Tales of oblivion (or of our shameless lists)

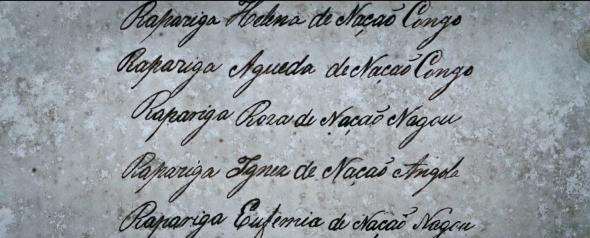

Young girl Marcella from the Angola nation, young girl Engrácia from the Angola nation, young girl Serafina from the Nagou nation, young girl Eufémia from the Benguela nation, young girl Esperança from the Angola nation, young girl Umbelina from the Angola nation, young girl Emília from the Benguela nation, young girl Suzanna from the Angola nation, young girl Libânia from the Nagou nation, young girl Cecília from the Angola nation, young girl Helena from the Congo nation, young girl Águeda from the Congo nation, young girl Rosa from the Nagou nation, young girl Ignez from the Angola nation, young girl Eufémia from the Nagou nation, young girl Balbina from the Angola nation, young girl Emília from the Nagou nation, young girl Eufrazia from the Benguela nation, young girl Jacinta from the Nagou nation, young boy Paulo from the Angola nation, young boy Marcos from the Congo nation, young boy Teodoro from the Nagou nation, young boy Tertuliano from the Casange nation, young boy João from the Angola nation, young boy Manoel from the Congo nation, young boy Julião from the Nagou nation, young boy Paulo from the Nagou nation, young boy Sebastião from the Congo nation, young boy Marciano from the Nagou nation, young boy Gil from the Congo nation, young boy Francisco António from the Angola nation, young boy Bernardo from the Nagou nation, young boy Pedro from the Congo nation, Joaquim from the Nagou nation, young boy Paulino from the Luanda nation, young boy Francisco from the Nagou nation.

These names are part of a list, whose same logic inspired another list composed of the names of several children from a Portuguese public school to be read by the Portuguese (neo) colonial-fascist party in Parliament, which exposed these same children to hatred and violence (in Portugal as in Palestine). The list I have partly copied above is a document, perhaps a list of those arriving in a slave ship, which the Portuguese filmmaker Dulce Fernandes included in her latest film, Tales of Oblivion (2023, 63’) — an archaeology that excavates Portugal’s role in the transatlantic slave trade and its legacies in the present. In other words: today’s list read at the Portuguese parliament is only possible because in the past there were lists such as the one I replicated here.

Assembling historical documents pertaining from various institutions (such as Lisbon’s Overseas Historical Archive and the National Archive of Rio de Janeiro) with images and sounds from the present – and thereby shattering the “imperial temporality” that separates time into past, present, and future – the film begins with the discovery, in 2009, of 158 human remains of children, women, and men in what was once an old medieval dump on the outskirts of the city of Lagos, in Southern Portugal. The human remains date from the 15th century and were identified as being of African origin. Some of the human remains show signs of trauma, such as fractures and shackled wrists, while others, quite the opposite, showing signs of care in their burial. Therefore, this isn’t just a dumping ground, but a cemetery: one of the oldest mass burial sites of enslaved Africans, as Vicky M. Oelze of the University of California-Santa Cruz points out. Unlike what happened in New York, where the African Burial Ground National Monument now stands and where the found human remains were returned to after being studied by Howard University, in Lagos, the human remains, which Dulce Fernandes so carefully evokes, without ever actually showing them, are imprisoned at Dryas, the private company responsible for their excavation in Lagos. The remains are echoed in the images of the labeled boxes that contain them, and in the images of Dryas’ sterile, cold facilities—unsuitable for mass burials.

This is not a “cerebral” or “abstract” film as some have labeled it, but rather one that offers an exemplary approach if compared to other recent Portuguese documentaries, exhibitions, and books that, in their eagerness to understand the “visuality” of the Portuguese empire, fall into its vertigo. Instead, Tales of Oblivion tells a story of violence without resorting to violent images (even when it sets in motion the famous image of a slave ship, which, having been engendered for abolitionist purposes, does not subsume to that same equation). It does so by questioning the documentation protocols that “experts” often employ and, in doing so, are oblivious of the degree of destruction that the production of such documents entails, which, in turn, maintains “imperial rights” into force, as Ariella Aisha Azoulay (2019) pointed out. Such as, for example, the right to undermine the safety and dignity of children by listing their names in public, just because they are migrants or of migrant parents.

A list is like a photograph, but a non-photographic photograph. A mental image that produces, simply by cataloging its subjects, an effect that is both material and affective: a “camera lucida.” It produces a “visuality,” an aesthetic (who can forget the murderous lists of concentration camps?). This is the reason why the ignoble (neo) colonial-fascist MP can recite this list in the Portuguese Parliament: so that what is not seen, can be seen—his point of view. In the case of the list with which I begin this text with, Dulce Fernandes does not show us any other information that the list possibly contains, judging by other similar lists that rest in the colonial archives. Even so, this list is violent per se: not only because the spectator deduces that these were not really the names of those young girls and boys (and part of the colonial violence consisted in erasing people’s original names and thus their culture of origin), but also because, for this list to exist, an “imperial agent” had to arrest their bodies, gaze at them, describe them, and record them. Ariella Aisha Azoulay designated this modus operandi as the initial moment of photography, dating it to 1492, when “worlds were destroyed.” When it was invented as a technique in the 1830s, photography was just documenting a “world that was already there”: one of division, plunder, and “imperial rights.”

But perhaps we need to go back a bit further, to 1444, when the Portuguese Gomes Eanes de Zurara (1410-1474) described, in an ambivalently vivid manner, in chapters XXIV, XXV, and XXVI of his Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea (1451), the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Lagos (and thus Europe) —the “photographic” event that precedes what the landfill/cemetery bears witness to today. Lagos – just as in Lisbon, through the initiative of DJASS-Afro-descendent Association and the vote of Lisbon’s residents in 2017 – still awaits for the memorialization of this inaugural event of Modernity (which decolonial scholars have coupled with Coloniality – in which one concept cannot be understood without the other). Lagos municipality has plans for a memorial next to the burial site, but it is laughable to imagine how it can coexist with a mini-golf course. With 92 golf courses in Portugal, half of which are in the Algarve, does Lagos really need another one? A poignant metaphor for a model of development (and non-memorialization) that the Portuguese political elites have reproduced ad nauseam, and which was modelled, in turn, by the plantation regime, inaugurated precisely by the Portuguese in 15th century Madeira Island.

Tales of Oblivion’s final shot is an overview of the erasure produced by the parking lot and the mini golf course, while one of its opening shots shows us a huge contemporary landfill, before turning our attention to the eucalyptus grove next to it. Between one shot and the next—and, once again, to escape the violence of representation—Dulce Fernandes resorts to elemental materiality: the mass of water that is the vast and turbulent Atlantic, the whistling wind that moves the treetops, the earth or seeds that a backhoe gathers in the hold of a cargo ship. In the meantime, the filmmaker also places the spectator on a ferry boat (which stands in for a slave ship), makes her feel the labyrinth of the Lagos car park (a metonymy of Portuguese colonial memory, as the Portuguese philosopher Eduardo Lourenço noted in 1999) and even fulfills Portuguese writer José Saramago’s wish, rehearsing the necessary museology for “the proof of a major crime” – the 18th century collar of a man enslaved by the Lafetá family, which “is worth as much as the Jerónimos Monastery, the Tower of Belém, the [Portuguese] President’s palace and the carriages, wholesale and retail, perhaps even the entire city of Lisbon” (1981).

Tales of Oblivion is like a spider web that Dulce Fernandes iconoclastically constructs by promoting an unlearning of the “documentation protocols” and by intuiting that “not everything can be seen by everyone”. She films her object as an object in which “non-imperial rights” are inscribed, and which, with her careful gesture, the filmmaker restores (for her and for others). Tales of Oblivion is anchored in an image construction tradition (think of J.M.W. Turner and how the abolitionist painter evokes the crime of the slave ship Zong) that serves as a counterpoint to the cumulative effect of the list read by the colonial-fascist MP at the Portuguese Parliament and the torrent of “images” that his party incessantly produces, aiming at the colonization of the whole political imaginary (yesterday the children’s list, today the demolition events at Bairro do Talude, in the outskirts of Lisbon). To dismantle this effect, it is urgent that each one of us asks at every instant: am I filming—seeing, producing, gesturing—like the colonial-fascist MP or countering him?

Film screening & discussion: October 22, 7pm, KJCC Auditorium, New York University (53, Washington Sq. South)