Occupy Wall Street: Carnival Against Capital? Carnivalesque as Protest Sensibility at Liberty Plazza

While some commentators and journalists have dismissed Occupy Wall Street as carnival, lawmakers and policemen did not miss the point. They reached back to an 1845 ban on masking to arrest occupiers wearing as little as a folded bandana on the forehead, leaving little doubt about their fear of carnival as a potent form of political protest.

The same New York Times journalist, Ginia Bellafante who expressed her lack of conviction in “air[ing] societal grievance as carnival” (NYT, 09-24), later warned against “criminalizing costume” (NYT, 09-30), updating her condescension to caution as she confirmed the police’s point: masking can be dangerous, carnival is serious business.

Carnival per se, the Shrovetide festival, hardly exists in the United States anymore, save for Mardi Gras in New Orleans and the West-Indian American or Labor Day Parade in Brooklyn, a pan-Caribbean celebration.

The carnivalesque, however, as medium of emancipation and instrument of political protest, is alive and well.

In fact, carnivalesque protests are a staple of the anti-corporate globalization movement. Direct reference to Russian semiotician and medieval carnival theoretician Mikhail Bakhtin underpinned the June 18th 1999 Global Carnival Against Capitalism or J18 waged by activist group Reclaim the Streets in London and across the world to coincide with the G8 in Cologne.

No such rhetoric seems to be at work on Occupy Wall Street. Yet, the Liberty Plazza encampment is under carnival’s sway, with its spontaneous community building and free communal feeding, bodies at play and trash on display, excess and refuse. Raised eyebrows about alleged sexual acts taking place in the Park and confessions of gluttony for the infamous OccuPie pizza are all indications about the pleasures of the senses and excesses of the flesh common to carnival – even under the duress of uncomfortable accommodation and police harassment.

But there is more than carnival symbolism to the occupation. Occupiers don costumes during demonstrations. The infamous Guy Fawkes masks of the Anonymous hacktivists are legion and they have found at least one legal defender (Jay Leiderman) to protect their masking rights arguing that as their sole common symbol, the mask is the statement, and therefore protected by the 1st Amendment. More interesting, maybe, than what has been described as an activist cooptation of a Warner Brother corporate product despite the relevance of Guy Fawkes, a reference to British carnivalesque tradition, are classic cases of hierarchy reversals, a carnival hallmark. These include protesters dressed up as billionaires, cocktail glasses in hand, and signs reading “austerity for you, prosperity for us.”

The recent Millionaires’ March, cacophonous as a charivari, belonged in the subversive realm of the carnivalesque as well. Other protestors made up as “corporate zombies,” spewing dollar bills from bloodied mouths. With Halloween coming up, they will no doubt make a come back.

And then there are the countless examples of personal ingenuity. For some, the message of the protest seems to be lost in translation. A helmeted woman in fur boots and beauty pageant or figure skating outfit was seen riding a gold and pink papier mâché unicorn. For others, the message is targeted. A young man dressed as what I would call a Zorro

Graduate, wearing both the black mask and gloves of the TV Mexican avenger and the equally black graduation hat and gown, held a convict’s chained bullet printed with the words “student loan” and a sign reading

“Unemployed Superhero, Master of Degrees, Shackled by Debt.”

Yet the most poignant message might be the simplest, exemplifying the merit of less is more, un-carnivalesque as that may sound: the photograph of a young blond-haired man, his mouth taped off by a dollar bill with occupy handwritten on it, has become iconic of the movement. Or maybe it’s because of the American flag tucked in his backpack, putting the whole scene into context.

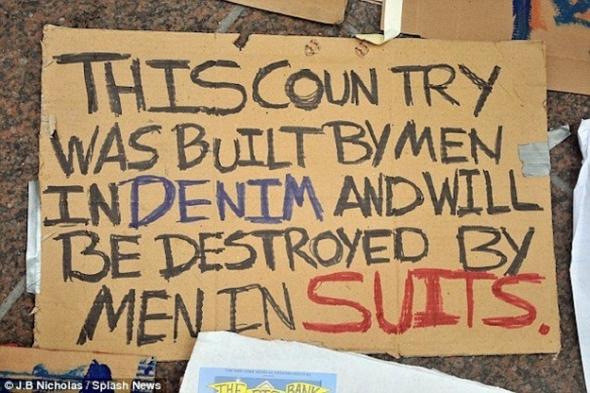

More minimalist yet, baring it all has been a strategy of (un)masking at Liberty Plazza. “This Country Was Made by Men in Denim and Will be Destroyed by Men in Suits” read a handwritten cardboard sign. In a corporate world where the clothes make the man, with men in suits (or banksters, tycoons, pundits, plutocrats, oligarchs, Masters of the Universe, malefactors, small thinkers, un-Americans) aka the 1%, protected by the blue shirts (regular police officers) and the white shirts (from the Paid Detail Unit of infamous pepper-spraying fame) against the occupiers (or ragtag, hippies, hipsters, activists, anarchists, anti-capitalists, crusaders against globalization, milquetoast radicals, un-Americans) aka the 99%, the spectacle of nudity is a good reminder of the common human nature of the 100%.

Whichever the costume or lack thereof might be, we shouldn’t see carnival for the costumes. Carnival is no friend of capital, and this Occupy Wall Street might well be another Carnival Against Capital.

Carnival in the Americas, from Trinidad and Tobago to Brazil, was a distinctive feature of colonial societies where proto-capitalism was experimented with on plantations. Colonization and slavery in the New

World replaced feudalism and servitude in the Old World and carnival occasionally accommodated a topsy-turvy world. And, at times, dissent under the cover of the mask turned into overt revolt.

But in stalwart carnival countries, the century-old festival has failed to bring a political momentum around key societal issues in the last couple of decades and has long been sold out to rampant consumerism and escapist fun, as remote from political relevance as any other mainstream entertainment.

In Trinidad and Tobago, which has a longstanding history of rebellion at

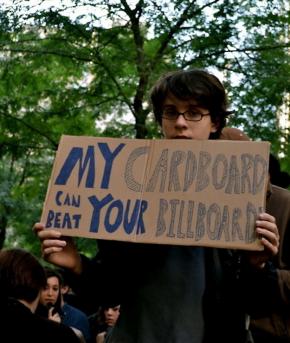

Carnival time made in China beaded bikinis sell for up to $US 2,500, turning exotic bodies into tourist commodities. The “ole mas” tradition (cardboard placards adorned with political slogans much like in Occupy Wall Street) which once offered a healthy public forum for political commentary is pretty much extinct, putting to the test one occupier’s belief that “My Cardboard Can Beat Your Billboard.”

In New Orleans, despite Ned Sublette’s assertion that second lines, the year-round carnivalesque parades of the black working class, “are in effect a civil rights demonstration,” as quoted by community organizer and social activist Jordan Flaherty, carnival itself remains an exercise in subtle segregation where Rex continues to stand on steadier ground than King Zulu.

Worst yet, those who believe Carnival to be a tool in the hands of the elite to keep the masses in shackle are given points for their argument when considering the following: Trinidad and Tobago is currently under martial law with little protest from the population to maintain its civil liberties against the constitutionally questionable drug-related security campaign.

And in the Big Easy, there are no floats to give Occupy New Orleans any traction yet. The movement, which started officially on October 6 has garnered only but scant participation thus far though The Times Picayunes’

Brendan McCarthy commented that “the procession had a second-line feel to it.” (TP, 10-06)

But then again, as James Gill reminds us, there never was a subversive tradition in the modern New Orleans carnival to begin with as “role-reversal fantasies would have been less likely to amuse the white elite than to fuel the fears of murder and rebellion to which slave-owning societies are naturally prone.” A stark contrast to 19th century New York where presumably white farmers dressed up as Indians to assault law enforcement officers – the very incident at the inception of the 1845 mask ban – maybe owing to its Pinkster legacy?

Scholars Peter Stallybrass and Allon White argue that “it actually makes little sense to fight out the issue of whether or not carnivals are intrinsically radical or conservative” and assert that “there is no a priori revolutionary vector to carnival.” Both skeptical journalists and radical protesters however, have made direct references not just to any revolution: to the mother of all revolutions, the French Revolution. The former mocked the latter’s disappointment that “the Bastille hadn’t been stormed” (Bellafante, NYT, 09-24 or 23?) only to later ponder “Carnival or Revolution?” (Catapano, NYT, 09-30), while the latter warned in a “memo to 1%: 99% are waking up. Be nervous. Be Very Nervous. Marie-Antoinette wasn’t” following Roseanne Barr’s call for the return of the guillotine. This revolutionary chorus is met with an anthropophagic crowd menacing that “One day, the Poor Will Have Nothing Left to Eat but the Rich” (or the short version: “Hungry? Eat A Banker”).

What is at stakes here is not so much whether or not the carnivalesque is at works in turning Occupy Wall Street into a revolutionary movement. Rather, it is the realization, through carnivalesque ritual strategy and hierarchy inversion, of the expanse (and expense) of the political antagonism and binary extremism between the 1% and the 99%. As much a site of resistance as a relational mode, the carnivalesque occupation of Wall Street is a symbolic struggle to break the high-low binarism that has besieged contemporary American society.

Beyond symbolism, if London’s Carnival Against Capitalism is any indication about the likely agency and possible outcome of New York’s own proto-carnivalesque protest, it might be in recounting the role it played in setting the stage for Seattle, the World Social Forum and other countersummits, enabling the tactical media technology behind the Indymedia project and prefiguring the current globalization of grass-roots counterglobalization and anti-capitalist movements.

London is back planning movements rather than surrendering to riots with an announced takeover attempt of the Stock Exchange or Occupy LSX on October 15 in solidarity with Occupy Wall Street. One cannot help but hope that, in New York as in London and wherever the movement might reach, the carnival cosmology will supplant the exchange economy and allow a repossession of the senses atrophied by dematerialized financial transactions.

But the real reversal of this carnival (or Purim or the Tadiabone), that old universal currency upgraded by social media, might well lie elsewhere, outside the United States, in the Arab World, the movement’s stated source of inspiration, setting the tone of this century’s worldwide wave of societal change, where American citizens might look a lot more like 99% of the rest of the world population, no longer in the privileged top 1%.

In so doing, this inversion of the world order would also help break that other binarism, between Western and Islamic worlds, and resist related reciprocal terrorism in which the body, as in carnival, is the weapon. So that to Rahul Rao’s question about what protest sensibility might befit a world in which there is not one single locus of threat, these protests and others to come respond that it might well be in the all-encompassing, inchoate and chaotic carnivalesque.

Staging their carnival in the middle of this 21st century form of Lent as recession, the Wall Street occupiers might seem to want to have their cake and eat it to. Beware though, that the Wall Street Bull ends up like the fattened Ox of Mardi Gras, sacrificed this coming Fat Tuesday, or the next Black Wednesday.