“See a Black Man on Fire”, Complô by João Miller Guerra

Between rage against the machine and the tenderness of a track for a spouse, João Miller Guerra’s Complô portrays a country still afraid of the fire it lit itself

Lisbon looks uncommonly gray as a body was laid to rest in the heat of July. A vigil for Bruno Candé, a young Black actor gunned down by an old white man shouting racial slurs on a random city street. The camera doesn’t flinch. In Complô –– Portuguese for a plot, in the sense of a fix or a systemic conspiracy –– this is the opening bar, the opening chord: a wound, a rallying cry, and a roadmap for a movement.

A voice, deep and sharp as a razor, wraps itself around the grief like a tourniquet. Ghoya, alias of Bruno Furtado, stands before the crowd, fired up, eloquent, enlightening: “Isto afecta a vida de todos vocês aqui.” The pain is his, yes, but the target is collective. His story — he’s an ex-con, a father, a husband, a rapper, the somehow undocumented Portuguese-born son of Capeverdean and Santomean immigrants — is not an isolated administrative tragedy. It’s a case study in (deliberate) systemic collapse. In post-colonial Europe, Black life remains negotiable. Legal papers are optional, lost in the meanderings of changing laws and people who can’t do anything about your case. Dignity is conditional. And rhythm is resistance and indignation.

But indignation that has not lost its soul. There’s this tender, telling moment at the sound studio in Lisbon’s South Bank: during lunch break, João Miller Guerra (often on screen, a disarmingly warm feature of his allyship in this intimate documentary) funnily confides that his daughter’s teenage boyfriend now pretends to understand Kriolu because “it’s cool.” Because it’s got flow. Ghoya bursts out laughing. Not mocking, mind you, but recognizing the sheer absurdity, the irony, the full-circle ridiculousness of it all. The very same language that’s policed and profiled on the street, banished in jobs, and ignored by institutions past and present, is suddenly trendy in hip white spaces. Kriolu as consumable fashion. Kriolu as a flavour. Kriolu as cultural cachet for white kids (and, if we’re honest, filmmakers). But not Kriolu as a right, as culture, as rootedness. The joy in Ghoya’s genuine laughter is mixed with the disbelief of someone who knows exactly what it means to be a speaker of Kriolu in a country that still refuses to hear him. He codeswitches constantly, like any TCK (third culture kid) I’ve ever met, between formal, Portuguese, deep-cut Kriolu fundu, Lisbon slang, and American linguistic mannerisms.

“They steal, they traffic / and then they want to judge me?”

Weaving rage into rhythm, Complô is a film about a man who often appears exhausted by the system but refuses to be broken. A documentary that finds its cadence somewhere between the furious bars of Rap Kriolu and the gaps of a Kafkaesque immigration system. Directed by João Miller Guerra, and co-written with Ghoya himself (along with many others in the credits), the film follows the rapper’s post-prison life in the margins of Lisbon –– a space the system wants him in –– and through his fight to be recognized by the only country he’s ever known. The same country that, for decades, has tried to write him off administratively. Literally write him off.

Much like the man at its core, Complô carries contradictions with pride: it’s intimate yet explosive, raw yet restrained, heavy with pain yet light on its feet. The cinematography is modest, sparse, and sometimes plain. But its emotional intelligence is astonishing. Vasco Viana’s camera at Miller Guerra’s direction — close enough to breathe on the subject, then pulling back just when needed — creates a rare sense of intimacy conceded by Ghoya himself. This is not an aesthetic feat, but an ethical one. Letting the subject lead, letting his silence speak, letting his intensity and fury sing.

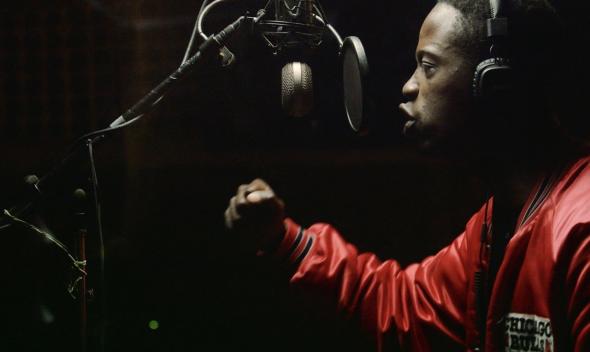

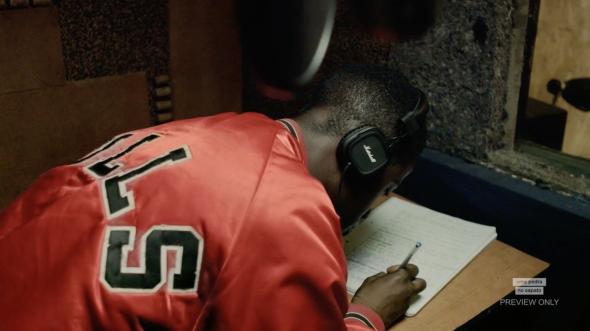

Take, for instance, the seven-minute sequence beginning at the 15-minute mark. Ghoya is in a makeshift studio — plywood insulation, faux Moroccan rug on the wall ––, a beat looping low. He paces, bouncing, rhyming in bursts. Words pour out of his mouth and onto the page in rapid-fire Kriolu, heavy with code-switches: Lisbon slang bleeds into the verses and the interstitial exchanges, flipping between “djam fadja” e “ya, um coche”. In the recording booth, red Chicago Bulls jacket on, he locks in:

“Nobody has heard me say to date / that I am the solution

But for sure, bro / I am part of the resolution

My cause is just / nothing will extinguish my fire (…)

In the darkness I’ll be light / till I die I’ll keep learning

Love me, hate me / fuck this m*therf*cking plot.

Beyond lyricism, this is political testimony. Amílcar Cabral equipped with a Roland 808.

“On the other side of the law”

Midway through the film, in one of its most quietly shattering scenes, Miller Guerra drives Ghoya across the 25 de Abril Bridge — Lisbon’s symbolic artery, named after a revolution, no less — into a fog of bureaucratic cruelty. A polite call. A missing residence card. A life held hostage by invisible paperwork. Wondering how to visit his pregnant partner in the UK, Ghoya asks a nice enough civil servant (herself with a foreign accent, if I may add) if he’ll be allowed back into Portugal. SEF, the now-defunct border service –– replaced after a murder scandal by AIMA, a new low in the purgatory of useless institutions serving the purpose of spearheading multiple governments’ shambolic and systemically ethno-xenophobic migration policies –– hasn’t issued him proper documentation, although he’s lived here all his life.

The answer is chilling: “If you’re stopped by the police here, you’ll be going to Cabo Verde.” The chill of administrative cruelty. A candid voice on the other end of the line, exercising life-altering power with bureaucratic detachment: “It’s amazing how naturally you can say something like that,” Ghoya replies incredibly politely, given the circumstances, before hanging up.

A man in the passenger seat of a car, driving slowly through a neighbourhood he calls home, realizing that his freedom is provisional. His citizenship conditional. The line between leading a normal life and living in state-sanctioned exile? Paper-thin.

Studio. Street. State. Repeat.

Complô is not content with neat narrative arcs. This is not a redemption tale. There is no triumphant comeback concert, no Disneyfied reintegration. Instead, the film braids studio sessions, bureaucratic conversations, the self-doubt of fatherhood, and raucous ciphers into a loose, contrapuntal structure. We see Ghoya in vulnerable moments, struggling with job interviews, money, and insidious bureaucracy. We see him defiant, spitting fire in Kriolu about cops, injustice, systemic cruelty. We see him soft, sweet-talking his partner in earnest rhymes that are love and apology: “Badjuda, don’t doubt for a second / I’ve long given you my heart.”

This contrast makes the film sing. But, while Complô lives in between the classic genealogy of Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine and the great music/artist profile docs, what strikes me are the feelings brought up in Ciara Lacy’s Out of State, where Polynesian inmates in an Arizona state prison reconnect with identity through traditional chants, and where the roughness of these huge, tattooed men is replaced by a softness we also see in Ghoya. Or in The Work, where men incarcerated in Folsom Prison perform emotional exorcisms in group therapy, in what constitutes a tear-jerker of a cinematic piece on masculinity. But Complô is different, of course. It doesn’t take us inside the prison walls. Instead, Miller Guerra and Ghoya managed to showcase that prison is a system that lingers after release. In job rejections. In the documental limbo. In suspicion. In silence.

“They won’t lock me up again.”

After an intimate extended opener, at the exact halfway point of the film, we’re back on stage. Beat pounding. Ghoya is a storm of righteous fury:

“F*ck justice

The youth is lost in prison / Is that justice? (…)

They’re not good people

Instead of a heart / they have a boulder

I am the nightmare.”

Beyond catharsis, this is an indictment. Of a social system. Of SEF. Of systemic racism. Of a justice system that rehabilitates nobody and punishes everyone, inside and outside. Ghoya is not asking for sympathy here. He’s spitting truth. And if his verses are furious, it’s because they must. As one lyric declares: “How many sons will the state / take away from their mothers?”

The antagonist isn’t a person. It’s a system. Faceless, paper-clipped, trained to look away. Miller Guerra knows this. In one standout scene, Ghoya speaks to an institutional figure — likely a caseworker or parole officer. We hear the conversation, but the camera never shows their face. It doesn’t have to. Because the antagonist is the structure, not its agent. And that’s the brilliance of Guerra’s direction: he films not confrontation, but cruel, sisyphic repetition.

“See a Black man on fire / these dogs won’t stop me”

In an interview about the film, João Miller Guerra muses that “we have to accept that there is racism in Portugal.” And while he may mean well, I find myself collapsing under the weight of that phrase. Accept? As if this isn’t abundantly clear. As if racism were still up for debate, a hypothesis awaiting confirmation from think tanks, scholars, commissions, or middle-class dinner tables. That discussion, in Portugal, is exhausting. It’s part of what we see etched in Ghoya’s face in the quietest scenes: the fatigue of having to prove your experience over and over and over again, while the system reshuffles the paperwork of your life. Meanwhile, scholars and pundits out there bend themselves backward to measure degrees of racism in comparison to “the rest of Europe”, even as the far-right grows unfettered. They lost the plot. And the credibility. What they haven’t lost is their hypocritical white fragility.

That same intense white fragility that leads a random white man (because, of course he was) in the audience at the film’s closing concert at DocLisboa. One would guess him an ally, given his presence at the event, but he suddenly heckles Ghoya at the most inappropriate moment, exactly at a brief interlude from furious Kriolu to a few statements in Portuguese on the ongoing impact of racism and no longer wanting to prioritize white comfort over the righteousness of his message. Ghoya impatiently addresses the man whose face I didn’t see, calls him out, engages with his unwanted forays, perhaps beyond the grace he deserved. Then eventually calls it off with a line we’ve heard him rap: “Mano: this is not about you! This is not about me! This transcends both of us.”

In that crowd, hands raised high, I recognize a man from a scene in the movie. In the break, right after this heckler has been handled, he tells me of how his white supervisor recently reprimanded him for speaking Kriolu to assist a customer: “We don’t speak that language here”. Never mind that downtown Lisbon today greets you in English, or that he’d be expected to accommodate a blonde Californian “digital nomad” living in Portugal for two years but unable and unwilling to utter three words in Portuguese. The target wasn’t the language, but what it represented: his Blackness, his otherness, his ungovernability. No different than when the Estado Novo shut down Kriolu and batuku drums. The man I met no longer works there. Something broke inside him that day, he shared, and I could sense it too. But here he was, arms up, wearing his Amílcar Cabral toque, part of the movement. They tried to erase him with a sentence. Instead, he became part of the chorus. As Ghoya spits: “They have yet to understand / That they’re not just fighting me / I bring a whole community in my wake.”

“They’ve taken down the ghetto / but we’re still standing.”

I widen the lens here to reflect on something in the news on the day of that closing party at DocLisboa (where Complô took home an Honorable Mention), involving another fearless MC. That day, CHEGA deputy Filipe Melo sneered across the aisle at Socialist deputy Eva Cruzeiro, aka Eva RapDiva, yelling, “go back to your country!” With unflinching resolve, she pressed the red button and fired right back: “I am in my country.” Then — eyes locked, voice firm, unshakable –– “and you, sir, will come to miss all the times you didn’t hear my voice in this Parliament.” This is no rebuttal. It’s reclamation. Portugal, you’ve been told.

The final act of this film also pulls no punches, but changes it up. Back in the studio — that ramshackle haven tucked between housing blocks in the South Bank — we hear this shift. Rage gives way to tenderness, perhaps because tenderness is more powerful. Ghoya records a track for his partner. His voice slows, softens. “Baby, we deserved a movie,” he says. And in a way, they got one.

Complô is a call to stay standing. To speak the unspeakable. To love loudly. To resist quietly, if that’s all you can do. As the credits roll, we see him quietly vibing to the beat, head bobbing knowingly. Eyes glistening. His words are no longer barbed wire, but balm. The system hasn’t changed. His papers haven’t come. But he’s still here. Still rhyming. Still refusing to disappear. Still living. Still loving. Intensely.

Main Credits:

Cast: “Ghoya” Bruno Furtado, Editox, Laysla G., João Miller Guerra, Vasco Viana, Daniela Soares, Rafael Cardoso

Director: João Miller Guerra

By: João Miller Guerra, Ghoya, Vasco Viana, Rafael Cardoso, Pedro Cabeleira, Daniela Soares, Filipa Reis

Director of Photography: Vasco Viana

Sound: Rafael Cardoso

Production Coordination: Daniela Soares

Editor: Pedro Cabeleira

Colourist: Rita Lamas

Assembly/Sound Mixer: Carlos Abreu

Producer: Filipa Reis

Production: Uma Pedra no Sapato

World Première: FIDMarseille: Marseille International Film Festival 2025

Portuguese Première : Doclisboa 2025

Photography Courtesy “Uma Pedra no Sapato”.