An approach to film making in Angola that is consistent, mature and upright, interview with Zézé Gamboa

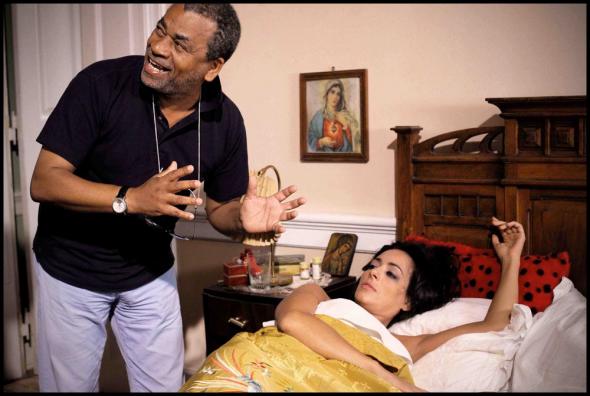

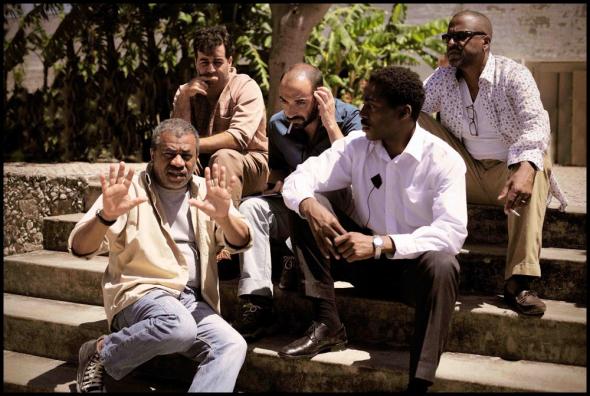

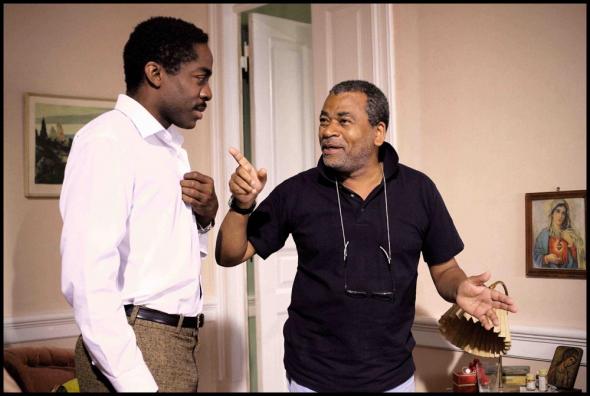

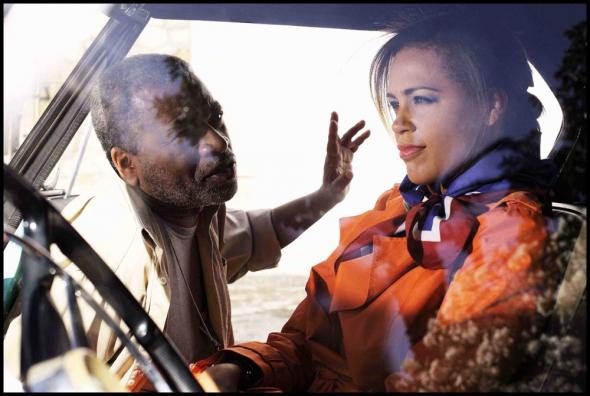

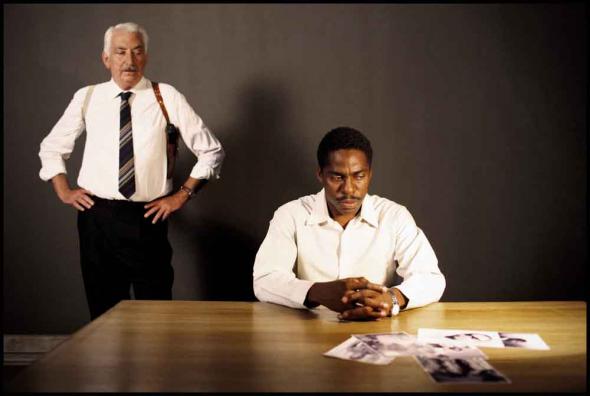

Photo by Nuno Milagre

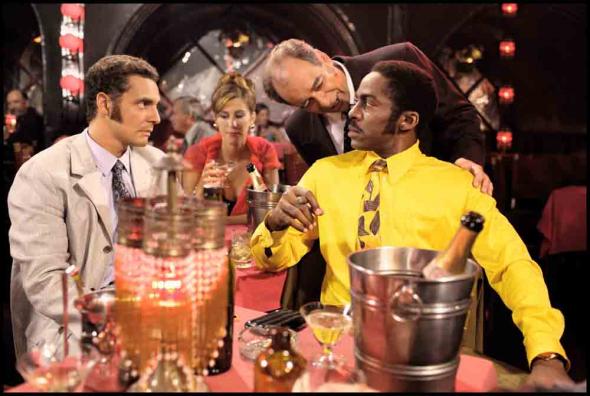

Photo by Nuno Milagre

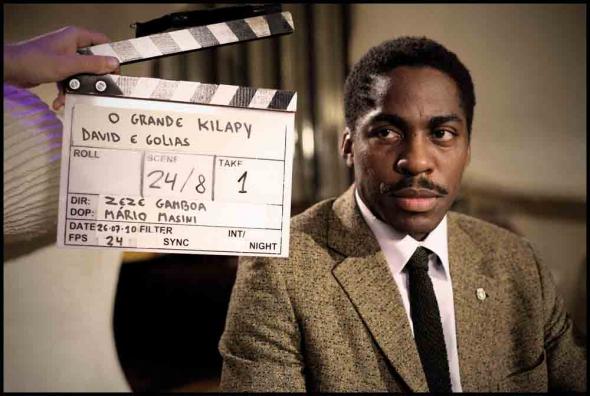

Our interview takes place in Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro, where Zézé Gamboa and a few members of his team are resting for a few days after the intense shoot for his film “Grande Kilapy”, which tells the story of Joãozinho das Garotas, an Angolan during colonial times who engineered a sting with the colony’s finances. There’s just a week in Luanda left for the film to be ready for editing, following the takes in Portugal and Paraíba in Brazil, so this is the right time to weigh up the experience and bring to public attention some aspects of the work done by someone who is considered to be “the most consistent” of Angolan directors.

Zézé Gamboa started in Angolan television in May 1974, as a news producer. He went to Europe in 1980 (nine years in Paris and another seven in Belgium) and then he settled in Lisbon, where he found better conditions for work on his films, both in technical and in financial terms; and it was better for his family too.

“Mopiopio, Sopro de Angola» (1991) was his first documentary – it was a critique of Angolan society, the shortages and the imbalance of the times expressed through music. Other documentaries followed, among them «Desassossego de Pessoa» and «Dessidência». They picked up the thread of a socio-cultural vision, in an attempt to help towards minimising information shortfalls.

But what Zézé Gamboa likes most is to work with fiction. «O Herói» tells the story of a soldier, Vitorio, who returns to Luanda having been mutilated by a landmine. He took a long time over this film but it was worthwhile, since it netted him around 15 awards, among them the 2005 award in the best Festival of Independent Cinema, the Sundance.

The main part is played by the Senegalese actor Oumar Makena Diop, because Zézé is convinced that the quality of films depends very much on the performance of the actors.

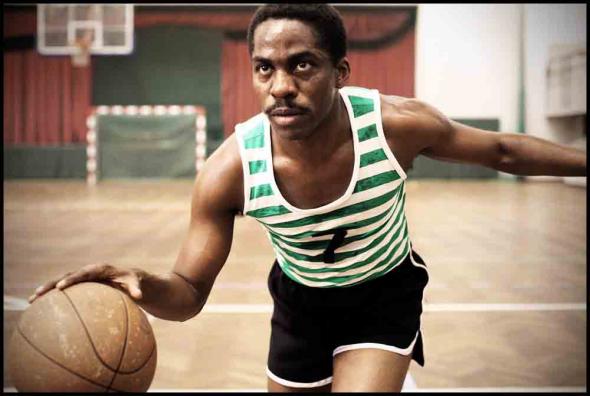

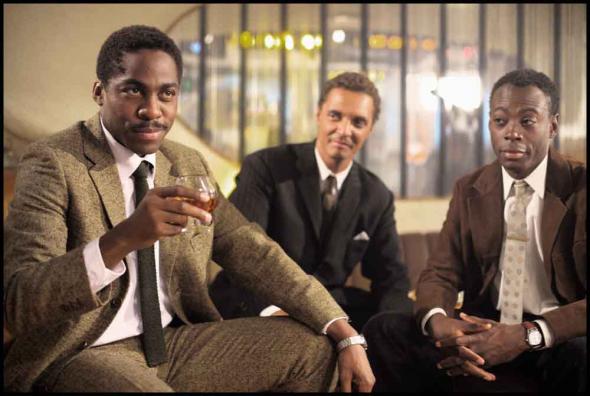

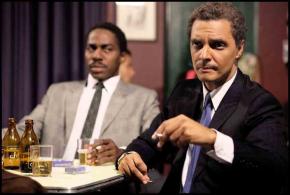

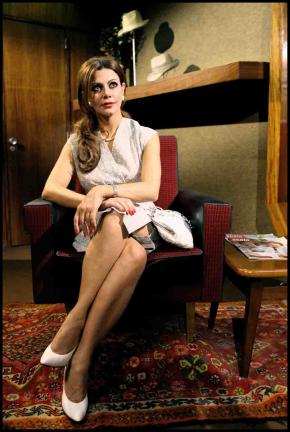

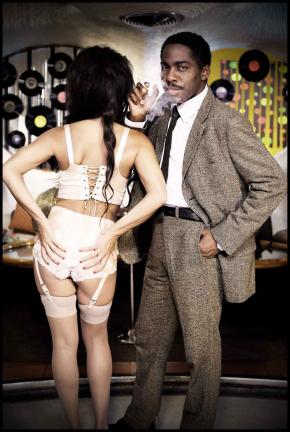

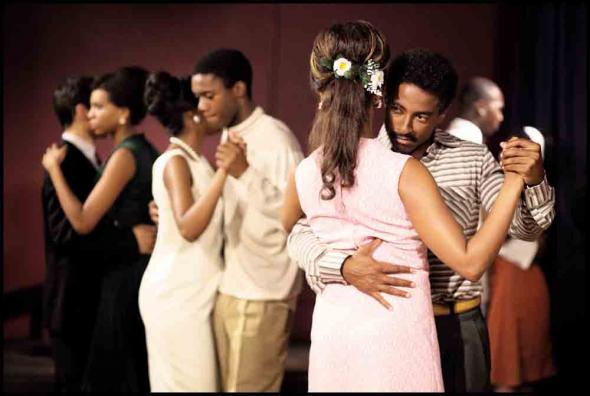

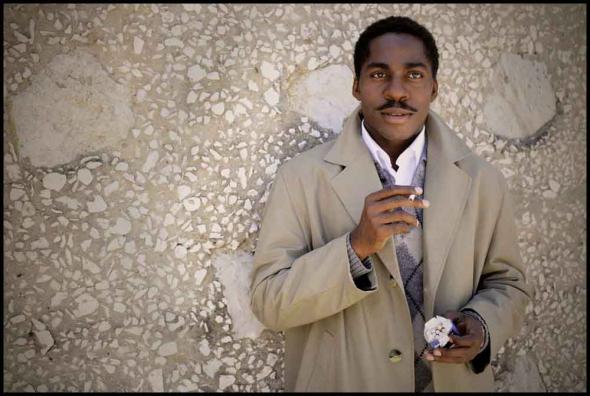

We will soon be seeing “O Grande Kilapy”, a working of the Angolan notion of what makes a ‘sting’, ‘scam’, ‘trick’, ‘borrowing without paying back’. We will see a real character who became known as Joãozinho das Garotas, with thirty years of happiness, bustle and style under his belt (conjuring up the music of James Bond’s Goldfinger). The film portrays the sixties and seventies, both in their darker side and their pleasure. This was the period when Zézé Gamboa was a student in Lisbon, involved in political agitation, watched over by the secret police (the PIDE), a period of love and passionate affairs, the financial sting and jail.

The cinema-goer will recognise many aspects of Luanda under the colonial regime and Lisbon under the heel of a fascist dictatorship, which lasted until 25 April 1975.

António Pitanga, Maria Seiça, Zézé Gamboa e Lázaro Ramos

António Pitanga, Maria Seiça, Zézé Gamboa e Lázaro Ramos

The actors and indeed the whole crew speak of Zézé Gamboa with great respect, because making films is not just a question of suffering. There is a big part forf pleasure in this profession. This is a full-length feature film and a period piece into the bargain, a fact that is to be hailed as loudly as possible, since film production in Angola is still a precarious undertaking, indeed almost non-existent. Zézé Gamboa continues to keep faith with the cinema!

Why did you choose to make a period piece, a film set in colonial times?

This kind of thing just happens. I may not have thought about it early on, but I’ve noticed what is happening in my career: first I make a contemporary film, then I go back in time. It happened with Mopiopio, which came out in 1990, followed by Dissidência set farther back in time. The film Herói tells of the struggles of the civil war and now this one, Kilapy, goes back to colonial times. I was interested in telling a story from a none too distant past, a tale which is part of Angola’s history. Whatever the feelings one may have of colonisation, it’s nonetheless part of the country’s history.

Does the film help in reaching a better understanding of the complexities of that point in time?

The history of the colonial period was never straightforward, and to understand the attitude of society and the way of being of the time, I think the film is important, not only for the Angolans, but also for the Portuguese. Of course there is a vision which is mine, because when you make a film, you draw the spectator into what you are portraying. But there is something of what society was like and the codes and customs in the colonial era of the 60s and 70s.

What attracted you to the figure of Joãozinho das Garotas, the good villain type?

The film starts with a true story but then a lot of fiction is mixed in. The life of Joãozinho by itself could make another film, but it wasn’t the film I was making. I wanted to put across the idea of various concepts of nationalism that were there in colonial times, rowing against colonial codes, which is what Joãozinho did. If there is one interesting thing about this, it is the subversion of the history of colonisation, one of the victims striking a blow against the aggressor. The story is only possible in Angola. I worked up to eight versions with Patraquim and when he heard the cassettes with the story of Joãozinho he said: “this couldn’t have happened in Mozambique.” We are talking about the same colonial power with different ways of being in its colonies. In Angola, colonisation was really perverse: there were colonials who lived in the slums and Angolans who lived where the streets were of asphalt. In the pictures of the times, we see white folk selling in the market.

Is there a lot in the film based on the biography of Joãozinho?

Joãozinho comes from a lower middle class family, from a traditional Luanda family, the Farias. He stayed in Luanda until he was 17 and then went to mainland Portugal to study. It’s true that he struck a blow against the colony’s finances. It’s true that in the Tamar (the nightclub) he was known as Goldfinger, because the orchestra there played the theme song from the film when he came in. He really did have some top of the range and swanky cars. There was, for example, his friend Pedro Gomes, who came from a well-off family (his father was an official customs agent and made a lot of money) and he did his military service and then became one of the first blacks to have a top position in Shell. I gave more emphasis to the main character, and if the film had been about Pedro it would have been different. I interchanged features of the personalities, making Pedro more serious and Joãozinho more of a joker.

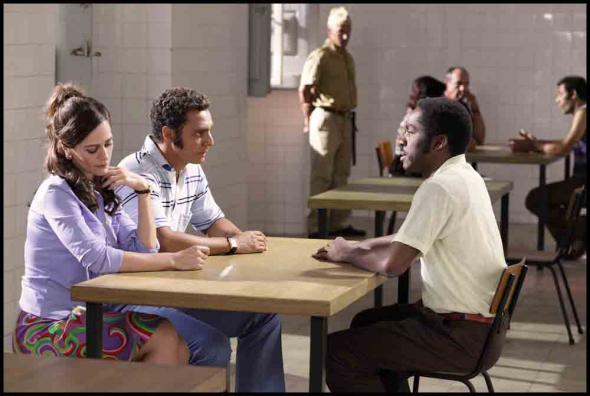

Joãozinho went through the world of anti-colonial resistance, in the Students’ Hall of the Empire, and he was imprisoned by the secret police (the PIDE), he knew militant communists, he joined the students’ struggle, but he never got really involved.

He had friends there, but he wasn’t directly involved, to judge by what he told me, but there are some contradictions. What interests me is that the story took place in the golden period of the freedom and nationalist movements. He helps the character Rui to flee, through the Portuguese communist party, and then he supports the MPLA. And Ito any spectator who was less aware or less involved in politics, I wanted to show that it was important at that time to support the liberation movements. There are scenes of partying in the Students’ Hall and as this was a closed world, the atmosphere comes through, helped by the wardrobe, the hairstyles…

“He was generous to his friends and open-handed with women”. What kind of weaknesses and complexities does this hero (or anti-hero maybe) have?

This business of the ‘chicks’ (the girls) is another story. He had a very friendly side, and was there for his friends. He was a friend of your friend, and gave of himself willingly. His friendships were long lasting, he was a man of character, upright, something that I admire in people. It’s very important. In today’s Angola, there is less generosity than there was in those days. It’s very easy to tread on those who are weaker and kow-tow to the powerful.

What risks are there in making a film of the recent past?

The main risk is that those who were close to João or were part of his group, could look for what they lived through and what they wanted from the film. But what interests me is the way I am going to tell it and not the veracity of this or that specific point. Different readings and ways of arguing are part of the process. When we make a film, we are baring our souls; we have to know what makes our public tick.

And the problems, in technical or logistical terms?

There is never enough backing. We are never happy with the budget we must work with. But it can be done, though the money available could be more and better managed.

Was it possible to shoot the film in Luanda?

Totally impossible, because it is set in the colonial middle class and you couldn’t bring in white actors to film in Angola. And those that are there couldn’t give up what they were doing to be on a film set. And there was the problem of the cars. The city was also very different. Today the houses are bunkers, where before, people could look inside. People can remember, and they recall what it was like. Then there is the overall chaos, the atmosphere, the construction work in a city which was so unlike what you’d expect. And above all it would have been very expensive. You could do a film if you could take your time and the Luanda setting was today.

Lisbon and Luanda are two stages for the film’s narrative. How were you able to get around that?

We filmed in Portugal, Lisbon, and in Paraíba, in João Pessoa. There were problems, because the producers changed the number of weeks we had to shoot in Brazil and the film we had conceived had to change completely as a function of that fact. It created conflict in the production, financial losses, it wrecked the planning and there were problems with actors that you wanted in one place or the other, and so on. Cinema is all about telling the truth while lying, but to be good, you have to know how this works. Putting together a film set in a week leaves you weak and stressed out.

So how did you keep your cool and your sense of humour?

I had to swallow hard more than once. And not just for small things. Enormous ones too. What’s important is to make sure the film gets done, and done well.

How do you manage to keep your cool when filming – something that everyone refers to as an example of a director without an overblown ego, who never raises his voice and always shows such respect for his team? Can you learn something like this or is it part of your character?

Part of it is a question of maturity, and I’ve acquired that. I always kept in mind that I wanted to complete the film, and if I had got desperate, it might have jeopardized the whole enterprise.

What were the most positive aspects of the filming process?

I came through the filming with a great feeling of solidarity with my team. They went for the project heart and soul, they gave of their best and this stopped worse things from happening. There is a spirit in people that can overcome everything.

Much of this is because they believed in what you were doing.

Yes. If I had come over as very weak, that energy would have been a great burden. So my own angst had to be managed as tightly as possible, without coming to the surface at all. After all, all the trials and tribulations are gone and forgotten, and what remains is the film itself.

The cast is made up of Angolans, Portuguese, and Brazilians. Why did you choose Lázaro Ramos as one of the main characters and not an Angolan actor?

I could see nobody else in the whole Portuguese-speaking film scene. Lázaro is an excellent actor and he could shoulder the burden that it took. Like in O Herói, these are films about people, and if the main character is not a good actor, neither is the film. I knew it had to be an actor who was very consistent and rock-solid. This is what would make the film a success. He has everything that a great actor should have. He’s generous, attentive, he brings solutions to what might otherwise be less readily understood, he and the film are as one. That’s the difference between a great actor and one that is so-so. And he is humble enough to want to understand it all. In the language, for instance: if the feel was different in Brazilian Portuguese he would try to understand why and how it was different.

One of the things you notice abut this film is the pot pourri – the cultural mix in the team. What did you learn most in all the interchange involved?

One of the things you notice abut this film is the pot pourri – the cultural mix in the team. What did you learn most in all the interchange involved?

The only thing it all did was to enrich the mix. This is one path for the co-productions of the CPLP (productions involving the capitals of Portuguese-speaking countries around the world). The cultural mix is always important, we al work differently, and a dish served up with this mix is more of a pleasure that a dish which is only one nationality, where people are much more tyrannical, more rigid, and masochistic at the same time, since they think that they have to suffer a lot.

And you all enjoyed yourselves, or was it more stress than anything else?

We suffered but we enjoyed ourselves. It has to be good if you can get pleasure from what you do. I like being a director among friends, as I am for instance with the Angolan sound technician Gita Cerveira.

How do co-productions work out as the final product for the marketplace?

In terms of language, there have to be two versions – one Portuguese-Angolan and the other Brazilian. Quite clearly the latter will be a greater success in Brazil than the other version elsewhere. There’s nothing you can do about it: there are 15 million Angolans and 10 million Portuguese, and in Brazil you’ve got 200 million before you even start. Co-productions are in principle a win-win for Brazil.

It’s strange, because we hardly get anything from Brazil here in Angola…

Only in literature, but that’s really an elitist thing. In the way of films, there’s nothing.

What is there still left to shoot?

We’re going to shoot scenes along the coast road and in the new cafés that front the road. This will provide a counterpoint, contrasting the Luanda of colonial times with the Luanda of today. That’s the part where Artur, the film’s narrator, tells the story of Joãozinho to younger people, those who were born knowing about the 25 April revolution. He is on-stage but he’s also there in the background: he links situations in the film’s narrative. This is interesting because it gives colour to the film, it adds to the mix. The narrator tells the story from today’s angle in Angola, though the films starts in 1973 and then we go back to 1965.

So what happens to Joãozinho?

After the sting he put together, he was arrested and charged with theft. There are various versions about how he was caught. The film follows one version, that there was a colleague who realizes he’s embezzling and snitches. João is released from jail along with political prisoners after 25 April 1975 (the date of regime change in Portugal).

in AUSTRAL nº 82, article provided by TAAG - Linhas Aéreas de Angola

Photos by Rui Carlos Mateus