No Breathing! Reflecting Achille Mbembe

A response to Achille Mbembe’s “The Universal Right to Breathe”.

This conversation takes its initial steps from Achille Mbembe’s recent reflection on the current moment that humanity lives in light of the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. It was developed on the initiative of Luanda-based poet and art curator, Marcos Jinguba, in collaboration with the Visual Artist and Filmmaker Malebona Maphutse.

MM: In response to Achille Mbembe’s article in which he speaks of the intrinsic need to breathe, not only as humanity but as a collective body of living matter that includes the environment we inhabit for the time being. He speaks of the urgency for the environment, animals and humans freedom to breathe which requires an intentional understanding of humanity’s connection to the larger schema. This to me, is a beckoning call to recognise that we have a number of probable options that come with their limitations due to a number of socio-political reasons. Reasons that have evidently indicated the disparities in our “shared realities” even as connected as we may feel. For example, the call to socially distance, and isolate within the waking hours of the first hard lockdown in South Africa shed light to the continued disparities between privileged communities who could comfortably isolate for two weeks, communities in areas without the basic facilities such as water and sanitation as well people dealing with homelessness.

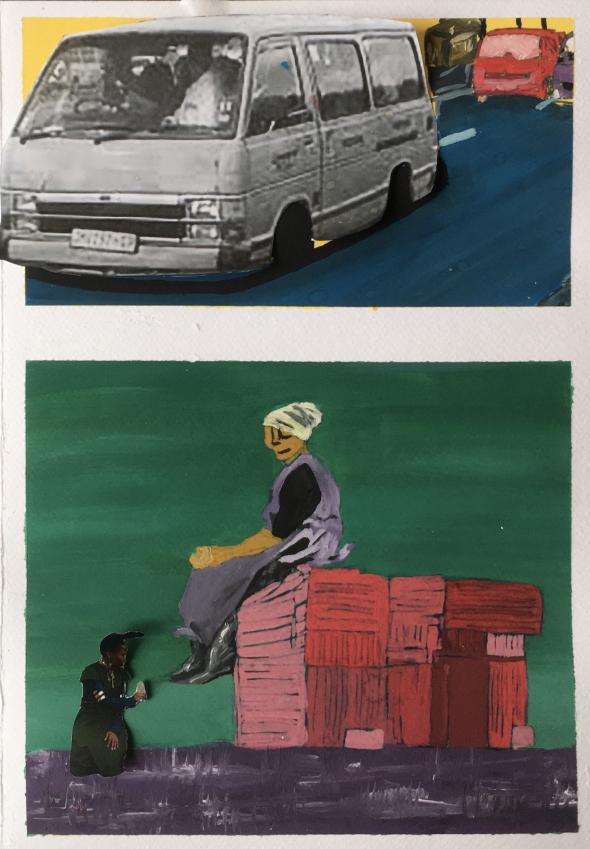

Image courtesy of the artist Malebona Maphutse

Image courtesy of the artist Malebona Maphutse

Making an anonymous apology to the article by Achille Mbembe, we elaborated the topic PROHIBITED BREATHING, because it is still questionable the legitimacy of being limited to obtaining oxygen, for example, in Luanda, it applied mandatory laws that triggered deaths for not wearing a mask and elsewhere, protests arose over their scarcity.

MM: The article by Achille, I think, significantly points out the legitimacy of being limited from obtaining oxygen, by explicitly pointing out that for some parts of the world where healthcare is part of organized neglect, we are faced with more than just the need to physically breathe. There is a prohibition of breathing that is systemic in nature which is part of a larger need for the freedom to breathe (live). For example the violent killings of black civilians by the police in South Africa due to an unchecked implementation of COVID-19 laws and regulations left us questioning the relevance (need) for policing systems embedded in colonial rhetoric. This, I think, is the vulnerability of life that Achille Mbembe speaks of.

Speaking of vulnerability. The world was faced with the Corona Virus and in seconds each state activated its defense system, however we noticed that the cyclical problems of the states, did not allow a good defense, in relation to the disease. How it looks at the distribution of health vulnerability, in South Africa, Africa and worldwide context.

MM: The vulnerability of South Africa’s public health systems was definitely highlighted because of the insurgence in COVID-19 cases. It brought to light the lack of services that the public had already been enduring due to years of ‘mismanagement of funds’ and corruption. It highlighted the number of people under and above the poverty line that depended and continue to depend on a crippled health system. CoronaVirus, in some way, served as an indicator (CW) of the structural issues that have been knowingly pushed aside for years and could no longer be ignored because the rest of the world was watching.

And on the body exposed to the environment, the human being is seen in recent times, as the explorer of fauna and flora to guarantee its existence, however some human communities still preserve the love of the land, timidly. But the question is, overexploitation of the land and environmental decay.

MM: I don’t really have much to say about this. I think there is a clear overexploitation of land and the environment that affects some communities more than others. However with that said, I think we are near a time where we cannot escape the effects of environmental decay because the land will in some way find a way to breathe even if it means removing us from the equation in order to survive. This goes to show that human beings are not above the earth but are of the earth. The realization that soon there will be more carbon and nitrous dioxide in the atmosphere than oxygen is a clear indicator that everything and everyone will be affected by humanities actions.

Isolation is an act that characterized this great moment of uncertainty that humanity lived in and we are increasingly asking ourselves about the usefulness of this word in artistic production. Personally, I was locked up for a long time, since the fear and panic about the virus was constant, and in a way very well spread by the media, but then there was a period of accommodation to panic about the situation.

MM: I was already a person that spent a lot of time isolated. My time alone helps me think, read and dream. However, the panic that came with the news of the pandemic meant that fear and anxiety had accompanied me into this state of isolation. It honestly did impact my production but it also put me in a position to question what productivity actually looks like as a multidisciplinary artist. Whether my mental work was as important as producing tangible items for sale and consumption. My time in isolation was equally spent on self introspection, by facing a number of issues I had chosen to breeze past because ‘life was so busy’. So since I no longer had that excuse, I had to face my demons and reckon with a number of ideas I thought I had already resolved. This state of uncertainty gave me space to really explore with a sense of acceptance and little less limitation due to time. It gave me a chance to write, think, conceptualise, without feeling like my ideas need to be finished for consumption and I am aware that is a privilege that wasn’t afforded to many artists.

Every culture involves the construction of collective memory and the words masks, hand washing, alcohol gel and various elements are part of the tales, novels, diaries and films that were taken at this stage. We can say that humanity has built a collective memory in common that will be able to determine the next times.

MM: It’s interesting that you speak of humanity having a collective memory. I found it so hard to separate myself from the collective happenings shared on social media but equally happening in certain geo-locations. And in these moments I felt like I couldn’t really be alone. I at some point felt a need to separate myself from the ‘collective’ experience and I have heard others utter this same feeling. I think that even in the collective memory that we have in common, there are so many nuanced encounters, memories and feelings we can never really have in common because we carry differences even in our sameness. I have found those in between individual memories are what will determine what is next.

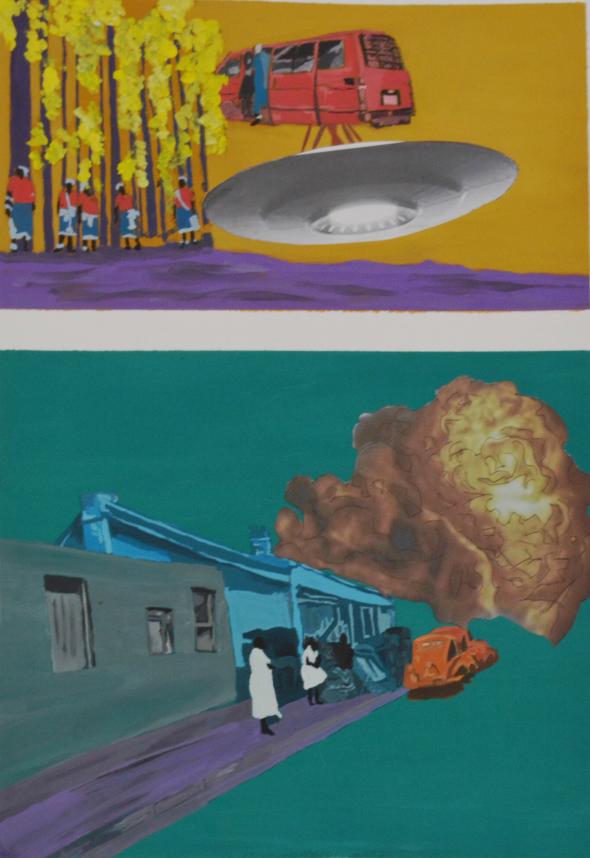

Image courtesy of the artist Malebona Maphutse

Image courtesy of the artist Malebona Maphutse

I don’t know if you agree, but the artist ends up being defined as a creative being submitted to the time he lives. The 17th century brought Illuminism as an artistic current, modernism in the 18th century and now, in the post-corona period, what it will see in artistic production for humanity.

MM: I think with regards to artistic creation imitating it’s time or the artist being seen as a product of their time, there is a sense of categorization I do not entirely agree with. I do agree that an artist’s experiences, history and environment deeply impact their work but I am not of the thought that a moment in time such as this will be the biggest catalyst for artistic production for humanity. One could argue that artistic production within the digital sphere may be a signifier for this time but I believe that we were already moving towards these modes of creation prior to COVID-19. I do agree that the pandemic may have accelerated the process a little. It has in some way brought to question the malleability of art institutions and their modus operandus. Which I find quite interesting as this may determine how artists exist within these institutions.

We know that racial ideological construction is still a colonial and historical heritage of mankind, the black being the center of this dilemma, but other “racial constructions” in the world are not left out. I use high commas here for the two words, because I believe that race is a project of time, based on beliefs until today without a clear foundation, but I do not rule out its existence as a system that delimits human relations and South Africa is a territory with many traces of this type of inheritance. It will be said that we can have a promising future for the race dilemma, after the pandemic, in the South African and global context.

MM: With regards to a promising future for the race dilemma in South Africa and the global context. I am subject to think that unfortunately the work of undoing systemic racism for South Africa and the global context is beyond the parameters of the pandemic. The pandemic may have seen us work through small victories albeit the questions of legitimacy with regards to activist organizations and ally intentions, I do think that race relations in South Africa are still being dealt with at the same pace as they were prior to the pandemic.