“My mother was a devout Catholic and didn’t want us to get involved in politics. When other children of my age were going to the 1st of May parades to listen to the president’s speeches, we were on our way to church. Democracy was practised in the church in Angola.” It was here that he had his fist experience as a journalist – with a bulletin put up on a notice board, and he also set up a library.

His love of reading starts with the spoils of colonialism, and he devoured the books left behind by the Portuguese. In the library of the Luanda commissariat he discovered the Americans Hemingway and Faulkner; in the house of a neighbour, abandoned by those who left, he discovered thrillers. But his first serious literary influences were Sartre and existentialism. At 16 he was writing poetry and working on comic strips. He joined the Alliance Française to learn more and go to film cycles. He started on a novel in French, because it was the language where the quality of teaching was the highest. “I realised that I wanted to write and journalism was the closest thing to being an author”. He did the secondary course on journalism while he was working at ANGOP and on Rádio Nacional. He wrote pieces of great passion, but he was also responsible for the script of the legendary programme fronted by the voice of Edite Vasconcelos, “Boa noite Angola!”

He also studied in Portugal. He won a Gulbenkian scholarship and studied social communication in the Universidade Católica. He got to know José Eduardo Agualusa, who invited him to write for the daily paper “O Público”. Here he worked in the cultural section, above all on subjects to do with Africa.

He had never felt really at home in Angola because he never had anyone to share the things he liked, but he found this sense of identity in Portugal. What he found racist and conservative in Portuguese society was “when I left the intellectual milieu to get a taxi or rent a house.” It was a long time before he went back to Angola. During the 90s he watched a country at war from afar and he didn’t even move in Angolan circles because it was “very painful”. This was when the theatre came on the scene. He had already read Ionesco, but it was at a dinner at the home of Ariel de Bigault that he decided to write for this medium with Miguel and Zézé Hurst, because the available roles for black actors were scarce and of limited range. A theatre group with African roots was a pioneering event in Lisbon.

This was when he wrote “Museu do Pau Preto” (The Museum of the Black Stick), a play that took him to Cape Verde. “I enjoyed working as a group, us and the actors, in the first play written, produced, put on and acted solely by black people.” He also wrote a show for “Uma mesa e uma cadeira” (A table and a chair), put on at the Culturgest in Lisbon and a play about Amílcar Cabral in collaboration with the Hursts.

He did a master’s at the Instituto Superior de Ciências do Trabalho e da Empresa (The Higher Institute for the Study of Labour and Enterprises), and he went to the United States to do a doctorate in Anthropology at the University of Columbia, where he spent three years. Before this, however, he won a scholarship through “Criar Lusofonia” (Creating a Culture of the Portuguese Language) and this allowed him to start his research on Amílcar Cabral, a figure that had always attracted him. This brought journeys to Cape Verde, Guiné-Bissau and Paris; there were interviews, letters and more letters and so much documentation in the repository of the Mário Soares Foundation; cross-checking information; building up a profile of this key figure for an understanding of the independence movements in the former Portuguese colonies in Africa; and there were the many sofas kindly made available by friends for him to rest after feverish writing on the extremely full life and the times of this man.

a transformar neste livro.

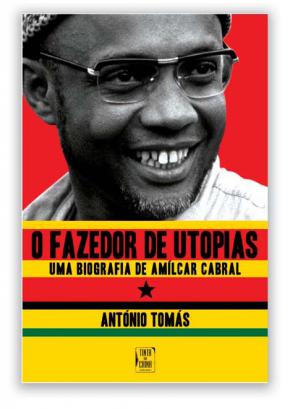

In 2007 the publisher Tinta-da-China gets hold of this fabulous biography, given in by António Tomás – a “stroke of luck” in their words – to turn into the work we have. And so it is here, “O Fazedor de Utopias - Uma Biografia de Amílcar Cabral” (The Maker of Utopias – A Biography of Amílcar Cabral) a work that gives us so much on one of the most important idealists in recent African history. At the end, Tomás says that the most important thing that remains of Cabral is “the humanity, depth of feeling and belief in a better future” of a nationalist figure who, like so many others, had to solve the deep-seated crisis of an identity that was Portuguese and African at the same time. The solution came through the far-reaching self-determination of his people.

in AUSTRAL nº 65, article provided by TAAG - Linhas Aéreas de Angola