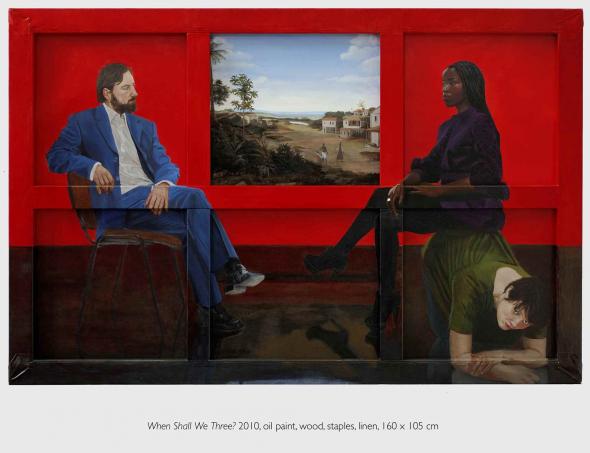

Queens of the Undead, an exhibition of Kimathi Donkor

'When Shall We Three?' Rainha Nzinga by Kimathi Donkor The first time I saw Rainha Nzinga of Matamba, I was walking across Luanda’s Kinaxixi square with a friend. We stopped to admire the vast bronze tribute to the seventeenth-century Mbundu monarch, who not only fought Portuguese armies, but caused consternation among her own people and played a significant role in developing the Angolan slave trade. I was immediately impressed by the statue, although my friend, an Angolan journalist, was less so. ‘In real life, you’d have seen her breasts,’ he said, ‘but they’ve been covered up to appease our modern sensibilities.’

'When Shall We Three?' Rainha Nzinga by Kimathi Donkor The first time I saw Rainha Nzinga of Matamba, I was walking across Luanda’s Kinaxixi square with a friend. We stopped to admire the vast bronze tribute to the seventeenth-century Mbundu monarch, who not only fought Portuguese armies, but caused consternation among her own people and played a significant role in developing the Angolan slave trade. I was immediately impressed by the statue, although my friend, an Angolan journalist, was less so. ‘In real life, you’d have seen her breasts,’ he said, ‘but they’ve been covered up to appease our modern sensibilities.’

An even more contemporary rendition of Nzinga is currently on display at Rivington Place, an international visual arts centre in London. In an exhibition called Queens of the Undead, 47-year-old British artist Kimathi Donkor portrays the pivotal Angolan heroine in all her complexity. In one painting, we see her talking on a mobile phone whilst fingering the hair of a transvestite male carrying an AK47; in another, she’s wearing black leggings and wedged stiletto shoes whilst sitting on the back of a kneeling white woman and talking to a Portuguese governor in a twenty-first-century suit; and in another, the formidable female ruler is riding fiercely on a motorbike whilst staring out of the canvas straight into our gaze.

Donkor fills his large oil paintings with garish colours — scarlet red, bright blue, purple and even a ghastly, girlish pink — creating arresting works of art that implore you to stop, and look, and think. And then, to think again. For there is something familiar in all of his portraits, an uncomfortable quality that draws the viewer into the painting.

'Drama Queen' Rainha Nzinga by Kimathi Donkor

'Drama Queen' Rainha Nzinga by Kimathi Donkor

As well as Nzinga, Queens of the Undead includes imaginary scenes featuring three other historic and heroic women: Nanny of the Maroons, the eighteenth-century Ghanaian-born Jamaican slave who led a series of slave rebellions; Harriet Tubman, a nineteenth-century African-American who was born into slavery but later freed herself and became a leading abolitionist; and the Ghanaian Yaa Asantewaa, who led the Ashanti rebellion against British colonialism in 1900.

Donkor’s paintings riff off well-known classical works — such as ‘The Martyrdom of St Matthew’ by Caravaggio (1600) and ‘Jane Fleming’ by Joshua Reynolds (1778) — to create new portraits of these heroic figures from Africa and the black African diaspora. His technique of détournement is borrowed from the French Marxist thinker, Guy Debord, who sought to challenge the capitalist system and its media culture by turning its images back on themselves. In Donkor’s case, the twist in his paintings serves to undermine the idea of racial supremacy and white European domination.

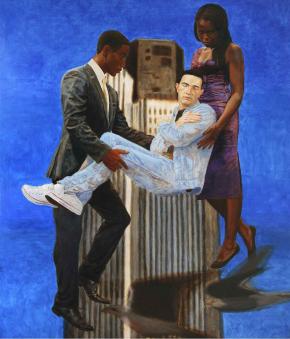

Johnny was borne aloft by Joy & Stephen (2010)This theme continues in the other half of the exhibition, which presents three more paintings, each depicting contemporary scenes of British police brutality and racism. So, for example, in Johnny was borne aloft by Joy & Stephen, we see the body of Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian man who was shot dead by police in London in 2005. Mistaken for an alleged terrorist, he was killed two weeks after the London bombings in which 52 died in a series of co-ordinated suicide bombings. In Donkor’s painting, de Menezes’ body resembles Caravaggio’s depiction of Jesus in ‘The Entombment of Christ’ (1603). However, here, it is being carried by Joy Gardner, a Caribbean woman who died after police raided her home in London in 1993, and Stephen Lawrence, the black British teenager who was murdered in a racist attack the same year.

Johnny was borne aloft by Joy & Stephen (2010)This theme continues in the other half of the exhibition, which presents three more paintings, each depicting contemporary scenes of British police brutality and racism. So, for example, in Johnny was borne aloft by Joy & Stephen, we see the body of Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian man who was shot dead by police in London in 2005. Mistaken for an alleged terrorist, he was killed two weeks after the London bombings in which 52 died in a series of co-ordinated suicide bombings. In Donkor’s painting, de Menezes’ body resembles Caravaggio’s depiction of Jesus in ‘The Entombment of Christ’ (1603). However, here, it is being carried by Joy Gardner, a Caribbean woman who died after police raided her home in London in 1993, and Stephen Lawrence, the black British teenager who was murdered in a racist attack the same year.

What is refreshing about Donkor’s work is its unashamed political vigour. His paintings raise critical questions about memory and myth, forcing us to reflect on the continuities between contemporary times and our colonial and pre-colonial histories. What makes them even more poignant in a London gallery — one that was designed by the British-Ghanaian architect David Adjaye — is their rarity. Despite this city’s cosmopolitan character, it is not often in major galleries that we see black people depicted as courageous and complex protagonists, and white policemen as perpetrators of violence. I only wish my Angolan friend, the journalist who introduced me to Rainha Nzinga, were here to look at them too.

África 21/22 October 2012