Revisiting the years when Pancho Guedes lived in Mozambique: The arts and the artists

At the time, Mozambique was a closed and ideal world in which there was only good news, inaugurations and speeches from the Império (Empire). It was a world of rumours, secrets, gossip and an ever-growing web of informers and agents, but where, in spite of everything, anything seemed possible.

Amâncio d’ Alpoim Guedes[1]

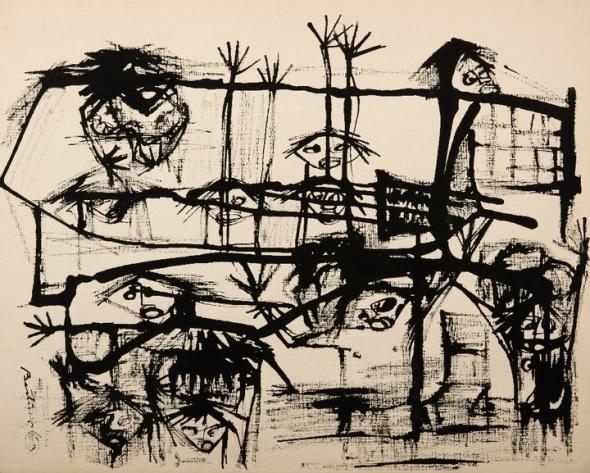

Bertina Lopes, Sem título, desenho, 1963

Bertina Lopes, Sem título, desenho, 1963

Pancho Guedes (born in 1925), architect, painter, sculptor, collector and patron, played an important cultural role during the years he lived in Mozambique. This is true because of his own work, which brought together several worlds, as well as for his role as mediator between artists of all traditions, the wider public (local and international), and the institutional artistic world, which he had access to at the time. This role, carried out between the centre and the margins, was subject to controversy, had a profound effect on Mozambican art history. This exhibition offers many opportunities to widen the knowledge of the arts and artists of this period, and at the same time, throws open other possible paths of study in this area. This text is intended as a contribution in that direction, and also aims at stimulating the emergence of other voices and perspectives in the research and writing of that history.

The creation of the Núcleo de Arte in the colony

The idea of creating the African Empire, which the Estado Novo was set on, triggered profound changes (mainly from the 1930s onwards) in the then Portuguese colony of Mozambique. In a reality characterised by great inequalities and varying governmental presence, the capital city of Lourenço Marques (currently Maputo) and the city of Beira, where most administrative services and, gradually, an ever greater number of human and economic resources were gathering, were both gaining prominence. Mozambique was being “built” amidst its ongoing relations with neighbouring countries, in particular, South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), as well as its connection with Portugal.

It was in this colonial environment that a very small number of workers, teachers and self-employed professionals that were artistically inclined, or who had an interest in culture and the arts, developed and gave life to a discreet cultural movement in the capital and other places. One or two became interested in African art and started collecting it, even when a lack of artistic education prevailed. “They call the artistic images dummies!” and “what is most surprising is that cultured people also call them dummies!”, complained Felisberto Ferreirinha.[2] Thus, two “types” of artists began to develop, coexist and interact, especially, but not exclusively, in the cities that were being built: the African artist, whose work took shape in a multiplicity of small, personal and domestic objects, as well as through several sculpturing traditions and the artist (European, and later African too) who used new methods and processes to create art, resorted to new materials and played a different social role. We will deal with some aspects of this relationship, coexistence and interaction below.

Abdias Muhlanga, A Cerca, 1962In 1936, some of these individuals were involved in the creation of the Núcleo de Arte da Colónia de Moçambique, which was set up in the city of Lourenço Marques with the aim of spreading aesthetic education and promoting the progress of art in the colony. According to the association’s statutes, its job was to organise art courses, put on art exhibitions, create an art museum (with an indigenous art section), and organise visits by artists from Portugal, who could create works of art in the colony inspired by local subjects. It was also its job to organise art exhibitions dealing with Mozambican subjects in Portugal and contribute, in every possible way, to the artistic exchange between Mozambique and the metrópole. Its sections included: Architecture, Fine and Decorative Arts; Music and Choreography; Theatre; Literature and History of Art; Indigenous Art and Ethnography and also Propaganda and Publicity. In the event of a situation not being covered by the association’s statutes, the statutes of the metropóle’s Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (Portuguese Fine Arts Society) would apply. The creation of the Núcleo de Arte was clearly the embodiment of imperial thinking and of the attempt to build closer relations between Portugal and its colonies, as were the large-scale propaganda campaigns carried out at the time[3]. Its actions and importance in the colony, however, spread far beyond those interests, as we will see

Abdias Muhlanga, A Cerca, 1962In 1936, some of these individuals were involved in the creation of the Núcleo de Arte da Colónia de Moçambique, which was set up in the city of Lourenço Marques with the aim of spreading aesthetic education and promoting the progress of art in the colony. According to the association’s statutes, its job was to organise art courses, put on art exhibitions, create an art museum (with an indigenous art section), and organise visits by artists from Portugal, who could create works of art in the colony inspired by local subjects. It was also its job to organise art exhibitions dealing with Mozambican subjects in Portugal and contribute, in every possible way, to the artistic exchange between Mozambique and the metrópole. Its sections included: Architecture, Fine and Decorative Arts; Music and Choreography; Theatre; Literature and History of Art; Indigenous Art and Ethnography and also Propaganda and Publicity. In the event of a situation not being covered by the association’s statutes, the statutes of the metropóle’s Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (Portuguese Fine Arts Society) would apply. The creation of the Núcleo de Arte was clearly the embodiment of imperial thinking and of the attempt to build closer relations between Portugal and its colonies, as were the large-scale propaganda campaigns carried out at the time[3]. Its actions and importance in the colony, however, spread far beyond those interests, as we will see

In this context of relationship building between Portugal and the colonies [4], the sculptor Jorge Silva Pinto travelled to Mozambique as the first artist the Núcleo de Arte invited to visit the colony. Invited to work with local motifs, he ended up settling down and becoming a teacher in technical education, giving a boost to the drawing course that was already being run. In 1938, he presented the first works that had been carried out in Mozambique to the public. In the city newspapers, the colonist population praised the curators, the sculptor and the exhibited works. The same would happen a few years later with the first exhibition of Frederico Aires, a naturalist painter who excelled at landscape and history painting. “Readers, rejoice! There’s a painter in Lourenço Marques! A painter who’s made a name for himself”, wrote Sobral de Campos.[5]

Among the colonized Africans, the policy in force distinguished between the assimilados (assimilated) and the indígenas (indigenous). This distinction reproduced the racial, social and cultural discrimination that was part of the colonial situation and which created different possibilities of integration in the colonial society. For the educated and cultured generations of non-whites, of mulatto and black assimilados, who emerged in this context and had the possibility of expressing their opinions in the newspapers, the reaction was also favourable. At that time, the recognition and defence of African artistic production were not considered impediments to the learning of western art. The first art exhibitions that were organised in the colony were seen as “progress for the country and for the Africans”. Together with the “in-depth study of African folklore”, they paved the way – or so it was believed at the time – for the emergence of an artistic synthesis.

arquitecto pancho guedes

arquitecto pancho guedes

Art and African artists

During the ‘50s and ‘60s there was something restless and extraordinary about the beautiful city that the Portuguese had built in less than fifty years and which they called Lourenço Marques.

Amâncio d’Alpoim Guedes[6]

With the end of the Second World War, there were new political changes. The imperial thinking of the Estado Novo was replaced by a new phase which was heavily influenced by international political pressures. The multi-continent and multiracial nation was created, although official policies and practice remained almost the same. In the following years, there was a vast programme of investments in the colonies which resulted in an increase in the colonist population. More specialised job vacancies, greater supply and better working conditions attracted a considerable number of professionals to Mozambique, who ended up settling there and contributed to the development of a new environment. Architects, artists, teachers, critics and entertainers, among other professionals, consolidated the aesthetic and ideological values of the Movimento Moderno (Modern Movement), until then only a timid presence, and influenced what was to happen in many areas of life in the colony.

It was to this city that Pancho Guedes, the young man who wanted to be a painter and who had just finished an architecture course in South Africa, returned and started to work. In terms of public building, the city was going through a transitional phase, moving from modernist expression to a new language imposed by the state which was historicist and monumental.[7] At the same time the general urbanization plan for the city, which had been developed in Lisbon, was being implemented. Needless to say there were enormous obstacles to achieving this. Gradually, in the following years, a local Modern style was developed, to which several architects were associated and which has been the subject of study.

The Núcleo de Arte, which some of the city’s architects belonged to, was also undergoing changes. The association wanted to re-launch itself and was seeking exchanges with South Africa, Portugal and other countries. João Ayres (1921-2001), son of the painter Frederico Ayres, arrived in 1946, and put on an exhibition the following year. His work drew attention because of how different it was to what was being produced in the city at the time. He painted local subjects of a social nature, which were related to the theme of work, particularly work on the docks.

It was in this context that the Núcleo had new statutes approved, and expanded and adjusted its sections. It included cinema and created an art theory and criticism section. The drawing, painting and sculpture courses run by Frederico Ayres, João Ayres and Silva Pinto restarted. Its sections were active and met regularly. The debates that were organised about academic and modern art involved various intellectuals and artists. At the time there were over one hundred members. The association’s lack of premises continued to be an issue, which was only solved years later with the support of the Gulbenkian Foundation. Amongst the students were several youngsters and aspiring artists who would intervene on several fronts in the following years. It is important to highlight that in 1949 the Núcleo de Arte organised the 1st General Mozambican Fine Arts Exhibition. Its intention was to gather all those involved in the visual arts, the length and breadth of the country. Among the large number of participants were Luís Polanah, José Lobo Fernandes, José Freire, José Soares, Antero Machado, João Paulo, Alfredo da Conceição and António Bronze. Joaquim Azevedo Júnior, Arnaldo Silva and Carlos Alberto Vieira were some of the photographers who participated.

At the end of the 1940s, in a context where colonialism was already being questioned and there was greater assertion of African artistic traditions, the number of Africans who turned to drawing, painting, caricature, illustration or photography was very small. Luís Polanah is perhaps the best example of this. The absence of “coloured artists in Mozambique”, or rather, of qualified artists, who had done a painting or sculpture course to perfect their vocation, was remarkable. Attention was also drawn to the “collective art” of the indigenous people, some of whom were serious cases of ignored talents, such as the Maconde sculptors. Gathering these ignored or recently discovered talents who had not been to art schools, the “coloured artists” in particular, in an exhibition, was seen as a necessary stimulus for Mozambique’s artistic culture. In 1949, Felisberto Ferreirinha, who had long been interested in African art, exhibited his Maconde sculpture collection and delivered a lecture on the subject at the Sociedade de Estudos. In the North of Mozambique, where he had lived for some years, he had come into contact with other forms of art, which he thought to reveal more “primitivism” than the work of the Maconde. He had acquired more recent works, which he considered as less “genuine and valuable”. He raised the issue of the future of African art and shared some of his fears about its possible “Europeanization” or disappearance with his contemporaries.[8]

Tito Zungu, Avião, África do Sul, 1970

Tito Zungu, Avião, África do Sul, 1970

The need for an art school to develop the interest and vocations among Africans (and others) was highlighted several times. Illustration or poster design and working with newspapers seemed to be the only future for these youngsters. The exception was Bertina Lopes (born in 1924), who was half European and half African, had studied fine art in Portugal and then returned to Mozambique, where she was a teacher and an active artist. The exception she represented did not alter the situation much, but in the following years there were some changes. Youngsters from the cultured minority of the colonised population, but also children of colonists who would not accept the colonial situation started getting involved with various cultural initiatives in the capital and other parts of the colony. In the following years, the winds of change and the development of nationalism and anti-colonialism created more opportunities for intervention, participation and reflection about the search for an African and even Mozambican expression. The reflections of Aníbal Aleluia and José Craveirinha on this topic are an important reference.

Maputo, September 2010

[1] Recollection of the painter Malangatana Valente Ngwenya when he was still young. In Navarro, J. (org.) (1998). Malangatana (pp. 9-14). Maputo: Editorial Ndjira.

[2] Ferreirinha, F. (1933) Da importância social da arte. O Ilustrado 17, 23/12/33, p. 404-5; 409.

[3] For example, the 1st Portuguese Colonial Exhibition in Porto (1934), the 1st Colonial Art Exhibition in Portugal (which used the Colonial Exhibition as a model), and the Portuguese World Exhibition (1940).

[4] In 1937 the 1st Exhibition of Portuguese Art in the colonies took place in Lourenço Marques. It was an initiative of the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes and the branch office of the Lisbon Geography Society.

[5] Itinerário n. 21, October 31st, 1942, pp.4-5.

[6] Idem, ibid., p.9.

[7] See Ferreira, A. F. (2008) Obras Públicas em Moçambique. Lisbon: Edições Universitárias Lusófonas.

[8] In 1949 Felisberto Ferreirinha returned to Portugal (Espinho), where he died a few years later. What happened to his collection?

[9] Pancho Guedes interview by Ulli Beier. In Guedes, P. (org.) (2009) Pancho Guedes. Vitruvius Mozambicanus. Lisbon: Museu Colecção Berardo.

[10] A Tribuna, May 5th, 1963.

[11] O Papagaio; Grupo com um morto; Pescadores; Carroças; Ciclistas; Fotografia de uma família; Homem atirando uma pedra (A Pedrada); Duas mulheres com um menino; Bóias e homens-meiodia e Crucifixo.

[12] Personal communication, March 10th, 2003.

[13] Gladiador; Batalha Naval; Galera; Composição Geométrica and Aurora.

[14] Pancho mentions Gonçalves Diogo, Filipe and Augusto Samuel, among others, as having collaborated on the murals, made several pieces in wood and embroidered many drawings.

[15] Notícias, January 14 th, 1960, last page; p. 9.

[16] Notícias, August 20 th, 1961.

[17] The Museu Nacional de Arte, Museu-Galeria Chissano, the Galeria de Malangatana, and one or two other collections, have works by Abdias and Augusto Naftal.

[18] A Tribuna, March 17 th, 1963, p. 6.

[19] According to Shikhani and, recently, confirmed by Malangatana. In 2007, I tried, and failed, to locate him.

[20] Notícias, 5th April, 1962, p.6, last page.

[21] From 1959 up to 1962 when he left Mozambique and went to live in South Africa. During the period he worked at the Notícias newspaper, he wrote about art and culture. He returned to Mozambique after independence. He continued working in these fields.

[22] Conversation between Júlio Navarro and Malangatana about Chissano. Sunday, 27th February, 1994.

[23] Tempo n. 804, 9th March, 1986, pp.47-54.

in As Áfricas de Pancho Guedes, ed. CML/Sextante, catálogo que acompanha a exposição com o mesmo nome comissariada por Alexandre Pomar, e organizada pela Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, no Mercado de Santa Clara (Lisboa), 17 december 2010 to 8 march 2011.