Ricardo Farinha – Hip-Hop Tuga, a Portuguese cultural phenomenon

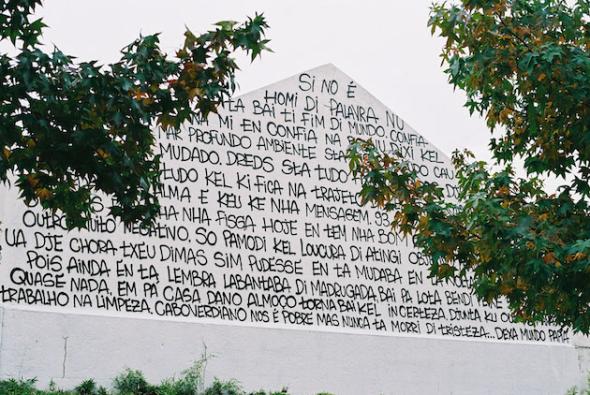

Hip-Hop is a marginalized music, both in its origins in the USA, and again when it arrived in Portugal and eventually became Hip Hop Tuga, as in the title of the first of Ricardo’s books, now in its Second Edition (2025), after only two years. Being a marginalized artform it showed the symptoms of cultural insecurity, but as it grew in confidence the artists dropped the use of English inherited from the US, replacing it with Portuguese, and with Cabo-Verdean Crioulo reflecting the influence of this community, all over Portugal but especially on the opposite side of the river from Lisbon, the Margem Sul. The cultural insecurity also affected the artists themselves, who were often getting burned by a music business inhabited by piranas, as the story of Djoek, the first person to release a rap album in Crioulo shows. His career was marked by gaps following episodes of disillusion before returning to receive the appreciation he deserved after the release of Amigrimi.

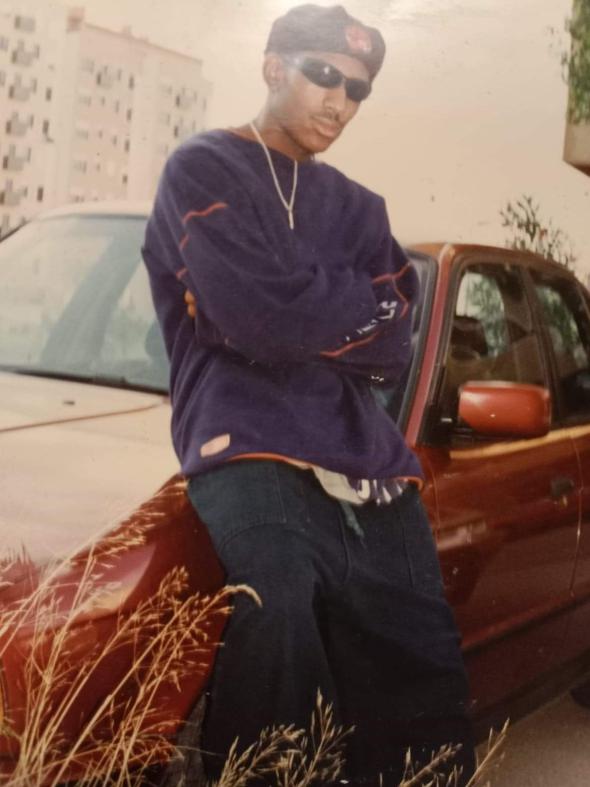

Djoek, cedida a partir do livro 'Hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

Djoek, cedida a partir do livro 'Hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

A feature of Hip-Hop is how eclectic it is, and how its artists gained confidence to move fluidly between a variety of styles, including Afrobeat, Funaná, Kizomba, incorporating jazz instruments. Yet Hip-Hop is also very tied to local roots: in Porto it was much influenced by the white group Mind da Gap, whose music is more romantic and influenced by rock than by the street culture of Miratejo. And Trap music in the southern states of the US has this strong regional character and rivalry with northern Hip-Hop.

Hip-Hop in the margem sul developed out of youth culture, where skate-boarding and graffiti artistry provided meeting places to listen to music.

A fruitful collaboration between Ricardo, the filmmaker Luís Almeida, and the music critic Rui Miguel Abreu led to Ricardo’s book of interviews, Filhos do Meio, an exhibition on the history of Hip-Hop in Almada for six months at the AlmadaTown Hall, earlier this year, and then to the documentary film itself of the same title, which was shown at the IndieLisboa film festival this year, to a wild audience response.

An interesting counterpoint to Hip-Hop is provided by the project Batoto-Yetu, which works with younger children than teenagers, from socially deprived areas of Greater Lisbon, and also originated in the US. But it was not a social movement, involving the identity concerns of teenagers and immigrant communities that were central to Hip-Hop Tuga.

Dr. José Machado Pais of the Instituto de Ciências Sociais (ICS) in Lisbon, kindly provided me with this summary:

The association was established in Portugal in 1996, but the project began in 1990, in Harlem, New York, under the impulse of Júlio Leitão, an Angolan choreographer who immigrated to the United States, and he spread the project to Brazil and Angola. Batoto-Yetu’s dances are predominantly Angolan and Cape Verdean. Júlio Leitão has a very interesting trajectory; the project was implemented in Portugal with the support of the Luso-American Foundation for Development (FLAD).

Portugal has a rich multicultural heritage in music, and one connection can lead to many others.

Following the IndieLisboa festival, I spoke to Ricardo for Latinolife, and here he speaks more about his book, which is far more than the ‘book of the film’, for Buala.

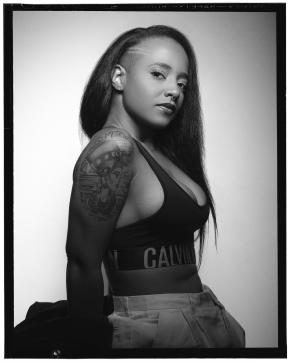

Cedida a partir do livro 'Hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

Cedida a partir do livro 'Hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal' Cedida a partir do livro 'hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

Cedida a partir do livro 'hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

Your book came before the film, and Daniel Freitas invited Luís to make the film.

I grew up here in Queluz an area with a great African influence, which is connected here in Portugal, very strongly, with Hip-Hop. I was born in 1995, so when I was in school, there were already known rappers in Portugal, and rappers playing in the radio, so my interest comes very naturally as a listener, and I always was good at writing and studied journalism at university. My personal interest was very much culture, art and especially music, and inside music it was rap which was becoming quite big in Portugal at the time I left university in 2016, but there weren’t many people writing about it. I began to write blogs about Rap, to spread the word about new projects coming out, I became a professional and I understood that there were a lot of stories that weren’t really told, that got lost through the passing years. My book came about because I wanted something broader than academic theses, that were very focused on a certain era or a certain place and with a lot of sociological analysis.

The second edition came out this year only 2 years later, you are doing pretty well.

It was a success for the Portuguese market, and both the publisher and I were quite surprised, and that led me to this project with Luís and Daniel which is Filhos do Meio.

I was working as a journalist for New in Town and doing the book in my spare time.

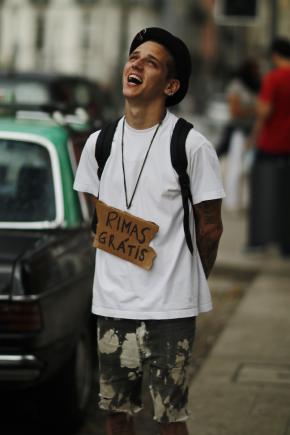

When the book came out, by coincidence I became a freelancer and I started writing for several outlets here in Portugal Jornal Observador, Público and Blitz, and Rimas e Batidas, a digital magazine focused on hip hop and urban sounds, edited by Rui Miguel Abreu.

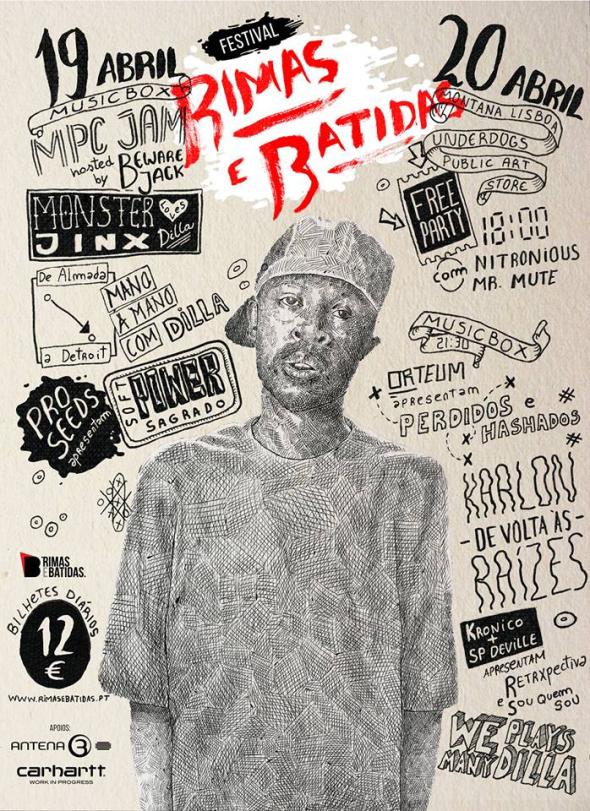

cartaz rimas e batidas

cartaz rimas e batidas

And it’s with Rui that this project begins

Rui is a journalist a music critic, a radio person for many years and he was one of the first people to do that in Portugal, he began his career in 1989 specialises in black music, writing about jazz, hip hop, funk. He also worked at music labels, and because of that he was invited in 2023 by Almada’s city council museum team to organize an exhibition on Hip-Hop, which ran for 6 months until April this year.

That exhibition was quite important

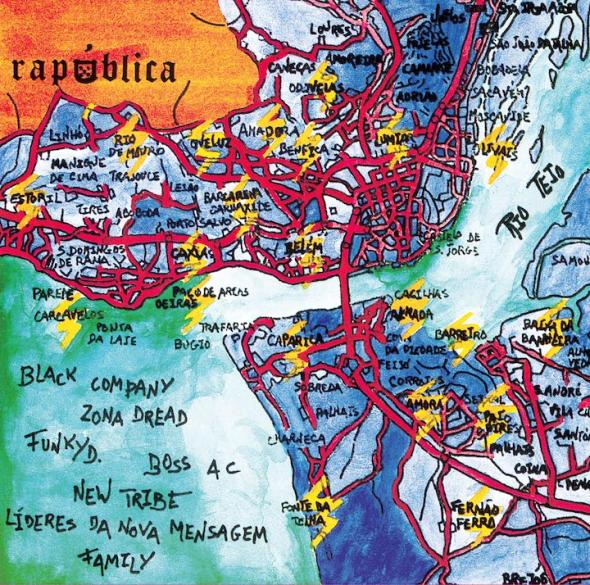

It was, because the album Rapública was celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2024, and Rui called me to join the project along with Daniel Freitas and Daniel’s brother Francisco. The four of us were the main organisers of all the projects but then we thought we could do a documentary and a book, so we invited Luís to do the documentary. My book Filhos do Meio, which is about the theme of the exhibition that goes beyond what was shown in Almada. The book, the film and the exhibition complemented each other.

It’s about a larger area than just the city of Almada, from Miratejo to Costa da Caparica. Miratejo is very famous in hip hop culture in Portugal, it’s often compared to the Bronx of New York, the birthplace of hip hop in America. I don’t think that’s quite accurate because hip hop was an American culture that was beginning to influence people in Portugal, not only in Miratejo.

Your book uses the word ‘Tuga’, isn’t that a bit pejorative? Or was it like Gays deciding to adopt the word ‘Queer’ or Hippies to call themselves ‘Freaks’?

I’ve written a piece about the name Hip Hop Tuga, and what I found out was that Portuguese speakers who were not Portuguese, referred to the Portuguese as ‘Tugas’. It was neither pejorative nor complimentary, but people began to use it to call themselves Tuga. It started in Lisbon and spread. Nowadays it’s very common, not only among Hip Hop people. There were big events in the Meu Arena called the story of Hip Hop Tuga, and now you see it on Spotify playlists to refer to Portuguese Hip Hop. It’s really rooted in the Hip-Hop community and it’s a way of saying that Tuga Hip-Hop is special, different from the other kinds, so it was the right title for the book.

The film shows that Cape Verdean influence is very strong, and Miratejo has a strong CV community, so did Hip-Hop start there?

In the mid 80’s small groups of people began listening to American Rap and dancing the breakdance, which was a fever here in Portugal and across Europe in general where it was a trend that eventually faded away. But some people really connected with Hip Hop culture which includes Breakdance and graffiti and Rap music, in Porto, the Algarve and the Lisbon area, including Miratejo. The first rappers began to rap and to rhyme and to do shows, record amateur demo tapes at home. Almada became a meeting point for people in Lisbon that were interested in Hip Hop culture in the late 80’s, beginning of the 90’s. Because it was such a niche culture at the time, but it was a community that was being born, and Miratejo became known as the Bronx of Portugal, but at the same time people were doing things Hip Hop-related In Porto, in the Algarve, so Miratejo wasn’t the only source, But Lisbon being the capital, and with the biggest African communities was very important. And then in 1994 the album Rapública was launched and things spread further.

Cape-Verdeans developed hip hop in Almada, other areas are more Angolan, do they have their own varieties? Or have they just kind of followed into the one that’s kind of really got the crowd behind it?

I think it was really a mixture from the beginning but black teenagers from all the African ex-colonies, marginalised people, recognised themselves in the lyrics of American groups that talked about racism and social injustice, which they experienced in the US.

But since the beginning, white kids that were in school with these black communities liked the music, the attitude, the aesthetic and began to rap. So, it was a mixture from the beginning. General D, the first rapper to release an album in Portugal has Mozambican origins, for example. Nelson Neves, who is an important person in the film, was the one who brought the music from Paris because he spent vacations there, and he’s the son of Cape Verdean parents. In Rapública you have white artists like Líderes de Nova Mensagem, which was a band that had black and white musicians, rappers and DJs, and they’re from Almada.

They were doing rap because they were very much the product of a suburban environment. Being from Cape Verdean parents Or Mozambican or Angolan or Guinean, this first generation of people in Portugal recognised themselves in hip hop culture, and the social tensions here had a major importance, because many of these young people formed groups in hip hop almost as a reaction to skinhead movements. This is important to understand why hip hop makes sense in Portugal. An American, not knowing very much of Portugal might find it hard to understand, but it’s because of all these tensions happening in these urban and suburban areas.

Miratejo was a new neighbourhood with social housing, and in the 80s it was like a fresh neighbourhood with people from Cape Verde, Angola and poor Portuguese people, it was something new, and I think that’s one of the reasons that made Miratejo important in this story because people from different cultures were mingling and their sons and daughters were the first Rappers in Portugal.

The name that comes up to me in relation to police repression is Cova de Moura on the north bank, but that doesn’t seem to figure in the story of rap. Is that because, the Cape Verdean development was more influential?

Cova da Moura is important in the Portuguese rap history as well, but as far as I know there’s no records of people doing rap there in the late 80s and early 90s. The first artist that I know is from Cova da Moura, the oldest one, is important because he was the first rapper In Portugal to release an album in Cape Verdean Creole. His name is Djoek, and he released an album in ‘96, which is very early, it was only two years after Rapública. I’m sure he was the first artist from Cova da Moura to release a record or to make something more professional in rap, and maybe the first to do something related to Hip-Hop culture. He had a home studio and recorded friends from Cova da Moura and other places, and he’s from Cape Verde, and came here as a teenager. Cova da Moura is obviously important but Hip-Hop in Portugal was born in other places before that. Maybe the people in Miratejo although they were poor, had better conditions for making music.

The police repression in Cova da Moura has been really brutal.

It’s like a self-built neighbourhood, often without planning permission, and that makes all the difference in the way the police or the state operate. Cova da Moura was a ghetto, a closed community from the very beginning, that through the years became legal, which is different from a social housing neighbourhood that the government builds for poor people.

That’s an important point

But going back to Rapública in 1994, the first year that records were released in Portugal, had people rhyming in Creole side by side with Portuguese, and Portuguese people rhyming in English: that record has everything! There were no English rappers, but they were rhyming in English inspired by their American rivals.

Glaucia Nogueira has studied the way that Cape Verdean music culture has drawn from rhythms of 19th century European dances, and after independence, they didn’t reject it all and say, well this is not us, they incorporated it. Did that cultural openness help Rap and Hip Hop to develop in the Cape Verdean culture? Perhaps it’s because Cape Verde is a group of islands and all the other ex-colonies are on the African mainland?

Obviously, Cape Verde has a very fluid culture, because it has all those influences, and it’s a country born out of colonialism and the mixture of people that were slaves brought from Continental Africa and the Europeans that were there.

Cape Verde is fascinating because the story is unique, but I don’t know if I find similarities between that and Hip Hop in Portugal. There were Cape Verdeans in the beginning and throughout the evolution of Hip Hop in Portugal, and it’s a culture that influenced Portuguese Hip Hop specifically because the language of Creole is very much used. You have white Portuguese rappers rhyming, writing in Creole, because they were born or grew up in communities with a big Cape Verdean influence. And for a very long time, for the first 25 or 30 years of Portuguese Hip Hop the standards were very American, the reference, the idols, what was considered to be good.

There were even a lot of African descent people, not just Cape Verdeans, who were rappers that were very purist regarding Hip Hop and Rap, and they didn’t want to mix that with their traditional culture of Kizomba or Funaná or whatever. They even associated that traditional culture with their parents or their grandparents’ culture so it was not cool, like maybe young white Portuguese could see Fado as not modern. Even now with a new generation of people singing Fado we see it as a traditional old thing, and many people with African descent also saw their traditional music like that. People who were very into Hip Hop culture neglected or put aside that part of their life and culture and personal story, the reference was really American Hip Hop.

So, except for the language of Creole there were not a lot of mixtures between those worlds. It was a bad thing to mix, and you still had Rappers with Angolan or Cape Verdean or São Tomense parents or grandparents that even in the lyrics they talked bad about those kinds of music and traditions regarding Hip Hop. The standard was very American.

Skateboarders - It’s a very young culture, so is it fair to say that a big part of what they were doing was a teenage rebellion?

Sure, that was precisely it, and it’s not a new thing, the Nelson Neves generation who are now in their ‘50s already had that perspective. They were born or grew up in Portugal, so their references were not Morna or Funaná which was their parents’ music. Hip Hop was so important to them because it was talking about the things that they felt. It was a young, fresh music and culture which reflected the black experience in America, but it had so many resonances here in Portugal. They were rejecting their parents’ culture, and they didn’t have a great connection with the Portuguese traditional culture either.

Luís talked about the Mafia Suliana, imitating the US Mafia structure, and yet they consider themselves to be purists, here in Almada: ‘We’re not doing this for commercial reasons, we’re doing this because it’s us, our identity’. The concept of identity seems very relative and very fluid: you might have considered yourself once upon a time to be pure Cape Verdean, but now you’re pure and authentic because of something from a different country.

Exactly: even though it’s not pure

In the first years of Hip Hop records in Portugal from ‘94 to ‘96 or ‘97 The only way to release an album was with a big label. But then this big underground movement that hadn’t had that opportunity began doing mixtapes, creating a movement that was very anti-system and anti-music industry. It was very marginalised and self-marginalised as well, and they talked about that a lot in the music they made. Mafia Suliana matches the beginning of that mentality of the ‘we are on our own, we do things for ourselves’ spirit, even rejecting the music industry.

Until the early 2010s that was the standard of Portuguese Hip Hop culture that was the mentality of rap as separate, there was no rap in festivals and hardly any on radio. And then things began to change. The underground authenticity was not a commercial thing, it was something really deep and rooted, to do with the values and the references of New York rap of the 90s.

a partir do livro 'Hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

a partir do livro 'Hip Hop Tuga - Quatro Décadas de Rap em Portugal'

In the Caribbean there is a polarisation between the people who consider themselves to be ‘strictly roots’ musicians, ‘this is my music, this is me’, and the ones who take from all sorts, I think they actually talk about a creolization of the music. It’s very sociological.

Exactly, and I like very much that sociological aspect of these movements, which are musical, but they are a lot more cultural and social, that’s very interesting to explore.

Fado was originally a marginal culture but then it became quite conservative. The way they reacted against Fado Bicha for example. Now Fado is a symbol of Portugal for tourists to consume, a music business, and the people who were once marginalised are now excluding other people on the basis of their sexuality.

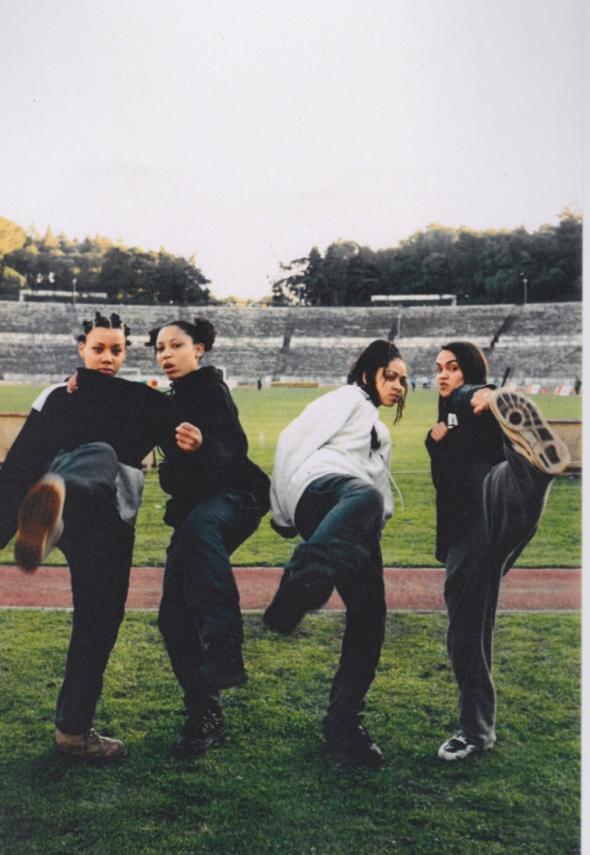

In the film, Juana na Rap and Shiva were talking about the situation of women in a relatively male environment. Could you say more about that? The lyrics of US rap are often really misogynistic, referring to women as ‘bitches’.

The big standard specifically in Hip hop in Portugal was mainly the New York Rap from the ‘90s, which was more about, having the best skills as a rapper and it was more socially conscious and more anti-system. But Portugal has its own culture of misogyny, that’s very rooted here and is not related to Hip hop at all. So, between the two influences it was always more difficult for a woman, hip hop and rap are really very masculine, it’s portrayed as something virile to do.

The figure of a rapper is very powerful, very confident, a big ego all of those characteristics most associated with men. Portuguese society in the ‘90s for example or in the early 2000s 30 years 40 years after the revolution wasn’t ready for women with the hip hop attitude that is almost required to be a rapper. Today the country Is more open and prepared to have women rapping but many of those challenges are still there

One of the African bars in Queluz, closed now, used to show video clips that involved sexy women draped over the bonnets of expensive cars with the driver wearing bling and tattoos. But this is not especially rap, would you say it’s less common in rap now?

In the last 10-15 years things changed completely, the old school rapper still exists in some underground scenes, but the standard today is to talk about the hustler life that was almost forbidden before. From the beginning of the 2010s When Trap music blew up and became a big thing here in Portugal.

Can you talk about Trap music?

It’s a genre of rap that began 20 years ago in the southern US, and Atlanta became the capital of Trap music. It was about the lives of those people from poor neighbourhoods who deal drugs and had criminal lifestyles, and they began to reflect those kinds of experiences in their music. It was a more electronic Rap, the beats were faster, and it was also more melodic. In the ‘90s it wasn’t thought good to see a rapper perform the chorus, the more melodic parts. Trap changed it all because with tools like the autotune, the difference between singing and rapping became less distinct. Back then it was really separate: “I rap, you sing”. It was already happening, but trap music destroyed that standard, and it changed the lyrics that were typical in the ‘90s. Trap words are about doing what it takes to rise in life, to get the money.

You can look at it through a political perspective, people who turn to crime to escape poverty is the very essence of trap music in the States, and it influences hip hop throughout the world. Around 2015 the new generation of artists in Portugal began to shift to this more trappy music, and the older rappers stayed in some kind of limbo, they began to use updated beats but talked about the same subjects as before. The standard of the pure rapper simply died. Glorification of money, and hustle to have the big expensive car is the mainstream rap here now. And along with it comes the misogynistic attitudes, less socially conscious, the big car and women treated like trophies, proof of your success.

The traditional type of macho culture in Portugal is less evident, society is more progressive, which goes against the rap macho culture.

The two kinds of rebellion, “I don’t see myself being represented by these mainstream politics, so I want community politics”; and then there’s these other people who want to pay less taxes, “the state is stealing my money” attitude.

Hip hop in Portugal was very left wing in that sense and nowadays it’s not plain right wing but it’s more neo-liberal in the sense of economics, more right-wing in being about money and individualism.

Sometimes I’m very shocked by things that hip hop people are saying. It’s a black origin community from marginalised areas, but there are people from that community, old schoolers or new schoolers that have that Trump populist right wing mentality, even against immigrants. For me that’s completely the opposite of what hip hop stands for, which is very anti-system it’s the traditional war between social classes. But you hear things that are not educated attitudes.

It’s not only a hip hop thing It’s happening throughout the world. Here in Portugal the old communist districts are now voting Chega, the far -right populist party. I just hoped that hip hop was more Immune to that because it’s a black origin migrant progressive culture. But it’s not immune, unfortunately.

It would be hard to imagine rap music being played at a Chega rally

Five years ago, it would have been a lot stranger, but I wouldn’t be that shocked now if certain people did that.

I guess this situation this has produced some conflict within Hip-Hop culture.

Yeah, it’s not yet an open conflict because I think there’s still shame for people expressing far-right attitudes inside hip hop culture, compared to other places in society, but it’s an important issue. We have still a very strong left-wing faction in hip hop in Portugal of several generations of several kinds of music inside rap, and we have people that are thoughtlessly sharing far-right publications or even conveying far-right messages in their songs, not explicitly but you can feel that the prejudices are there.

Can you talk about the connection with fashion?

Hip hop Is a young urban culture and fashion is very important as it was in the 80s. The kind of things that attracted the Nelson generation, the Fade hairstyles, big necklaces -

We call it bling in English –

The baggy jeans and outfits in the 2000s, suddenly became old-fashioned, and then it came back because fashion is very cyclic. The ‘80s and ‘90s were before my time but the youth culture was very divided between tribes: the punk rockers, the goths, the metalheads, and you had the hip hop people. Teenagers now have a different experience to mine from that kind of tribe experience because I think we were the product of the mixture of different cultures, the globalisation. A lot of my friends listened to rap as teenagers, but they also listened to rock and to pop music. That mixture reflected in the way they dressed or what they paid attention to. Skateboarding culture was very much present and even surfing, so those kinds of brands were the standard. Nowadays, it’s the Sports brands, the Nikes, Adidas and Pumas which have a big connection with Hip-Hop and youth culture in general because Hip-Hop was associated from the beginning with youth and sports, that very Informal lifestyle. Fashion Is still very important but it’s not so compartmentalised.

Since the 2010s it’s become much more open, a mixture of things and kids today don’t Identify themselves as a specific group, and this connects with the more individualistic, less collective society everywhere. Fashion was like the lyric that someone sang or the poster they had on their wall. Fashion was an element of identity sure and still is of course. People who are now in their ‘40s say that in school they immediately knew who was into hip hop and who wasn’t by the way people dressed. Now Hip-Hop is so mainstream that almost everyone listens to someone from rap.

Is it more about labels now – wearing expensive labels shows you are successful?

In the ‘80s and the ‘90s brands were important as well because there were certain labels that were associated with different sub-cultures Fred Perry with the skinheads, and the punks or hip hop had their labels. The Adidas and the Nike and the Nelson Neve generation used to steal the Mercedes and Volkswagen symbols from cars to put on their necklaces because they saw their idols, their favourite American rappers using that necklace.

The importance of brands didn’t change much we just have different kinds of relationships with them. Back then people looked at each other like part of a group and now it’s more about the individual, that’s the biggest difference. Fashion is still part of the identity of the person or their social group. Punk rock became known for the Mohawk, and hip hop had its own symbols for you to be perceived as cool. You had a lot of streetwear brands that were associated with hip hop and then it mixes with the skateboarding culture. There were streetwear stores in Lisbon that were meeting points for the hip hop communities, and those shops were the first places to sell graffiti cans and rap CDs In Portugal.

project Filhos do Meio.

project Filhos do Meio. project Filhos do Meio.

project Filhos do Meio. project Filhos do Meio.

project Filhos do Meio.