"We live in a world that is transforming"

Cameroonian artist Jean David Nkot’s subjects are painted against a backdrop of maps and borders, as he explored the entangled minds of migrant workers. His work has always centered around the human condition and, following a recent residency as part of the Moving Frontiers project, his work made a natural progression onto the theme of migration. He tells Alex Kahl about his own story, and how his experiences made him want to shine a light on people society often turns a blind eye to.

All images courtesy of Jack Bell Gallery.

Jean David Nkot had a normal childhood, but one that was never settled in a single place. “Because of my parents’ separation, I had to spend years, from third grade to fourth grade, with my grandparents before returning to the city,” he says. But the separation was hard on him, and his grades meant he had to retake the year. His mum soon left for Gabon, and so he spent a lot of time living with his aunts. He never studied anything artistic, even admitting that before his teenage years he knew nothing about art. “I had never even read a book before,” he says. “But art presented itself to me and I simply followed it, without knowing where the story was going to end.”

Jean began to make copies of works of art he liked in notebooks, and he soon painted first works on canvas, meeting other Cameroonian artists like Hervé Youmbi who taught him what they knew. In 2006, he joined the Institute of Artistic Training of Mbalmayo, the only secondary school in Cameroon that teaches art, and it was there that he really learned the painting techniques he uses now, and got the art history education he hadn’t had before.

These days, Jean mixes painting techniques, moving from acrylic to Indian ink, from graphics to serigraphy and from flat works to paintings packed with volume. He’s always had a keen interest in the human condition, in society and the people around him. “Those are the subjects, the themes that I nourish with readings, meetings, the exchanges with the people I know,” he says. “Society offers me to be the mirror that will allow them to get their message across. I find them in the space I share because without this society my creation has no meaning or life because it takes a dose of human sensitivity to give life to my creations.”

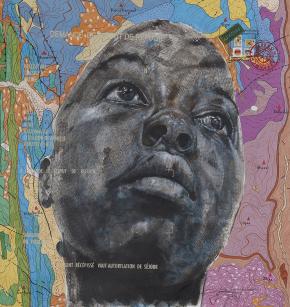

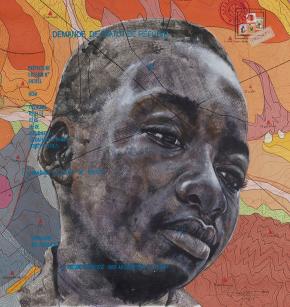

In his early works, Jean took photos of the people around him and painted close-ups of them, trying to exaggerate and express the emotions he felt in their face. All of the subjects share a similar expression, one of terror and fear. “Each face depicted in the paintings in the series does not represent one specific person, but rather the terror felt by all of the people I was painting,” he says. The place names he included in the pieces referenced the “theatres of violence” in the surrounding area.

Jean credits his mum and his aunts for his interest in people and their emotions. “I really owe them everything,” he says. “It wasn’t easy but they taught me to love, to appreciate life, to be content with what I have, and to care about others.” His work has now moved on to the topic of migration, and this seems a natural progression given his fascination with the human condition.

His interest in the topic was sparked when he became part of Moving Frontiers in 2017, an initiative organized by the National School of Arts of Paris-Cergy in France, which invited artists to explore the subject of borders. In three intensive sessions, the artists were encouraged to question their own aesthetics and invent new ones which might better explore the complicated topic, aiming to become capable of questioning our times. “The Moving Frontiers programme was important for the development of my work and it was after this project that the theme of migration took shape,” Jean says.

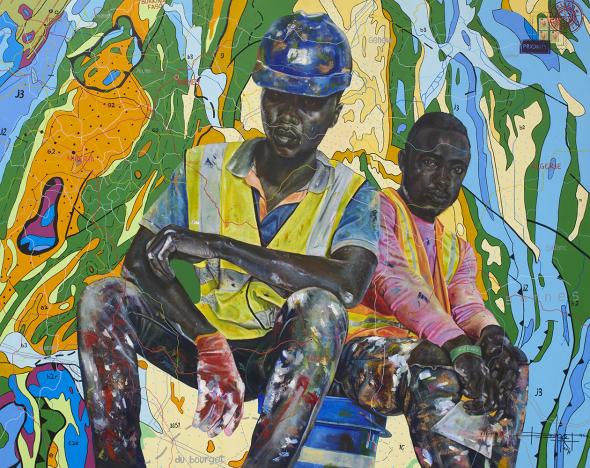

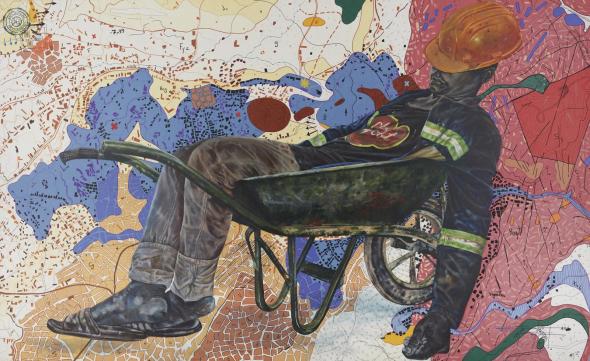

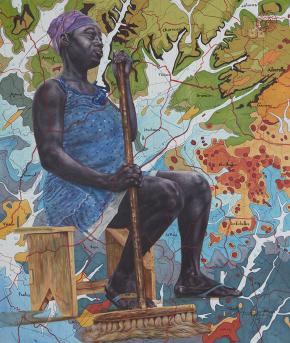

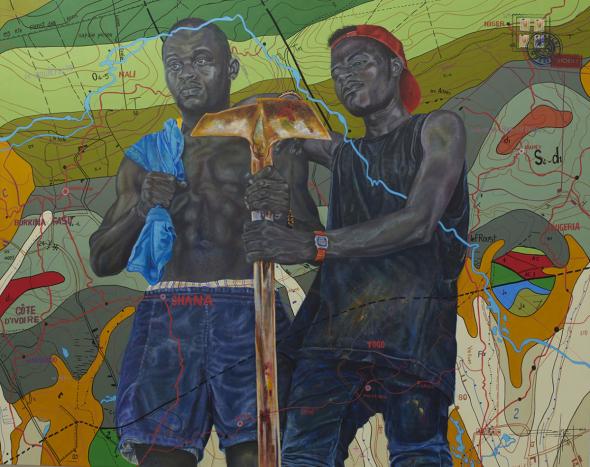

In Jean’s latest ongoing project, The Undesirables, he depicts migrant workers against a backdrop of painted maps, showing countries and the border lines between them. Some subjects hold the tools of their work, spades, pick-axes or brooms, and they sit on barrels or wooden crates. In one particularly poignant image a man sleeps in his wheelbarrow, his orange construction helmet still strapped to his head. The subjects are painted with detailed realism, light and shadows bouncing off their figures and the folds in their clothes perfectly painted. The simplicity of the half-finished maps behind the workers makes the background and the foreground of each work appear separate. Often the border lines on the map overlay the bodies of the subjects, though, emphasizing the fact that the anxiety caused by these borders weighs heavy on their minds.

“The maps in the background allow me to represent the many places that jostle in the head of a migrant,” Jean says. “And in the foreground we have a figure, a human form that observes us, that questions us about the state of the world and invites us to a form of reflection.” As he painted, Jean thought back to chats had with friends who left their families looking for adventure. Friends who have failed multiple times to cross borders, yet still “stubbornly defy the barbed wire,” trying and trying again.

Jean’s aim is to give these people and their frustrations a voice, and to make the viewer confront their own perspectives on migration. “I think a lot about the indifference that characterizes the complicit silence of the rest of the world towards victim states,” he says. “I’m inviting an awareness necessary to free the world from these dehumanizing practices.”

When Jean says these questions of the human condition are naturally important to him, it’s largely because of his own experiences as a teenager. “I began to think about the violence I suffered psychologically and physically. I made myself vulnerable to those past experiences and this really allowed me to make a transition to better advance in my work,” he says. “My own condition as a child has been an important source of inspiration for my artistic adventure.”

Jean often says that he’s a person before being an artist, and his sense of empathy is an important part of his work. His series on migrant workers is simply a continuation of his mission to look at the people affected most as society continues to evolve. “We’re living in a world that is transforming, and that transformation speaks to me and concerns me.”

Article originally published by WePresent