Contemporary dance from Africa as creative opposition to stereotypical images of Africanity

“There isn’t anyone, even in Africa, who can define for another person what Africa is.”

Boyzie Cekwana, South African Choreographer

This article1 is part of a long term research project on representations of identities and corporalities in contemporary dance from Africa. These processes are understood as complex and interlinked artistic strategies within local and international networks. On the one hand I try to understand how African dance and as African considered corporealities are used as an aesthetic medium in common European cultural practices: How does European discourse2 as well as the content. What is unsaid and unutterable is also to be analyzed. create which images of African dance and performances? On the other hand and crucially, I focus on the African side of the coin: a) how do African dancers and choreographers (re)act and which are their individual choices in the scope of various challenges and b) do European discourse have any significance on African dancers’ and choreographers’ decisions?

The study is based on the assumption, that dance permits both conclusions on habitual structures of the dancers and the aesthetic conditions of the cultural area. It focuses on the examination of individual agency and the developed strategies of appropriation and construction of post-modern identities within in this specific field of art. Beside the examination of relevant literature and archive material, it is based on qualitative research methods like interviews and participant observation. By the application of accompanying interpretative methods a description of the historical processes and the actual processes of creative response to this legacy should be possible by analyzing some of the works in detail with methods of performance analysis. In the article at hand, some first results and analyses should be presented.

The body as product, producer and medium of culture

By asking, if it is possible to challenge these stereotypical images, a closer look on the role of the body in society and the way how bodies are used to manifest specific worldviews is needed. Pierre Bourdieu’s theories are meaningful here to describe how bodies are part of the construction of everyday life and the conception of me and the other. According to Bourdieu, the body as medium of dance is culturally and socially shaped. Human experiences are inscribed into and onto bodies and thus, they will be perceivable through it and its expressions.

The body as medium of expression can be analyzed according to Odenthal as threefold: 1) as physical body, which already carries specific characteristics, which are culturally shaped, 2) as socialized body, inscribed with specific forms of behavior, which are partly understood as natural, 3) and finally as symbol for open communication, which is able to transgress borders into a “third space”. Johannes Birringer extends this argument by understanding the body as hybrid medial construct, which is confronted on one hand with repression and exclusion at the edges of society, and with desiring and imitation on the other. According to Judith Butler, the body must be destroyed and transformed to develop culture at all. People mark the outlines of the body similarly as borders of countries are pulled, and they try to establish codes of cultural coherency through that behavior. Possibilities to document and analyze the constitutions of new drafts of corporeality and artistic statements towards social processes are given in the study of dance. The consideration of dance in the field of art is of importance, since through physical action the staging of the idea of the own individuality and a mutual confirmation of cultural codes can succeed.

Dance as art, that works with the body as medium of expression, is thus to be investigated from two perspectives. First, we can analyse artistic utterances of sociopolitical processes, and second, we can examine how the body as medium of expression is understood and exploited. Oguibe emphasizes how such bodies lose self-possession and that they are forced to repeat a narrative of savagery and confess self-denigration and self-otherisation. In the words of Angela Dworkin they are turned into silent colonies, fragmented and projected for pleasure, parcelled and packaged to suit the Western tastes, to satisfy desires and fit in the frames of reference. Artworks and the discourses which are set up around are those places where corporeality is negotiated, interpreted and communicated. In the analysis of the distribution of power in the field of dance, we have to examine, who interprets which bodies in which way.

Thus, one focus is on the analysis of the everyday-cultural practices of Europeans in relation to African dance and as “African” perceived corporeality3. What is noticed as “African” in Europe is always already “staged”: the European gaze sees a modern Africa, which comes into being in areas of conflict and processes of adjustment in hegemonic post-colonial situations. While traditional dance was never a presentation in sense performing in front ofthe public, but took place including all participants, we cannot watch out for such “genuine traditional African dance” any longer today. The second line of interest is the examination of the possible influence of a discourse over contemporary African dance in Europe on African dancers and choreographers concerning their ways of performing and creating. These processes can be interpreted as struggles over identity4 and as coping strategies, taking the field of contemporary dance from Africa as one example for the challenges for artists and producers in the interlinked international art worlds of present day. Images and stereotypes5 of African corporeality also play an important role in European identity constructions. Historical events like the Hagenbeck’sche Völkerschauen at the end of the 19th century, the 1920’s Paris’ cultural scenery “black superstars” like Josephine Baker or the public appearance of National Ballets from African countries in the 1960’s are part of a process, where European identity and corporeality was constructed within an alleged opposition.

Josephine Baker, Tanzt Charleston

Josephine Baker, Tanzt Charleston

A history of African Corporeality

According to Stuart Hall, characteristics, that are perceived as “African” are reflected from the European perspective in order to enrich the own European identity.

By completing we avail forms of foreign cultures, which are taken for different reasons as adequate expression of personal arrangements. The images of the “different”, the “stranger” are linked syncretically according to a more or less conscious selection of the personal identity. Inadequacies and European mass-culture, which is perceived as boring, are compensated likewise by incorporation of foreign-cultural attributes. This superimposing of images can gradually lead to a permanent shift and reconstruction of terms like “European” or “African” corporeality and modes of behavior. Cultural elements, which were previously perceived as “new” and “strange” are integrated as “normal” and “European”, thus as part of the own.

Above all, the public viewings of “savage tribes” at the world fairs shaped the images of the savage and uncivilized Africans at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, and they served as confirmation of the prevailing evolutionist theories at this time. African dance was first received as Afro-American revue performances like Josephine Baker’s shows in Paris or Berlin, for instance. A further investigation would be needed for the representations of African National Ballets, which showed African dance on European stages as a form of emancipatory self-manifestation, but which also confirmed European ways of perceiving. The represented dances correspond to the pre-shaped images of “authentic Africanity”, instead of making it possible to offer other perspectives. African and Afro-American dance and bodies were noticed as distinct and were communicated with special attributes. This aspect was confirmed by the African artists themselves, which saw a possibility to emancipate themselves with their own culture. Events as the Premier congrès international de la race noire led by W.E.B. du Bois in 1919 in Paris and likewise the beginning of the “Negritude” movement in France and francophone Africa were a sign of a new afrocentric consciousness.

African corporeality in Europe is to some amount still perceived in frames of stereotypical images on the basis of this historical background drawn out here. This can be found in diverse reviews of cultural events with African participation. The authors seem to write out of their stereotypic frames of conceptions, how African bodies should be and what African dance only can be, what the following two examples show.

„The presence of the bodies of three men with naked chests is transmitting such an emotional force that is even too much for some of the spectators. But most of them are attracted by this form of art, that deserves to be called „passionate“.

„For unsociable middle-Europeans, the theatrical gestures seem strange, but they originate in their [the dancers] culture, are genuine and even not theatrical. Since content and move¬ment qualities are authentic, and Salia and Seydou are dancing their own concern and that of their continent, they can attain their audience“.

Contemporary African dance as post-colonial communication

The questions outlined above should lead to a critical investigation of the interlinked processes within the field of contemporary dance from Africa. We find many positions of artists here that can be analysed as strategies to cope with demands of Africanity and African corporeality in particular. To introduce in to this specific field of research, it is important to understand the recent developments of artworlds both in Africa and the European diaspora.

The continent Africa is merged into processes of (in the words of Appadurai) global cultural flows and African artists are not longer located not only in Africa and the African diaspora, but as well in the virtual, inter-medial areas, as for instance in video art or the Internet. Such places can be defined as “contact zones” between open cultural systems, and can as such be located in post-colonial discourses. Nevertheless, this post-modern Africa is still often noticed as “traditional”, and so in most cases with a claim for “authenticity”. This can be found for example in expectations from and in the reactions on African stage productions. In reviews of contemporary African pieces of dance the “authenticity” of African dance language and the special movement qualities are stresses, or the “emotional force” of a man dancing with naked torso is highlighted what we saw in the mentioned quote.

Johannes Odenthal, the former director of the House of World Cultures in Berlin argues that performing arts are a locality of postcolonial communication. Since about 15 years, African productions of contemporary dance are presented on international festivals. Effects of cultural-politics can be observed here, for instance the selection of a special kind of pieces, which are shown in Europe. Contents and choreographies of the pieces permit conclusions about the placement of the artists within the global cultural space. Cultural exchange between participants can be understood as one of the most important strategy of the actors to locate them in this specific art world. One of the questions to be analyzed is the possibility of different strategies in Europe and the African countries. Which options are at the disposal, and how are they used? Are there different ways of reception of the public both in Africa and Europe? Does this reception have any influence on the selection of themes? How is the contact between dancers and public both in Europe and the country of origin?

In the scope of African dance in relation to Europe, these procedures are not examined in detail. There are individual investigations about African dance in the diaspora, which refer to reduced regional areas as for instance Berlin or Frankfurt in Germany. A deeper research of the reciprocal effects, which take place between the participants and the recipients, is still pending. The conferences Movement (R)evolution Dialogues: Contemporary Performance In and Of Africa (University of Florida 2004), A new generation of African Dance (Berlin 2005) and Zeitgenössischer Tanz in Afrika – kreativer Widerstand zwischen internationalen und lokalen Kontexten (Düsseldorf 2008) pointed out that the discussions are still at the beginning. Many terms are still unsettled: The question about the placement of African dance as dance style with a long tradition on one hand and in the context of global productions of contemporary art on the other. The reception of African dance shows that clarification is urgent, because in the discourse, terms are used which indicate that the view on African dancers is often limitated and determined by ideas of “tradition”, “archaic”, “authenticity”, “wildness”, he or she is designated as an Other.

For example lusophone Africa offers a wide range of possibilities for investigation, since the dance-world has been opened in the last years for the contemporary dance similarly as in francophone Africa. Cultural contacts with the former colonies are maintained and supported in projects financed by different public and private sponsors (Instituto Camões, Fundaçao Gulbenkian, Goethe-Institutes etc.). Many dancers and choreographers reside both in their country of origin and in Portugal or other European countries. Projects such as Dançar o que é nosso / Alkantara were created as institutions of contact and exchange between lusophone countries. Meetings between dancers from Angola, Brazil, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Sao Tomé and Principe and Portugal took place since 1998. The objectives of such institutions reach from long-term cultural exchange and continuous mutual professional support to the development of a structural basis for an African artist community which understands itself as contemporarily African in an international context.

In 1995 the biannual Rencontres chorégraphique de l’Afrique et l’océan Indien (today Danse l’Afrique Danse!) was implemented in Luanda, Angola. It was organized by the French organ¬ization AFAA (Association française d’action artistique). This festival is decisively involved in the decision, which African companies are chosen to make a worldwide tour, and thus occur in the field of interest of the European dance-world. This year the festival took place in Paris and among the winners was the Mozambican group Culturarte. Likewise the first Angolan Trienal of Contemporary Art took place in 2006 in Luanda, where beside other art, dance and theatre played an important role.

The question of “Authenticity”

Dancers as well as the audience refer to some kind of “tradition”, which was earlier used as act of emancipation from (post)colonial restrictions in the time of the independencies of the African nation states. But this action may also serve to consolidate the heteronomy through an overlay with stereotypes. The cultural memory, to which the artists appoint themselves, and which is remembered anew within these processes, works thus at the same time traumatizing.

It is rather the concept of hybridization, which seems to be providing appropriate answers for intercultural processes. Neither essentialist evocations of a pan-african identity, nor the complete negation of any cultural affiliation and the dissolution of the individual into a global homogenized area can describe the actual processes of identity constructions suitably. Instead it is the blend of so-called traditional and post-modern elements which is of particular interest, since it shows up here that cultural processes do not proceed linear, but “as concatenation of temporally heterogeneous developments” in the words of Johannes Birringer. These ways of organizing art in intermediate cultures can be regarded as creative organisation of individuals, which are also subdued to hegemonic situations. It is necessary to find out, how this interrelations between liberty and obligation functions, and how the participants create alternatives to emancipate themselves in these relations of dependency on financial support and recognition in the art-worlds.

While post-modern discourses in art try to deconstruct essentialist determinations of identity, as for instance nationality or ethnicity, these are instead stated by people as a (re)constructions of the own identity. These movements in opposite directions can be documented also in the context of African contemporary dance. The dancers are confronted with a demand for the creation of something like Africanity in their performances. If this Africanity is missing, the dance is perceived as too European, and their legal status as “African dancer” is endangered. Otherwise, if their dance includes too much of what is coded as traditionally African, the dancers are judged as premodern or backwoods. This problem is one main topic in the ongoing discussions between dancers from Africa and Europe concerning the terms of authenticity and contemporaneity:

“By going to Africa to teach established dance styles and formats […] the teachers from abroad unwillingly created and often still create a dilemma for African dancers: either they have to assimilate the examples completely, running the risk of losing contact with their roots and with their local audience, or they have to invest a fusion of these extremely different styles with their own traditional dance forms and risk being seen as only second best in the occidental dance world they so much want to make contact with.”

Contemporary African dance as a field of friction represents a concrete example, which serves for explorations of art in general and corporeality as medium in particular. Directly or indirectly dancers and choreographers are demanded to take a stand concerning their own identity as Africans and their relation to (imagined) traditions, either on international stages or in African dance workshops. This differs from the discourse of classical ballet and contempor¬ary European dance, whose legitimacy is granted unquestioned. Contemporary African dance seems to work hard for this legitimacy.

“Unlike contemporary dance in Europe, debate about contemporary dance in Africa is poor and static.“

Ayoko Mensah stresses how important it is today for African artists to free themselves from the dependency of a conceived Africanity and to set their often intercultural shaped bio¬graphy as starting point for their own work.

“A new generation refuses the corset of a rigid and fictitious “Africanity”. As children of globalization these artists in same measure feel as citizens of the world and African, and they accordingly claim on universality“.

Moving centers - south-south and south-north networks

Since the 1990’s several networks began to work in order to elaborate mutual exchange of knowledge and means between artists in Africa and the African diaspora. This exchange is not limited to borders of language communities, even if we find closer connections in between francophone, anglophone and lusophone countries. But the last five years saw an increasing dialogue between self-organized institutions in African countries and their satellites in the European diaspora. This process can be read as the shifting of former centres, which accommodated for instance the power and legitimacy over definitions of quality.

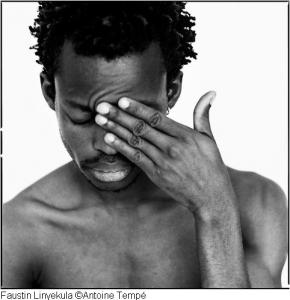

Some examples of newly inaugurated institutions which force south-south collaborations are for instance the Centre of Choreographic Development (Centre de development chorégraphique) - La Termitiere in Ouagadougou, which was opened by Seydou Boro and Salia Sanou in 2004 and organises every year the festival Dialogues de corps: This festival is designed as cultural and artistic event combining residences on choreographic writings, workshops, exhibitions, film shows and international meetings on the topic of dance programming. Germaine Acogny founded the organization Kaay Fecc and the associated school Ecole de Sables near Dakar in Senegal and Faustin Linyekula is the main organiser of the Studios Kabako in Kinshasa, Congo. These are only a few organizations working on contemporary dance in Africa, which become known in Europe. If there are organizations with smaller radius on local levels is still to be investigated.

One example of intercultural organizations, which connect northern and southern participants, is the contemporary dance festival Alkantara, which was formerly known as Danças na cidade in Lisbon. They focus on stimulating exchange and collaboration in small scale designed projects. Professional symposia about contemporary dance in Africa were organised in collaboration with the African contemporary dance platform of Africalia, which is located in Brussels. On these symposia the main themes that were discussed have been the importance of development of infrastructures for contemporary dance within Africa and the improving of comprehension of contemporary dance from Africa in Europe. The organizers argue, that contemporary dance in Africa is growing rapidly, and that the countries have to adapt to the needs of infrastructures, working on the base of long-term collaborations. African contem¬porary artists are confronted with various problems also in their countries themselves as well as by crossing borders to work in other countries and show their choreographies in international context. Since there is a lack of structures and bad conditions for economic survival, they often have to bring themselves in dependent relationships with cultural operators and organisations for foreign financing. The lack of freedom of expression is also still a serious problem in many of the African states.

The developing networks seek for strategies to enable the artists to work under better conditions. Concrete aims are formulated on regularly network meetings, which include artists as well as cultural operators, scientists and journalists. By sharing information on several meetings and building up cooperations with foundations they take important steps to emancipate from hegemonic forces and take standpoints in the current discourses. Existing spaces and infrastructure should be adapted for the needs of contemporary dance and new structures that are suitable should be created. Cultural operators should be trained to develop and man¬age venues, and spaces should be transferred to constructive final uses.

Exchange in terms of share not of needs – Developing infrastructures for contemporary dance in Africa

The lack of means and the little investment of African states in the cultural sector is one main problem. The following objectives are formulated to construct better conditions for contemporary dance: Workspaces should be shared starting at the level of sub-regions. African politicians should be involved in the meetings in order to build up lobbies in various African states. Northern hemisphere countries’ support is seen more in the context of short-term collaborations like international festivals. Support in long term relationships should also be stressed, for instance with logistical equipment like the AFAA project or with sharing of knowledge and expertise. On the other hand the problem of imbalanced exchanges that persists through these donations is seen as problematic. That the initiation of infrastructures in African countries, where contemporary dance is something new and maybe unknown, can be read also as some sort of postcolonial unequal relationship, should be regarded consciously. Reflections on a rethinking of terms of communication and behaviour are also made, since an exchange in terms of share than in terms of needs is demanded.

“It is important to understand that people working on dance in these countries feel very isolated. They are very well aware that dance is moving on a global scale and not being able to take part in this evolution is creating a growing frustration.”

The aim of projects like Alkantara is to help to build up organizations and networks that can work by themselves without the ongoing financial input from Europe.

“[…] the development of a contemporary dance scene in Africa can only come from Africa, […] from the conscious effort by African dancers and choreographers to develop their own dances”.

Improving comprehension of contemporary dance from Africa in Europe

“I don’t want to be treated as an African artist, but as an artist.”

Participant of the 1st Encontro dancar o que é nosso, Lisbon 1998.

The main questions outlined in the network-meetings concerning comprehension of contemporary dance in Africa are similar to the questions raised in my thesis: How do European audiences and programmers perceive African performances? How can understanding and reception be improved and what are the circuits and networks for contemporary dance from Africa in Europe? How can fair and balanced relationships be created in a context of unbalanced from a political, economic and social point of view?

Contemporary dance from Africa is discussed here as a “label”, which has implications on the discourse in different directions. The label serves for justification for artistic choices of cultural operators towards funders and audience, and increases the visibility of contemporary African dance by staging. On the other hand, the necessity of defining how to talk about contemporary dance from Africa is stressed, and theoretical approaches in order to build categories of communication are demanded. For instance one important clarification should be made on the difference between social African dance and theatre dance. The audiences should be sensibilised to be more aware of the wide range of creations from African choreographers.

Even if the reflections of the dancers relate to the political reality in their home-countries, they cannot be analysed without concerning the position of the artists in Europe. Institutions like the biannual choreographic competition Danse, l’Afrique danse! have to be analysed for their influence in cultural policy. This competition, which took place 2006 in Paris after having been organised in different African cities before since 1995 is decisive of the decision, which companies get the possibility of touring in the Northern hemisphere.

The increased appearance of African contemporary dance on European stages is perceived and the uncommon performance can insecure the usual ways of reception and the presupposed patterns of seeing, what is shown in the following quotation:

“Dance from Africa performed by the Compagnie Salia ni Seydou is not the usual and expected. Dance from Africa in the 21st century is new. It fits not into categories of style and tradition, and the dancers and choreographers do not respect the borders of the traditional culture of dance. The two founders of the company, Salia Sanou and Seydou Boro do what is normal for European artists: the right to develop and change their culture, art and themselves”.

While the emancipatory actions of the dancers are well recognized, the author of this advertisement is not able to quit the stereotyped categories, when she is talking about European and African gestures and movements. She focuses on the corporeality of the dancers, instead of writing about the content of the piece.

„Without denying their heritage, the dancers do not highlight their African roots in choreography and body language: gestures, movements, costumes seem to be European. But the style of the company Salia ni Sanou is not comparable with anything at all, and Africa is always there. Beautiful bodies are moving on the stage, they tell personal stories with the subtle play of their muscles and unite with the music to harmony. Dance from Africa is not longer the stamping of naked feet on the ground.”

These difficulties to interpret contemporary dance from Africa without stereotyped preconceptions can be found in many articles and reviews. The authors seek for patterns of Africanity that would legitimize the described dance as African.

“[…] the dancers are moving with force and grace, impressing and poetic […] with secure placement on the floor, but they jump very little. Bodily contact is seldom, but the work of the arms is partly as differentiated as a ballerina’s.”

“Finally they all find together in one of those African traditions, where sound, rhythm and movement become one, they stamp with their feet and make sounds with their tongues […]”.

Most clearly we can find the misunderstanding of the independent works of the African artists in the following quote:

“The leader of the choreographic centre in Montpellier [Mathilde Monnier] had integrated amateur actors from Burkina Faso into her piece “Pour Antigone”. The choreographers Salia ni Seydou learned choreographic composition, improvisation in a European way and the creation of theatrical images within Monniers company. […] A process of learning without self-alienation. […] In space and in the sound of blood […] movements that never deny their black roots, but have explored the freedom to dance in a open, contemporary manifold form – that always carries meaning – three men are dancing their fears, their friendship, their suffer on dead. Martial, aggressive, vulnerable – but always with gratitude. […] We can feel the new pulse of Africa, its flaming force. Its secrets.“

In these words we can still find the expectations of the journalist for authentic tradition and the unwillingness to confess individual creativity. In the eyes of European audience, composition and the use of theatrical images can only exist in African pieces, because the artists learned that somewhere in Europe. In this perception, African dancers should always keep in mind where they come from, and it would be a great sin to get rid of African roots by using only a dance language which is regarded as European. It is interesting to ponder, if such demands are ever posted to European artists?

Approaches to transcorporality – strategies of repossession of the body

Is it possible to decolonise the European gaze on African bodies? Olu Oguibe describes the ongoing struggle of African artists for the possibility of personal utterance, which is still denied within the discourse in the field of arts. It is “a struggle against displacement by the numerous strategies of regulation and surveillance that characterise Western attitudes towards African art.”

Within in the field of African contemporary dance we find these voices of self-articulation, that are able to formulate the artists version, not the “master’s narrative”. By this, artists struggle for the repossession of their own bodies and the reinvestment with language and articulation. They free themselves from the veto of enunciation which is a form of disenfranchising action.

The discussions of the network-meetings outlined above also stress on the treatment of individual African artists. They should not longer be treated as representatives of an imaginary Africanity, but as artists, that develop a personal artistic world. These works should be contextualized with respect to multiple traditions, European as well as African influences and individual research. The artists themselves are demanded to recover possession of the debate about African dance, both traditional and contemporary. According to Mensah, a large part of the young generation of choreographers from Africa seeks to overcome felt inadequacies inherited from the cultural history of their continent by developing a personal gesture.

The question is here, if these new modes of expression are sufficient to confront and challenge the stereotyped images of the audience. Are they able to develop emancipation from and opposition to the dominance of cultural institutions in Europe? Which are the subversive strategies developed by the artists?

Reversing stereotypes

According to Hall there are different strategies to reverse stereotypes, which is only possible by gaining control over them. He introduces this as strategies of transcoding, which means to take an existing meaning and re-appropriate it with new meanings (e.g. Black is beautiful). Transcoding strategies are used to acquire power for instance in the anti-racist movements since the 1960s. A positive attitude towards difference and a struggle over representations was part of an aggressive affirmation of black cultural identity. This was expressed in a series of films that are known as “Blaxploitation”-series, where blacks entered cultural mainstream with a vengeance. Stereotypes of black corporeality were challenged here, but also replaced by new ones like the well-known figure of the “gangsta”, which is relevant in today’s music and youth culture. The reversion of stereotypes does not automatically mean, according to Hall, to overturn or subvert them. “Escaping the grip of one stereotypical extreme […] may simply mean being trapped in its stereotypical “other”.

Josephine Baker, Burlesque

Josephine Baker, Burlesque

A second strategy is the attempt to substitute a range of “positive” images for the “negative” imagery which continues to dominate popular representation, which is underpinned by an acceptance of difference. This strategy inverts binary oppositions and privileges the subordinated. One example are the advertising series of Benetton, where ethnic models are continuously used to celebrate hybridity. The problem of this strategy is that adding positive images not necessarily displace the negative. The binaries are challenged but they remain in place and are not undermined.

A third counter-strategy introduced by Hall is located within the representations itself, and tries to contest them from within. It focuses the forms of racial representation instead of introducing a new content. This strategy works with the shifting character of meaning and enters into the struggle over representation while accepting that meaning is never finally fixed. This strategy takes the body as principal site of representation and attempts to make the stereotypes work against themselves. “Instead of avoiding dangerous terrain opened up by the interweaving of “race”, gender and sexuality, it deliberately contests the dominant gendered and sexual definitions of racial difference by working on black sexuality”. This strategy is not refusing the displaced power and danger of “fetishism”, but attempts to use the desires and ambivalences, and lays bare the psychic and social relations of cultural representations.

One of the theoretical questions was the possibility of the performative excess of codes of the standard. Is it possible to cause a transformation which can change the view of Europeans to African dance durably, and dissolve stereotyped images, even if only to replace them by new ones? Can “Africanity” be regarded without degrading, restrictive stereotyped samples? The participant is, after Bourdieu, able to step into distance from a field-specific standard, and cause a change. The question is here, if the African dancer leaves the alleged authenticity which is expected by availing technical means as for instance new media or other aesthetic forms which are received as uncommon, and do not fulfil the expected stereotypes? Can African bodies, by confirming field-specific ways of acting again and again withdraw from this perception at all? How can subversive embodiments look like, which do not only represent irony but an actual resistance and generate innovation? Bourdieu assumes in his concept of habitus, that the social position of a person in a speech act is determined, but not the speech act in itself. That means, that the body can disconcert the cultural meaning of the said in that moment, as it expropriate the discursive means, with which itself was manufactured. This can be seen as a moment of resistance by appropriation of norms, which is pointed against historically sedimented effects.

'Although I live inside… my hair will always reach towards the sun…' Robyn Orlin, bailarina - Sophiatou Kossoko, 2004 photo @Fiszer

'Although I live inside… my hair will always reach towards the sun…' Robyn Orlin, bailarina - Sophiatou Kossoko, 2004 photo @Fiszer

'Although I live inside… my hair will always reach towards the sun…' Robyn Orlin, bailarina - Sophiatou Kossoko, 2004 photo @Fiszer

'Although I live inside… my hair will always reach towards the sun…' Robyn Orlin, bailarina - Sophiatou Kossoko, 2004 photo @Fiszer

Finally I would like to highlight two artists that seem to find a way to create an active opposition to the stereotyped images, which could be something like Halls third counter-strategy outlined above. In the last years the African artists take oppositional positions after having been asked for their African authenticity for years. With radical formulations they attack clichés of African vitality and natural joy of dance.

Faustin Linyekula, for instance, a Congolese artist who founded “Studio Kabako” in 2001, a centre for dance and visual theatre, in Kinshasa, is working continuously in different projects in Africa and Europe. This studio was created as place for exchange, research and creation in the field of contemporary dance in Africa. In the 1990’s he was co-founder of the first contemporary dance group in Kenya, the Company Gaara, which is just one example for the ongoing south-south networks. For Linyekula, being African is nothing more than a coincidence. As he once said at a conference on African contemporary dance, he is born in Kinshasa in the 1970’s, but that’s all, he is just a contemporary artist, nothing more. For him, working with the body is the own possibility to achieve real freedom behind the stereotypes, because only the body possesses power. He works on the possibility to take a position without always be¬ing perceived as the “vehicle of his continent”. He lives and works in Kinshasa again after several years of travelling, For example he asks in his work what it means to live in a country that changes its name all the time (Etat indépendant du Congo, Congo belge, Zaïre, République démocratique du Congo…) and defines its history according the new circumstances.

“J’avais une histoire à vous raconter. Mais j’ai oublié. Je suis désolé”.

Another example of such a form of resistance is the newest piece of Seydou Boro (Burkina Faso) “C’est a dire ». This piece is his most personal and radical work, where he uses his voice also. For him, this piece is a fragment of his life; he felt the urge to show up naked in a solo that endangers him. Boro places many stereotypic questions, which he addresses ironically to himself and the (European) recipients (“why do Africans always dance with naked torso?”). In asking these questions as an African, he transfers himself to the more powerful positions, which was refused to him before by exactly the same questions. He also reflects the role of African contemporary dance in the arena of dance and points out on the efforts he has to take everyday to translate language and dance as artist in an intercultural sphere.

The piece “Ya Biso” by Djodjo Kazadi and Papy Ebotani in 2005 is created just for the dance itself. The title means “for us”, and the choreography is understood in the same way: no explication, no justification, no pretext, no history, and no concept. No comeback to resources, no avant-garde. The two dancers created that piece only for recover the pleasure of dancing. This strategy can be understood as defence of the stereotyped expectations that dance from Africa always should carry meaning.

Also the south-african choreographer Robyn Orlin and the dancer Sophiatou Kossoko were playing with stereotypes and let them work against themselves from within. In their last collaboration “… although I live inside…. my hair will always reach towards the sun” in 2005, they used stereotyped images of “black femininity” and by commentating the actions all the time, they undermining the act of theatre itself. She looks like an oversized Tina Turner with blond wig, huge eyelashes, a golden swimsuit and high heels.

Bibliography

Arnold, Stefan, “Propaganda mit Menschen aus Übersee. Kolonialausstellungen in Deutschland”, 1896 bis 1940, in Debusmann, Robert; Riesz Janos (ed.): “Kolonialausstellungen – Begegnungen mit Afrika?” Frankfurt/M. 1995.

Bernstorff, Wiebke von; Plate, Uta, Fremd bleiben. “Interkulturelle Theaterarbeit am Beispiel der afrikanisch - deutschen Theatergruppe Rangi Moja”. Frankfurt 1997.

Birringer, Johanner, “Der transmediale Tanz”, in: Kruschkova, Krassimira; Lipp, Nele: Tanz anderswo: Intra- und interkulturell. Münster 2004, 23 – 56.

Bechhaus-Gerst, Maranne (ed.), Die (koloniale) Begegnung. “AfrikanerInnen in Deutschland.” 1880 – 1915. Deutsche in Afrika 1880 – 1918. Frankfurt 2003.

Bourdieu, Pierre, “Distinction. A social critique of the Judgement of Taste”. Cambridge 1984.

Bröskamp, Bernd, Körperliche Fremdheit. Zum Problem der interkulturellen Begegnung beim Sport. St. Augustin 1994.

Butler, Judith, “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity”. New York 1990.

Butler, Judith,” Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”“. New York & London 1993.

Castaldi, Francesca, Choreographies of African Identities: “Negritude, Dance, and the National Ballet of Senegal”. Univ. of Illinois 2006.

Debusmann, Robert; Riesz, Janos (ed.), Kolonialausstellungen – Begegnungen mit Afrika? Frankfurt/M. 1995.

Dietrich, K., “Of salvation and civilisation: The image of Indigenous South Africans in European Travel - Illustrations from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries.” Unpublished D. Litt et Phil thesis, University of South Africa 1993.

Deputter, Mark, “Crossroads on interculturalism.” Brüssel 2003

Deputter, Mark, “Prácticas der interculturalismo”. Lisboa 1999.

Fanon, Frantz, “Peau noire, masques blancs”. Paris 1952.

Hanna, Judith Lynne, “To Dance is Human. A Theory of Nonverbal Communication”. Chicago 1979.

Hall, Stuart, “Who needs Identity”, in Stuart Hall/Paul Dugay (eds.), Questions of Cultural Identity, London 1996.

Hall, Stuart, “Representation. Cultural Representations and Signifying Practises.” London 1997.

Hall, Stuart. “Kulturelle Identität und Globalisierung”. In: Hörning, Karl H.; Winter, Rainer: Widerspenstige Kulturen. Cultural Studies als Herausforderung. Frankfurt 1999.

hooks, bell, “Black Looks: race and representation”, New York 1992.

Jones, Edward A., “Voices of Negritude. The Expression of Black Experience in the Poetry of Senghor, Césaire & Damas.” Valley Forge 1971.

Keil, Klaus, Durch Schmerzen zum Licht. Gelungener Auftakt des World Dance Alliance Festival in Düsseldorf. Kölner Stadtanzeiger, 27.08.2002.

Klein, Gabriele, “Electronic vibration. Pop Kultur Theorie.” Hamburg 1999

Levinson, Stephen C., “Pragmatik.” Tübingen 1990.

Lindfors, Bernth (ed.), “Africans on stage.” Studies in Ethnological Show Business. Bloomington 1999.

Luger, Kurt, Rudi Renger (ed.), “Dialog der Kulturen. Die multikulturelle Gesellschaft und die Medien.” Wien-St. Johann 1994.

Luzina, Sandra, “Körper ohne Grenzen. Zum Abschluss des Festivals” „In Transit“ im Berliner Haus der Kulturen der Welt. In Der Tagesspiegel, 18.06.2005

Mensah, Ayoko, “Corps noirs, regards blancs: retour sur la danse africaine contemporaine”, in Africultures No. 62, 2005.

Mensah, Ayoko, “African contemporary dance: towards a new South-North relationship?”, in Africultures dossier numéro 54, 2004.

Mensah, Ayoko, “5èmes Rencontres chorégraphiques de l’Afrique et de l’océan Indien: Tana en crise”, in Africultures No. 54, 2004.

Niederveen-Pieterse, Jan, “White on black”. Yale 1992.

Odenthal, Johannes, “Politics of translation” Die verborgenen Themen im Kulturaustausch, in Kruschkova, Krassimira; Lipp, Nele: Tanz anderswo: Intra- und interkulturell. Münster 2004, 135-145.

Odenthal, Johannes, “Performing Arts als kulturelle Praxis postkolonialer Kommunikation”, in Tanz Kommunikation Text. Münster 2003, 107 – 124.

Oguibe, Olu, Art, “Identity, Boundaries”, in Reading the Contemporary. Oguibe, Olu; Enwezor, Okwui (ed.). London 1999.

Quasthof, Uta. “Soziales Vorurteil und Kommunikation – Eine sprachwissenschaftliche Analyse des Stereotyps”. Frankfurt 1973.

Pfennig, Ursula, “Rituale und Leidenschaft. Das Festival „global dance 2002“” bietet in Düsseldorf eine breite Palette von zeitgenössischem Tanz mit 50 Ensembles aus fünf Kontinenten. Westfälischer Anzeiger, 26.08.2002.

Royce, Anya Peterson, The Anthropology of Dance. Bloomington 1977.

Siegert, Nadine, „Afrikanischer Tanz in Deutschland“. Eine Studie zur Genese und aktuellen Situation afrikanischen Tanzes in Deutschland, unpubl. master thesis, Institute of Ethnology und African Studies Mainz. 2003.

Sieveking, Nadine, “Empowerment via embodiment. The Transcultural Practice of African Dance in Berlin - Die Bedeutung des Körpers in transkultureller Praxis am Beispiel der afrikanischen Tanzszene in Berlin”, in Sociologus, 2002 (2), 215-244.

Tarver, Stanley, African continuities in African American social dance, in Dagan, Esther (ed.) The Spirit’s Dance. Evolution, Transformation and Continuity in Sub-Sahara. Montreal 1997.

Walgrave, Jasper, Dançar o que é nosso, in Deputter, Mark: “Crossroads on interculturalism”. Brüssel 2003.

- 1. This article is based on a presentation at AEGIS Summer School; Cortona (Italy), 2006

- 2. I use the term „discourse“ to describe institutionalized speech in society, which influences actions of the members of the speech community. Form and function of speech acts are part of the analysis The project is not yet framed by an institutionalized support, thus being work in progress since its be¬ginning in 2004. Through ongoing discussions with both artists and other researchers related to that field, it received continuous updates. It is planned to be developed and focused in close collaboration with artists and producers in a case study on the contemporary dance scene in Nairobi (Kenya) in near future.

- 3. The first definition of Corporeality is “the quality of being physical; consisting of matter (syn. Corporality)”, but I prefer to argue according to Judith Butler that even the physicalness of our bodies is not an absolute certainty but is, however, invested with a “certain capacity to originate and compose,” which leads to intelligibility. Butler further proposes that matter is “clearly defined by a certain power of creation and rationality,” so that to know the “significance of something is to know how and why it matters, where ‘to matter’ means at once ‘to materialize’ and ‘to mean’”. If the body then is clearly matter, how that body comes to materialize, mean, or matter is contingent on its origination, its transformation, its potentiality. The body’s intelligibility therefore is not a given but is produced. Butler identifies the production of this intelligible body at the site of performativity or “specific modality of power as discourse (Butler 1993)”.

- 4. My perspective on the topic of identity derives from the ideas of a construction of identities affected by socialization, status, distinction, acquirement of acceptance within specific fields and education. The struggle to find and construct identities is dependent on positioning and placement in a specific society and their groups (see e.g. Luger 1999, Hall 1997, Hall 1996, Hall 1999).

- 5. For stereotype the following definition is useful: „Verbal (and nonverbal) utterances that are focused on social groups. They have the form of logic judgements, simplify in generalizing manner and adjudge certain characteristics“ (Quasthoff 1973).