"It's not just his music, it's also the way he uses stories", Catarina Alves Costa about Orlando Pantera

Orlando Pantera was a Cape Verdean musician, who died in 2001 at the age of 33, without recording any albums of his own. He was someone always behind the scenes, but on the rise when, a week before the recording of his first album, he died. This film rescues him from anonymity, through a creative use of sound and image archives shot by the filmmaker in 2000 and collected by Pantera’s daughter, Darlene Pantera, now at the age of 30, over several years. A cinematographic and poetic film, a sound journey to meet the places, voices and figures that revive his music. The film is enriched by contemporary musical interpretations of Pantera’s music, by artists like Mayra Andrade, Princezito, and many more. The story of how a musician’s influence echoes across generations.

Catarina has been making ethnographic films as part of research projects, for museums and about communities in Portugal: creative documentaries. She teaches visual anthropology at Nova University in Lisbon, and her students make films. Several of her films have been shown at the Indielisboa Film Festival, and Doc Lisboa.

Mayra Andrade, still do filme

Mayra Andrade, still do filme

She has made two previous films: in Cabo Verde, O Arquitecto e a Cidade Velha (The Architect and the Old Village) about a UNESCO site that was being preserved by Alvaro Siza, a Portuguese architect. And Mais Alma, about artistic life on Sao Vicente in Cabo Verde.

In Portugal she made other films, including Senhora Aparecida, about tensions between tradition and modernity in a Portuguese village

She doesn’t call herself an ethnomusicologist: “this is just a film about music”, she says.

I spoke to Catarina for Buala after her film was shown at the Indielisboa film festival this month.

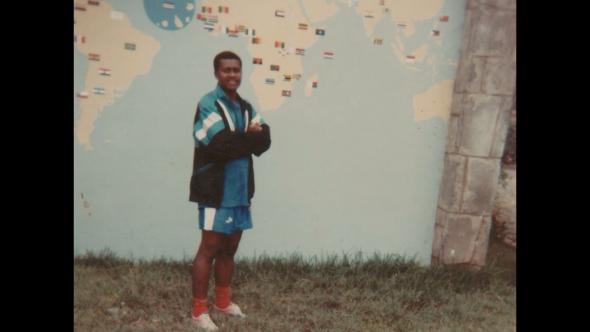

Orlando Pantera, realizado por Catarina Alves Costa. fotografia do programa Bem-Vindos, RTP África.How did you get interested in making a film about Orlando?

Orlando Pantera, realizado por Catarina Alves Costa. fotografia do programa Bem-Vindos, RTP África.How did you get interested in making a film about Orlando?

A lot of the footage was shot by me in the year 2000, when I went to Cabo Verde, a year before Pantera died. I was there to research a film, Mais Alma, about artists and performers that use dance, music, young people searching for ways to do their creative work in Cabo Verde. During the shooting of this film, we found Pantera, and I was very touched by his music and his work and so I used some of this material in this previous film. But I kept the rushes that we’d filmed, and it was Pantera’s idea that we recorded his music because he wanted to have some good quality recording, so that was luck that we got that: 24 years later I started working on this material. I had the impression then that there was something very particular in the way he was working with all the traditional rhythms and doing his own research. And I was impressed by the guitar, the tone, and the emotions involved.

Why did it take so long to make the film?

Because it was a very big shock when he died, aged 33. He was in the film we were making; he was going to come to Lisbon to make his first record, and then suddenly he died unexpectedly. I didn’t know what to do with this material, it felt awkward to make a film with it. A few years ago, his daughter, Darlene, who was six when he died, came to talk to me and said we should make a film about her father, and that she had lots of material. I went to Cape Verde, did research there and found some more archives. The process of financing and making a film, writing a project, finding the people, takes a long time. And so does the process of mourning, I needed that time.

Orlando Pantera

Orlando Pantera

Is African or Cabo-Verdean music an interest of yours?

Not in itself, but I got interested in Pantera’s story and music, also because he was a person who does research for his music. He would go to the tabancas, fiestas, rituals, the traditional batukus, collecting all these traditions, mostly Afro sounds and Afro ways in a country that is always searching for its own identity, Cabo Verde, and bringing that into his own music.

His process was like the one I use in my films. But, of course, I also think his music is quite special, and he was a very special person. He was very generous, doing a lot of social work, working with street children. He was very engaged in working for a society in the ‘90s that was starting to develop its own independence, since it was formally declared in 1974. It’s not just his music, it’s also the way he uses stories about the people that live in Santiago, in the interior and rural areas of the island.

In the public mind in Europe, Cape-Verdean music was Morna, thanks to Cesaria Evora. But Funana and Batuku are styles of music that were looked down upon by the colonial authorities, and Batuku is a big part of what Orlando does. Did he join a process of rehabilitation that was already happening, or was he a major force in that?

He was a major force in that. The anthropologist, Rui Cidra, has written about the history of music in Cape Verde, including Pantera.

Pantera was a very important person in bringing Batuku tones and rhythms to the guitar and acoustic music: as someone in the film says, “he puts Batuku on the family table”. He also brought Batuku to the élites. Batuku was a tradition of the women getting together to play, tell stories and dance, but it was not taken seriously by the élite. That comes with independence, with Cape Verde having to find its own roots, and the influence of the slaves that were taken to Cape Verde bringing their own rhythms, their own music. From this mixture, Cape Verde developed its identity, including of course, Morna, which is still there. Pantera wrote a Morna called Dispedida that is sung by Mayra Andrade in my film, recalling the different styles that are part of this rediscovery.

But he was much more interested in the Afro rhythms of Cape Verde, and he was a very important person in bringing this to contemporary music. You can see this with young and not-so-young people like Dino Santiago, who is working with Santiago Island rhythms, and a lot of the young rap people are very fond of taking these roots and transforming them into a contemporary beat.

Bringing Batuku, a village kind of music to a wider acceptance was quite a transition?

He was living in the village, but then he went to the city as a teenager, and there was a lot of Batuku in the city of Praia. I think his relationship with the city was developed when he was working with the children in Assomada, a small city near Praia. But he didn’t start to do his own shows and concerts until 2000. He was writing music for others.

He had no fantasy of being a star. He’s someone that took time to find his style, his own proper style, his own music. And this is very striking in the film and in his life. We can see from the material that we have that he was rehearsing a lot at home, playing his guitar. And then, he died. He didn’t have the time to live as an artist. And that’s also why I thought I should make this film, because otherwise people know his music, but they don’t know it’s his. If you sit in a Cape Verde restaurant or a bar and people are playing music a lot of it will be Pantera’s music, but they don’t really know whose it is. They think it’s traditional music from the country, so for me and Darlene it was very important to show that it’s composed by him. He made the jump from the traditional roots to the guitar and to the more modern, contemporary beats of the music.

Darlene Pantera, still do filme

Darlene Pantera, still do filme

He changed some of the chords that he would play, and that’s what B.leza did in his music. Is there any connection?

He knew the composers from the music of Cape Verde, but he also knows jazz. We have his personal tapes, and it was interesting to see what he was listening to, a lot of Brazilian musicians and a lot of jazz. And traditional Afro music. And he said that because he was brought up in Angola, he absorbed those rhythms.

And the way people gather to sing, and play is very important for the culture of Cape Verde. It’s a very strong way to socialise and even to dialogue between themselves. That’s also why I wanted to bring to the film these moments of playing together and this music is improvised, what we call there the “tocatinas”. I think this is the way Pantera learned to sing, not by imitating, but by getting to the old composers of Cape Verde and singing along the same songs. And he wanted to mix all this up in the present moment.

When the film started, it blew me away that you see this woman dressed in red. With such a powerful voice and movements. And then all the women drumming in a semicircle, but so powerful.

Batuku is completely female. It’s a womens’ gathering. There is a very strong woman bonding in Cape Verde because a lot of the men emigrate. And this is a traditional way they tell stories, with a lot of improvising. And Pantera was very interested in how women represent music.

He was interested in the traditional sounds, and in showing how people lived in these rural areas. A lot of feminine ways of singing and being together are present in Pantera’s music. He does some vocalising, like when he sings Play away, play away, about women that get a lover because the husband has gone away. The way he sings this, I think is inside his head, he’s trying to bring to the music the strong character of these Cape Verdean women. He’s far away from a typical man’s approach to music.

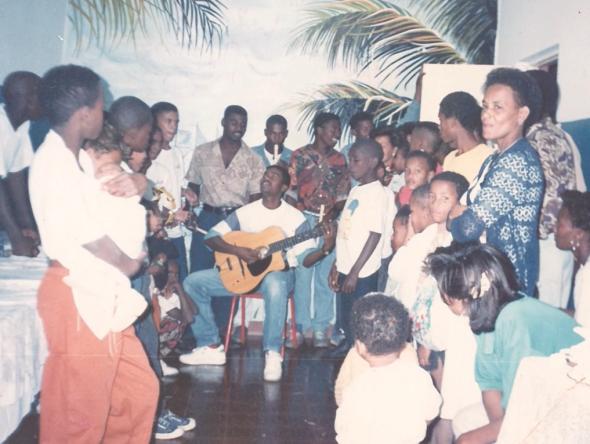

Arquivo Fundação Orlando Pantera

Arquivo Fundação Orlando Pantera  Arquivo Fundação Orlando Pantera

Arquivo Fundação Orlando Pantera

But there were scenes where he and a couple of other musicians are playing guitar and singing.

He was not singing along with the Batuku. He was just bringing these rhythms into his music. One of his main songs is called “Batuku está na moda”, meaning ‘Batuku is the fashion’, the lyrics of the song are saying ‘now it’s the time for Batuku’, and the rhythm is Batuku. Princezito, one of the musicians who talks in the film, explains the rhythm of Batuku and how he brought this to the guitar.

In traditional African music the words of songs transmit moral guidance for the people listening. Does that figure in Cape Verde?

Pantera is doing something different; he’s playing with the idea of telling stories. Traditionally in Africa, and all over the world, music had that role of bringing stories from one place to another, and the moral dimensions of women’s life. I think in Cape Verde it’s also very important that there is a very strong sense of humour, at least I felt I can grasp the sense of humour in a lot of the things he says in the music.

Of course there was a lot of work in translating the lyrics, because he’s working with very old Creole, even with words that people don’t use anymore, to tell stories from today.

He’s playing with ideas of modernity and tradition, past and future. His music has past, and it has future. It’s not about what’s happening now, it’s about what the past brings to the present.

His social work was obviously important to him, especially with children.

He started very young working with music at social institutions for children. This is when he had a project with street kids, and the idea was not to take these kids to institutions, it was to try to find ways of getting them to do things in ordinary life.

One project was in the airport where kids helped passengers, and they would get some money for their families. He wanted to keep these kids out of prisons or begging on the street. And then he went to SOS villages, which are for children that either don’t have family or whose family cannot afford to keep them. The villages are divided into small houses; each house has a mother and about seven or eight kids living in the house. It’s a very interesting model.

When these kids are older, they move to an apartment, where they learn to be adults and start working, and he was working in this transition phase.

And talking with the adults that were kids when he was working there, they recall the music. So, we know he already played music with them, and the children in SOS villages knew the lyrics and the songs, even though the public didn’t. And for me that was also very interesting, because sometimes work with children is separated from real life, but he would sleep there, it was like a big family for him.

Carla, his wife, was a teacher for kids, so educating children was always being discussed. In 2000, it was a dilemma for Pantera to decide if he was going to be an artist or a social worker. Being a musician and an artist is in Cabo Verde often involves a bohemian lifestyle, drinking and so on. So, deciding to assume the ethos of a musician was always an issue.

It was not his nature to go on stage; he was a shy person. Maybe sometimes he had to drink a bit to get the courage to perform in public. I don’t want to romanticise the character of Pantera, because he was a real person with issues. You can hear it in his lyrics, when he says, ‘Vida está mareado, vida está complicado’.

“Life is complicated. Life is hard. I sit there at my bench, in my house, and I do this like a monkey, you know, I stay there all day, you know”.

This is one of his songs and then he says, “there are people starving in the villages in Cape Verde”. So, I didn’t want to say he was a genius. I don’t think there are any geniuses. I think there are real people that do music, and the more they can connect the music with their own lives, the more it works. I think the best music comes out of a place in life.

Arquivo Fundação Orlando Pantera

Arquivo Fundação Orlando Pantera

You showed Raiz di Polon, people dancing, and at the same time playing instruments. Did Pantera develop this?

I wanted to show that Raiz di Polon were developing this way of working in Cape Verde, and that they were influenced by Clara Andermatt and João Lucas, who were going to Cape Verde to find the musicians and people to work on a big project called Uma História da Dúvida, Story of Doubt.

Bringing live music to the stage and singing and playing the music, not sitting in a chair: “I play while I dance, while I do things, my whole body is playing this guitar”. This is a very strong language, that is very specific to the collaborations between Pantera and Raiz di Polon, and with Andermatt, the choreographer

It would be interesting to make a documentary about them; I was filming their shows and rehearsals for a long time.

Talking about the song Dispidida, that Pantera wrote after being in Lisbon, the disillusion seemed to come from having his first big contact with Europe and understanding that it’s no longer a village, people can’t be trusted and so on.

He was very enthusiastic at the beginning and the show was very successful, but it was not his nature to be going around the world doing shows. They included his music, but the shows were not his work, so he wasn’t sure he could trust these people to let him do his own thing. He was away for three years so he was also missing his family, especially his young daughter. Socrates, one of the characters in the film, explains it very well, saying that all participation in artistic projects is about giving and receiving.

But it needed to be more equal.

I didn’t want to make out that these were bad people, and he was the good guy. Life is very complex, it’s a dilemma when you have a project, and suddenly start to feel that you’re only going with the flow of other people’s projects. And since we know that this person died very young, it becomes important: you should decide what to do in life, because life is short.

I found this a very interesting part of making the film, these dilemmas created a feeling of ambiguity. We didn’t know what was really happening, but we have the feeling that something was not going well. This is very cinematographic, I did it by mixing in some archive footage where he’s sitting by himself, while the others are rehearsing, which brings this feeling of being left out and things slipping out of your control.

And isn’t that exactly what happens with every film? Once it’s been distributed, it’s gone, it’s something else for lots of other people?

It’s true, and sometimes, you finish the film, and you think: “oh, people are going to love it”, and then you show it somewhere and there’s hardly anyone there, and you start feeling “maybe I’m not doing this right, maybe people don’t like it”. There’s a lot of insecurity; creative work is like that.

Anything else to say?

The opening of the film in Lisbon was a very important moment for me. Not just because it was the first showing, but because Darlene came from Cabo Verde to see the film with her baby. Amir Pantera, her 5 months old baby is the future, Pantera is his grandfather. I decided to dedicate the film to this baby, and it was very emotional, because she brought the baby up on stage with us, and a lot of people were crying during the film. A lot of people came to me crying, because of the scene of the funeral, but at the same time, people were singing the music, so it was the right session, it was very, very good. And a lot of Cabo Verdean people came, which you don’t see so often in festivals in Lisbon, so I think the film could also bring different publics to documentary cinema. It’s very important, to go outside this small circle of critics and festivals, and get everyone talking to each other and commenting.