Black archetypes and stereotypes in brazilian films

from the book Afrobrazilians in brazilian films (Pallas, Rio de Janeiro, 3rd edition 2012)

by João Carlos Rodrigues

A frequent charge made about Brazilian cinema by Black intellectuals and artists is that the films do not present truly individualized characters, but rather mere archetypes and/or caricatures. The accusation is pertinent, since Brazilian cinema generally favors character-types, schematic or symbolic, Black or not.

A frequent charge made about Brazilian cinema by Black intellectuals and artists is that the films do not present truly individualized characters, but rather mere archetypes and/or caricatures. The accusation is pertinent, since Brazilian cinema generally favors character-types, schematic or symbolic, Black or not.

In Black folklore in Brazil (1935), anthropologist Artur Ramos observed that orishas (African deities) “passed into Brazilian folklore and maintain close contact with the popular imagination, a magical and somewhat familiar contact, since they survive as symbols of individual complexes”. They appear as much in ancestral African religions (Candomblé), as in the Brazilian religion Umbanda, which absorbed other influences (e.g., indigenous, oriental). [See the documentary Santo forte, Eduardo Coutinho, 1999 where normal people dialogue daily with supernatural entities.] These symbols are amply detailed in the book Orishas (Pierre Fatumbi Verger, 1981) where a classification of the personal qualities and defects of Afro-Brazilian divinities details more than a dozen diversely human personalities

Of more recent extract, another family of types comes from the white imagination, variously forged from fear, solidarity, love, or hate. Many arise from slavery; others are still in formation today in the Brazilian collective unconscious - similar to archetypes found in the United States and Cuba. Not all are pejorative.

Inspired by the play The blacks: A clown show (Jean Genet), Verger’s work, and based on my own observations, I established a subdivision of archetypes and caricatures of Blacks in Brazilian cinema. In Brazilian fiction, in or beyond cinema, all Black characters pertain to or are a mixture of one or more of the following categories.

Pretos Velhos [Old Blacks]

Typical of this mixture of diverse, cultural subtracts. They descend from West African griots and akpalô who maintained tribal oral tradition through stories, legends, and genealogies. Brazilian folklore also offers Histórias de Pai João e Mãe Maria from the slavery era, narrating, with resigned irony, the master-slave relationship, similar to Uncle Remus: Legends of the Old Plantation (Joel Chandler Harris, 1881) in the United States, transformed by Walt Disney into Song of the South (1946).

Old Blacks of both sexes are frequent entities in Umbanda religion, but Candomblé also attributes many of the characteristics (wisdom, indulgence, dignity) to the elderly sea goddess, Nananborocô and the aged Oxala (Oxalufã).

Another important contribution to the construction of this archetype includes literary characters. The most popular is Auntie Nastacia from the children’s collection O Pica-Pau Amarelo (Monteiro Lobato, 1921), adapted many times for television and on film. She is nice and generous, but basically ignorant and superstitious.

Despite their illustrious origins, Old Blacks appear in Brazilian fiction as essentially conformists, and seldom appear in Brazilian cinema where they would never be more than supporting players.

Mãe Preta [Black Nanny-Mammy]

That’s an archetype that originates from Brazilian slavetocracy where the white owner’s son was typically nursed by a Black wetnurse. She is customarily presented as suffering and conformist, similar to the Old Blacks.

The play Mãe (Jose de Alencar, 1860) broaches the theme of one of these self-sacrificing beings, who prefers suicide to being a hindrance to the marriage prospects of her natural child. This is the same atrocious suffering of Mamãe Dolores in O direito de nascer, a Cuban radio soap opera written by Felix Caignet in the 1940s and filmed in Mexico in 1951 and 1966. A huge success in Brazil, it was re-released on national radio and adapted three times for television and once for film.

The subtext is evident: in order to be fully accepted by dominant society, these children must renounce their Black nannies, who only offer a past best left forgotten. If the former charges are unable to do this, the nannies - clearly recognizing their place on the lowest rung of society - abdicate their rights in order to not adversely impact them. A character steeped in melodrama, the Black Nanny-Mammy is very frequent in television soap opera.

Black Martyr

Another archetype that always appears in fiction dealing with slavery, reflecting the tyranny and sadism of some landowners and overseers, whose excesses have been mythologized in local lore: O Negrinho do Pastoreio is a Black-shepherd boy, whom, after losing the owner’s livestock, is tied to an anthill and devoured alive; and, since 1980, Escrava [Slave] Anastacia has been transformed by popular belief into the representation of a fictitious, miracle-working (blue-eyed) slave woman, tortured to death for insubordination and erroneously tied to an eighteenth century engraving by the Dutch [artist] Rugendas. Despite the Catholic Church’s opposition, her faithful grew unchecked and today Anastasia is worshipped throughout the country.

Xica da Silva (1976)

Xica da Silva (1976)

Negro de Alma Branca [literally Blackman with a white soul]

It represents a Black who received a good education and because of it was (or wanted to be) integrated into dominant society.

An historic example is Francisca da Silva - eighteenth century ex-slave, mistress of a high official of the Portuguese crown in Minas Gerais - who fought to integrate herself into society. She was immortalized in the popular imaginary by the Salgueiro Samba School, popular songs, and by the box office hit Xica da Silva (Carlos Diegues, 1976).

At other times, o Negro de Alma Branca appears as a rootless intellectual, alienated from his humble beginnings and equally rejected (or ridiculed) by whites. The protagonist of the novel O mulato (Aloisio Azevedo, 1881) is typical. Intellectually superior to his white rivals, Raimundo is rejected by the provincial society of Maranhão. In an important and little known film, Também somos irmãos (José Carlos Burle, 1949), the protagonist lawyer soundly typifies this archetype.

For many, the typical Negro de Alma Branca would be (Mulatto) Machado de Assis (1839-1908), Brazil’s greatest writer. Despite growing up in a lower-class background, his extensive writings practically ignore the Afro-Brazilian world in which he was formed. Such too is the case of Jorge, a journalist in the film Compasso de espera (Antunes Filho, 1973) who, alienated from both worlds, lives in limbo and uncertainty.

Films starring famed soccer player Pelé offer similar storylines: an exemplary boy becomes a great athlete in the biographical O rei Pelé; a Black freeman dissuades slaves from employing violence in their fight for freedom in A marcha; a well-intentioned policeman protects street children from a terrible gang in Os trombadinhas. Pelé ´s didactically “positive” characters are always far removed from the daily reality of the overwhelming majority of Black Brazilians.

Noble Savage

From the era of Brazilian colonization, the Noble Savage seems to originate from the story of the Three Kings, one of whom (Balthazar) was represented in Catholic iconography as a Black, after the “discovery” of the Christian Coptic Realm in Ethiopia. He possesses the dignity, respectability, and fortitude attributed by Verger to the young Oxalá (Oxaguiã). He is not a conformist like Pai João, nor ambiguous like the Negro de Alma Branca. Brazilian cinema has many characters with these characteristics, for example, Carlos Diegues’s two films which deal with the runaway-slave settlement Palmares.

In Ganga Zumba (1964), during the flight from captivity, the son of the African king loses interest in his former companion after meeting Dandara, a Black princess who is his “equal”. In Quilombo (1985), Zumbi is chosen leader by God himself who sends a fiery spear from the heavens. In the first case, the union of the upper classes reflects social allegiances evident in slavetocracies. In the second, the leader is a superhuman being - superior not only to other slaves, but to the rest of humanity as well.

In Chico rei (Walter Lima Junior, 1985), inspired by an eighteenth century legend, the attitude of the protagonist is completely reversed. Here, the leader, imprisoned with his tribe, works in the gold mines to buy his liberty, then that of his subjects, in a beautiful lesson about solidarity.

Black Militant

It is a bellicose variation on the Noble Savage. Unsurprisingly, one of the first literary works about him, the novel Bugh Jaghral (Victor Hugo, 1883), was inspired by historic figures (Toussaint L’Ouverture, Dessalines) from Haiti, the first Black country to achieve its independence (1804).

Brazil’s greatest Black Militant was Zumbi, last king of the Palmares settlement whose inhabitants resisted Portuguese colonists for almost the entire seventeenth century. Today his semi-legendary saga is taught in schools and, as a national/popular hero, he is the topic of songs, plays, television series, and films.

The many examples of traditional films about the period tell of a flight from the plantation, generally after the assassination of the evil overseer who brutalized an innocent. This is the storyline in Sinhá moça (1953) and A marcha (1972). However, as in the bible, the entry into the Promised Land is not open to all. In Ganga Zumba, the diseased and “impure” are executed at the gates of Palmares. In Quilombo, the director describes how a mercantile society, pressured by a more powerful adversary, becomes so militarized that it invites its own self-destruction. In all these films, the settlement is a political utopia, and the Black Militant, an idealist destined to fail.

The contemporary equivalent of the runaway settlement appears in the play Sortilégio (Abdias Nascimento, Teatro Experimental do Negro, 1957). Emmanuel, a lawyer, kills his white wife in a fit of jealousy and flees, pursued by the police. During his flight, he leaves behind his white veneer, acquiring consciousness of his Blackness, proclaiming “I am Black, free from the niceties of white civilization”.

Nothing so explicit or so blunt exists in Brazilian film where everything occurs in a decidedly more modest tone. Chico Diabo in A grande feira (1961), a small-time delinquent, attempts to burn down an oil refinary but is captured and delivered to the police by the masses. Of more consequence is Firmino in Barravento (Glauber Rocha, 1962): fresh from the metropolis, he enters into conflict with the backward Black fishermen. In the end, he is personally defeated, but politically victorious, since he undoes the superstitions that enabled economic submission. Among the supporting roles in Compasso de espera, there is a more sophisticated, cosmopolitan militant, influenced by Marcus Garvey and Kwame Nkrumah, suggesting a very subtle evolution in this archetype.

Negão [Black Stud]

Historically, aberrant or insatiable sexual appetites have been attributed to Blacks. The resulting archetype, the Negão [Black Stud] possesses the sensuality and violence attributed to Candomblé’s Eshu, associated with the devil by Catholic clergy. He is the bloody rapist, terror of all fathers, the social avenger. When in love, he can be tender. Rejected, he becomes a beast. He is sexually ambiguous, at times displaying markedly homosexual characteristics or the bisexuality of orisha Logun-Edé who is alternately male then female for six months each.

In the novel The sailor and the cabin boy/Bom Crioulo (Adolfo Caminha,1895), seafarer Amaro falls in love with a white apprentice and, when abandoned, avenges himself by stabbing him to death. The protagonist of A rainha diaba (1975), an interesting film by Antonio Carlos Fontoura, encarnates the range of bourgeois anxiety: he is at once a drug trafficker, killer, homosexual, and Black. Madam Satan (2003) is all of this as well; he, however, fights to be accepted by society. The classic gay-porn Island Fever (Kristen Bjorn) presents typical examples of the Black Stud as a homosexual symbol, with penis and appetites of exaggerated proportions.

The Black Stud might well be the burning desire of depraved teenagers. Bonitinha, mas ordinária, a play by Nelson Rodrigues adapted twice for film (1963, 1980), features a protagonist who wants to be (and is) gang-raped by blackmen. In the novel Terror e êxtase (José Carlos de Oliveira, 1978), a beautiful middle class nymph falls in love with her kidnapper, a poor, toothless Black. The cinematic version (1980) smoothed the racial impact of the plot. In A menina e o estuprador (1983), manipulating possible audience prejudice, Conrado Sanchez depicts a guilty Black protagonist, later proven innocent. The film’s poster, showing a nude Black man embracing an equally nude beautiful adolescent white female, is a rarity in Brazilian advertising.

Quilombo (1984)

Quilombo (1984)

Malandro [(Black) City Slicker]

More frequently represented as a Mulatto, the Malandro is one of the better documented archetypes. Classified in Umbanda as the devilish Zé Pelintra who wears the typical white suit and straw hat of the tropical pimp, this character also combines the characteristics of Candomblé orishas: ambivalence and double-dealing (Eshu); instability and eroticism (Chango); violence and sincerity (Oggun); and, mutability and cunning (Ossosi).

Early on, Malandros appear as well-defined mixed-race figures in literature: Chico Juca in Memórias de um sargento de milícias (Manuel Antonio de Almeida, 1853), Firmino in O cortiço (Aluisio Azevedo, 1890), and Ricardo in Coração-dos-Outros: de Triste fim de Policarpo Quaresma (Lima Barreto, 1916).

In popular music, the Malandro is a type immortalized since the 1930s in the sambas of Moreira da Silva, Wilson Batista, Geraldo Pereira, Zé Kéti, Bezerra da Silva, Almir Guineto, Beto-Sem-Braço and Zeca Pagodinho.

Historically, the Malandro became a popular character in burlesque (Forrobodó, Luiz Peixoto and Chiquinha Gonzaga 1912). In the 1950s, three importance dramatic works featured him: Pedro Mico (Antonio Callado), Gimba (Gianfrancesco Guarnieri), and O Boca de Ouro (Nelson Rodrigues). All were adapted for the screen. In the first two, the likeable-enough character is artificially idealized and the authors seem bent on proving a socio-political point rather than developing a fluent dramaturgy. In the stage productions, white actors play the roles, “blackened” with make-up. In the cinematographic adaptations, only Pedro Mico featured a Black actor.

Cinema was equally fascinated by the Malandro. In 1908, the pioneering Antonio Leal produced Os capadócios da Cidade Nova which advertized “serenaders, capoeira, and Malandros”. In 1917, A quadrilha do Esqueleto promised “the ins-and-outs of the Malandro lifestyle” and non-professional actors. It is mind-numbing that Black and Mulatto actors participated in these films of which sadly no prints exist. Two adaptations of O cortiço were filmed (1945, 1978) which were basically faithful to the novel, a Naturalist sketch of nineteenth century social classes.

Over time, the classic Malandro, elegantly interpreted by Grande Otelo in Amei um bicheiro (1952) and Três vagabundos (1953), was replaced by others of more marginal ilk. Adolescents with limited prospects in Bahia de todos os santos (1960) live from odd-jobs, contraband, pimping, and petty larceny. Chico Diabo in A grande feira robs jewelry stores, deals contraband, and heads a gang of pickpockets. The hero of Vida nova por acaso [Odilon Lopez, 1970]) lives from picking pockets in Porto Alegre. The step in crime’s direction is even greater for the characters of Parceiros da aventura (José Medeiros, 1980): drug trafficking and a kidnapping with extortion - both poorly planned. In Pixote (1980), the drug-dealing Cristal corrupts youngsters, but enjoys his sports car, nice clothes, and impunity. All contribute to the ample social sketch in Cidade de Deus (Fernando Meirelles, 2003) where the Malandros, now bandits armed-to-the-teeth, fight among themselves rather than with the police.

Favelado

Of more recent origin, the Favelado [the unhabitant of a shanty town or favela, not always of Black origin] was soon codified as an archetype. The oldest description of a favela and its inhabitants is a chronicle by João do Rio, published in 1908 in the newspaper Gazeta de Notícias. There, the principal qualities and defects of this character are outlined: honest and hard-working; a samba aficionado; humble and intimidated when facing violence, authorities, etc. Almost a century later, the Favelado retains the same characteristics.

It was through him that the first “real” Blacks were presented in Brazilian cinema along with the truest portraits of the working class and jobless. Favela dos meus amores (Humberto Mauro, 1935), in which a (white) composer dies of tuberculosis at carnival’s end, enjoyed great success. The film was an important step in pioneering location shooting in the oldest ghetto in Rio [de Janeiro]. In a 1976 interview, the director declared “I captured life as it is.” A mix of precocious Neo-Realism (the semi-documentary scenes) and social ingenuity, this film combined two aesthetic and politically antagonistic tendencies (this, despite efforts to censor certain scenes). Unfortunately, no print exists.

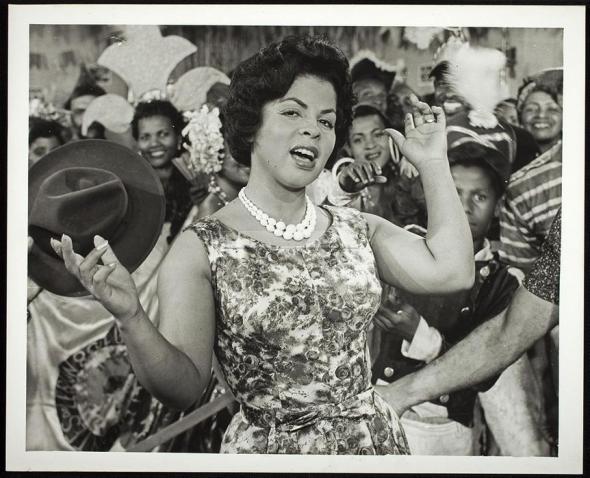

Orfeu Negro (1959)

Orfeu Negro (1959)

The paternalistic and ingenuous vision reached its height in Black Orpheus (1959), a French film by Marcel Camus, which won an Oscar and the Golden Palm of Cannes, breaking box office records wherever it was screened. Lightly inspired by the play Orfeu da Conceição (Vinicius de Moraes and Antonio Carlos Jobim, 1956), the Favelados suffer romantic setbacks, but social problems are sublimated to the most absolute, unreal happiness and the luxurious landscape of Rio de Janeiro.

Along a realist line, there are wonderful examples of favela life in two films by Nelson Pereira dos Santos: Rio 40º (1956) and Rio Zona Norte (1957). The first - its release at one point prohibited - shows the daily life of a group of (Black) children trying hard to make a living selling peanuts and the particular drama of each one. The second deals with a (Black) composer who dies after a fall from a train at the moment that one of his songs becomes a hit. Assalto ao trem pagador (Roberto Farias, 1962), another excellent film, shows a cross-section of ghetto dwellers in the most utter marginality and revolt.

1990s films reveal a much more complex ghetto: overpopulated, marginalized by the housing crisis. Its narrow alleyways are the stage for power struggles between drug traffickers and the state; Pentecostal churches and Afro-Brazilian religions; traditional (samba) culture and globalized working class (hip-hop) culture. It is an unjust and monstrous cultural caldron whose price is bloodshed, vigilante justice, and other extreme and non-democratic responses. In this chaotic environment, inhabitants have few options. Consequently, in Orfeu (Carlos Diegues, 1999), the love between Black Orpheus and mixed-race Eurydice has little chance to flower. The documentaries Notícias de uma guerra particular (João Moreira Salles and Kátia Lund, 1999) and Falcão, garotos do tráfico (MV Bill and Celso Athayde, 2006) confirm that reality is harsher than fiction.

Crioulo doido [Crazy Creole or Steppenfetchit].

In Commedia dell’Arte, the amusing Harlequin created misunderstandings and confusion. He is a cousin to the court jester who could, with humor and impunity, tell royals those truths forbidden other subjects. In the circus ring, he became the “colorful”, red-nosed clown with oversized shoes (in contrast to the white-faced aristocratic mime with cone hat, based on the Pierrot figure). In vaudeville, these histrionic functions were transferred to servants. That the archetype would be applied to Blacks in Brazil was not a big leap.

In Candomblé and Umbanda, the tradition of the Erês, infantile and mischievous spirits celebrated on the feast of Saints Cosme and Damião (September 27) already existed. Brazilian folklore also registers the Saci, a youthful, pipe-smoking, one-legged Black dwarf who is master of hiding objects and other pranks, theme for the film O saci (1953), inspired by the books of Monteiro Lobato.

In Brazilian literature, the archetypes associated with these African and European influences are the Crioulo Doido and his feminine equivalent, the Nêga Maluca [Crazy Black Woman], once frequent during carnival. The expression Crioulo Doido dates from 1966 when humorist Sérgio Porto based a samba parody, satirizing carnival regulations (which mandated patriotic themes), on a Black composer who muddles the whole of Brazilian history in an effort to meet these requirements. The song was a huge hit, but the archetype was nothing new, having a long-lived presence in Brazilian literature and playwright.

Brazilian cinema is full of this type who combines comedy, affection, ingenuity, and infantilism. Rarely a central character, he is generally side-kick to a white counterpoint, e.g., the comedic duos of Grande Otelo (Black), first with Oscarito, then Ankito (whites); and the role of Mussum (Black) in the comic strip Os Trapalhões, a children´s favorite. Even as an adult, the Crioulo Doido, almost always has infantilized characteristics, and thus is inoffensive in contrast to the dangerous Black Stud .

A much less innocent variation of Crioulo Doido is the abandoned minor, a street urchin, a budding delinquent. Seen in film since Moleque Tião (1943), he is better delineated in the peanut-sellers in Rio 40º and more dramatically drawn in the unfortunate Norival in Rio Zona Norte and in the distressing trio in the central roles of Pixote, culminating in the murderous children of Cidade de Deus.

Cidade de Deus (2002)

Cidade de Deus (2002)

Mulata boazuda [Sexy mulatta]

Companion and equal of Malandro, the iconic Mulata Boazuda variously combines the characteristics of the deities Oshun (beauty, vanity, sensuality), Yemaya (hubris, impetuousness), and Iansa (jealousy, promiscuity, irritability).

In Brazilian literature Manuel Antonio de Almeida immortalized the mulatta Vidinha in Memórias de um sargento de milícias and, in O cortiço, there is the seductress Rita Baiana. It was in vaudeville and burlesque, however, where the archetypal mulatta was definitively crystallized. In Maxixe (Bastos Tigre and Costa Junior, 1906), the ditty “Vem cá, mulata” became a resounding success. And finally, in 1922, light-skinned, almost white, singer Araci Cortes premiered on the stages of Tiradentes Plaza, as “the mulatta,” sexual symbol of the popular classes.

At a time when racial categories were much more rigorous, the novel A escrava Isaura (Bernardo Guimarães, 1875) dealt with a slave “who passes for white”. The melodramatic tone is very strong and the book was adapted twice for film (1929, 1949) and twice for television (1976, 2005) with great international success.

The character was always interpreted by white actresses. The same occurred with the mulattas in Gimbaand O cortiço (the heavily made-up Gracinda Freire and Betty Faria), with the domestic servant ofSamba in Brasília (1958) (the blonde Eliana Macedo), and with brunette Sonia Braga as Jorge Amado’s voluptuous Gabriela, in the 1975 soap opera and in the 1982 film. This was a change from the very beautiful “mixed-raced women with fine features,” popular sex symbols in the late 1950s, seen in. Black Orpheus and Barravento. Only in 1976, when Zezé Motta played Xica da Silva, did a Black woman with a typical black face appear in a sensual role, forever breaking this taboo.

The sexual appeal of the Sexy Mulatta is no small matter, as evidenced in pop music or the novels of Jorge Amado. With the sole purpose of exploiting this, a number of films were produced in the 1970s. It is sufficient to examine the titles and storylines: Como era boa a nossa empregada (an alluring domestic disturbs middle class familial tranquility); A mulata que queria pecar (the advertisement: “She knew that with that body she could conquer all men”); A gostosa da gafieira (an extroverted mulatta sleeps around, but loves no one); Histórias que nossas babás não contavam (a mulatta Snow-White in a comic-erotic treatment). Rather than “exalting” the alluring mulatta, these films actually exalt her white counterpart while she is reduced to an object of sexual consumption.

More complex are Adelaide in Rio Zona Norte, Maria in A grande feira, and Mira in Orfeu or Aurélia inGarotas do ABC. The first two are single mothers without many options. The second is an aggressive, knife-welding woman who places her daughter in a convent school and even makes plans for the future. The third, member of a large Samba school, poses nude for a male magazine, but, seeing herself displaced by a lighter woman, kills her lover rather than lose him to another. The last rejects Black men and is instead variously involved with a neo-Nazi and a Japanese worker.

Samba em Brasília (1958)

Samba em Brasília (1958)

Black Muse

The Black Muse, a still infrequent type in Brazilian media although elaborated since the nineteenth century, does not resort to vulgar eroticism. She is, rather, modest and respectable, a rarity in Afro-Brazilian media, where, even according to Black writer Lima Barreto “every level of society, without exception, believes that the natural destiny [of Black women] is prostitution or concubinage” (Gonzaga de Sá 1919).

The sketchy outline of this archetype is based on the authority of writers and poets of color: principally the militant poet Luiz Gama (1830-1882) or the Symbolic poet Cruz e Souza (1861-1898). In the novel Clara dos Anjos (Lima Barreto, 1921), the title character as much as her mother dona Engrácia are less idealized representatives of the Black family woman, practically absent in Brazilian cinema. Principal examples include the shy Euridyce of Black Orpheus (1958); the samba players’s wives in Natal da Portela (Paulo Cézar Saraceni, 1988); and the matriarchs in As filhas do vento (Joel Zito Araujo, 2004). The growing number of Black filmmakers and screenwriters favor this character over the more pejorative stereotypes.

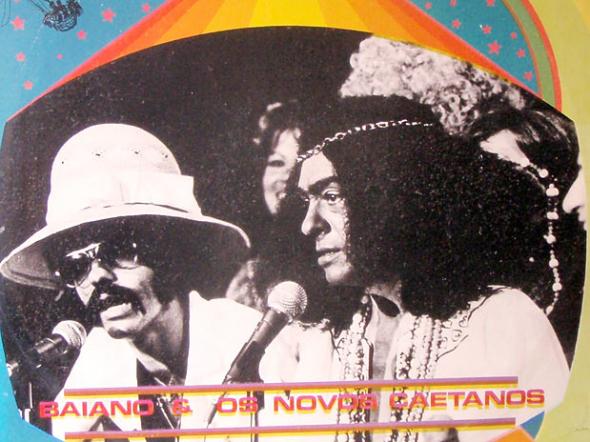

Chico City (cca. 1973)

Chico City (cca. 1973)