The Party of the Dead

Portugal’s The Party of the Dead held performance art events on August 3, the anniversary of the death of António de Oliveira Salazar. This refers not to a metaphorical but a literal “fall” — an everyday injury, a head injury sustained by an elderly man, which led to the rapid decay and dismantling of the Estado Novo regime. According to one version, Salazar fell from a deck chair; according to another, he slipped in the bathroom. Supporters of the second version claim that the propaganda machine wanted to present to the press the image of a wise old man reading a newspaper in a deckchair and reflecting on the fate of the state, rather than a naked, wet old man who slipped on a puddle in the bathroom.

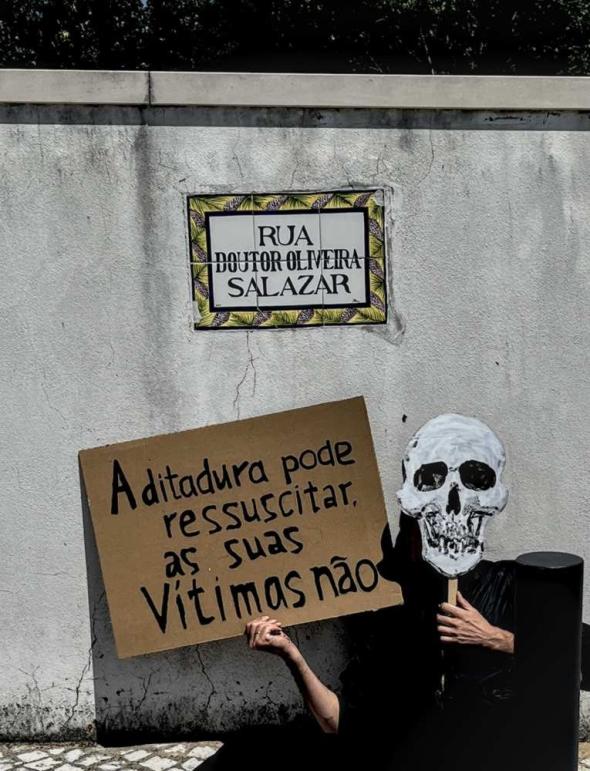

It is not known which version of the incident is true, but it is clear that totalitarian regimes rely on censorship and aestheticize heroes and metaphysical narratives. The Party of the Dead staged performances at the Santo António da Barra fort and on the street that still bears the name Doutor Oliveira Salazar. Strangely enough, 51 years after the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, more than 17 place names bear the name of Salazar, and more than 700 bear the names of figures from the Estado Novo regime. What should be done with such political memory? Should monuments be demolished and geographical names be renamed? The question is complex, but the current situation clearly requires reflection and commentary.

Ethical horizons are shifting: those who were once called pioneers and explorers are now seen as colonizers and slave traders; the “founding fathers” and noble knights are now seen as psychopaths who fought for power and money by any means necessary, without regard for the lives of others. History needs to be revised. This is a task that must be done in order not to lose our freedom and become accomplices to new crimes.

The art group The Party of the Dead was formed in Russia in 2017; its members have created numerous performances, working with the theme of the necropolitics of Putin’s regime and his party. In one interview, artist and group member Ivan Zagibly describes the situation in Russia as follows: “Dictatorship does not come instantly; it takes twenty years. First, the media comes under the complete control of the party, then the courts and the legislature; NGOs are shut down; new laws restricting rights are passed; independent internet resources are blocked; the number of political prisoners grows. Most people don’t notice this: the economy is growing, salaries are rising, everyone is getting used to it. It’s like alcoholism: at first, it becomes normal to drink every day, then for weeks at a time, then to live in short, gloomy intervals between binges. At each stage, it seems that everything is still under control, and excuses and normalization of the current stage of intoxication kick in.

After the collapse of the USSR, Russia went from wild capitalism and a “blackout” of power, when control passed to criminal groups, to a harsh authoritarian state where everything is controlled from the center through repression, censorship, and propaganda. Against this backdrop, Stalin was rehabilitated: speakers appeared in the media claiming that there were fewer victims of the Gulag, that repression only affected criminals, and that terror could be justified by economic growth and “stability.”

Such narratives are not only noticeable in Russia: in many countries, political forces manipulate the audience through resentment, turning their gaze to lost power and achievements, while remaining silent about their price. This raises the question: do the carnival actions of The Party of the Dead devalue political expression? The answer depends on the audience. In a museum or academic context, the statement may dissolve into symbolic capital, but for the general public, the artistic gesture works as a direct, albeit naive, speech or as a meme. Memes and tweets are often more effective today than manifestos and speeches from the podium.

The Party of the Dead itself has become a media outlet: thousands of people subscribe to its social media channels, and anyone can create a “meme” skull with a text plate and write their own statement in the party’s frame. It is interesting to compare its actions with the works of Artur Barrio, dedicated to the victims of dictatorship. In the series Situacão T/T, 1 Barrio lays out bloody bundles of meat and bones in the city, confronting passers-by with the physiological reality of torture in everyday life, rather than on the pages of newspapers. These bundles cannot be called memes: they provoke a street situation involving the police, firefighters, and random passersby.

The performance The Party of the Dead, timed to coincide with the fall of Salazar, does not create a street situation; its documentation goes to social media in the form of memes, reflecting the work of modern political parties. According to open sources, Donald Trump spent about $45 million on social media advertising as part of his 2024 campaign — an amount that is likely underestimated, as some of the purchases were made through third-party structures that promoted posts on criminal topics involving migrants or publications by far-right bloggers.

If politics moves online, what should we do with the hypothesis that the internet is the “realm of the dead”? First, the internet resembles an archive or a cemetery: a significant portion of its content was created by people who have already died or organizations that have closed down; a large share of traffic is generated by bots, crawlers, and AI. Thus, The Party of the Dead simulates “zombie politics” in the “realm of the dead.”

Sometimes the group’s actions look more like magical rituals than actionism. At the Santo António da Barra fort, for example, a message appeared: “Poutine julga que ainda governa URSS” — a reinterpretation of the headline of Salazar’s last interview, where a journalist from L’Aurore notes that the dictator lives in his own world and is convinced that he still rules the country. This seemingly meaningless gesture brings together coincidences of time, place, power flows, and madness in one point — a gesture of despair or a ritual performed according to unclear rules in the hope of provoking a new coincidence and overthrowing another dictator, physical or metaphorical.

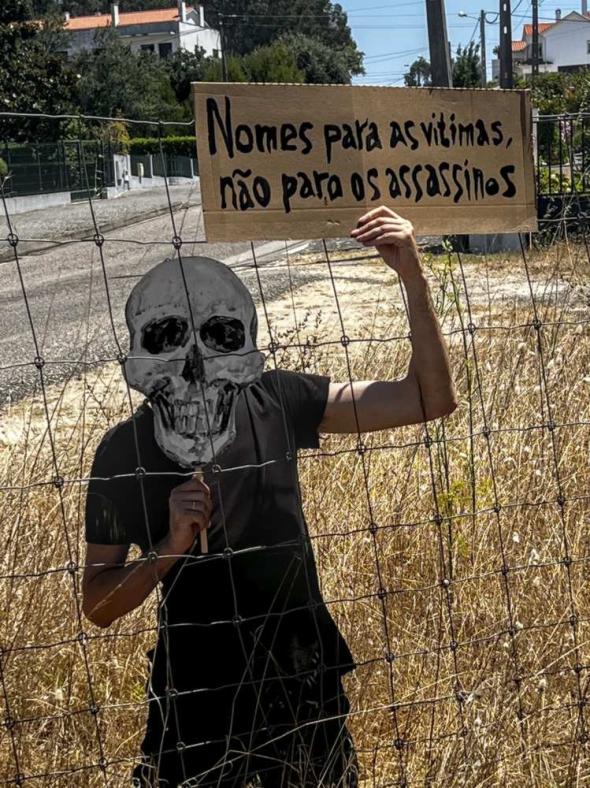

In addition to this inscription, other phrases were also seen on the plaques…

God, Motherland, Seed, Work, Death;

Dictatorship Can Be Resurrected, But Its Victims Cannot;

Names For Victims, Not Murderers;

The Dead Have No Leaders, And The Living Do Not Need Them;

Patriarchy Must Fall;

Dictatorship Has Taken A Break, But Is Ready To Return;

Dictatorship Comes Slowly, We May Not Notice How We Are Being Poisoned;

Enough Of Justifying Dictators Through Economic Success;

Imperial Ambitions Create Dead People;

Imperial Ambitions Create Dead People;

Every Dictator Has A Slippery Future;

More Dictatorships = More Dead People;

Ricardo de Kores