The places of youth in urban Cape Verde

As a result of an ongoing ethnographic research on youth, identity and citizenship in the port city of Mindelo[ii] (the second largest in the country, 70.500 hab.[iii]), in this paper I wish to describe and reflect about youth in Cape Verde in a double but complementary approach: 1) as a social metaphor in a rapidly changing political, cultural and economic context, 2) as a group of social actors who, within their diversity, reconstruct the forms of citizenship. Based on data collected from documental and academic sources, youths and adults’ interviews, direct and participant observation and a survey questionnaire (made to 197 young people between 16 and 35 years old in several educational and youth institutions of the city[iv]), I will try to describe and analyze how youth has become a strong social and symbolic category in the country and how young people presently fill their social places – old and new – and (re)construct their ways of being citizens in face of recent “crisis” and changes in the traditional ways of transition to the adultness and citizenship. Body, consumption, sexuality, expression, festivity, communality and informality will be analyzed as the central places of the new challenges, negotiations and innovations of citizenship of contemporary young people in Cape Verde.

As a result of an ongoing ethnographic research on youth, identity and citizenship in the port city of Mindelo[ii] (the second largest in the country, 70.500 hab.[iii]), in this paper I wish to describe and reflect about youth in Cape Verde in a double but complementary approach: 1) as a social metaphor in a rapidly changing political, cultural and economic context, 2) as a group of social actors who, within their diversity, reconstruct the forms of citizenship. Based on data collected from documental and academic sources, youths and adults’ interviews, direct and participant observation and a survey questionnaire (made to 197 young people between 16 and 35 years old in several educational and youth institutions of the city[iv]), I will try to describe and analyze how youth has become a strong social and symbolic category in the country and how young people presently fill their social places – old and new – and (re)construct their ways of being citizens in face of recent “crisis” and changes in the traditional ways of transition to the adultness and citizenship. Body, consumption, sexuality, expression, festivity, communality and informality will be analyzed as the central places of the new challenges, negotiations and innovations of citizenship of contemporary young people in Cape Verde.

Youth in Cape Verde

The major company of urban buses in Mindelo gives an interesting picture about youth through its set of price categories to the mensal bus pass: the least expensive category is “students”, for people form 6 until 18 years old; the second least expensive is “elderly people”, for people with 65 or more years old; the third is “youth”, concerning people between 19 and 25 and the fourth and more expensive is “funcionário” (meaning “employee”), for people over 25 years old. Although these categories evoke social statuses like student, youth or employee, the criteria adopted is simply age. This means that people under 18 can get a “student” pass even if they are not studying. And it also means that a student over 19 has to by a “youth” pass or even an “employee” pass if he or she is older than 25, being or not an employee. This is something that irritates a growing number of urban young people that continues (or restarts) studying after the age of 18 or even 25, most of them unable to find any kind of job that can cover their expenses (school fees, school material, food, cloth, bus pass, and sometimes even housing or children support).

The major company of urban buses in Mindelo gives an interesting picture about youth through its set of price categories to the mensal bus pass: the least expensive category is “students”, for people form 6 until 18 years old; the second least expensive is “elderly people”, for people with 65 or more years old; the third is “youth”, concerning people between 19 and 25 and the fourth and more expensive is “funcionário” (meaning “employee”), for people over 25 years old. Although these categories evoke social statuses like student, youth or employee, the criteria adopted is simply age. This means that people under 18 can get a “student” pass even if they are not studying. And it also means that a student over 19 has to by a “youth” pass or even an “employee” pass if he or she is older than 25, being or not an employee. This is something that irritates a growing number of urban young people that continues (or restarts) studying after the age of 18 or even 25, most of them unable to find any kind of job that can cover their expenses (school fees, school material, food, cloth, bus pass, and sometimes even housing or children support).

In Cape Verde, as well as generally worldwide, the category of youth is gaining salience and extension, both demographic, social, economic, political and symbolically. An extension however marked by the ambiguity on its content and its limits – who are the youths? when does youth end? – reflecting at the same time the ambiguities of contemporary social landscapes. Hence, as Debora Durham puts it: youth, as a historically constructed social category, as a relational concept, and youth as a group of actors, form an especially sharp lens through which social forces are focused on Africa, as in much of the world (2000:114). As social makers and breakers, (De Boeck and Honwana, 2005), as a lost generation or an innovative source of political power (O’ Brien, 1996), youth is bringing new social realities and new perspectives to social analysis in Africa. Marked by political exclusion, exploitation, war and violence, lack of education and job opportunities, emigration, influence of globalization and westernization of local culture, youth remake the symbolic dimension of personhood and agency (Durham, 2000:114) by informality and illegality, by violence and crime, by intimacy and sexuality, by innovative cultural expressions and social practices, forging new dimensions and uses of public space and citizenship (De Boeck and Honwana, 2005; Argenti, 2002; Diouf, 2003; Comaroff and Comaroff, 2005).

Cape Verde however, does not fit in the “typical” negative representation of an economical, political and culturally unstable African country. Achieving its independency from Portugal in 1975 and being under a single party socialist regime until 1991, the country registers remarkable post-independency developments on economy, democratic political institutions, public services and civil society organizations[v], achieving in 2008 the UN standard of Country of Medium Development. Being an ethnically homogeneous and mainly rural society, in the lasts decades Cape Verde has benefit from civic stability and peace, allowing international aid to generate good achievements on poverty reduction and infra-structures building. Nevertheless, especially after 1991, neo-liberal economic pressures and changes led to increasing external dependency, to the decrease on national production, to rapid and uncontrolled urbanization and to the growth of social inequalities (Laurent e Furtado, 2008). As consequences unemployment, urban poverty, precarious work and living conditions, alcohol abuse, violent crime and narcotraffic became generalized. Thus, in the last years cape-verdean society has developed a strong sense of social crisis and moral panic.

Young people appear in this context as strong social group and social symbol, as both symptoms and agents of social crisis. Adults tend to see contemporary young people as indolent, irresponsible, without objectives, vicious, incapable of effort and commitments, only interested on festivity and consuming, and even immoral, deviant, dangerous and criminals. Today’s adults often compared the present youth with their own post-independency generation, idealizing themselves back then as full of social and cultural objectives, national commitment and pride and strong sense of responsibility and effort to reach personal and social development. Facing contemporary transformations of (often idealized) traditional pardons of intimate and public relationships, of work and leisure, of consumption and savings, of expression and respect, today’s youth thus becomes a social metaphor for the unfulfilled social wishes and projects of the present adult generation.

Old places

But where do young people stand on contemporary Cape Verde? Taking into account the traditional and structural places of youth socialization and social integration – work, education and family – what stands out as their major characteristic are their present fragmentations and contradictions. Being a major demographic group (54.4% of Cape Verdeans are under 25 years of age and 70.4% are under 35[vi]), youth is nevertheless the most excluded social group from the field of formal labour. Young people are the most affected by unemployment (with un unemployment rate of 41,8% among the population between 15 and 24 years old[vii]) and the most expose to poverty and labour exploitation, recurring frequently to informal and precarious work to subsist economically. In fact, when asked about the greater obstacles they have to face to achieve their life objectives, unemployment (75,5%)* and poverty (67,2%)* are the ones on the top of the list.

Although in Education this level of exclusion seems no to occur, the field is also not free from contradictions. In the last three decades the country managed to supply full access to primary education and raise enormously secondary and higher education opportunities, thus raising young people and their families’ aspirations to achieve university degrees and their expectations of improvement of living conditions. But on the other hand, a general lack of quality of the educational offers and resources and its maladjustment to the local labour market led to a lack of job opportunities even to many of those with secondary or university degrees – something completely new in the cape-verdean society, where for the previous generation anyone with secondary or higher degree would easily get a job, especially on the public administration sector. Cape-verdean youths and their families are now becoming aware of these contradictions and are starting to develop a general critical and distrustful perspective on Education.

Finally, family appears to be a structurally and historically contradictory field in cape-verdean society, in tension between the ideal of romantic love and nuclear monogamic family, and the reality of extended and often transnational family networks, polygamy de facto and monoparental (frequently women led) households (Giuffrè, 2005; Rodrigues, 2002; 2005). For present cape-verdean youth, family stands also as an ambiguous place. It’s evident a growing intergenerational distance between adults and youths lifestyles and values, and at the same time the economical dependency of youth towards their adult family is extended in time. When asked about the most important things in their lives, young people clearly put family first. However, when asked about their expectations for the future, marriage is not mentioned as a priority and the expected number of children (2) mirrors the drastic reduction of national fertility rate in the last decades[viii]. Thus, if young people greatly value the family as an ideal, through their aspirations they also show its insecurity and retraction.

Transitions

In contemporary Cape Verde, youth status appears to be much wider in age and social situations than in the past. This is mainly due to a greater difficulty to access adult status via its traditional forms: getting a stable job, moving to an independent household or assuming a stable relationship (even if formal marriage was always an ideal rarely putted into practice in cape-verdean society). Although the majority of young people still state their wishes to achieve these goals (a job, a household, a family and even marriage)*, being adult (as opposite to youth) is frequently an undesired social status, associated with loss of intensity, joy, spontaneity and freedom. As a very spontaneous 18 years old boy said to me: you become adult when you start tucking your shirt on your trousers. Most young people clearly express the wish to be forever young and the average age that marks the transition to adultness is considered to be around 50 years old*.

Furthermore, in the cape-verdean society, the characteristics of youth and its symbols appear to be expanding and gaining social relevance also beyond the exclusive niches of young people. It seems revealing that in the small city centre it is possible to find a pharmacy, a barbershop and a driving school, all called “Jovem” (meaning “young”). Also, it is possible to witness a general tendency towards a “juvenilization” of different dimensions of urban social life, since, as several adult interviewees point out, there is a contemporary expanding tendency towards informality in the way – young and not so young – people talk nowadays, the way people dress, the way they move and the way they relate, even in working, religious, educational or other traditionally formal contexts.

It seems to remain a strong ambiguity between youth and adult status in contemporary urban Cape Verde. Both adults and youth interviewees referred that today’s young people do “adults things” too early in their lives – going out at night, experimenting alcohol and drugs, having sexual intercourse, being parents – but at the same time they have less access to adult prerogatives like housing, work and family responsibilities. Hence, the transition to adultness seems blurred and even meaningless, with young people frequently stating to be young and adults at the same time. Since adultness is based on responsibility and maturity and youth is based on a young spirit, dynamic, intense and joyful*, there is no contradiction in being both.

Responsibility stands out as the key dimension of this ambiguity. On one hand, adults tend to see youth as irresponsible and youths frequently agree with this representation and even reclaim a certain degree of irresponsibility. On the other hand, young people never see themselves personally as irresponsible and – internalising adult’s moral discourse on youth – they even consider responsibility an important characteristic of being young: responsible within their family, school, local community, leisure activities and sexual relationships. It appears as if through this ambiguous responsibility and status they fail to see – or they dissimulate – their subaltern place, their limitations and frustrations as forever young, forever unemployed or precarious employed, forever dependent on their family and forever engaged in uncommitted and superficial intimate relationships and parenting.

New places

On youth centres of distant suburbia areas of the city I could find some young people who helped me get a more complex and relative perspective on this ambiguous and subaltern youth status. I was able to get in touch with strongly engaged and active groups of young people, committed to the development of their communities and with a sharp sense of social inequalities. Discussing with them issues like social exclusion, citizenship or volunteering, they revealed a strong identification and solidarity with poor and excluded people – exclusion that they have felt themselves or witnessed very closely in their local areas. They also shown high motivation to participate in voluntary activities, such as cleaning campaigns, food distribution or house painting for poor families, free English or capoeira lessons and awareness raising activities about STD and alcohol or drug abuse. Some stated their motivation to engage in these activities in terms of “need to belong and to self-accomplishment”, “integrating in the society”, “expressing my ideas”, “showing my capacities” or “showing that I’m useful to society”, revealing a very concrete and personal link to volunteering, almost as a source of empowerment.

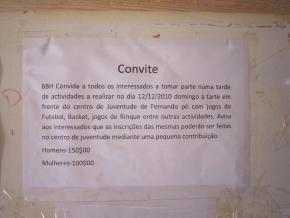

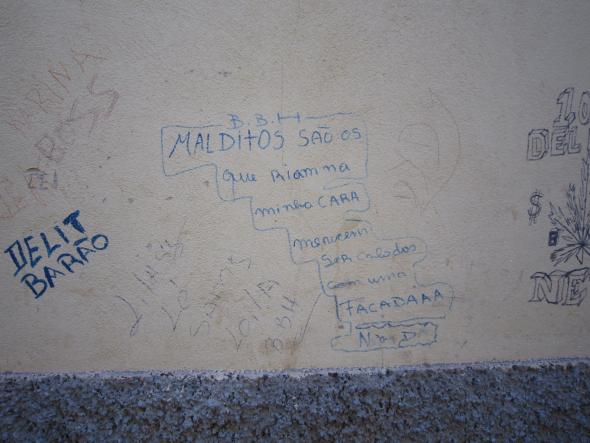

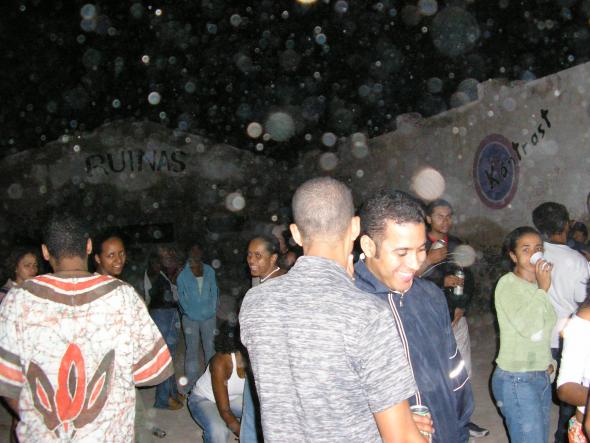

In fact, a majority of young people in the city (55,5%)* participate in some kind of youth group or association, mainly informal groups called “maltas” (approximately meaning “gangs” but without a violence or crime connotation), based on the area of residence in the city – or “zona”. These informal groups normally develop a high number of sport, cultural and community activities, such as volunteering and charity activities, football matches and other games, traditional dances shows, theatre plays and traditional or hip-hop music performances. Some of these groups promote contests and tournaments that involved several “maltas” from different “zonas” of the city or even from other islands of the country, promoting at the same time a sense of local pride and opportunities for geographical mobility. This is something highly valued by a majority of unemployed and out of school suburbia young people with few economic or professional chances to move within the city or the country and meet new people. These groups also frequently promote public performative activities such as “tardes de chá” (“tea afternoons”) with traditional music and dance, (female) beauty contests or dance parties, as ways to collect funds for their activities (especially connected with mobility or local charity). These public performances frequently involve important human and material community resources and, at the same time, manage to get social visibility and recognition for young people.

At both local and national levels, formal associative youth sector is weakly developed and often connoted with political parties’ interests. Even participating in youth groups, a great number of young people don’t find themselves represented by the formal youth sector nor do they see the need to constitute formal associations. On the other hand, many of the informal youth groups function internally with low levels of democratic leadership and participation and sometimes even with very formal, strict practices clearly borrowed from the traditional educational system. And if the ability of these groups to promote activities is remarkable, it is also impossible to ignore their general inability to develop critical social diagnosis and carry on with long term intervention projects or strategies.

At regional level formal youth structures are recently trying to promote the “formalization” of these informal youth groups and enhance their capacity to promote democratic leadership and project making. At national level, youth policy has developed largely in the past years, trying to coordinate and enhance social offers to young people: professional and technical training; entrepreneurial support and training; micro-credit information; vocational counselling and psychological support; creation of a youth card with discounts on school material, sports, communications and travel; information and training on birth control, STDs, alcohol and drugs; internet access; promotion of arts and sports, of youth associative structures and leisure times and volunteering activities.

At regional level formal youth structures are recently trying to promote the “formalization” of these informal youth groups and enhance their capacity to promote democratic leadership and project making. At national level, youth policy has developed largely in the past years, trying to coordinate and enhance social offers to young people: professional and technical training; entrepreneurial support and training; micro-credit information; vocational counselling and psychological support; creation of a youth card with discounts on school material, sports, communications and travel; information and training on birth control, STDs, alcohol and drugs; internet access; promotion of arts and sports, of youth associative structures and leisure times and volunteering activities.

Nevertheless, even is these efforts are having some important impacts on Mindelo’s youth in terms of access to information and training, they are still offered in a scatter and uncoordinated way and fail to reach and/or motivate a major number of young people that live far from the city centre and far from its formal sectors of education, public administration and business. In addiction, young people are clearly aware of the political instrumentalization underlying youth policies and centrally promoted youth activities and programmes (on volunteering, sports, arts, health) and understand that youth represents a (demographically massive) target to political parties, specially during electoral campaigns.

But if young people know they are political targets, they also know how to tactically take advantage of it. By exploring the financial or material support of every kind of governmental programme or political party, most of the times independently of its nature or political ideology, young people easily manage to gather important resources for their personal or professional lives and for their collective activities. Hence, political campaign periods fill the city with young people parading and distributing political parties’ t-shits and caps in exchange for cash, as well as with youthful events like hip-hop concerts, traditional dances or beauty contests, football matches and big pic-nic parties financed by political parties; hence, if any youth group wishes to organize a music concert or record a CD, promote a big regional camping or football tournament, it just has to pop the word “AIDS” somewhere and the national programme against AIDS will finance it; hence, every young person knows that to find a job more easily or secure its job when government changes, it’s better to enlist in whatever party is in power.

Although not as massive and powerful as in the previous single party socialist regime, partidary youth organizations still have some ability to attract and mobilize young people but, as some youths clearly state, mainly because they represent opportunities to gather resources and to establish personal connections and influences that can lead to prestigious positions. Nevertheless, even if this strategy can be used by some youths, it doesn’t represent the main perspective of young people on politics. Instead, politics is something they tend to undervalue and avoid, precisely because they feel national and local politicians are generally volatiles, opportunistic and unworthy of trust.

In this context it’s starting to grow especially among more educated youth and young adults a conscience that political and social action can be undertake outside the structures of political parties. Although fragile and not completely free from partidary influence, some local or national NGOs – like Red Cross, developing mostly around school teachers – are able to gather young people around social, environmental or cultural projects; and volunteering as well, has gained great expression and social value among youth. Also scouts and other religious youth groups continue to have an important presence, mainly within the Catholic Church, but also within a growing minority of Protestant and Pentecostal churches. If nowadays the Catholic Church is clearly losing its moral and ritual authority among youth, it’s also impossible to ignore its ongoing social, cultural and even political influence, since it has been, from colonial times until the present, an important context of youth education, conviviality, expression and social intervention.

Amateur theatre too has gained a strong relevance in the city, attracting more and more young people who freely engage in long and demanding training and preparation and, through several amateur groups, produce regular theatre plays and present them in noble public spaces with great acceptance and visibility. One of the main persons responsible for the development of amateur theatre in the city of Mindelo confirms this growing demand of young people and states that their main motivation is not social or political, but a search for personal development and an opportunity for expression. There is also a growing interest and recognition of the performing and expressive arts (theatre, dance, music, painting) in Cape Verde, and although there isn’t yet a local professional market of arts (with the exception of music), young people are starting to see them as future career possibilities.

While getting their own house is increasingly difficult and the family house becomes a narrow place to live, its opposed space – the street – becomes an important place for most of Mindelo’s youth. It’s frequent to ear adults say that young people nowadays just want paródia (“to party”), and even youths themselves think festividade (partying) is the major characteristic of cape-verdean youth (58,1%)*. In fact it’s not easy to miss the massive presence of youth on Mindelo´s central square – Praça Nova – and surrounding streets, especially at night. Taking over the city’s traditional ritual to have a evening promenade on the square, young people now ostensibly fill up this symbolic space until late hours at night, especially on weekends, with their youthful expressions: capoira performances, skate boards manoeuvres and car or motorbike speeding, drinks, sexy fashionable or gangster-rap outfits, last generation cell phones and MP3 readers, loud voices and laughter and flirts and intimidations between themselves or towards anyone that passes by. Whether it might be cape-verdean zouk or funaná, Brazilian funk or romantic songs, or some North-American Hip-hop or R&B hit, youth’ loud music is audible throughout the city, whether coming out from a slow driving car or bus on a central street, from the door of a neighbourhood bar-grocery-shop, from a concert on a night club or sports field, or from a dance party on a private rooftop.

Adults tend to see this ostensible use of public space as exaggerated and dangerous. This contemporary excessive partying is faced as an excessive freedom, lack of limits and absence of sacrifice spirit, potentially – and sometimes actually – leading to risk behaviours like school skipping, excessive spending, alcohol or drug abuse, unprotected sexual relations, and even theft or inter-gangs violence. Among adults stand out two kinds of justifications for this excess. On one hand, some tend to find on themselves the root of the problem. It were them who, having fought so hard – through studying – to escape the hardships of rural family work, consciously freed their children from that responsibilities and unconsciously promoted a generation to whom work and sacrifice are no longer structural values. On the other hand, adults also tend to think that the root of the problem is on the external influences of globalization: as if Brazilian soap operas, American movies and Hip-Hop music, the internet and all sorts of electronic and fashion consumer goods would lead a frailly educated youth of a peripherical country to adopt foreign models without adaptation or critique. In this way, at the eyes of some adults, youth excessive and dangerous behaviours appear as naive mimicry of the outside world.

Adults tend to see this ostensible use of public space as exaggerated and dangerous. This contemporary excessive partying is faced as an excessive freedom, lack of limits and absence of sacrifice spirit, potentially – and sometimes actually – leading to risk behaviours like school skipping, excessive spending, alcohol or drug abuse, unprotected sexual relations, and even theft or inter-gangs violence. Among adults stand out two kinds of justifications for this excess. On one hand, some tend to find on themselves the root of the problem. It were them who, having fought so hard – through studying – to escape the hardships of rural family work, consciously freed their children from that responsibilities and unconsciously promoted a generation to whom work and sacrifice are no longer structural values. On the other hand, adults also tend to think that the root of the problem is on the external influences of globalization: as if Brazilian soap operas, American movies and Hip-Hop music, the internet and all sorts of electronic and fashion consumer goods would lead a frailly educated youth of a peripherical country to adopt foreign models without adaptation or critique. In this way, at the eyes of some adults, youth excessive and dangerous behaviours appear as naive mimicry of the outside world.

Of course these two local justifications for the “problem of youth” are clearly limited, and adults too know this is only part of the story. As a local artist and social activist told me, globalization can only be negative when there is no mediation between the young person and the information. Nevertheless, the revealing aspect of these justifications is the fact that both stress social change – may it be from one generation to another, from tradition to modernity or from outside to inside – and both place youth as its central mediator. When I asked adults what they thought it would be important to research about youth, I got answers like “everything”, or “what is going on their minds”, or “what do they want”, “what do they have to say”, “what are their values”, “how do they see school and work”, “how do they see their future”. These answers are all about mediation, all about how youth is taking that role.

In order to start looking to young people minds, we can start by looking to their bodies instead. As several authors stress (Diouf, 2003; De Boeck and Honwana, 2005; Pais, 2005), the youthful body is the privileged place of mediation between personhood and social forces, the locus both for youth expression and subversion and for moral panic and social control. Urban Cape Verde is not an exception on this. It’s often through their bodies that boys and girls express their feelings, their wishes and their affinities, that they mange to negotiate their social statuses and even to find resources – material or human – to go on living the way they want to live. And it’s also through their bodies that morality and social control are sometimes defied, sometimes incorporated.

Even if in most contemporary cape-verdean youth, both boys and girls strongly exacerbate and sexualize their bodily figures, they do it in different ways. Female body, since colonial times until present day, continues to be the place were signs and ideals of race, social class and beauty interconnect to form subaltern or emancipatory configurations (Rodrigues, 2002). Many girls and young women that find themselves outside the path of higher studies and formal jobs, strategically manipulated these signs through the way they dress, the way they move or the way they use their bodies (on sexual relations, reproduction or informal work) to reconfigure their subaltern womanhood on a machist context and negotiate their gendered roles, at the same time trying to stay sexually desirable, emotionally attached and economically independent in relation to men (see also Massart, 2005; Grassi, 2003; Anjos, 2005). On the other hand it is also over the female body that lays the major social fears and moral discourses, linking health, sexuality, motherhood and responsibility. Facing male sexuality as “naturally” uncontrollable (Guiffrè, 2005), it’s generally “natural” in Cape Verde to point all evils to girls and demand to them all the responsibilities related to sexual harassment, STD prevention, birth control, adolescent pregnancy and parenting – and to focus on them all health and educative campaigns, programmes or laws on these issues. Such is the case of a 2001 dubious disposition of the Ministry of Education that allows high school boards to temporarily suspend pregnant students until they deliver their child, on the grounds that this suspension period allows young girls to fully assume their motherhood duties. But not all cape-verdean society, including many young people, seems to think of motherhood on such “natural” terms and since its implementation the debate is intense on this and other related topics of women and youth rights and morality.

Even if in most contemporary cape-verdean youth, both boys and girls strongly exacerbate and sexualize their bodily figures, they do it in different ways. Female body, since colonial times until present day, continues to be the place were signs and ideals of race, social class and beauty interconnect to form subaltern or emancipatory configurations (Rodrigues, 2002). Many girls and young women that find themselves outside the path of higher studies and formal jobs, strategically manipulated these signs through the way they dress, the way they move or the way they use their bodies (on sexual relations, reproduction or informal work) to reconfigure their subaltern womanhood on a machist context and negotiate their gendered roles, at the same time trying to stay sexually desirable, emotionally attached and economically independent in relation to men (see also Massart, 2005; Grassi, 2003; Anjos, 2005). On the other hand it is also over the female body that lays the major social fears and moral discourses, linking health, sexuality, motherhood and responsibility. Facing male sexuality as “naturally” uncontrollable (Guiffrè, 2005), it’s generally “natural” in Cape Verde to point all evils to girls and demand to them all the responsibilities related to sexual harassment, STD prevention, birth control, adolescent pregnancy and parenting – and to focus on them all health and educative campaigns, programmes or laws on these issues. Such is the case of a 2001 dubious disposition of the Ministry of Education that allows high school boards to temporarily suspend pregnant students until they deliver their child, on the grounds that this suspension period allows young girls to fully assume their motherhood duties. But not all cape-verdean society, including many young people, seems to think of motherhood on such “natural” terms and since its implementation the debate is intense on this and other related topics of women and youth rights and morality.

Male bodies are also places of identity, expression and social fear. However, if with girls the key feature is sensuality, for boys it seems to be more about bodily performance. Many boys and young men outside the formal sector of education and work – but not exclusively those – ostensibly cultivated their bodies on a growing number of gyms or publicly on the city beach. These high performance bodies are then paraded on public spaces, sports and night clubs, both fearfully – through aggressive behaviour and violence – and attractively – through sexualized moves and poses. Yet public signs of affection or intimacy towards girls are seldom seen. It seems as if these boys, through their body strength, strive to maintain some of the traditional masculine power that is being taken from them by their ongoing marginality, unemployment and dependency and by present female social emancipation (Massart, 2005; Anjos, 2005). For boys the body is clearly a place of expression of angst and rage and a way to conquer – by force – new social spaces.

Male bodies are also places of identity, expression and social fear. However, if with girls the key feature is sensuality, for boys it seems to be more about bodily performance. Many boys and young men outside the formal sector of education and work – but not exclusively those – ostensibly cultivated their bodies on a growing number of gyms or publicly on the city beach. These high performance bodies are then paraded on public spaces, sports and night clubs, both fearfully – through aggressive behaviour and violence – and attractively – through sexualized moves and poses. Yet public signs of affection or intimacy towards girls are seldom seen. It seems as if these boys, through their body strength, strive to maintain some of the traditional masculine power that is being taken from them by their ongoing marginality, unemployment and dependency and by present female social emancipation (Massart, 2005; Anjos, 2005). For boys the body is clearly a place of expression of angst and rage and a way to conquer – by force – new social spaces.

In face of an escalade of (a highly media magnified representation of) urban youth violence and crime – sharply contrasting with the nation imaginary and rhetoric of peaceful country – it’s not surprising then, that the military, the police and the private security sector are growing job opportunities for boys. Demanding low educational qualifications and offering a market in expansion, they show a clear mirror image of a society with little to offer to its youth but to put them fighting each other in order to dissimulate a growing social crisis.

Youth as citizenship

Several authors (Giddens, 1997; Muggleton, 2000) point to the fact that, facing contemporary social fragmentation and uncertainty, the debates and the demands around citizenship tend to retract to the personal level of lifestyles, intimate relations and identities expression. Other authors (Cole and Durham, 2007; Yanagisako and Collier, 1991) reveal that intimate relations mirror macro-social structures and forces, both shaping and being shaped by them. Hence, it’s possible to argue that personal expressions are acts of citizenship not only because there are public acts, but also because they reveal larger social forces and tensions and they suggest social changes, even if not fully conscious or fully understood. As a Portuguese sociologist puts it, expression is nothing more then a pressure that comes out (Pais, 2005: 62).

As argued above, whether by prolonged unemployment or by inability to establish independent households and stable intimate relationships, by inadequate or ineffective educational opportunities or by political under representation and disaffection, in urban Cape Verde an important part of young people is largely excluded from the traditional places of social belonging and social action – work, family, education and partidary politics. Out of these places of both adultness and formal citizenship, young people are compelled to marginal spaces to continue being able to demand rights and exert duties, to belong – or to wish to belong – to groups or communities and to act upon their social context.

Through performative arts and performative bodies, through informal work and informal groups, through solidarity actions and festive moments, through sexual relations and violent behaviours, through tactical political or religious instrumentalization, on central city spaces and on distant suburbia “zonas”, young people build new places and signs – a culture? – that, more than resistance, it’s a claim of an existence not always subject of social recognition (cf. Honneth, 1997, cit. in Pais, 2005). It’s through these places and these signs that contemporary cape-verdean youth expresses its pressures, its wishes, its frustrations or its imagined alternatives. It’s how they mediate between exclusion and inclusion, past and future, tradition and modernity, local and global, social inequalities and personal aspirations; how they search new experiences of personal accomplish and social recognition. And in so doing, they build new places for their subjectivities and agency, for their ways of being in the world.

Youth exclusion form the abstract and “adultocentric” language of civic, economical or social rights of formal citizenship (Cf: Castro, 2001 in Pais, 2005), makes them create new forms of expression that demand new signs and new places. These signs and these places are often faced by adults – and even by young people themselves – as simply “youthful”, and they are undervalued by that. But, as I have also tried to show, these signs and places of youth are expanding in cape-verdean society, both in age range and through different social fields. The languages of youth – of intensity, freedom, informality, festivity, irresponsibility, sensuality and violence – is entering not only on public spaces and leisure times, but also on formal sectors like work, family, education, religion and politics. Even if, as a group of social actors, youth is economic and politically powerless, youth as a social metaphor, as a symbol, is conquering social space in urban Cape Verde.

Therefore, with the blurring of limits between youth and adultness and the social generalization of youthful signs, it appears that everyone can be young at Cape Verde nowadays. And with the shrinking of the formal spaces of citizenship and the growing social exclusion, it also appears that most of cape-verdeans – young or not so young – do want to become youths. Not because it’s better to be young, but because to be youthful seems the only way to find a new place of “ex-pression”. Thus, youth becomes a new lexic of belonging, of demanding and of acting; an expanding way to become citizen. Not the only one, of course, but an appealing one on neoliberal contemporary Cape Verde.

References

ANJOS, José C. G. dos (2005), “Sexualidade Juvenil de Classes Populares em Cabo Verde: Os Caminhos para a Prostituição de Jovens Urbanas Pobres”, Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, 13(1): 163-177.

ARGENTI, Nicolas (2002), “Youth in Africa: a major resource for change”, in de Waal, Alex, Nicolas Argenti (eds.), Young Africa. Realising the rights of children and youth, Trenton and Asmara, Africa World Press, 123-153.

COLE, Jennifer & Deborah DURHAM (2007). “Age, Regeneration and the Intimate Politics of Globalization”. Generations and Globalization. Youth, Age and Family in the New World Economy. (Ed.) Jennifer Cole & Deborah Durham. Bloomington, Indiana University Press: 1-28.

COMAROFF, J. & J.L. COMAROFF (2005), “Reflections on Youth from the Past to the Postcolony”, Makers and Breakers. Children & Youth in Postcolonial Africa. (Ed.) Alcinda Honwana & Filip De Boeck. Oxford, Trenton and Dakar, James Currey, Africa World Press and CODESRIA: 19-30.

DE BOECK, Filip & Alcinda HONWANA (2005). “Children & Youth in Africa. Agency, Identity &Place”, Makers and Breakers. Children & Youth in Postcolonial Africa. (Ed.) Alcinda Honwana & Filip De Boeck. Oxford, Trenton and Dakar, James Currey, Africa World Press and CODESRIA: 1-18.

DIOUF, Mamadou (2003). “Engaging Postcolonial Cultures: African Youth and Public Space”, African Studies Review 46(1): 1-12.

DURHAM, Deborah (2000). “Youth and the social imagination in Africa: Introduction to parts 1 and 2”, Anthropological Quarterly 73(3): 113-120.

GIDDENS, Anthony (1997) [1991], Modernidade e Identidade Pessoal, Oeiras, Celta Editora.

GIUFFRÈ, Martina (2005), “Being a woman in Ponta do Sol: renegotiation of Cape Verdean Women Identity trough the ‘Prism’ of the Outside World”, Personal Communication at the International Conference on Cape Verdean Migration and Diaspora, Lisboa, CEAS-ISCTE.

GRASSI, Márcia (2003), Rabidantes. Comércio espontâneo transnacional em Cabo Verde, Lisboa, ICS.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA (2010), Resultados preliminares do Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação 2010, Praia. [em linha ]. Disponível em www.ine.cv/ [consultado em 09/11/2010]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA (2007), Questionário Unificado de Indicadores de Bem Estar, Praia. Disponível em www.ine.cv/ [consultado em 01/07/2008].

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTATÍSTICA (2004), Perfil Demográfico, Socio-económico e Sanitário de Cabo Verde, Praia. Disponível em www.ine.cv/ [consultado em 29/05/2008].

LAURENT, P.J.; FURTADO, C. (2008), “A Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus de Cabo Verde: Crescimento urbano, pobreza e movimento neopentecostal”. Revista de Estudos Cabo-Verdianos, , no.2: 31-54.

MASSART, Guy (2005) “Masculinités pour tous? Genre, Pouvoir et Governementalit´r au Cap-Vert”, Marissa Moorman and Kathelen Sheldon (Ed.) Lusotopie. Gênero e Relações Sociais, Leiden and Boston, Brill.

MUGGLETON, David (2000), Inside Subcultures: The Postmodern Meaning of Style, Oxford, Berg.

PAIS, José Machado (2005), “Jovens e Cidadania”, Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas (49): 53-70.

RODRIGUES, Isabel P. B. Fêo (2002) “Chapter IV. Creole Tensisons. Intersecting Race, Class and Gender” in Crafting Nation and Creolization in the Islands of Cape Verde, PhD. Thesis, Princeton, Rhode Island, Department of Anthropology at Brown University.

RODRIGUES, Isabel P. B. Fêo (2005) “’Our ancestors came from many bloods’. Gendered narrations of a hybrid nation”, Marissa Moorman and Kathelen Sheldon (Ed.) Lusotopie. Gênero e Relações Sociais, Leiden and Boston, Brill.

YANAGISAKO, Sylvia and Jane Collier (1991) [1987], “Toward a unified analysis of Gender and Kinship”, Jane Collier and Sylvia Yanagisako (Ed.), Gender and Kinship. Essays Towards a Unified Analysis, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

[i] PhD student in Anthropology at ISCTE - Lisbon University Institute, Researcher at the Centre for Research in Anthropology and Centre for African Studies, University of Porto (Portugal); filipemartins79@gmail.com

[ii] A first version of this paper was presented at the CODESRIA Symposium on Gender and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization, 80-10 October 2008 in Cairo, Egypt. It was subsequently published in the Minutes of the Sixth International Congress for Research and Socio-cultural Development, AGIR; Melide, Spain, 23-25 October 2008.

[iii] Source: Preliminary results of the Census of Population and Housing 2010, INE, 2010.

[iv] It was taken as reference for youth people between 15 and 35 years of age, in line with that indicated by the Government of Cape Verde in the document Council of Ministers Session Dedicated to Youth: Strategic Document, Praia, 2002.

[v] For an overview of the evolution of these indicators see the profile of Cape Verde at World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/country/cape-verde?display=graph accessed at Nov. 9, 2010) and African Development Bank Group (http://www.afdb.org/en/countries/west-africa/cape-verde/ accessed at Nov. 9, 2010).

[vi] Source: Preliminary results of the Census of Population and Housing 2010, INE, 2010.

[vii] Source: Unified Questionnaire on Welfare Indicators, INE, 2007.

[viii] 7 children per woman in 1974, 3.7 children per woman in 2000, 2.7 children per woman in 2009. Source: World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN/countries/1W-CV?display=graph access at Nov. 9 2010).

* Results of the survey questionnaire.