Why Do I Need to State the Obvious - Installation by Edgar de Oliveira / Avital Barak

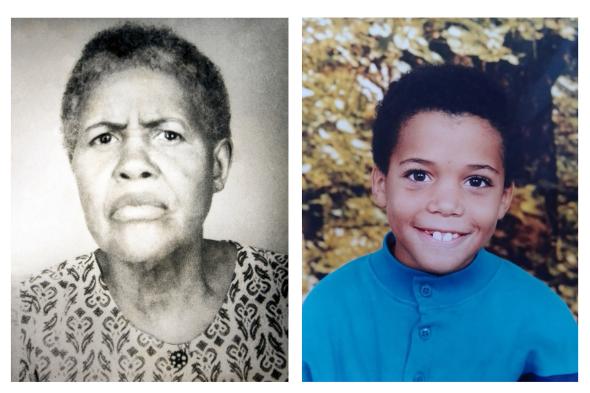

When Edgar first spoke to me about his project, he began with Amélia, his paternal grandmother. Amélia Batista Monteiro was born in Mozambique on 10 October 1907. Her mother was Mozambican, and her father was from Goa, in India. She had eight children with three different husbands, two of whom were Portuguese soldiers who had served in Mozambique during the First World War. These eight children had 47 grandchildren. Edgar belongs to the second generation of Amélia’s descendants; in total, there are now five generations. This extended family is spread across three continents and 16 countries worldwide, comprising people of various ethnicities and nationalities.

Edgar was born in Mozambique in 1973. Following the country’s independence, he and his family were, like everyone else, asked to renounce Portuguese nationality and become Mozambican citizens. However, as civil war broke out soon after independence, Edgar’s parents decided to keep their Portuguese citizenship and leave the country, moving to Portugal. Some of Edgar’s relatives also relocated to Portugal during this period, while others remained in Mozambique. Then there were many other movements, from Mozambique to other countries in Africa, Europe, and North and South America.

Looking at pictures of this family, it is hard to believe that they are all related and descended from the same woman. But why should that be surprising? After all, this is precisely what has happened to humanity as a whole. This is the starting point of the project Why Do I Need to State the Obvious, a multimedia installation functioning both as an archive for Edgar’s family and as an exploration of questions of identity, belonging, and the consequences of geopolitics and colonial history on the mobility of people and the structure of families in the present day.

Identity

In today’s world, everything is about identity. Both the right and the left understand and act according to this paradigm. Looking at the global political landscape, it is clear that politicians across the spectrum are exploiting the concept of identity politics — which emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s in response to dramatic changes in the world and the urgent need to open up public discourse to diverse voices and perspectives — for their own narrow purposes. Identity has been weaponised by the right wing against minorities and has fractured solidarity on the left, as it produces fragmentation.

But identity is not a single, fixed thing; it is always complex, plural, and sometimes contradictory. One can be born in Mozambique, grow up in Portugal, have a light skin complexion, and yet not feel a sense of belonging to any place. One can have a grandmother in Mozambique who had eight children, some of whom were soldiers in the Portuguese army, while others supported the liberation movement against Portugal. One family, many political positions, many identities.

Amélia’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren speak many languages, have different hair colours, and hold many different passports. They have lived a wide range of experiences. Yet they are all part of the same family. When they meet, they share a sense of belonging to something beyond words, categories, or distinctions. So what is this family identity? Who knows? Even the family members themselves offer many different answers to that question.

Mobility

Mobility encompasses not only physical human movement, but also the conditions in which it occurs. Above all, mobility is a category that differentiates between people, marking their civic status and socio-economic position. It reveals whether someone belongs to the prosperous part of the world or to the part that is exploited and excluded from resources and power. Mobility also tells us something fundamental about human life. People move from one place to another. They always have, and they always will.

People move from one country to another for many reasons: because of political situations, in the search for better opportunities, for love, because they have been expelled, or because they are running for their lives. People move because they want change, because they believe that life will be better on the other side of the sea. Often, they later discover that this is not necessarily the case.

Then there is the question of who can move, and how. When you are young and do not have a family to take care of, it is often easier to move. At the same time, age itself can restrict mobility, as in the case of the Israeli movement regime that controls and limits the movement of Palestinians in Palestine, both in the occupied territories and when they try to enter Israel. This is particularly true for young, unmarried Palestinians between the ages of 18 and 35. Another example, out of many, is the American visa regime. Try applying for a tourist visa to the United States if you are 23 years old, from the Middle East, and have no stable job or contract at home.

There were periods in the past when borders were relatively open, and large-scale immigration reshaped the world. In the last twenty years, millions of people have moved from one side of the world to the other, looking for a better life or escaping persecution. At the global level, particularly in the West, right-wing populist leaders mobilise the metaphor of invasion to gain power, framing as a threat the very people whose countries were once colonised for profit and who were later recruited to perform the hardest and most undesirable labour.

We have become accustomed to hearing about immigrants and refugees, whether framed as “news from the heart of the crisis” or as individual traumatic stories. We think about colonisation and settler colonialism, about slavery in the past and the global economy of today. These are all concepts, phenomena, and narratives of movement. Behind each of them lies the mobility of people — whether chosen or forced, in response to events or as an attempt to begin a new life.

In Edgar’s family, one can find the full spectrum of reasons for moving from one place to another. It begins with Amélia’s father: although the specific details of his journey remain uncertain, we know that he moved from Goa to Mozambique. Both were Portuguese colonies, connected by imperial trade routes that involved the circulation of goods, labour, and enslaved people. Amélia’s partners were Portuguese men who arrived as soldiers of the empire. Later, some of her children felt more Portuguese, others more Mozambican. Over time, new reasons for migration emerged, and the family gradually spread across Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

Family

So what makes a family a family? Is it purely genetic — a lineage that can be traced back to a shared ancestry — binding together people from different places, languages, and lives? We know that emotional bonds and collective memory play an important role in blood relationships. At the same time, the family is also an economic unit and, in many ways, a microcosm of the society in which it exists.

We hold fixed ideas about how a family should function, yet families are shaped by the values and social conditions of their time. The nuclear family, as we understand it today, is a modern invention, as are many of the relationships within it. Over the past five hundred years, family structures have undergone profound transformations in response to the rise of capitalism and industrialisation. The Industrial Revolution, in particular, reshaped domestic life: the roles of women changed, the place of children shifted, and these dynamics continued to evolve again and again.

Technology now directly affects family life, especially the ability to remain connected when relatives are spread across the globe. As part of his project research, Edgar created a WhatsApp group that quickly became the family’s main gathering space. Members from different generations and locations began sharing memories and reconnecting. Long-standing dynamics and internal politics surfaced, and a renewed sense of belonging emerged. Later, Edgar organised a family picnic in Moita, Setubal district, bringing together relatives from around the world for the first time.

Edgar’s family is a direct product of Portugal’s past and present: its colonial history, ongoing economic struggles, and racial tensions, but also its complex cultural entanglements. These were formed over centuries of colonisation by a small country across vast territories. As always, the influence moved in both directions. The former empire now occupies a tiny space compared to its former colonies. In the installation, this historical anomaly becomes palpable — how such a small nation ruled such immense territories for so long. We know the answer, of course, yet confronting its scale remains deeply unsettling.

Returning to the beginning of this text, although Amélia’s family offers a powerful representation, it is not a unique phenomenon. As already suggested, this is how humanity has evolved and become what it is today. People have always moved, integrated with other groups, and settled in new territories. Humanity began in Africa and gradually spread across the globe. There are countless families that reflect this same mixing of histories, like Edgar’s.

So why do we need to state the obvious? Why do we still have to insist that every human being is born equal — with the right not only to live, but to move freely, to pursue happiness, to grow and develop, to have a future, and to be free?

** The first phase of Edgar de Oliveira’s project, ‘Why Do I Need to State the Obvious’, will open at Casa do Comum on 5 March 2026.