Mixed

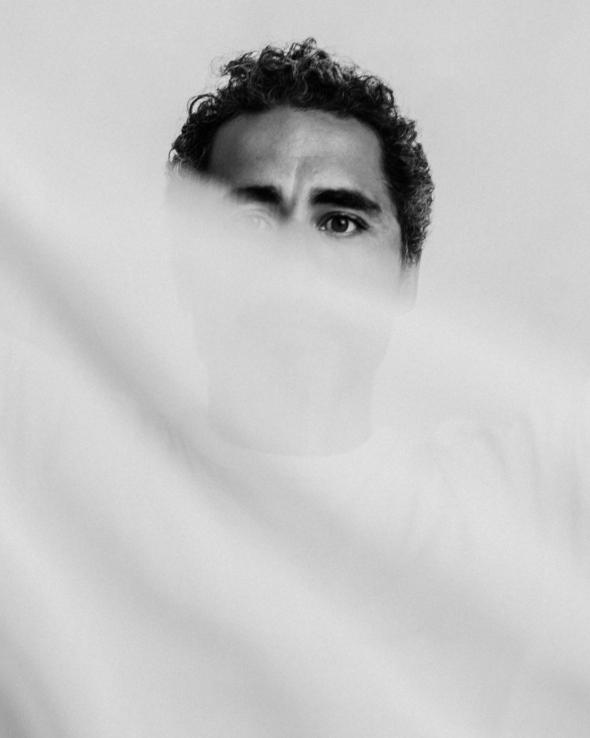

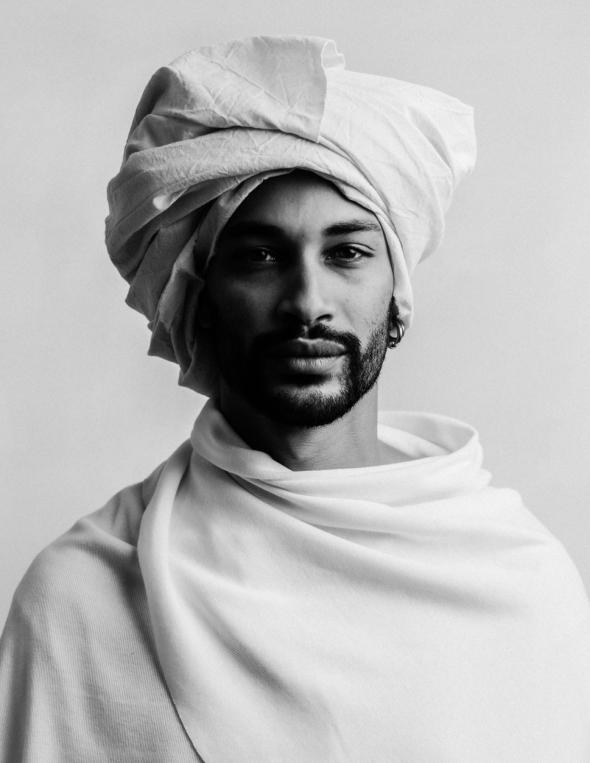

At its heart, MIXED is an exploration of racial and cultural identity. MIXED deals specifically with people that have mixed heritage, delving into the experiences of each subject that also echo his own. The series addresses the existential feeling of not fully belonging, while examining the cost of assimilation within society. The conversations focus especially on the contradiction of fitting in everywhere but nowhere at the same time and the resulting shoot is a collaboration that encompasses the themes considered.

The use of veils and fabrics in the images intends to provoke feelings and questions as to how we see others, and how we hope others make see us. Each session starts with a conversation that seeks to strip away those layers projected upon us, and that we wrap ourselves in as protection. The shoot only begins once we both agree that we have reached a place of unvarnished truth.

An ongoing fine-art documentary project, MIXED touches on tough themes such as racism, xenophobia and cultural suppression, yet is unashamedly hopeful. Mixed race people are living proof that different cultures can live and love together. In a time where racial purity is an unwanted part of the modern zeitgeist, and with the rise of fascism and right-wing extremism, it seems a poignant time to have this conversation about race. As the World becomes more globalised and interracial relationships are normalised, it is not just a refreshing realisation that the children of the future will almost certainly be mixed race but in reality, when we look at humanity’s history and our own DNA, we discover that racial purity is not simply undesirable but also a wholly unachievable ideal.

Beatriz

Beatriz

Beatriz was born in Portugal and counts herself as Portuguese. Her maternal grandparents are from Guinea-Bissau and from Cape Verde. Her paternal grandparents are from Portugal and Mozambique. Something that is rarely spoken about is that Africa is the most genetically diverse continent on the planet. Beatriz’s counts herself as three-quarters African, yet has light green eyes and fair skin.

Billy

Billy

Billy’s real name is Abílio, like his father and his grandfather. He was born in Angola and came to Portugal as a baby. His family left the country because of the civil war which went on with various pauses for 27 years. Although he has lived in Portugal for nearly the entirety of his life, he still describes himself as Angolan.

During our chat, the idea of home was a big theme. As a teen he started going back to Angola for Christmases and although he hadn’t lived there, he found the country reassuringly familiar because it was exactly as his parents had described to him growing up. However, though the country seemed familiar, he did not recognise it as his home despite being a self-described Angolan. Home to him was always Portugal. His mixed heritage comes from both his father’s and mother’s sides, who is Cape Verdean. During the First World War, his great-great grandfather was sent to live in Portugal from Austria. His daughter, then married a Spanish man and moved to Angola. Billy also has English heritage - his maternal great grandmother’s surname was Spencer.

Eric

Eric

Eric was born in Luanda, Angola. His father is from the north of Portugal, near the border with Spain and his mother is half Angolan and half Cape Verdean. His father was born in 1941, so for the first 34 years of his life Angola was still a Portuguese colony. A carpenter by trade, like his father and his father before him, the family took the decision to move to Angola when he was 16 in search of a better life. When Eric was 3, civil war erupted in Angola and the family were forced to relocate to Portugal. When Eric was 8, he travelled back to Angola to see his extended family and clearly remembers seeing the bullet holes in his family home in Luanda. He hasn’t been back since.

Eric talks openly about his identity crisis as a youth. Growing up in Lisbon he felt as though he was living a double life. At home he played the part of the dutiful African son, yet outside of the house with his friends he took on a very different, more European persona. He speaks Portuguese with a Lisbon accent up until the point that he gets angry or excited which is when his Angolan twang comes out. Eric describes his inner monologue as white, yet considers himself more Black than white. Even his hair mirrors his identity struggle as he was born with blonde, curly hair before it became completely straight. Every time he shaves it, it grows back differently.

Eric often gets mistaken for being Brazilian or North African. Once he even got mistaken for being Vietnamese. He believes that even though race itself is biologically insignificant, he likens it to a pedestrian crossing. In and of itself a pedestrian crossing possesses no meaning, yet the fact that cars slow down and stop when they approach means that we bestow meaning to it.

Jenifer

Jenifer

Jenifer was born in the small town of Columbia, Alabama. Her father, in her own words, is a “white redneck” and her mother was born in northern Florida to Japanese parents. Her father met her mother at a post football game party where they had a one-night stand. Her mother then fell pregnant with Jenifer at only 15 years old. Upon finding out that she was pregnant, she went looking for the father but he wanted nothing to do with her or the baby. Jenifer can count on one hand the number of times she has seen him.

When she was born, Jenifer’s mother left her in the hospital and the nurses alerted her paternal grandparents who took her in and raised her as their own. Her grandparents at no point throughout her childhood mentioned that they weren’t her parents until she was 13 when her biological mother sued to see her.

Up until that point it had never made sense why she’d felt so different and out of place. She had long, Black hair with tanned skin from playing outside in the Alabama sun. Her classmates called her Pocahontas as it was the closest reference they had, but had no idea of her Japanese heritage. Their first meeting ignited a crazy longing to find out where she was from as it finally made sense why she had felt so different. Jenifer pushed her grandparents to be able to see her mother, yet any enquiry would be immediately shut down. Finally her grandparents gave her an ultimatum - she could either continue living with them or she could go and live with her mother but she would be cut off if she did so. Jenifer chose her mother and moved in with her and her younger half-sister in Atlanta.

Sadly, the relationship with her mother soured as her mother became physically abusive to her and over the next 3 years Jenifer ran away from home regularly. As the abuse continued Jenifer found herself in and out of the Juvenile Detention System. Jenifer left home at 16, emancipated and moved out on her own and has had a successful life and career in multiple industries.

Although the 3 years with her mother were traumatic, it didn’t dim her desire to learn about her heritage and at 25 got a passport to travel to Japan which was an incredible experience. She says the most validating thing was that as soon as she arrived, the people immediately recognised her as mixed, which is something that had rarely happened up until that point.

Natalí

Natalí

Natalí was born in Buenos Aires to Brazilian parents. Her mother is from São Paulo and her father is from Bahía. She told me that she found certain parts of her upbringing tough to navigate. There is a fierce rivalry between Brazil and Argentina and that rivalry is particularly intense when the two teams play each other in football. She related the fact that she would often feel trapped by being in between the two, not wanting to root for one team over fear of turning her back on her heritage or her country of birth. Argentina has very Black people and was the only one in her entire school. As a child she recalls how she was called racist names and teased because she was different without understanding why.

Oscar

Oscar

Oscar was born and raised in Angola. His mixed-race parents both have heritage from Portugal and Angola. He left Angola when he was 15 and spent time between Portugal and the UK where he completed his A-Levels and now studies at the University of Sheffield. During our chat he told me that he thinks of his childhood in Angola as sad. That’s not to say he didn’t have good times, but Angola has a very complicated history regarding mixed-race people and towards homosexuality. After independence in 1970s there was well- documented persecution towards descendants of the Portuguese because it reminded people of their colonisers, and although this sentiment is not as strong as it once was, it does still exist.

In regard to Angolan views on bisexuality, Oscar said something very interesting too. Aside from the obvious rejection on religious grounds, he believes that the dislike is based more on the fact that bisexuality was used as a tool of torture to force slaves to be subjugated and as a form of punishment, and thus is also seen as giving into their white oppressors. Growing up he was very cognisant of the fact that he was bisexual, the example he gave was that he would watch Britney Spears’ music videos and think to himself that he was both attracted to her as well as her male dancers. The fact that he was so aware of his sexuality made it impossible to be totally at ease around a population that felt so strongly against him.

Raquel

Raquel

Raquel was born in Luanda, Angola. Her mother was born in Huambo in Central Angola and her father, although of Portuguese heritage, was born in Luanda. During the civil war, her mother, who was a military nurse, wanted to resettle in Portugal to escape the violence, despite her fathers protestations. They moved to Lisbon when Raquel was 9.

Looking at Raquel, it can be hard to place where she’s from exactly - many people ask if she’s Indian. Upon moving to Lisbon, Raquel describes the difference in attitudes and believes that in general Angolans are more welcoming than the Portuguese. In Angola, she was

often thought of as being European because of her lighter complexion, yet in Lisbon when she turned up at school her classmates saw that her mother was Black and immediately started calling her racist names and physically assaulting her. Thankfully, Raquel being the fierce person that she is, did not take the abuse lying down and fought back and was became known as someone not to be messed with.

Simon

Simon

Simon was born in France, but has lived in many different corners of the world. His mother is from Martinique and his father is French. He lived the first 6 years of his life in Paris before moving to London for 4 years, and then moving back and forth in between the two. In the years since, Simon has also lived in São Paulo, Venice, London (again) and currently lives in Lisbon.

Simon went to private schools both in Paris and London and says that if he didn’t look at his skin he could have easily been white because everyone else around him was. He would occasionally catch himself in the mirror surprising himself that he didn’t in fact have white skin. He clearly remembers the first time he encountered overt racism when he was with his mother in a McDonalds in Paris. He overheard a conversation between a father and his daughter on the table next to them. The father was saying, “You see those people over there, you should kill them”. Simon’s mother, who also heard the conversation, told him to just ignore them.

Simon is an artist and at present is very interested in sculpture and ceramics. His practice is based on the desire to heal the world and deals with creating new worlds, planets and galaxies. His belief that truth in our present reality is so hidden that it’s almost impossible to find and the only way to discover it is by creating new worlds. He has recently taken up a form of transcendental meditation that really resonates with him. The meditation omits the complications of skin colour by utilising the mantra “I am Light”.

Soya

Soya

Soya’s parents met at university in Casablanca and moved to Portugal because of her mother’s love of the Portuguese language as a result of watching Brazilian telenovelas. Soya was born in Lisbon, where she continued to live until she was 8. Her mother was born in Marrakesh and her maternal grandparents were Sudanese and Egyptian. Her father is half Ivorian and half Mauritanian.

When she was 8, her father decided to move Soya and her sister to Mauritania with the aim of her getting in touch with her roots. It was a difficult time being away from her mother, and as a result, being the de facto mother to her younger sister. Upon moving to Mauritania she immediately became aware of her race as people there would say that she was European and that she had lighter skin, which she took as a compliment at the time, but now realises that it was not. Another big culture shock was the approach to marriage that exists in Mauritania as polygamy is a common practice in the country. Reflecting on it now, family inbreeding is also very common and as a result many children are born with mental health issues. She speaks about the hyper-sexualisation of Black women and describes

Mauritania as being highly misogynistic where women exist to cook, clean and produce offspring. Even at the age of 12, there were grown men interested in marrying her.

After 6 years in Mauritania, Soya and her sister moved to Morocco for 2 years before finally moving back to Portugal at 16. Returning to Portugal, she was subjected to racism and high level bullying from her classmates had to move schools. After moving schools Soya began to come out of her shell and exude the self-confidence that she now has in abundance. When her mother died from ovarian cancer when she was 18, she became fiercely independent and career orientated. She recently finished her degree in International Affairs, is considering a Masters in either Diplomacy or Economic International Affairs and wants to work for the United Nations.

Sy

Sy

Sy was born in Luanda and lived in Angola until the age of 5 before moving to Portugal with her parents. Her mother is Angolan and her father is Portuguese. She describes her upbringing in Coimbra as very Portuguese as there are very few Black people in the north of Portugal. Until she was 16 she was the only child of African heritage in her entire school. Growing up she was on the receiving end of so many micro-aggressions that to protect herself she reimagined her life as a movie where everyone was out to get her because she had the leading role.

At school she describes times where her classmates would tell her that she had hair like a scouring pad. When she was younger she looked a lot like her dad and people would tell her that she was so beautiful except for her skin colour. Kids at school would make friends with her, then tell their parents would break up the friendship or wouldn’t invite her places because certain racist members of their family were going to be there. She was told repeatedly that she wasn’t from anywhere because she wasn’t fully white or fully Black.

The situation in Sy’s home was equally as toxic. Her parents met when Sy’s mum was 16 and her father had been in the war in Angola. Her father is 30 years older than her mum and she describes her dad as a racist. Her father would tell Sy that her African family were monkeys and their country was shit. As a result she hasn’t been back to Angola since she was a child. Her father would say that she was lucky because she had the strength of Black people but the intelligence of white people. He also wouldn’t allow Sy’s mum to teach her anything about her Angolan heritage, not even the cuisine. She tells me that everything she has learnt about Angola is as a result of leaving home. Despite this all, Sy is thriving. She is a Creative Director, works in marketing, has a bachelors in Political Science and International Relationships and dreams of one day having her own NGO.

Tiago

Tiago

Tiago was born and raised in Lisbon. His parents are from Cape Verde, but he has heritage from Goa and Guinea. Even though his family had money, he was always told by his parents that he would have to work harder than all of his white friends to get the same opportunities. Tiago’s a hugely talented chef and normally when he would start a new job, having turned up for his first day at the restaurant, the staff would immediately direct him to the dishwashing area as they thought that would be his job. He also tells me that he experienced racism from the families of previous girlfriends who didn’t want them dating a black man.

Vanessa

Vanessa

Vanessa was born in Portugal and grew up mainly in Sintra. Her mother is Portuguese but she has never met her father. When her mother was about 21, like many Portuguese in late 80’s, she decided to go emigrate to Paris in search of work. She became an au-pair for a Japanese family that owned an art gallery and while living there often visited a bar on the nearby Champs-Elysées. She soon met a pianist who used to play at the bar and had a short fling with him, however Vanessa’s mother didn’t speak very good French and he didn’t speak Portuguese, so they couldn’t verbally communicate at length. When she then fell pregnant with Vanessa and told him, he simply disappeared. Vanessa’s mother, after searching for him for a while, then returned to Portugal and gave birth to her.

Her mother describes Vanessa’s energy and physical features as being almost a mirror of her father. However, she knows very little about him. She knows that he also spoke a language other than French that she didn’t recognise and also that he was a musician that had emigrated from a non-European country that she had never heard of before. The result being that Vanessa has no real idea where he was/is from, nor his cultural heritage, and therefore her own ethnicity.

Vanessa finds it difficult to put into words the mystery about her ethnicity provokes in herself. She attempts to describe it as a mix of feeling unfulfilled with an open-hearted sense of empathy for various non-European cultures. It is an unconscious natural search for herself and although Vanessa feels more culturally familiar to some African countries through the music, food and her friends, the possibilities of where he might be from are endless. Just by looking at her, one could suppose that her father could be a number of different ethnicities.

When Vanessa was young, she would come home from school and recount the times that other children would ask if she was adopted. She lived until she was 8 with the assumption that her ex-stepfather was her biological father, yet on finding out that he wasn’t, even at such young age, she was not surprised. She never had truly felt him to be, due to having different physical features as well as never truly connecting with him.

Vanessa has questioned the theme of race since she began to observe the way in which was she was treated differently and how people used words like ”exotic” to describe her. A number of these experiences eventually instilled a sense of being an outsider trying to fit in, in a society misaligned to her, something that she didn’t feel was conducive to her personal wellbeing.

Although primarily a singer and performer, Vanessa is a multidisciplinary artist. Her personal work is mainly a hybrid of artistic expressions related to love, union, spirituality which she uses to connect with her ancestors, to explore and reflect on her own potential cultural heritages and to embrace and celebrate the empowerment of BIPOC communities. She allows a diverse set of rhythms, melodies and cadences to manifest within her while creating and even in absence of her father, she feels as though he is within her and that she has inherited his musical sensibilities. The feeling has become so strong that she decided to go look for him geographically. She will document the process and will begin the process by visiting the gallery owned by the Japanese family her mother once worked for.

Vânia

Vânia

Vânia is a Portuguese born Angolan dance creator and interpreter. Both of her parents are Angolan and traveled to Portugal as teenagers after Angola’s Independence from Portugal in 1975. One of Vânia’s grandparents and great-grandparents on either side was Portuguese and, because only those with direct Portuguese heritage were allowed to earn Portuguese nationality, her parents and family were allowed to leave Angola and move to Portugal. Vânia talks about her family having to negotiate where and when to perform their Angolan culture habits in order to fit in with the Portuguese, after all, Angola was left in a Civil War and Portugal was the saviour giving them an opportunity. [Vânia says this with a cynical tone].

Vânia lived in New York City for 8 years and it was during that period she began to fully embrace her heritage. While there, Vânia would say she was from Portugal to the inevitable “Where are you from?” questions. She soon realised that not mentioning her Angolan side was as good as denying it. Many Black people in the US have no idea where their families originated. This made her realise how much of her racial identity and how much internalised racism she had inherited from Portuguese culture. This was the very first time Vânia saw herself as privileged and that her African heritage was a thing to be proud of.

Being mixed is constantly feeling in-between, which makes it harder to belong. It often means being regularly asked where you are from and not being recognised as being where you actually are from. The complexity of genetics and the way people look, added to her racial identity conflicts that led to a late realisation of what she may identify as, independently from who is looking back. Because of that and how different people can look even within the same family (like her own), Vânia embraces the fluidity of her identification as it is constantly affected by the context, content and subjects in the conversation.

More about Theo’s work and exclusive interview.