All over Africa there is a certain revival of an industry of culture and memory, or perhaps even the cult of memory. And that might be good news. These memories, obviously unforgettable, are also - paradoxically - very much absent from the day-to-day realities in many African capitals, particularly in countries like Liberia, where the management of a precarious post-conflict balance and of social, civic, and personal trauma is simultaneously the management of the absence of “before”. Younger generations, usually too young to remember, grew up in a “today” in which history ceased to exist, since war deletes past and present to allow a semblance of future to flourish. It often becomes known and told by contemporary narratives, northern narratives… Middle generations, raised in the midst of the civil war, forget as a comforting answer to trauma, for want of inner peace, of for the simple need to to move on from fresh images of violence and, by association, everything that came before it.

While often taken for granted, both photographic and cinematic memories are nonetheless either totally absent or gravely remiss in many countries recovering from civil wars. Archives have often been bombed, looted and burnt, or simply flown out by formal colonial powers when it’s time to go… to preserve its own memories of the place. Veronica Fynn, a Canadian researcher of liberian descent, underlines that the absence of these memories hurts in the deepest confines of the soul. It hurts not to remember the face ofone neighbour of ten years, or the number of spots in one’s childhood dog, or to remember those red shoes that will not materialize in any photograph, because they’ve all been burnt. Fynn, today a Vancouver resident, does not hesitate in pointing the main fallacy of the project by the two British Columbia photographers/filmmakers Jeff and Andrew Topham. “As kids, because of dad’s photos, Liberia became the place we were from”, say the Topham brothers. In

Libéria 77, co-produded by Canadian public indy powerhouses

Knowledge Network and

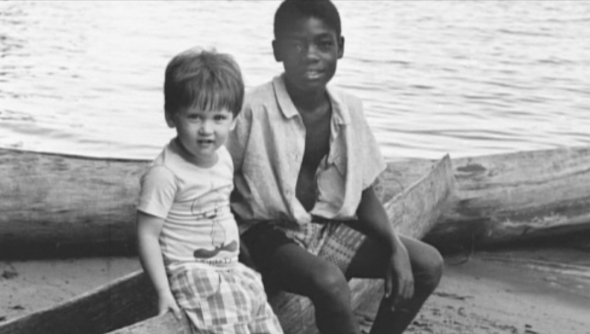

TVO, and presently doing the rounds on alternative circuits, the two brothers emphasize their own experiences as kids growing up in Liberia up until just before the civil war. They go back to Liberia to return memories found in their father’s box of photos. Simple, everyday pictures.

This process proves cathartic both for the artists and for some of the characters they come across (including the son of their former ‘houseboy’). The problem pointed out by Fynn, however, is apparent: theseare Liberian memories being returned to Liberians, but not dictated by Liberians themselves. Perhaps they were never LIberian memories after all, but rather Other’s memories of Liberia. In one of the scenes, an interviewee is moved to see photographs of his family he never even knew existed. The sole photograph he owned after the war was that passport-sized face on an identity card. The project is self-reflexive enough to understand this limitation and this contradiction, accepting it as a lesser evil and a necessary step toward remaking normalcy and reminding the viewer that this Africa in which civil war, trauma and social chaos are so pervasive is not all that Africa is. Africa is also a pair or red shoes on the day of a Christening, a spotteddress on that family luncheon, or a summer ‘78 trip on the pick up Dodge. But, reflexive or not, the Topham’s film and photographic memory project does open up the floor to debate over the ownership of memory.

by Pedro José-Marcellino aka P.J. Marcellino

Afroscreen | 15 May 2012 | memories, photographic heritage