Museums: the ultimate contact zones

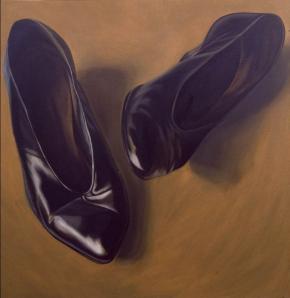

Shoes | 1994 | Teresa Dias Coelho (courtesy of the artist)On the 24th of August 2007, ICOM, the International Council of Museums, created a definition of the museum as its ‘mission’ and ‘backbone’. We can begin there. “A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment”.

Shoes | 1994 | Teresa Dias Coelho (courtesy of the artist)On the 24th of August 2007, ICOM, the International Council of Museums, created a definition of the museum as its ‘mission’ and ‘backbone’. We can begin there. “A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment”.

The definition has nothing in particular to distinguish it. It could be applied to other cultural institutions. Perhaps conscious of setting a low bar, the current leaders of ICOM proposed revising the definition. They handed the task over to a committee: the Museum Definition, Prospects and Potentials Committee. This sought to offer a critical, contemporary perspective and to move towards a definition with a broader international scope. According to an ICOM note published online, “this committee engaged in a broad dialogue, and sought input from all ICOM members around the world. In July this year the committee presented a museum definition to be put to the vote”:

Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people. Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.

These sentences are fuzzy, and linguistically and semantically dry. The content of the new definition is somewhat vague and flabby, and does not meaningfully depart from the old definition. Still, it has provoked internal debate in ICOM. Resistance from some countries, including Portugal, led to the postponement of a resolution to adopt the new definition.

A group of disenchanted members rejected it on account of what they saw as its activist bias. For this group, a museum should be limited to the conservation and investigation of works, in a context of continuity, free from epistemic upheaval. The museum should be the privileged site of museologists and art historians.

Around 1960, the emergence of the discourse of multiculturalism obliged Europe to rewrite its narratives. Informed by the work of Cultural Studies, emergent artistic pedagogy in modern and contemporary art galleries and museums, feminist discourses around gender, and new approaches to post-colonial problematics, museums had to come up with new methodologies of interpretation and communication.

So, when in 2007 ICOM produced a new definition of the mission of museums, it was already outdated. 2007 was the bicentary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. It was no longer possible to put off a reflection within museums on the imperial past, and to develop alternative, ‘de-Europeanized’ modes of knowledge. Museums have a fundamental mission to disseminate such material and symbolic knowledge.

Both the 2007 definition, and the attitude of those who rejected the new ‘activist’ definition rely on a congenital stasis. They reek of a fear that people with interdisciplinary approaches to research, knowledge production and communication might ‘occupy’ museums, open them to the public and elicit debates that will evade the watchful eye of museologists. This is the phantom that haunts today’s museums. Museums are key tools and forums for debating the present by looking at the past. But they cannot rely on a vision that fixes exclusively on the past, as if vision itself were not conditioned by the epistemology, knowledge and experience of the present.

In 1953, a poster for the Musée de l’Homme in Paris declared: “Do a tour of the world in two hours in the Museum of Man”. Other museums making the same claim would have to reduce the time slot. But what world is this? The temporal world of the creation of ICOM is not the same as today’s. The world has moved on and museums have changed – with or without predetermined plans. The museum is, among other things, multiple and diverse. It is a point of view on a world from which it is neither alien, nor distant. In its narratives and in its terminology it curates cultural and artistic relations, distinct knowledges and distinct modes of classification. This final aspect, indeed, is a particular mission of museums: to undertake an epistemological revision of classifications. Museums of ethnography, many of them constituted by works appropriated by the agents of former empires, can no longer merely reproduce the status quo. We can even ask whether, if museums do not change how they look at ‘the other’, the ‘primitive’, they will disappear. Because decolonization is happening in contemporary Europe.

Museums are not free from social intervention. They are subject to the debates of their time. For instance, there has been a controversy recently in Holland over the use of the term Gouden Eeuw (Golden Age). This term does not do justice to all of those who were exploited during the Atlantic slave trade and the expansion and commerce of the Dutch (in the words of Tom van der Molen, curator of the 17th century collection of the Amsterdam Museum). On the other hand, the Rijksmuseum, a significant Dutch museum, not long ago opened up a debate about the use of the term ‘negro’ in some old picture captions. They argued that they should continue to use the term, and simultaneously present a massive exhibition about slavery. These debates positively and urgently go beyond the limits of any mission statement. They carry with them a plural concern with social intervention – the phantom of activism. If this phantom really were exorcised, it would spell the end of neighbourhood museums, community museums and museums of Memory, whose very essence is as places that welcome, address, investigate and communicate all the practices, objects and memories of struggles and political activism.

All of this is not to mention the emergence of the concept of post-museums, developed by Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, who differentiates them from museums of a mainstream typology in their deployment of new forms of architecture and display that go far beyond the vitrine and the displaycase. Focussing on their relationship with the community which they inhabit, they articulate the power relations present in the arts and in objects of worship. They incorporate multiple epistemologies, basing their programming on workshops, and promoting the democratization of curatorial power.

Museums are ever more transnational. They can and must contribute to, and act as instruments of Global History. To that end, they should welcome external social and cultural interventions. Museums are assemblages of images. Their resources endow them with the energy to intervene in, and deconstruct, the interminable flow of images, and see them as more than just banalities, distractions, or entertainment. Museums are unique contact zones. It would be a regression of civilization for museologists, for fear of opening up knowledge, to lock museums away in dungeons, with the keys held by their own, closed guilds.

The author is a member of ICOM

On the 24th of August 2007, ICOM, the International Council of Museums, created a definition of the museum as its ‘mission’ and ‘backbone’. We can begin there. “A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment”. 2 memoirs.ces.uc.pt The definition has nothing in particular to distinguish it. It could be applied to other cultural institutions. Perhaps conscious of setting a low bar, the current leaders of ICOM proposed revising the definition. They handed the task over to a committee: the Museum Definition, Prospects and Potentials Committee. This sought to offer a critical, contemporary perspective and to move towards a definition with a broader international scope. According to an ICOM note published online, “this committee engaged in a broad dialogue, and sought input from all ICOM members around the world. In July this year the committee presented a museum definition to be put to the vote”: Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people. Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing. These sentences are fuzzy, and linguistically and semantically dry. The content of the new definition is somewhat vague and flabby, and does not meaningfully depart from the old definition. Still, it has provoked internal debate in ICOM. Resistance from some countries, including Portugal, led to the postponement of a resolution to adopt the new definition. A group of disenchanted members rejected it on account of what they saw as its activist bias. For this group, a museum should be limited to the conservation and investigation of works, in a context of continuity, free from epistemic upheaval. The museum should be the privileged site of museologists and art historians. Around 1960, the emergence of the discourse of multiculturalism obliged Europe to rewrite its narratives. Informed by the work of Cultural Studies, emergent artistic pedagogy in modern and contemporary art galleries and museums, feminist discourses around gender, and new approaches to post-colonial problematics, museums had to come up with new methodologies of interpretation and communication. MUSEUMS: THE ULTIMATE CONTACT ZONES 3 memoirs.ces.uc.pt So, when in 2007 ICOM produced a new definition of the mission of museums, it was already outdated. 2007 was the bicentary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. It was no longer possible to put off a reflection within museums on the imperial past, and to develop alternative, ‘de-Europeanized’ modes of knowledge. Museums have a fundamental mission to disseminate such material and symbolic knowledge. Both the 2007 definition, and the attitude of those who rejected the new ‘activist’ definition rely on a congenital stasis. They reek of a fear that people with interdisciplinary approaches to research, knowledge production and communication might ‘occupy’ museums, open them to the public and elicit debates that will evade the watchful eye of museologists. This is the phantom that haunts today’s museums. Museums are key tools and forums for debating the present by looking at the past. But they cannot rely on a vision that fixes exclusively on the past, as if vision itself were not conditioned by the epistemology, knowledge and experience of the present. In 1953, a poster for the Musée de l’Homme in Paris declared: “Do a tour of the world in two hours in the Museum of Man”. Other museums making the same claim would have to reduce the time slot. But what world is this? The temporal world of the creation of ICOM is not the same as today’s. The world has moved on and museums have changed – with or without predetermined plans. The museum is, among other things, multiple and diverse. It is a point of view on a world from which it is neither alien, nor distant. In its narratives and in its terminology it curates cultural and artistic relations, distinct knowledges and distinct modes of classification. This final aspect, indeed, is a particular mission of museums: to undertake an epistemological revision of classifications. Museums of ethnography, many of them constituted by works appropriated by the agents of former empires, can no longer merely reproduce the status quo. We can even ask whether, if museums do not change how they look at ‘the other’, the ‘primitive’, they will disappear. Because decolonization is happening in contemporary Europe. Museums are not free from social intervention. They are subject to the debates of their time. For instance, there has been a controversy recently in Holland over the use of the term Gouden Eeuw (Golden Age). This term does not do justice to all of those who were exploited during the Atlantic slave trade and the expansion and commerce of the Dutch (in the words of Tom van der Molen, curator of the 17th century collection of the Amsterdam Museum). On the other hand, the Rijksmuseum, a significant Dutch museum, not long ago opened up a debate about the use of the term ‘negro’ in some old picture captions. They argued that they should continue to use the term, and simultaneously present a massive exhibition about slavery. These debates positively and urgently go beyond the limits of any mission MUSEUMS: THE ULTIMATE CONTACT ZONES 4 ISSN 2184-2566 MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra. statement. They carry with them a plural concern with social intervention – the phantom of activism. If this phantom really were exorcised, it would spell the end of neighbourhood museums, community museums and museums of Memory, whose very essence is as places that welcome, address, investigate and communicate all the practices, objects and memories of struggles and political activism. All of this is not to mention the emergence of the concept of post-museums, developed by Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, who differentiates them from museums of a mainstream typology in their deployment of new forms of architecture and display that go far beyond the vitrine and the displaycase. Focussing on their relationship with the community which they inhabit, they articulate the power relations present in the arts and in objects of worship. They incorporate multiple epistemologies, basing their programming on workshops, and promoting the democratization of curatorial power. Museums are ever more transnational. They can and must contribute to, and act as instruments of Global History. To that end, they should welcome external social and cultural interventions. Museums are assemblages of images. Their resources endow them with the energy to intervene in, and deconstruct, the interminable flow of images, and see them as more than just banalities, distractions, or entertainment. Museums are unique contact zones. It would be a regression of civilization for museologists, for fear of opening up knowledge, to lock museums away in dungeons, with the keys held by their own, closed guilds. The author is a member of ICOM