A chicken on a donkey wanting to go to the beach

On wanderings, invisible borders, and a city of Lisbon shimmering in the distance

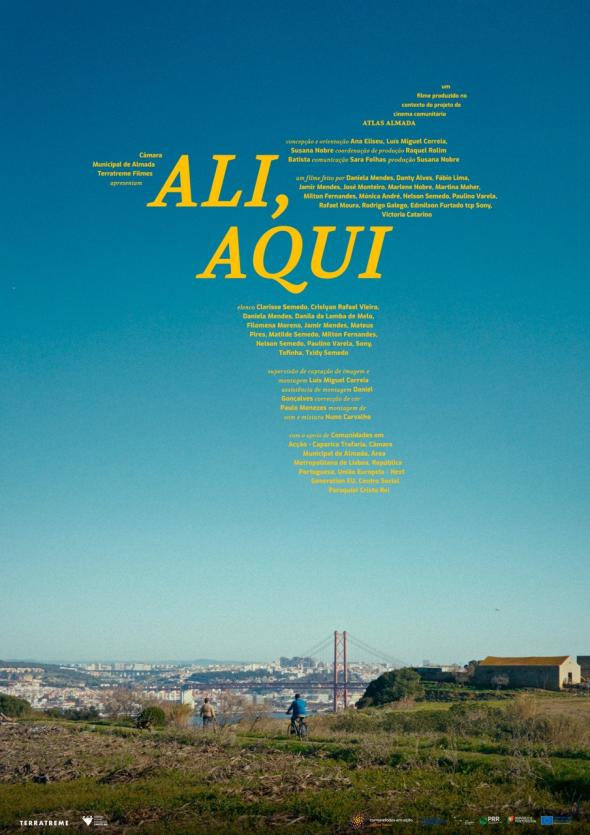

Ali, Aqui opens with a memorable scene: a thick, tangible wind, almost palpable on this side of the screen, sweeps through the abandoned corridors of a ruined asylum in Lisbon’s South Bank, overlooking the city, the April 25th Bridge, the orange cacilheiro ferries tugging across the river. The camera advances slowly, as if feeling its way through memory, along gutted walls, tattered curtains fluttering in the draft, collapsed staircases, narrow, angular passageways, wrought-iron window grates facing the Tagus, objects from suspended lives. A voice over the wind — grave, serene, nostalgic — summons a different time: “I remember the sound of the birds… the gardens… elders’ accents calling for us at dusk.”

The shot of this ruin eventually dissolves into an emotional geography. The asylum, once informally occupied by Capeverdean families, long predates their relocation to Monte da Caparica, a moment the narrator recalls as both tragic and salvific.

When the camera finally pulls back and the frame widens to reveal the Tagus on the horizon, with Lisbon beyond it, the shimmering, whitewashed cityscape reinforces an allegory: some neighbourhoods live with Lisbon in plain sight, yet never quite reachable.

In the relocation neighbourhood of today — glimpsed at first as a reprise of that travelling opening sequence, moving through worn streets and intersecting with its daily rhythms and intimacies — a conversation later unfolds between two companions, distilling, in a few lines, all about belonging and unmooring, about migration and diaspora. They talk about origins: one born in Santiago, Cabo Verde; the other born and raised here in the Monte, never having left it. He had planned to travel to Cape Verde for his great-grandmother’s hundredth birthday — “except she decided to leave at 99.” A sliver of Creole humour that the friend quickly mirrors. So you’ve never been to the land of your people, he beckons, then goes for the dig: “You’re like a chicken perched on a donkey trying to get to the beach.”

The sting lands. It’s likely not the joke itself, but the exhaustion of having one’s emotional home interrogated once again — an exhaustion that echoes the also constant questioning of his belonging in Portugal. A moment of subtlety, a quiet test of roots, reminding us that even among “equals,” borders reproduce themselves. Sensing he struck a nerve, the jokester gives his friend a conciliatory pat on the shoulder: “You may have never been to Cape Verde, but Cape Verde is inside you.”

Portraits of the Invisible City

The film’s fertile terrain lies in the interstitial spaces between li (here) and lá (there), in the liminal lives and livelihoods, between memory and present, between those who arrived and those born here but carrying another land with them, between a country that calls itself modern and the persistence of underserved informal settlements that persist — despite decades of promises of dignified and universal rehousing — as mirages on the periphery. Rather than an ethnographic outsider’s look, Ali, Aqui proposes a wandering story told from within, a community fiction rather than a docu-drama, based on the rhythms, languages, emotions, textures, pains, and humours of those who inhabit the community.

An auteur cinema signed by an entire community, portraying itself from the inside out.

What makes Ali, Aqui particularly distinct is its refusal to turn the neighbourhood into a simple narrative device. The neighbourhood is the narrative, not a backdrop, nor a diagnosis. It moves through intertwined daily lives with a naturalness that could only come from genuine intimacy and knowledge.

Parallels could be drawn with João Miller Guerra and Filipa Reis’ Li Ké Terra (2010), which captured the lives of young Capeverdeans in a liminal space with rare attentiveness. There is perhaps a kinship, too, with The Last Harvest (2025) Nuno Boaventura Miranda’s latest film: shot in the Capeverdean hilltop allotment gardens in the outskirts of an undisclosed suburb of Lisbon, its mirage of the city down in the valley finds evident echoes in Ali, Aqui –– evidence of a continuum of conceptual existence. Cabo Verde at Portugal’s edges. But the closest genealogy may be found in Basil da Cunha’s long-run work in/with the Capeverdean community in Reboleira, his own neigbourhood: After the Night (2013), The End of the World (2019), and Manga d’Terra (2023), a sort-of trilogy filmed from within, with non-professional actors who also happen to be his neighbours, friends, and family, in a true love letter to a community.

Ali, Aqui inherits these lineages, but does something new: this is fully-fledged community fiction. Not only filmed with the community, but by it. The democratic authorship — with its long list of names in the credits — goes beyond symbolism, becoming a production model and a production ethos. On the antipodes of the artistic outsider capturing the periphery for urban consumption, this is a territory in the periphery writing itself on its own terms.

Formally, the film embraces a light, sensory, almost tactile realism. Shots that linger, natural light, grain, edits that breathe with the characters, characters moving with and across each other. Nothing here tries to “aestheticize” poverty or exclusion — a common misstep when middle-class filmmakers depict the periphery. Ali, Aqui does not wish to elevate the neighbourhood into an aesthetic metaphor, but it wants to render it visible, alive, pulsating, complex, contradictory in all its layers. This is home.

And then there is politics. Always subterranean, never didactic, but omnipresent.

The politics of the father asking for wine for the cachupa, from the furthest store, so he can have a moment alone with the mother. The politics of a shop refusing to sell alcohol to the minor. The politics of unmaintained streets, shattered windows, and under-resourced schools. The politics of adult women — grandmothers — learning to read with the classic Chiquinho by Baltazar Lopes in hand. The politics of an informal settlement existing beside towers humming with gentrification. The politics of living with Lisbon within sight, working in Lisbon, but having it beyond true reach.

It is a Question of Politics

Housing and housing policy hovers over everything. In October 2025, residents of the Penajóia settlement — home to roughly 600 families — asked the Almada City Council to look at them as part of the solution, not as “a problem to be eliminated.” The same Almada municipality listed in the credits, alongside Terratreme, as co-producers of the community project that made this film possible.

Portugal has promised dignified, universal rehousing since the 1990s. Thirty years later, “temporary” has become intergenerational. Neighbourhoods stripped of the infrastructure available next door; precarious homes further precarized by municipal neglect and, in recent times, aggressive evictions; lives waiting for an envelope that never arrives. The pressure tightens over Penajóia — and it’s not by accident.

Housing speculation, private interests, and a securitarian logic move together in an old choreography: you push the most vulnerable further out of the city so the city can continue to grow, performing modernity, Europeanness, cosmopolitanism. The failures of housing policy in Portugal are not mere negligence; it is conceivably a failed design upheld by powerful political actors, including the mayors of Lisbon over the years (emphasis on the current one), as well as those of cities in its metro area. The film speaks of this Damoclean sword quietly, through the lives that move beneath it, capturing precariousness with the calm fortitude of those who have simply needed to live under it for decades. There is no sermon about exclusion. The streets show it with unmistakable clarity. No voiceover explaining inequality. But graffitied walls, activist posters, and a music-video set filled with neighbours who understand what is at stake.

The film’s greatest strength lies elsewhere, though: in how it moves across generations, linking the asylum’s past to the trajectories of young people in the projects; in how it follows friends teasing, laughing, hurting, reconciling; in how it tracks a boy on a simple errand — buying a bottle of wine for his father — that turns into an unintended odyssey through the multiple neighbourhoods coexisting in that small territory that is his world.

With a visually sophisticated grammar, the film repeats a leitmotif again and again: the distant towers, the southern pillar of the 25 de Abril Bridge, the Cristo Rei statue, the river below. It closes with two friends standing at the edge of the neighbourhood, on the edge of the valley, looking out toward distant Lisbon, one reciting a poem about Capeverdeanness — from here and there, from the diaspora and the old land — about what is lost and what remains. A poem that begins in there and ends in here. A poem that is, itself, a return.

As a film, Ali, Aqui offers recognition. In a historical moment when the far right grows by weaponizing housing insecurity, anti-poverty, anti-immigrant rhetoric, scapegoating communities masquerading as civic sport, citizenship wielded as a cudgel, this quiet film becomes a human bridge to a country that pretends it “could never have imagined” neighbourhoods like these, and which struggles to imagine them as dynamic, lived-in, dreaming spaces because television feeds it another picture altogether.

Cinema like this is indispensable — sensitive, revealing, necessary.

Ali, Aqui reminds us that entire countries are built in the interstices; that the South Bank of Lisbon is not “far away”; that there are communities writing themselves with fierce dignity. It reminds us, above all, that some lives pass daily through Lisbon’s line of sight without ever being actually being seen by/from Lisbon — even though, from their own window, Lisbon is always there, in the distance.

Credits and Notes:

2025 | Portugal | 70’

A film by: Daniela Mendes, Danty Alves, Fábio Lima, Jamir Mendes, José Monteiro, Marlene Nobre, Martina Maher, Milton Fernandes, Mónica André, Nelson Semedo, Paulino Varela, Rafael Moura, Rodrigo Galego, Edmilson Furtado tcp, Sony, Victoria Catarino

Cast: Clarisse Semedo, Crislyan Rafael Vieira, Daniela Mendes, Danila da Lomba de Melo, Filomena Moreno, Jamir Mendes, Mateus Pires, Matilde Semedo, Milton Fernandes, Nelson Semedo, Paulino Varela, Sony, Tofinha, Txidy Semedo

Camera Supervision: Luís Miguel Correia

Camera: Jamir Mendes, José Monteiro, Marlene Nobre, Martina Maher, Sony (Edmison Furtado), Victoria Catarino

Editing: Luís Miguel Correia

Sound Supervision: Nuno Carvalho

Sound Editing/Mix: Nuno Carvalho

Colour Correction: Paulo Menezes

Communication: Sara Folhas

produced in the framework of the community cinema project ATLAS ALMADA

Production Coordination: Raquel Rolim Batista

Production: Susana Nobre

Producer: Terratreme

Co-Producer: Câmara Municipal de Almada

World Première: DocLisboa Festival 2025

photos: courtesy of Terratreme