Glotophobia: from linguistic discrimination to accent racism

“In our society, language is a powerful and unrecognized instrument of domination and discrimination. Imposing your language as the only acceptable, respectable or reasonable one, and belittling, disqualifying or rejecting another person for their way of speaking, their accent or their vocabulary is as illegitimate as rejecting them for their religion, the colour of their skin or their sexual orientation – forms of discrimination more or less recognized and punished by the law in France”1. Discriminations based on language are, however, generally ignored, even though they affect thousands of people. Such discrimination is evidently connected to xenophobia, racism and social exclusion, but French sociolinguist Philippe Blanchet’s proposition allows us finally to name it: Glotophobia. This basic act allows us to denounce it and fight it as a form of linguistic discrimination applied to people whose vocabulary or pronunciation do not correspond to the dominant norms of the language. Like an identity card, the language that we speak and the way in which we speak it reveal something about us. It announces our social, cultural, ethnic and professional position, our age, our geographical origins… It announces our difference. To speak exposes us, and the act of elocution, which should be affirmative of self, can transform into a form of denunciation, an announcement of failing to belong to the dominant group.

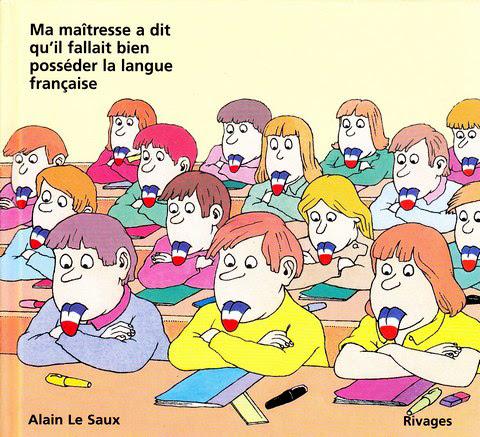

Ma maîtresse a dit qu’il fallait bien posséder la langue française | 1985 | Alain Le Saux

Ma maîtresse a dit qu’il fallait bien posséder la langue française | 1985 | Alain Le Saux

Instead of considering plurilingualism and linguistic plurality within one language as signals of vitality and the richness of the world and society in which we live, glotophobia denies them, belittles them and seeks to annihilate them. This is not just a rejection of a (real or supposed) characteristic of someone; it is a rejection of the person. Most concerning is the naturalness with which glotophobia as a form of racism is expanding unhindered. It is a visible and apparently inevitable social practice. It develops from excluding speakers for expressing themselves in one language or another (because they do not speak in the expected language as the language that must be spoken) to discrimination based on how a given language is used, through forms of speech that are considered inferior or incorrect (an accent, a way of speaking or writing, a particular vocabulary or register). Philippe Blanchet illustrates his study with French examples, but this can be transposed into other national spaces. In Portugal, for instance, there are endless criticisms of speakers of various regions for not using the Portuguese of Coimbra or of Lisbon. There are also commonplace stories about the linguist practices of emigrants and their children when they return for the holidays. This produces a form of humour constructed out of a stereotype propagated at the expense of speakers whose voice is denied both physically and vocally.

Reflecting on glotophobia also allows us to question the linguistic and cultural imaginaries of a post-colonial or decolonial perspective. We must rethink, again, discourses that rely on a political or ideological territorialisation sustained by references to the purity of origin, of language, of religion, or of ideological dogma2. This implies a necessary reflection on the role of the imaginary and power within the everyday practice and circulation of languages in society. It also reminds us of the importance of teaching languages in a world ruled by relations of domination which, if they are not deconstructed, continue to reproduce themselves from generation to generation.

Note: Ma maîtresse a dit qu’il fallait bien posséder la langue française is the title of a notable book by Alain Le Saux, author and illustrator of children’s books, published in n° 227 of La revue des livres pour enfants in February 2006 in the series « Francophonies ».

_________

MEMOIRS is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (no. 648624) and is hosted at the Centre for Social Studies (CES), University of Coimbra.

- 1. Philippe Blanchet, Discriminations : combattre la glotophobie, Editions Textuel, 2016, Paris. This situation is clearly not limited to France.

- 2. Émilienne Baneth-Nouailhetas, « Le postcolonial : histoires de langues », Hérodote Nº 120, 2006, p. 48-76