Mere Impressions: South African Prints from the Permanent Collection, MOMA NY

Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now (March 23-August 14, 2011). Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The audacity of the printed works that have emerged from South Africa over the last century, at once expressive, formally intimate, and freighted with significance, provokes the following reflection: does the history of this medium, from its beginnings in Dürer’s solemn allegories through the poignant baroque of Rembrandt, from the satirical sketches of Hogarth, whom we may denominate the father of the comic, to Daumier’s revolutionary caricatures and especially Goya’s Disasters of War, not to mention the apex marked by the German Expressionists, whose esthetic innovations laid the groundwork for the contemporary comic—does this history not recommend printmaking as the among the most fitting means for the analysis of one’s age? Thanks to its instantaneousness, its collaborative nature, and its reproducibility, it has worked for centuries to prod the upper classes from their complacency, and it has been a perennial arm for countless artists amid the most brutal socio-historical conflicts.

General picture of the Exhibition.This notion of art as a vehicle for criticism and resistance was taken up in a programmatic manner by the South African group Resistance Art at the end of the nineteen-seventies to the end of confronting institutionalized racism in the then-totalitarian nation. A direct result of the 1976 Soweto uprising and the 1977 murder of the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko, it represented a “galvanized anti-apartheid activism” in the artistic and cultural spheres. The idea of “culture as a weapon of political struggle,” affirmed by a multiethnic convocation of artists in Botswana in 1982, appears to be the overarching theme of the MOMA’s curators in the exhibition Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now, with an eye, perhaps, to those presently fomenting global crises and the sensibilities they must produce in an audience once again attuned to injustice and inequality.

General picture of the Exhibition.This notion of art as a vehicle for criticism and resistance was taken up in a programmatic manner by the South African group Resistance Art at the end of the nineteen-seventies to the end of confronting institutionalized racism in the then-totalitarian nation. A direct result of the 1976 Soweto uprising and the 1977 murder of the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko, it represented a “galvanized anti-apartheid activism” in the artistic and cultural spheres. The idea of “culture as a weapon of political struggle,” affirmed by a multiethnic convocation of artists in Botswana in 1982, appears to be the overarching theme of the MOMA’s curators in the exhibition Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now, with an eye, perhaps, to those presently fomenting global crises and the sensibilities they must produce in an audience once again attuned to injustice and inequality.

But it is perhaps too much to attribute such an intention to an organization of the MOMA’s stamp, and it might better serve us to emphasize, first, financial considerations: a mere stroll through the Tate Modern, the Prado, or the Louvre confirms the reluctance of the major international museums to fund major exhibitions, and their growing reliance on a reorganization of their permanent holdings, which tendency is almost a policy at the MOMA; and second, the museum’s conservative wager in allying itself, institutionally, with vanguards already canonized by the culture industry and thereby avoiding unnecessary ideological and esthetic risks. The impressions of South African art from the last five decades, spread out among three ancillary galleries on the second floor, in vapid dialogue with the exhibit du jour, German Expressionism: the Graphic Impulse, and surrounded by Picasso’s guitars (Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914) and token relics of the influence of music on contemporary art (Looking at Music 3.0), among other offerings, leave the uninformed viewer adrift; without a proper guide, left to rely on a less than adequate catalogue, lacking the necessary theoretical preparation, he is incapable of extending his discourse beyond the—admittedly very striking—works themselves: fruits of a complex and tumultuous historical context that cries out to be treated of in-depth. Where is the obligatory mention of such groups as the Afropix Collective or the communitarian Gugulective, for example? Without adequate theory and analysis, without a competent exhibition guide, an enriching and correct access to these holdings is inconceivable.

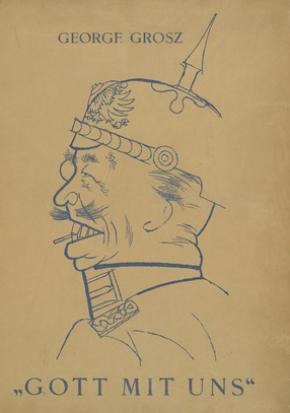

Gott mit uns, George Grosz, 1920.Yet for anyone who comes to the MOMA having done his homework, the pleasure of seeing George Grosz’s Chancellor from the series Gott mit uns (1920) alongside William Kentridge’s General (1993) is a luxury very few museums could offer, and this is capped off elegantly with Robert Hodgkins’s Sarge (2007). Likewise, the possibility of hearing Kentridge speak on the occasion of a retrospective of Dziga Vertov—the Soviet director, researcher, and promulgator of Film Truth—permits those with an interest in the former to deepen their understanding of this artist’s multifaceted production and the way in which his relation to the Western artistic and cultural traditions inform his poetics and his artistic praxis, from his engravings and theatrical collaborations to Drawings for Projection, his explicitly political series of animated shorts, which were on display in the same museum one year past, in the show William Kentridge: Five Themes.

Gott mit uns, George Grosz, 1920.Yet for anyone who comes to the MOMA having done his homework, the pleasure of seeing George Grosz’s Chancellor from the series Gott mit uns (1920) alongside William Kentridge’s General (1993) is a luxury very few museums could offer, and this is capped off elegantly with Robert Hodgkins’s Sarge (2007). Likewise, the possibility of hearing Kentridge speak on the occasion of a retrospective of Dziga Vertov—the Soviet director, researcher, and promulgator of Film Truth—permits those with an interest in the former to deepen their understanding of this artist’s multifaceted production and the way in which his relation to the Western artistic and cultural traditions inform his poetics and his artistic praxis, from his engravings and theatrical collaborations to Drawings for Projection, his explicitly political series of animated shorts, which were on display in the same museum one year past, in the show William Kentridge: Five Themes.

General, William Kentridge, 1993.

General, William Kentridge, 1993.

The exhibit’s point of departure is the artist’s collective movement that took place in South Africa during the apartheid years, supported by underground galleries, in theaters, schools, and workshops, producing magazines of an explicit social and cultural orientation, comics, and, especially, posters that encouraged agitation and solidarity in the collective struggle. These marked an occasion for reflection and for creative resistance to state oppression, producing a ferment of social and community activism that would both encourage and accompany those changes to the racial segregation laws that had been in force since 1948. The artists that composed them, of diverse backgrounds, but all politically engaged, have now passed the baton to a generation that, lacking the clear political boundaries that both defined and united their predecessors, is left to reflect on contemporary uncertainties of an at-once local and universal scope, guided by the urgency of a fractious daily reality that renders morally impermissible the vacuous estheticism so widely dispersed in the West. The exhibition comprises nearly 100 works from 1965 (when the museum purchased its first piece of South African art) to the present—among them comics, posters, wall-stencils, graffiti, and books: a brief but exemplary journey through the evolution of art as weapon—of social critique, political incitement, and personal expression.

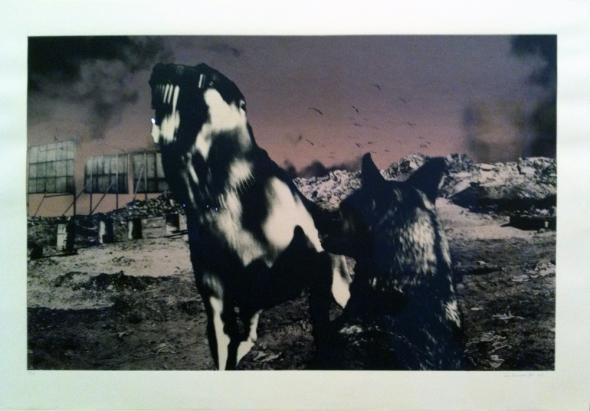

Posters of various collectives and William Kentridge, 1980’s.On entering, we first see a wall bearing Kentridge’s works, along with those of anti-government collectives active, principally in the nineteen-eighties, which invite us, unquestionably, to insurrection. These posters and pamphlets, unashamedly inflammatory, are followed by pieces by Diane Victor and Norman Catherine—arrows flung against the state terror, racism, and de facto genocide, as well as against the executioners’ implacable cruelty. Two series of lithographs depicting dystopic landscapes—Jo Ratcliffe’s Nadirs (1987) and Sue Williamson’s For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990)—speak to us of the necessary exercise of memory in the avoidance of a return to apartheid’s horrors.

Posters of various collectives and William Kentridge, 1980’s.On entering, we first see a wall bearing Kentridge’s works, along with those of anti-government collectives active, principally in the nineteen-eighties, which invite us, unquestionably, to insurrection. These posters and pamphlets, unashamedly inflammatory, are followed by pieces by Diane Victor and Norman Catherine—arrows flung against the state terror, racism, and de facto genocide, as well as against the executioners’ implacable cruelty. Two series of lithographs depicting dystopic landscapes—Jo Ratcliffe’s Nadirs (1987) and Sue Williamson’s For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990)—speak to us of the necessary exercise of memory in the avoidance of a return to apartheid’s horrors.

Nadir, Jo Ractliffe, 1987.

Nadir, Jo Ractliffe, 1987.

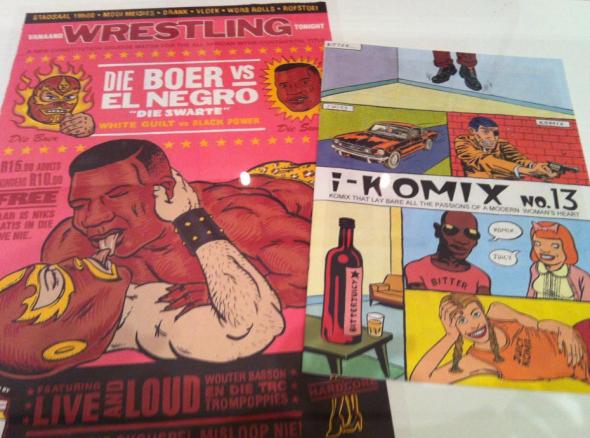

After a glance at the more popular prints by the founders of Bitterkomix, Conrad Botes and Anton Kannemeyer (later joined by Joe Dog), we see that historic covers of that publication, now a South African institution at the forefront of the “new expressionist comics movement.” As Conrad Botes affirms:

With the comics, we’re dealing with very specifically with a South African audience who knows the things we’re referring to. Originally we wrote them in Afrikaans, so many of the references are to things in Afrikaans culture. The paintings I make are much more personal.

Varius cobers of Comics by Conrad Botesm Anton Kannemeyer and Joe Dog, 1990’s.

Varius cobers of Comics by Conrad Botesm Anton Kannemeyer and Joe Dog, 1990’s.

These artists’ technical virtuosity and their capacity to adapt themselves across media, depending on the work’s message and its desired diffusion, are epitomized in the figure of Kudzenai Churi, born in Zimbabwe in 1981 but presently a resident of South Africa. He is represented in a series of three lithographs and two “outdoor murals” made with stencil and spray paint on Johannesburg’s walls during the 2008 presidential election to the end of drawing attention to the widespread corruption and to the xenophobic repression and violence Zimbabweans continue to suffer in their neighboring country to the south.

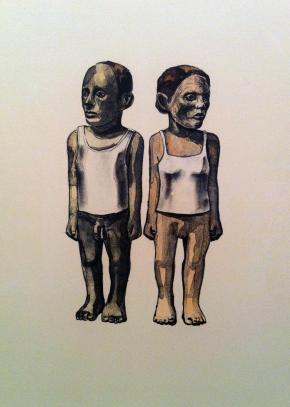

The Couple, Claudette Schreuders, 2003.The presentation of eight (from a series of nine) lithographs from Claudette Schreuders follow the same esthetic of her celebrated wood sculptures, leading us to question the relations between women and their surroundings, the stifling of dialogue in the contemporary world, and the anxiety of working out a yet-to-be-determined post-apartheid white identity. In his dialogue with the homonymous works of John Muafangejo, Life is Very Interesting and The Battle of Rorke’s Drift, we see a revision of the history of the artist and his role in contemporary life—a satirical and naïve reimagining of the national struggles of the past from the perspective of the present, in the form of an homage to the master. As the artist himself explains:

The Couple, Claudette Schreuders, 2003.The presentation of eight (from a series of nine) lithographs from Claudette Schreuders follow the same esthetic of her celebrated wood sculptures, leading us to question the relations between women and their surroundings, the stifling of dialogue in the contemporary world, and the anxiety of working out a yet-to-be-determined post-apartheid white identity. In his dialogue with the homonymous works of John Muafangejo, Life is Very Interesting and The Battle of Rorke’s Drift, we see a revision of the history of the artist and his role in contemporary life—a satirical and naïve reimagining of the national struggles of the past from the perspective of the present, in the form of an homage to the master. As the artist himself explains:

When I was growing up, I had a John Muafangejo print in my bedroom and I always looked at that… I have always been fascinated by him. He was a guy who could convey a message without portraying it, in a way.

The power of suggestion and the subversion of the figurative are well-evolved in South African art, and express its shared aims with esthetic tendencies across the broader African continent.

Finally, we are shown Senzeni Marasela’s meditations on the role of women, embodied in portraits, in several media, of her mother Theodora, and those of Sandile Goje and Trevor Makhoba, which give free reign to a revisionist nativism.

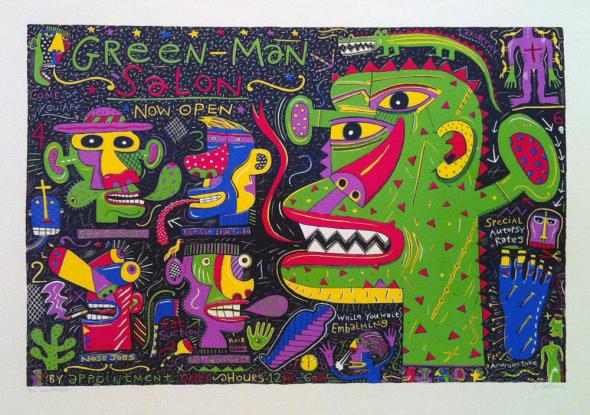

Green Man Salon, Norman Catherine, 1990.

Green Man Salon, Norman Catherine, 1990.

The present exhibit, in contrast to many others of its type, foregoes the usual recourse to ethnographic perspectives, partly out of deference to South Africa’s distinctive character and partly in recognition of the nature of printmaking: in its mechanical reproducibility, it is unquestionably modern, a privileged offspring—however often denigrated—of the twentieth century, permanently infused with the fetish for kitsch so widespread in contemporary pop culture. We may note, in this connection, how the artists gathered here cross over into the post-pop imaginary: notably in the “sugar-infantilism” of Botes and his Bitterkomix collaborators and in the cloying gaze of Schreuders, each of whom takes advantage of a neoexpressionist idiom as well as a certain grotesquerie. These tendencies are also salient in Joe Dog, Diane Victor, and William Kentridge. Many of them have recourse to the overtly denunciatory, the simplicity of their message mirrored in that of their stark lines and clear planes (Platter and Chiuri). These intellectual tendencies and formal decisions have radiated from Johannesburg and Capetown, the two major centers of production and resistance, during the past fifty years.

South Africa has taken the MOMA with the singular force of the print: its collective aspect, its technique, at once popular and rough-and-ready, its looseness and urgency, its political and historical frame of reference, its subversiveness, its revolutionary appeal, at once iconic, sarcastic, and denunciatory. The result, nevertheless, is a fragmented panorama, barely capable of adumbrating the artistic, social, and cultural upheavals that have marked this country in the past five decades. Lacking the sort of scholarly apparatus amply available for those works and movements already rubber-stamped by the Art Establishment, the academy, and their miscellaneous mandarins, these pieces languish uncomprehended: such a presentation is inexcusable in an institution of the MOMA’s stature. To this exhibit, and to the aforementioned German Expressionist retrospective, is appended a collection of posters from the 1919 Revolution in Hungary (Seeing Red: Hungarian Revolutionary Posters, 1919), to keep with the theme of celebrating “impressions.” In fact, we are left with the impression of compromise, of half-measures, of an encounter cut short with a set of truths alternately hidden, neglected, divested of their veracity, appropriated and rinsed clean of their initial revolutionary charge, left to clog up the voracious imaginary of those well-funded spaces where power and the appetite for commonplaces meet.