“An Island Is a World”

Homecoming

Leaving to reach Trinidad and Tobago means hearing all sorts of things and getting unsolicited advice. The stories are created by those who don’t know how to travel. What are you looking for when you visit a place? Are you curious? Do you lock yourself inside a barricade, or do you walk the streets alone, getting lost? Do you believe in stories, or do you write them?

At Piarco Airport, the arrivals hall is draped with signs that speak of homecoming. “Welcome Home”, as if being elsewhere were already part of the island’s essence: acknowledging distance, exile, the choice to migrate, only to be welcomed once again. There is a certainty here: whoever arrives will leave again, only to return.

It’s a popular belief that whoever eats the cascadura will spend their final days on the island. The cascadura is an ugly fish, with hard scales, that swims in freshwater streams and hidden waterfalls meeting the pirate coves, buried beneath dense vegetation that unravels down to the shoreline and reveals itself when the tide retreats. This fish is steeped in desire and curses, in farewells and returns, in the magic of Obeah. Here too, as in most of the Caribbean region, the law still answers to colonial priorities, criminalising any practice connected to the ancestral spirituality of enslaved Africans.

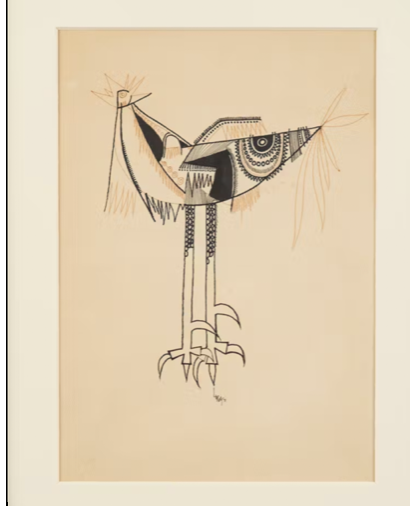

[Clarke, LeRoy, Fragments of a Spiritual. 1971, pen and felt ink on paper. The Studio Museum in Harlem]

To land in Trinidad and Tobago is to step at once into the living pulse of a diaspora. Almost a million and a half souls are scattered between two islands: one restless, alive with the blare of horns, hillside shanties, all-night delis, sticky-sweet juices, roti, corn soup and doubles, the fire of curries and spice, flavours of the East Indies mingling with African cassava. The other is an island of resorts and dreamlike beaches, reachable in three hours by ferry from the capital or a mere half-hour by air.

Those who are absent and return are most often gathered in the United Kingdom, when, after the Second World War, the Crown had sold tales of job opportunities to British citizens from the West Indies. London was the new El Dorado. Yet on arrival, they met the edges of racism, class prejudice, and the ignorance of a Britain that scarcely knew the geography of its empire. Caribbean people were made to study British history, as though belonging could be conferred by lessons in a motherland that lay an ocean away. To the British, all these migrants blurred into one: Jamaicans, nothing more. And yet the Caribbean knew Britain better - its history, its maps - than the natives themselves.

Samuel Selvon, the Trinidadian writer, recalled how in London he met his first Jamaican. He was stunned by how little the British knew about their fellow citizens overseas: “There is already in England an erroneous impression that every West Indian and everything West Indians come from Jamaica. That island is about 1000 miles from Trinidad, and the other islands lie in an arc between these two, each separated from the other not only by the sea but by complex social and religious differences”.

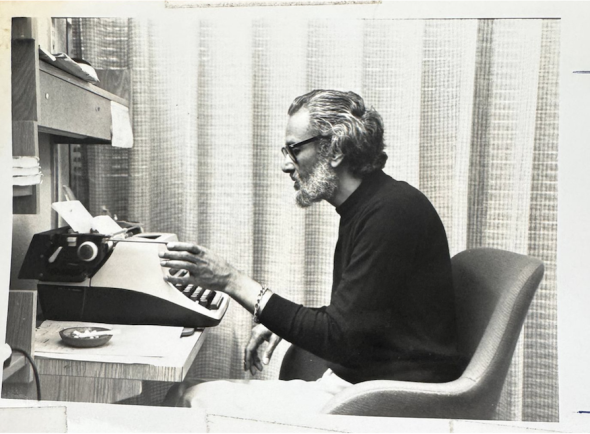

Sam Selvon, from the Sam Selvon Special Collection, West Indiana Archive, University of the West Indies St. Augustine Campus

Sam Selvon, from the Sam Selvon Special Collection, West Indiana Archive, University of the West Indies St. Augustine Campus

The language

The island of Trinidad was highly prolific in literary terms in the postwar years of the last century, and it continues to be so today. Bocas Lit Fest, the literary festival founded in 2011, which is always held during the spring, is now an established international event, discovering emerging writers every year. There is a magical realism that endures in the eyes and hands of the writers who have, by necessity, described and loved the island, whether from near or afar, through chosen migrations or forced exiles.

There has been a Trinidadian Nobel Prize winner in Literature (V. S. Naipaul, in 2001), but many others have contributed to writing and rewriting the history of the island. Often, these writers had received a lofty literary education, rooted in the absurdities of the Caribbean educational system. Anyone who wanted an education was forced to follow the English canon, obliged to study sonnets and poems that praised the snow while in the tropics. And as the Barbadian writer George Lamming said, language was a passport, a safe-conduct: thus, the creoles and dialects, forbidden in official contexts, could discredit otherwise valid job applications. People were afraid to speak their own language. They had a mother tongue that was not their own. What mattered was knowing how to use Standard British English. Think of how many migrants had to hide their origins, forcing themselves into an accent that wasn’t theirs and letting it slip only at home, sending their children to speech classes for fear they might take on patois or Creole. It’s a familiar story, and like all familiar stories, it repeats itself everywhere, in every postcolonial context.

The Barbadian academic and poet Kamau Brathwaite fought to valorise the Nation Languages, that is, the hurricane-languages of the Caribbean, which respond to the wind and the storm and cannot be confined to pentameters like standard English. Some languages have already been transcribed; others have been lost. Every island in the Caribbean tells a story of violence and erasure, and each one is different. The kaiso rhythm of enslaved people from the Kingdom of Congo, with Bantu languages mingled with drums, and with the linguistic and religious oppression of Europeans, among other forms of violence, transformed the oral expression of the islands.

Trinidad was colonised, for the most part, by the Spanish, French, and British. Its language is still alive. It is a creole. Sweet. With its rolling r. With a tongue that sings. It carries the rhythm of calypso and the steelpan; it rises and falls, it whispers, it screams, it kisses your ears.

It was the land of the Caribs and the Taino, of the enslaved people emancipated in 1834, who turned Carnival into a syncretic celebration of the daily pain endured in the sugarcane plantations, expressing themselves as kings and queens of the island guided by the drums. The European Carnival tradition here shed its ballroom dances and Catholic rhetoric, becoming pure rhythm and a hymn to life. Bodies transform into birds covered in feathers, into blue devils with horns, and the island comes to a halt to celebrate a Creole culture.

East Indians make up a significant portion of the island’s population. They arrived under the British indentured labour scheme, a macabre contrivance designed to legitimise the slavery system that lasted until the island gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. The system of “contract labourers” was common even in the old Portuguese colonies, a system created to circumvent a system that the plantation owners themselves had feigned to oppose.

The East Indians brought spices and the festival of lights. There are local political tensions between the Indian and African communities, stemming from how both groups were treated differently by the first independent governments. This reality is reflected in the polarisation of the country’s two major political parties. Trinidad, like others in the Caribbean region, has participated in regional discussions about reparations from the United Kingdom for the role of slavery and colonialism. It is still an ongoing debate, with no predictable resolution.

Port of Spain

August is when the mangoes are harvested. Displayed on rickety stalls along every side of the street, together with yellow and green coconuts, this is the fruit of the ending summer and the returning school year. You can peel them with your fingers, and they are so juicy they melt in your mouth.

I don’t have much time on the island, and I must lock myself away in the archives. Every morning, exactly at five, a Kiskadee begins to sing outside my window. In this city, there is never silence, whether from cars, music, or birds. And it welcomed me like a new memory of past lives.

Port of Spain is a world of places within a world of places, which is this nation. The microclimate, the greenery overtaking the city, and enormous passion fruits are like São Tomé. The vividly coloured stilt houses fit into the curves of the hills, like in Brazil. The best view is always for those who move away from the centre and at least remain with a handful of stars, even if they lead a simple life of bread and hardship. The trade winds blow through the restless, windy Laventille, alive with calypsonians and chaos. Belmont is where things are written. The first free people settled on this hill, making it the queen of Carnival. The gingerbread houses - looking at them makes you want to bite into the carved wood that resembles marzipan - are in Woodbrook. Saint James smells of turmeric, thyme, and chilli; Old Delhi returns in streets lined with coiled electric wires - looking up, it seems there is logic behind the tangle of cables. In Saint James, no one sleeps. The soca bass hits your stomach and calls you to drink Carib beer or rum punch. Downtown, on the other hand, is new and imposing. Skyscrapers rise over the water. Independence is celebrated, flags everywhere, red and black, like the blood and skin of the island’s people. In Queen’s Park Savannah, there are cricket matches and food trucks. This park is a green blotch among the houses, with a unique fifteen-minute rhythm: if you drive and get confused about where to stop, you have to follow the park’s boundary again, without pausing.

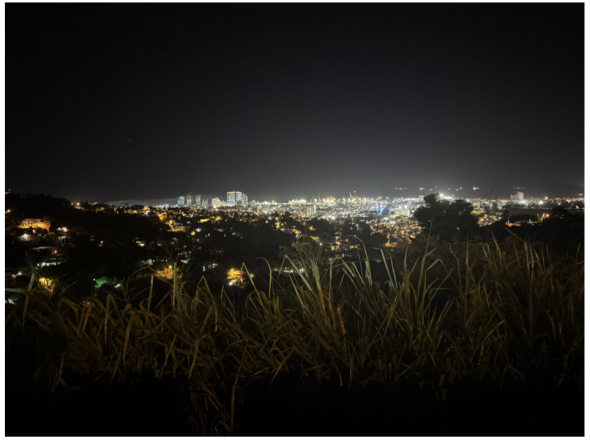

Lady Young Road Lookout

Lady Young Road Lookout

Being in Port of Spain also means getting familiar with tiny hummingbirds that buzz like bees. They are one of the island’s symbols, along with the steelpan and Carnival. Their hearts burst—it’s a drum—and they buzz like mad bees searching for fresh water. They never stay still.

The city’s outskirts are covered with old signs hand-painted on the walls of the houses. The handwriting is incredible. “Guitarist and calypsonian gives private lessons for 40TT$” – “Haircuts, eyelash application and fresh sorrel juice”. As you move away from the centre of Port of Spain, the mangrove rises along the edges of the streets, half underwater and half exposed. There are many stories about how this aquatic tree travelled from the African continent to the Caribbean region, engulfing it. A thick canopy with floating, suspended roots, weaving together tightly like arms locking at the elbows to form an armoured wall.

Mangrove in Tunapuna

Mangrove in Tunapuna

Living here means rethinking time. Appointments are never kept at the agreed hour. Street signs often point to roads with names unfamiliar to the people who live there, which is why moving around with official maps can be very difficult.

As in many places further south in the world, it is the sun that sets the rhythm of the day. Activity begins at six, with gentle dawns that soon turn scorching, and the city fills with life as long as the light lasts, only until six in the evening. Gleaming cars and cheap gasoline. Trinidad is the island of oil. You see it in the asphalt, which is even exported, in the electricity used without restraint, in the air conditioners that never stop humming. To say you feel cold at the equator is oxymoronic, yet it happens: going without a sweatshirt or scarf indoors, in restaurants, libraries, or bars, can be risky.

The heat strikes you as soon as you step outside. Heavy, humid, a sign of torrential rains about to fall. August is also the month of storms, and is when the island turns green again, as vegetation returns and swallows up the crooked houses, bent by the waters and dried out by the harmattan, which forcefully comes back from October onward, dressing the landscape in dry, brown tones.

Trinidad rises from the sea in three soft layers of mountains. Columbus gave it this name during one of his fevered expeditions, in which he declared himself saviour of lost souls in need of Catholic redemption. Trinidad, as the Holy Trinity.

Just fifteen days ago, his statue was removed from Independence Square in Port of Spain, after decades of protest. The statue has been in the city since the 19th century. Removing it means decolonising a public space, without the needless celebration of a falsified history whose hidden sides are by now well known. A statue is a symbol, a sign that carries meanings beyond decontextualised opinions. To erase from view a troubling presence, a reminder of a past that calls to be reinterpreted to be surpassed, is an assertion of fluid identities that are at last recognising themselves.

[Pos City Corporation]

Identities can be rhizomatic, woven from encounters rooted in our relations with others. Glissant reminded us that we must nurture this “something” that grows through dialogue and the alternating exchange of differences and actions.

To understand Trinidad, there can be no fixed, predetermined “root identity” in the traditional, categorical sense. The island’s culture claims its right to opacity, resisting simplification, even while its core remains Creole. Too many people, too many cultures have met - and clashed - across its ports and borders. For this reason, Trinidad cannot be singular; it is plural, maternal. Like a mother, it tells stories, at first misunderstood by its children, yet always offering a lesson. Like a mother, it lets its children wander before calling them back to the tropics.

This island is a birth of worlds.