Colonial famines, archives, and silencing: Colonial Portugal and the (necro)politics of life

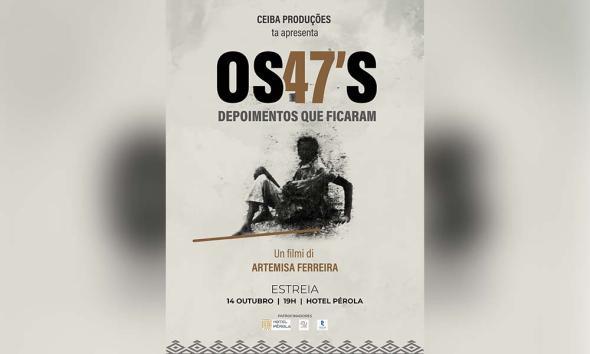

After the premiere in 2024, where “Mbongi Mbongi 67” was exhibited, and at Tabanka Sul, the documentary “Os 47’s - depoimentos que ficaram” (The 47’s - testimonies that remained), by Artemisa Ferreira, returns this time to Lisbon at Casa do Comum, through Frame Colectivo, an architecture, research, and art association, as part of an artistic residency integrated into the Cidades Fragmentadas (Fragmented Cities) program.

This documentary is a precise and meticulous work that approaches, with great sensibility, the tragedy of long, cyclical, and deadly famines that devastated Cape Verde throughout its violent colonial history.

The direct testimonies of the survivors and the reflections of various contributors on the famines that devastated the archipelago debunk the myth that the cause of so much death and misery was the harshness of a so-called “stepmother” nature.

On the contrary, the famine was, like José Vicente Lopes says, “Cape Verde’s holocaust”. The Portuguese colonial regime orchestrated this horrific crime by abandoning the islanders in various ways, even preventing them from implementing survival strategies. For example, it prohibited boats loaded with food sent by the Cape Verdean diaspora to help the starving people, to reach their destination.

Salazar, who controlled everything that was allowed to know about the reality of the colonies, attempted to “create” a fog around the islands, seeking to isolate them. People were dying of hunger, but nothing was written about it in the newspapers. This invisibility, based on a deeply racist Malthusian policy, allowed for the slow and silent death of thousands of Capes Verdeans whose names were not recorded in the archives. A double extermination.

“Os 47’s - depoimentos que ficaram”, narrates one of the darkest episodes of this trajectory: the Assistance Disaster of 1949, that victimized hundreds of starved people in the city of Praia, children, young people, and elderly buried without names in mass graves. A group of human lives reduced, as anthropologist Max Ruben says, “to a mere footnote in history.”

The famine shaped Cape Verde`s history, our identity and the way we relate to the materiality of life. However, there is still a huge amount of silence surrounding this fact. It would not be an exaggeration to say that we deeply internalized the censorship of colonial times, when it was forbidden to use the word “hunger” or indicate “starvation” as the cause of decease on death certificates.

Despite an epigenetic memory that has been passed down, hunger remains a “despicable” word that causes many people shame. This shame reveals our alienation from our own history. But, as historian António Correia e Silva states in the documentary, “hunger is a total social phenomenon,” an unavoidable element in understanding our history and, above all, our present.

One of the main reasons that motived Cabral and his generation to fight for independence was precisely the issue with famine. It was this battle that amplified the voices condemning colonial famine, exposing the empire of lies that was Portugal. This firm position “accelerated the engine of our history.”

It is inconceivable that today, half a century after the independence, does not exist a single day in our calendar (Gregorian-colonial) dedicated to the victims of famine or the Assistance Disaster. It is unjustifiable that, even to this day, the victims of 1949 remain confined to anonymity. It is equally incomprehensible that this issue does not prompt Cape Verdean society to engage in collective reflection.

When we hear one day, the “gritu’l Sisténsia” (Shout of resistance), just like Kaoberdiano Dambará challenges us, “ora al txiga” (Now he comes), as he prophesied.

This archival work by Artemisa Ferreira, who is also a teacher, offers us the opportunity to look at our history in an educational way.

We need to (re)create new fronts of liberation. Only a creative, anti-colonial education, such as the one implemented and experienced in pilot schools, drawing on the arts, cinema, and other ways of working with archives, memory, and the imagination, can make this possible.

May this second screening in Portugal open doors to more screenings in decent conditions. This is a work made with its own resources. Artemisa Ferreira has already contributed by producing and sharing this documentary film with us. It is now up to us to mobilize and do our part.

In Portugal, famine is a subject that is practically absent from discussions about the crimes of Portuguese colonialism. It seems that no one is interested. However, here too, under Salazar, there was hunger. Speaking about the 1967 floods that devastated Lisbon, journalist Diana Andringa points out that the floods publicly exposed the misery that the Estado Novo sought to hide, revealing the harsh reality of hunger in Portugal. Historically, the fascist and colonial regimes have been major producers of misery, using hunger as an instrument of control and domination.

The fact that neither the celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the 25th of April nor those of independence raised this issue should give us pause for thought. This year marks 76 years since the Assistance Disaster, in total silence.

All of this concerns reparations as practices of relations.

May these “47 testimonies that remain” not be buried under the rubble of silence, nor buried in the mass graves of history.

Thank you, Artemisa Ferreira, for your generosity, sensitivity, critical eye, and anti-colonial stance.