Memory work as “radical intervention” and “reparation”: interview with Marita Sturken

On the occasion of the publication of her new book Terrorism in American Memory: Memorials, Museums, and Architecture in the Post-9/11 Era (New York University Press), I interviewed Marita Sturken, whose work focuses on U.S. politics of memory and visual culture. Full professor in the Department of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University, she is also an advisor to the Doctoral Program in Artistic Studies at Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, where she also taught.

Sturken’s insightful scholarly work transpires a true transdisciplinarity, in line with her Ph.D. in History of Consciousness at the University of California-Santa Cruz, where she studied under the supervision of the late historian Hayden White. It is also attuned to her earlier professional experience as a photographer and art critic.

Marita SturkenAmong many articles published in respected journals, she has been contributing to the fields of Memory Studies and Visual Culture with fundamental books, such as Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (1997) and Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero (2007), in which Sturken deals with a vast and expressive archive of memory practices and technologies. Her work demonstrates the complexity as well as the epistemological interest of how the objects, and therefore the analysis, of memory studies promote a dislocation of the temporal sequences and categories on which history as a discipline has established its deep foundations.

Marita SturkenAmong many articles published in respected journals, she has been contributing to the fields of Memory Studies and Visual Culture with fundamental books, such as Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (1997) and Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero (2007), in which Sturken deals with a vast and expressive archive of memory practices and technologies. Her work demonstrates the complexity as well as the epistemological interest of how the objects, and therefore the analysis, of memory studies promote a dislocation of the temporal sequences and categories on which history as a discipline has established its deep foundations.

She is one of the authors included in the groundbreaking The Visual Culture Reader (1998/2013) edited by Nicholas Mirzoeff, and, together with Lisa Cartwright, co-authored one of visual culture’s pedagogical classics, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture (2001) now on its third edition (2018), which teaches how to look at different media, while providing an overview of the field’s concepts, theories, and methodologies. Her versatility as a scholar is also demonstrated in the book Thelma & Louise (2000), a cultural and media analysis that unpacks gender, landscape and “gun culture” in the United States. One of the best takes on this iconic movie, it has now been republished (2020) in the wake of the 30th anniversary of its release and the #metoo movement.

From souvenirs to snapshots, quilts to memorials, icons to museums, and films to selfies, Sturken’s analysis shows how cultural memory is a negotiation over the meaning of the nation and unravels the ways in which memory is materially shaped and how it is contested. In so doing, she has been building a body of work politically sophisticated in its entanglements and of which her new book, Terrorism in American Memory: Memorials, Museums, and Architecture in the Post-9/11 Era, is the most striking example. Most importantly, Marita Sturken is one rare and generous scholar-pedagogue – one who knows how to lead into knowledge.

Check Marita Sturken’s website (including access to her many articles):

Although no longer an emergent field, memory studies is still fairly novel, having emerged from the “spectral turn” in the 1990s. Broadly speaking, memory studies examines the representations and materialities of the past, how they have lingered and/or are put into question in the present, how do the politics of memory and forgetting shape social policies, and how that impacts the nation or certain communities. Its institutionalization occurred in 2008 with the first issue of the Memory Studies journal, in which you participated in with an important article, “Memory, Consumerism, and Media: Reflections on the Emergence of the Field”, and then, in 2016, with the foundation of the Memory Studies Association, which has been organizing annual conferences since then. It is a broad field, and a lot of work has been vindicated under its umbrella.

Twenty years on, what are the most pressing questions being put forward by the field today? Can you also elaborate on the ethical and political stance that working with the materiality of memory often entails?

Your description of the codification of the field of memory studies is apt. I would argue that it is hard at this point to generalize about the field. A journal like Memory Studies aims to define the field across the humanities and social sciences through to psychology, so the range of work that might identify with memory studies is quite broad at this point. I see the field of memory studies in the humanities moving increasingly away from its origins in literary studies, trauma studies, and Holocaust studies toward visual culture, media studies, and debates about racial injustice.

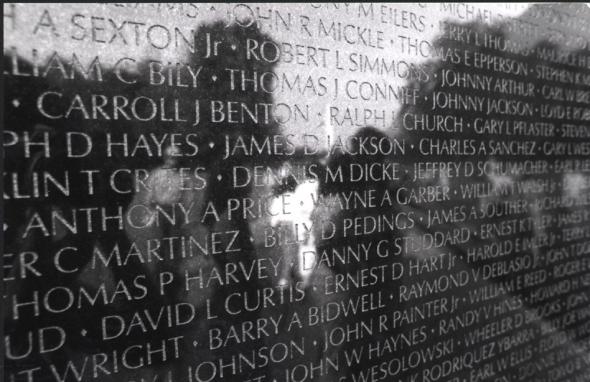

When I was first interested in cultural memory, as a graduate student in the late 1980s, it was not yet a field of study but a research topic. Yet, I was pulled by it because it had already emerged in public discourse in the United States as something important, a kind of structure of feeling, in what we would say now was the beginning of the “memory boom” in Europe, the US, and Latin America. In the US, the embrace of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial starting in 1982 set into motion both a new affective national language about memory and a rash of memorial building, and the AIDS Quilt made clear by the late 1980s, the power of memory as a form of activism. It was such a radical project, one that appropriated American folk art to mourn those who died of AIDS and also to proclaim, especially when it went to Washington, that they were Americans and that America had AIDS. So my dissertation began with those two memorials, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the AIDS Quilt, as radical interventions into memorialization that opened up an entirely new terrain for memorialization and for thinking about the fractured nation.

Today, I think that the field is challenged more than ever by the increased volatility of debates about what nations remember and consequentially forget. Monuments and memorials are being vandalized, torn down, officially removed. They can no longer be seen as simply part of an historical landscape. Much of this can be understood as battles over the historical narratives of monuments and their power, but it is also about tensions around who the nation mourns and who it sees or does not see as having a “grievable life” in Judith Butler’s term. So I see memory activism as a key site for the production of memory scholarship.

Memory Studies promised “to rework history’s boundaries” as Kerwin Klein put it in a foundational text (2000).Indeed, at its very foundation, the field includes a distinction between memory and history with the relationship between both being key. In opposition to Pierre Nora’s view of history as opposed or “suspicious” of memory, you have posited them as “entangled” rather than oppositional (2007), placing cultural memory as the basis of your intellectual enterprise, namely in Tangled Memories. The Vietnam War, the Aids Epidemic and the Politics of Remembering (1997) and Tourists of History. Memory, Kitsch and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero (2007). This dynamic of entanglement is essential to understand the interest of the mnemonic objects you examine, the way in which they not only invoke the epistemological interwovenness of different disciplinary approaches, but somehow are already a product, an embodiment and a manifestation of that same entanglement. Memory studies engage with the objects that resist time or what Hayden White called the “practical past” (2014). Therefore, one can say that memory studies, not being a discipline, brings a disciplinary problem to the world of disciplines.

In what ways has memory studies broadened the epistemological horizon of history and, consequently, historical knowledge and why do you think that is important?

French historian Pierre Nora was very influential in the formative years of memory studies (the publication of the introduction to his book Les Lieux de Mémoires in English in the journal Representations in 1989 is really an origin moment for the study of memory in the US). Nora saw memory and history as opposed, with history’s aim to destroy memory. Nora’s work is fundamentally about a mourning for a kind of organic, peasant memory that had been lost in France, and replaced by lieux de mémoires, modern forms of memory like monuments, statues, anniversary rituals, memorials, etc. Nora sees these an inauthentic to the organic, oral passing down of memory. But we have long moved past that kind of nostalgic paradigm.

In contrast, I think of memory and history not as in opposition but as effectively entangled, all messed up together. Nevertheless, I think there are moments when it’s important to make distinctions between memory and history, when the politics of each are quite distinct. For me, the distinction also has a lot to do with how these terms and categories are deployed politically. When we are talking about cultural memory we are always talking about a politics of memory, how it is being marshalled, deployed, reproduced, and enacted. Memory is actively a site where negotiation over national identity takes place, precisely because it is a site where the past is experienced within the present.

One of the ways I have thought about this relationship of memory to history has been to think of the “traffic” between personal/individual memory, cultural memory, and history. So, as you note, I have consciously in each of my works looked at cultural objects across social/cultural arenas, from official memorials, museum artifacts, films, architecture, and photographs to snow globes, cheap souvenirs, and kitsch objects. And one of the most intriguing aspects of these varied objects is how they can migrate across these categories. This was one of the first insights I had in looking at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in the late 1980s, that the objects that were left by veterans, family members, and others at the memorial (something no one had done with any other memorial in Washington, D.C.) had been personal objects of memory that were then shared in the realm of cultural memory when placed in a public space such as the memorial. But the National Park Service began to collect them, first in a lost and found and then in an archive. At this moment those objects were transformed into historical artifacts, which could only be held by gloved hands. So they moved from personal objects to objects of cultural memory to historical objects. Yet, at the same time, they are very cryptic objects, some might have explanatory notes left, such as a note from a veteran that describes how he took a photograph of a Vietnamese man and his daughter from the body of a man he killed, and carried it in his wallet for many years before leaving it at the memorial. But many are messages only for the dead, hard to decipher – a bottle of whiskey, even a motorcycle. I was really interested in the cryptic nature of these objects, as publicly shared yet constituting private conversations with the dead.

I was also interested in the traffic that moves in the opposite direction, from history to cultural memory to individual memory, which happens often with photographs. There are so many instances when people as individuals “remember” experiences that they themselves did not actually experience. Often this happens through popular culture and photographs. So we might remember “witnessing” an event that we did not – many psychological studies on flashbulb memories (memories in which you remember where you were when an important historical event happened) show that people often misremember where they were and rewrite themselves into a collective script, remembering seeing 9/11 in person when they saw it later on television, etc. Many Vietnam veterans, for instance, talk about how their memories got entangled with the images of Hollywood movies about Vietnam and documentary images, to the point where they could not separate what was their own memory.

While my work has focused a lot of memory, I always feel that the real topic I am constantly aiming to make sense of is the nation, specifically the United States, a complex and destructive entity of competing values and discourses. I am always asking, how is memory being deployed as a means to shape national narratives? In my book Tourists of History, I argue that US national culture has a “tourist” relationship to the histories of violence it has perpetrated, always outside looking in without being implicated. I argue that this is enabled by a kitsch culture of sentimentality, memory souvenirs, popular culture narratives of American innocence, and comfort objects like FDNY teddy bears. A teddy bear sold at a gift shop at a memorial museum like the 9/11 museum embodies this kind of tourism of history, providing comfort narratives about the ways things are.

The turn toward memory over the last few decades has not only been about a reckoning with the violent histories of the 20th and 21st centuries, but has also been an opening for a less rigid sense of history, for a recognition that history is fluid, needs constant revision and rethinking, and negotiation. In our contemporary moment in the US, the battles over the meanings of national history are particularly intense, and it is crucial for us to be attentive to how historical narratives are deployed in the present (today, often in retrograde and brutal ways) and the importance of challenging historical narratives to see what they leave out and screen over.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial (detail), Maya Lin, 1982. Washington D.C.. Courtesy, Marita Sturken.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial (detail), Maya Lin, 1982. Washington D.C.. Courtesy, Marita Sturken.

Indeed, nowadays memory is a cultural force to the extent that we can now speak of a “memory boom” expressed in a plethora of objects throughout the world (memorials, memory museums, countermemorials, etc.). Memory studies seems to have been more concerned with certain memories, such as the memory of the Holocaust, the memory in the former Soviet Union republics, or the dictatorships in Latin America, and less about the memory of Slavery or even the rise of public debate about racial injustice (a quick search on the issues of the Memory Studies journal, will show that). This is in the process of changing with the events unraveled by the South African Rhodes Must Fall Movement, in 2015, that triggered a worldwide movement of toppling down colonial statues and dismantling racist monuments, as well as the calls for the decolonization of knowledge, academia, museums, and curricula and the repatriation of looted cultural artifacts. This reckoning with the past is intensifying all across the Americas and in Europe, performed mostly by racial and social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter and Amerindians. Evidently, this is not only about the dead; but also about the living.

What is your take on this “memory activism” wave encapsulated by the toppling down of statues and the dismantling of racist monuments?

The global reckoning with monuments has been amazing to witness, and has been a long time coming. What is fascinating to try and unpack is how, after demands to remove certain monuments and statues have been made for years, decades really, suddenly in the last two years there was a shift and they really started to come down. So it is a powerful example of how counter-hegemonic movements push and push for change and then suddenly there is a moment when the change breaks through. The Rhodes Must Fall movement was an early catalyst but then clearly it was the upheaval of the summer of 2020, with the murder of George Floyd and the rising up of people in response around the globe which meant that suddenly the monuments had to come down, either through vandalism or official decree. I don’t believe that acceleration of change would have happened without the global crisis of the pandemic. The world seemed to crack open in 2020 in part because norms had been so disrupted; suddenly change seemed more possible because everything had changed, there were no norms left.

In the United States, this has largely been a reckoning with the presence of Confederate monuments throughout the South and beyond, monuments that were built not only in the wake of the Civil War but also well into the 20th century in response to moments of racial struggle. The former Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia has finally dismantled the long corridor of Confederate statues along Monument Avenue, which was unimaginable a decade ago. To render that landscape of racist monuments visible, to mark it for what it was saying ideologically, took decades of struggle, and of course it’s not over. There is constant pushback to this change, but there has also been institutional progress. There is now the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which addresses the history of Atlantic slavery, and the Mellon Foundation has embarked a multi-million dollar project on rethinking monuments. And it is not insignificant that corporations felt that they needed to issue statements in support of Black Lives Matter. Part of what we are seeing is change through traditional forms of social protest, and change emerging in new ways through social media and even through brands. In the United States, much of the push for social change is emerging in the previously unlikely place of brand culture, while our political institutions remained mired in outdated norms.

The role of visual culture is powerful here. This is about things that once seen can’t be unseen. This takes us back to the horrific power of the George Floyd video, taken by a 17 year old witness with the presence of mind to keep her mobile phone camera running. That video cannot be unseen. Similarly the message of white supremacy in the monuments in the landscape can’t be unseen or normalized at this point. I have been particularly impressed by some of the public art organizations that have undertaken monument projects, like the Monument Lab in Philadelphia, which does counter-monument projects, and the Paper Monuments project in New Orleans. Both have engaged the public over the last 10 years in rethinking monuments, creating ephemeral monuments, and thinking about who should be honored and remembered. This connects back of course to productive ways in which history can be re-imagined, not as stable but as flexible, debatable, and even ephemeral.

The role of visual culture is powerful here. This is about things that once seen can’t be unseen. This takes us back to the horrific power of the George Floyd video, taken by a 17 year old witness with the presence of mind to keep her mobile phone camera running. That video cannot be unseen. Similarly the message of white supremacy in the monuments in the landscape can’t be unseen or normalized at this point. I have been particularly impressed by some of the public art organizations that have undertaken monument projects, like the Monument Lab in Philadelphia, which does counter-monument projects, and the Paper Monuments project in New Orleans. Both have engaged the public over the last 10 years in rethinking monuments, creating ephemeral monuments, and thinking about who should be honored and remembered. This connects back of course to productive ways in which history can be re-imagined, not as stable but as flexible, debatable, and even ephemeral.

Speaking of “re-imagining” history and of the labor of history as “flexible, debatable, and ephemeral”, in Portugal, memory debates escalated in 2017 after the inauguration of a statue to a 17th century Jesuit missionary in Brazil, Father António Vieira, and the winning proposal for a Memorial to the Victims of Slavery in Lisbon’s city council participatory budget, which propelled, reactively, the resuscitation of an old project – a “Museum of Discoveries”. The debate that followed questioned the dominant national narrative, which is anchored in the exaltation of Portugal’s colonial expansion of the 15th and 16th centuries, known as “the discoveries”. This ongoing public debate is a symptom of an underlying imperial episteme that has survived the end of the empire and the revolution of 1974, which was unable to shatter the Luso-tropical consensus forged under the later years of the dictatorship. This episteme is manifested all across Lisbon and most poignantly in monumental Belém, as Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillout hinted (1995), giving shape to a “visuality complex” that endures. However, there are other narratives, imaginaries, and protagonists. These have been “contained”, to use one of your expressions in a recent article, “Containing Absence, Shaping Presence at Ground Zero” (2020), and blocked from view.

You have been to Lisbon a few times, what do you see when you look at the city’s memoryscape, especially when comparing it with other contexts that you know well, such as the USA, Argentina and Chile? How can one counter-balance the colonial junk and memorabilia and “shape” other narratives onto the cityscape?

One of the aspects of the memory landscape of Lisbon that I have always been struck by is the way that the memory of the 1755 earthquake and tsunami is so embedded into the cityscape. I was startled when people pointed out to me where one could see where the flood waters had risen, for an event that was over 250 years ago. I even had someone tell me that there is a sense in which Lisbon has a “ground zero” because of the earthquake, like New York. Lisbon is a complex memoryscape, and so it is no surprise that it is a canvas on which the legacies of the Portuguese Empire are being fought, with competing monuments, memorials, and museums, one made more complicated by Portugal’s experience of both dictatorship and enforced austerity and its tensions with European identity and economics.

The narrative of the “discoveries” that has so dominated colonial discourse in Portugal is a powerful one. Discovery is such a positive term, as a kind of coming upon knowledge, and also inevitably one that implies a kind of public arena of things, not owned by anyone, waiting to be discovered. As we wrestle around the globe with the legacies of extractive capitalism and the extraction forces of colonialism that have resulted in the climate crisis, that term “discovery” looks even more insidious for what it masks.

This also makes me think that understanding the legacies of colonialism is also about further understanding the materiality of the navigations and colonial imperialism. When I visited the Algarve and learned about the history of the region at Cabo de São Vicente, at the most southwest corner of Portugal and Europe, I was struck that the region had been fought over for centuries because of its coves that sheltered boats from the strong winds as they entered and exited the Mediterranean. I remember thinking, this shows us a certain materiality of that fateful and brutal movement outward from Europe to extract from other parts of the globe. You couldn’t be imperial unless you could navigate the seas but you also had to have control over the wind if you were travelling outward in boats dependent on the wind.

Here, I think that the work by contemporary artists on colonial legacies is so hugely important in visualization the materiality of colonialism. For instance, Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014), which when exhibited in a former sugar refinery plant in Brooklyn managed to tell through art the complex and defining role of sugar in colonialism and capitalism. Or John Akomfrah’s stunning three-channel video, Vertigo Sea, of the history of the Atlantic as a graveyard, from the brutal massacre of animals in the Canadian North to the thousands who died from slave ships to the “death flights” in Argentina, where during the Dirty War young people were drugged and dropped from planes to their deaths in the Atlantic. Portuguese artist Grada Kilomba’s 2017 installation Table of Goods materializes the extracted goods that defined the colonial network of Atlantic slavery, with sugar, coffee, and chocolate, all of which “necessitated” slave labor. Her installation in Lisbon, O Barco (The Boat) (2021) powerfully uses burnt wood to materialize the slave ship, arranged in the pattern of the ship’s hull. This, in the shadow of the monumental (and kitschy) Monument to the Discoveries. This kind of engagement with the material forms of the colonial enterprise is reparative, it reworks those forms not only as elements of critique, but also as sensorial engagements that allow participants and viewers to reclaim those material forms.

Last year you republished your book Thelma & Louise (2000/2020) in the advent of the 30th anniversary of the movie’s release and in the aftermath of the #Metoo movement. I have seen the movie a few times and the final scene always strikes me: when the only option for Thelma and Louise is to drive off “into the infinite” to escape all those men who are chasing them and their “justice” and carceral system. It always reminds me of that classical scene of buffalos falling off the cliffs to their death bellow. Although we want to believe Thelma and Louise make it (and in a way, as you argue towards the end of the book, they kind of do), the fact is that their destiny is the same as those buffalos. In a Patriarchal society, for women that don’t comply, as for other subaltern subjects (including animals), death is often the only way out – if not real death at least social and political death. Thelma & Louise is a film that, thirty years on, still very much resonates in a world governed by gender power relations. And yet, on the other hand, women have been at the forefront of social movements, demanding social justice, human rights, animal rights, ecology, etc., namely in Latin America. For example, the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo in Argentina or the women in Chile as you have tackled in a recent article, co-authored with Katherine Hite, “Stadium Memories: The Estadio Nacional de Chile and the Reshaping of Space through Women’s Memory” (2019), and their pursuit of justice for the thousands of people who were tortured, murdered and disappeared under bloodthirsty political regimes that were nurtured by the United States (the famous Operation Condor).

How can we counter the erasure of “women’s memory” in history, making their experiences, affects and their part in the making of countermemory visible? Can you also expand on the way “women’s memory” was addressed at the Estadio Nacional de Chile?

I think that one of the reasons Thelma & Louise retains a powerful relevance after all these years (there was a huge amount of attention paid to its 30th anniversary) is that the film is ultimately about how the law cannot account for women. As Thelma says, “the law is some tricky shit.” The law cannot deal properly for sexual violence, it does not protect women or offer them agency in relation to sexual assault. Once Louise shoots a man for attempting to rape Thelma, the women have no choice to become outlaws, because they are outside the law that could never read that crime as justifiable. It may be in the era of #metoo that we have made progress in talking about sexual harassment and sexual violence, and there have been some consequences for some high profile offenders, but the fact remains that law has not changed. I argue in the book that when the women drive off the cliff at the end of the film it is meant to be a metaphor for them not dying but escaping from patriarchal law.

As you point out, though most of my work has been focused on the United States, I have done some work on memory in Latin America. I collaborated with Latin American scholar Katherine Hite on writing about memory in Chile, and I regularly teach a course with her in Buenos Aires for NYU. I was also honored to be part of a large collaborative project of scholars and artists in New York, Istanbul, and Santiago, through Columbia University, on Women Mobilizing Memory from 2013-2016 (which produced the book, Women Mobilizing Memory: Performances of Protest (2019), that essay is published in.

The memory projects of Latin America, in particular in Argentina and Chile (also Uruguay and Colombia) have been very powerful interventions into memorialization and memory activism, often primarily led by women. Because many of these memory projects are a response to state terrorism in the 1970s and 1980s, fueled by the United States, the Latin American memory work has also drawn on human rights discourses in ways that are quite distinct from the US.

Argentina is a particularly powerful case study on memory politics because of ongoing prosecutions, the refusal of former military to speak, and, above all, the high numbers of those who were disappeared. All of this has produced a kind of prolonged grief, an extended memory activism, so now the children of the disappeared (HIJOS) are still performing escraches, protests where they call out the perpetrators who are living in plain sight. Women have been at the forefront of the fight for the disappeared since the very beginning, in part because it was felt that in marshalling their status as mothers, they would be less likely to be killed and harassed than the men (this sadly was not true, as some of them were murdered). The Madres de la Plaza de Mayo were enormously influential worldwide in demanding justice – as they have aged the movement has changed, become more overtly political on other issues, and their weekly marches filled with souvenirs and performed for tourists. Nevertheless, the radical nature of their demand to “aparición con vida,”for the state to return their disappeared children alive is a powerful demand. Adam Rosenblatt calls it a “counterfactural demand” – one that obviously cannot be fulfilled, yet in its demand it basically delegitimizes the state, making clear that the state cannot repair what it did. This is why many of the Madres (there are two groups that disagree on demands) refuse to participate in the archaeological identification of remains. As I noted before, many of the dead were disappeared in the graveyard of the Atlantic and will never be found. The battles in Argentina also continue because the military stole the babies of women prisoners who were killed, and they were adopted into military families. Now DNA is being used to find them, with the trauma of people finding out in the 40s that they were raised by the people who killed their biological parents. We see here the brutality of the junta produced generations of trauma.

Chile has its own set of distinct legacies, in which torture and exile were more prominent than disappearance, producing a different set of traumas. The Estadio Nacional strangely had been left unchanged for 40 years after it had famously been used as a site of detention, torture, and death in the months following the coup on September 11, 1973. It was actively used as a stadium and voting site for the decades that followed and the spaces where people had been detained were left to ruin. We went to visit it when renovations were beginning to transform those spaces into memory spaces, and one in particular was the former women’s locker room where the women had been housed together though separate from the men. The stories of solidarity among the women at the stadium were very moving. I was also interested in exploring the question of how stadiums have historically been transformed into sites of violence, how the architecture of the stadium is conducive to repression. There is now a very active set of activities at the stadium around memory, much of it led by a younger generation.

Chile has its own set of distinct legacies, in which torture and exile were more prominent than disappearance, producing a different set of traumas. The Estadio Nacional strangely had been left unchanged for 40 years after it had famously been used as a site of detention, torture, and death in the months following the coup on September 11, 1973. It was actively used as a stadium and voting site for the decades that followed and the spaces where people had been detained were left to ruin. We went to visit it when renovations were beginning to transform those spaces into memory spaces, and one in particular was the former women’s locker room where the women had been housed together though separate from the men. The stories of solidarity among the women at the stadium were very moving. I was also interested in exploring the question of how stadiums have historically been transformed into sites of violence, how the architecture of the stadium is conducive to repression. There is now a very active set of activities at the stadium around memory, much of it led by a younger generation.

So, women and the law. DNA as a marker. Memory as activism and a demand. We see these themes enacted around the globe.

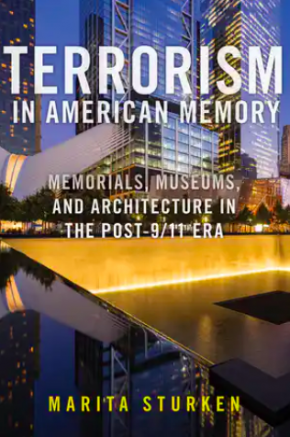

In your new book, Terrorism in American Memory: Memorials, Museums, and Architecture in the Post-9/11 Era (New York University Press, 2022), you examine the role of cultural memory in what you designate as “the post-9/11 era of American culture”, namely by unpacking Ground Zero as a site of “memory tourism and consumerism”, where US memory remains unchallenged and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are erased, and its counter-mirror – the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Alabama, which “rewrites the national script of American history”. This “post-9/11 era”, according to you, begins precisely with 9/11 memorialization and fear of “foreign terrorism” and ends up with battles of racial injustice brought about by the pandemic and state genocide in dealing with Covid-19, culminating with the invasion of the Capitol, in January 2021. In establishing such fruitful entanglements, you rethink the memory of terrorism in the United States, arguing that terrorism was and is practiced not only outside the nation’s borders but also within, from slavery to lynching, to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the way the pandemic was dealt by Trump’s presidency. Terrorism is therefore “a foundational aspect” of US culture and it lingers. By laying down this genealogy you are also repudiating the “narrative of American innocence” and, in so doing, decolonizing US history.

Can you elaborate further on this post-9/11 era and its entanglements so to open the appetite for your upcoming book?

I narrate in the book that I have been working on the material of this book for over 15 years, yet it did not cohere in its argument until the pandemic hit, and the world shut down. It was in that moment that it became clear to me that the post-9/11 era had come to an end, and been replaced by a new, yet to be defined era. This became even more clear with the insurrection at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, when a mob incited by Trump stormed the Capitol and threatened the US democratic processes. The ironies were thick. On September 11, 2001, the Capitol had been the target of Flight 93 that crashed in Pennsylvania. So, we had gone from an era shaped by fears of and brutal responses to foreign terrorism to a time when the nation is under threat from domestic terrorism, at war not with others but with itself.

The post-9/11 era can be defined as the time period in which 9/11 the event, and all that followed in its wake, was the primary shaping aspect of US culture and society. From this one event, shocking a nation oblivious to its capacity to engender hatred for its foreign policy and imperial strategies, emerged a culture of nationalism and excess patriotism, of revenge and Islamaphobia, of fear of the racialized other, of securitization and defense, and a ramped up bellicosity that fueled two wars under the guise of national defense and the “Global War on Terror.” The devastation of the US response to 9/11 has been globally catastrophic, destabilizing the Middle East, resulting in hundreds of thousands dead in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria and beyond, and costing trillions of dollars that fueled the privatized military industry.

I argue that the post-9/11 era was also totally preoccupied with memory, beginning with the excess of 9/11 memory and what it means. There are over 1,200 9/11 memorials throughout the US and beyond, many of them built 10-15 years afterward as the Port Authority (that owns the site) handed out pieces of steel to just about anyone who wanted to build a memorial. So there was a kind of mix of official, unofficial, grass roots, quality to much of what was built, with a broad array of aesthetic styles. I argue that this extended memorialization, which only has a parallel in US history with the memorialization of the Civil War, became less about the event itself and more about a nostalgia for the moment of national unity that followed the attacks. 9/11 memorialization has largely been an uncritical process of national exceptionalism, one that affirmed narratives of American innocence, of the nation attacked out of the blue.

In the book, I examine the museum and memorial that were built at Ground Zero in New York, and the architectural rebuilding of lower Manhattan, which represented a stunning transfer of $25 billion of mostly public funds to the private sector, resulting in a few uninspired skyscrapers and a cathedral-like shopping mall/transportation hub. This is sadly a neoliberal triumph that provides no actual public space. So the book is in part about the failures of the memorialization and rebuilding process in New York in particular that exposed the city’s lack of civic infrastructure.

The preoccupation with memory in this era is also part of what signals its end, since by 2018 engagement with memory had turned from nationalism to counter memory and critique. I end the book with a chapter on the lynching memory (the National Memorial for Peace and Justice) and the Legacy Museum that were created by Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, Alabama. It is crucial to point out that this is a memory project created by a legal advocacy organization that defends people who have been wrongly accused or unfairly sentenced. Yet it was through memory that Stevenson thought that he could have the most impact in changing broader social ideas about race and criminal justice. And so, in creating a memorial for over 4,400 people who were lynched, and a memory museum connecting the slave trade to segregation, lynching as racial terrorism, and mass incarceration, EJI is deploying memory and practices of memorialization to explicitly intervene into the national story about race and racial progress. We could also say that there is a similar tactic at work when at Black Lives Matter protests people chant “say their names”; here they are engaging in a practice of memory that draws on the long history of reading the names of the dead at memorials. “Say their names” is a demand to see those people killed by police as individuals, whose lives mattered, and also a demand that they be mourned as grievable lives, that they be made whole somehow in recognizing them after death. It is striking that it’s memory, rather than history, that is being deployed as activism there.

In its design, the lynching memorial creates discomfort for visitors that situates them in a kind of complicit subject position. It consists of over 800 Cor-ten steel markers on which are inscribed the names of those who were lynched. As one walks through the memorial, the pathway descends so that the markers loom over one’s head, creating a tension and also placing us in the position of those who looked up at the lynched figure who was almost always elevated above a crowd in order to be seen. This kind of memorialization, that critiques the nation and rejects narratives of national innocence, is a radical intervention in US memory culture.

In addition, the Legacy Museum, as an activist museum, can be seen as a memory museum rather than a history museum. It deploys technologies of reenactment and present-making to bring the memory of slavery, for instance, into the present. It argues that the past is present now, not as history but as memory, that the legacies of slavery exist now in the mass incarceration of blacks. Memory is a more fluid temporally than history, which in museum contexts is defined as separate in the past. (Here I am indebted to Alison Landsberg’s work on the museum.) The Legacy Museum argues that slavery evolved rather than ended, that it exists within the present in new forms, that it is not history.

To return to importance of materiality, I would note that one of the most powerful aspects of the EJI memory projects is the Soil Collection project, in which volunteers collected soil from sites where people had been lynched. The soil, which is richly textured and of many varying colors, is displayed in glass jars with the name of the person lynched, place, and date. This is a reclaiming of the soil as memory, to say that the soil belongs to those who bled into it, whose sweat saturated it. Lynching victims were often left hanging on display for days as a form of racial terrorism. The soil is a reminder that racial injustice is often enacted over land ownership. Participants in the gathering of soil sometimes used the language of DNA to characterize the possible trace of the dead in the soil, that it signifies a claiming of the land through the comingling of body and dirt. The dirt itself also stands as a kind of testimony of nature, signifying that the categories of race and the ideology of white supremacy are not natural. This very simple act, of collecting the soil, is a deeply reparative one.

I believe that the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice signal a way forward in terms of wrestling with difficult and painful pasts, a new era in which increasing demands are made to confront difficult legacies in order to move beyond them, a new era that has some possibilities of reparative memory. This will involve contestation and pushback, it will progress through fits and starts, but there is a certain way in which there is no turning back after these last few years. The statues have been dismantled.

The Lynching Memorial (The National Memorial for Peace and Justice), Equal Justice Initiative, 2018. Montgomery, Alabama. Courtesy, Marita Sturken.

The Lynching Memorial (The National Memorial for Peace and Justice), Equal Justice Initiative, 2018. Montgomery, Alabama. Courtesy, Marita Sturken.

I like this idea of “reparative memory”. What are you working on now? What is your next research project?

I have decided to return to photography to work on a project I have touched on, off and on, over the years, the history of amateur/personal photography. I am interested in how in the 20th century Kodak and then Polaroid were hugely powerful in shaping how consumers used cameras and the kinds of pictures that they took and kept. I feel like we have not truly grappled with the dramatic change that the smart phone camera and social media have produced in personal photographic practices. We take vast numbers of images, we share them constantly, we accumulate mundane pictures, we rarely have an image today that constitutes a special “Kodak moment.” I am interested in examining the history of how people used photographs to create individuality and participate in modern society, and how the relationship to photography has dramatically changed in the digital era, so from Kodak to Polaroid to Instagram. What do people do with their pictures, and how do they gain agency through them?

Of course part of what we see in this digital context is a collapse of the distinctions between amateurs and professionals, as the photos and videos of police violence, so important to the recent broadening of public understanding of police killings of unarmed black people, have been taken by ordinary people. It has transformed society for people to always have a camera (on their phone) with them. The history of personal photography has always been about abundance and mobility, but this has been so dramatically augmented in the last 15 years (hard to remember that the smart phone only dates from 2007). I believe that the relationship of photography to memory has changed fundamentally in this time period as well, since how we use images to remember is now dominated by how we share them. In many ways we have very little understanding of these remarkable changes in how people use photography today. This is often characterized in negative terms about selfies, narcissism, data surveillance, and the negative effects of social media, but I want to explore the new forms of agency it has provided. In some sense, I suppose you could say that within the critiques my work has involved, I am always seeking out forms of reparation.

Thank you so much, Marita, for the generosity of your time.