A-terrar / Land-ing

The verb aterrar in Portuguese means to return to the earth, to land or settle. The act of landing can be ascribed to planes surveying the airspace, but also to spacecraft, whose orbital motion – like the celestial bodies themselves – takes place in the wider reaches of space, i.e., the cosmos. Here, I propose to look at a few works from the perspective of this apparently simple notion of landing bodies; entities that return and touch the earth, while keeping in mind that such an act reconnects bodies that sought to distance themselves – building overflight and distancing techniques – so as to produce the view of a body or “the view from a body rather than a view from above” (Strathern, 2004: 32). After all, aterrar is also the perspective of overflight of bodies returning to the earth through gravitational attraction.

It is possible to conceive of the idea of landing after looking briefly at The Blue Marble, the famous photograph of Planet Earth taken on 7 December 1972 by Apollo 17, which made it possible to visualize the Earth from afar by hovering over it. In this image, which brings nothing new other than the fact that it has become a commonplace representation of a certain global and univocal standpoint, the idea of touching down is mediated by an aerial and total overview that never seems to land. We can affirm that nothing remained the same after The Blue Marble, and ought to remember that this image is also the apex of the so-called “Ecological Age”, as asserted by Donald Worster in his brief history of the discipline1. Looking at the Earth from this unique perspective – that of a unified humanity which builds the devices of its visionary projections– coincides historically with the period called the Great Acceleration (1950s – now) and the acceleration of anthropogenic activities which produced the ecological crisis, studied presently as Anthropocene2, all the while crystallizing a holistic and aerial view of the globe mediated by images. In other words, this distanced vision in which the describer moves away from the represented object in order to visualize it, as in the technique of still life, overlaps with the acceleration of the extractive processes of terrestrial natural resources, as well as with the perspective of the planet as an entity that connects everything. Incidentally, let us remember James Lovelock’s involvement in this very same decade (1970’s) presented the planet as a living organism. Following his 1970s Gaia hypothesis:

It is possible to conceive of the idea of landing after looking briefly at The Blue Marble, the famous photograph of Planet Earth taken on 7 December 1972 by Apollo 17, which made it possible to visualize the Earth from afar by hovering over it. In this image, which brings nothing new other than the fact that it has become a commonplace representation of a certain global and univocal standpoint, the idea of touching down is mediated by an aerial and total overview that never seems to land. We can affirm that nothing remained the same after The Blue Marble, and ought to remember that this image is also the apex of the so-called “Ecological Age”, as asserted by Donald Worster in his brief history of the discipline1. Looking at the Earth from this unique perspective – that of a unified humanity which builds the devices of its visionary projections– coincides historically with the period called the Great Acceleration (1950s – now) and the acceleration of anthropogenic activities which produced the ecological crisis, studied presently as Anthropocene2, all the while crystallizing a holistic and aerial view of the globe mediated by images. In other words, this distanced vision in which the describer moves away from the represented object in order to visualize it, as in the technique of still life, overlaps with the acceleration of the extractive processes of terrestrial natural resources, as well as with the perspective of the planet as an entity that connects everything. Incidentally, let us remember James Lovelock’s involvement in this very same decade (1970’s) presented the planet as a living organism. Following his 1970s Gaia hypothesis:

“When we saw a few years ago those first pictures of the Earth from space, we had a glimpse of what it was that we were trying to model. That vision of stunning beauty; that dappled white and blue sphere stirred us all, no matter that by now it is just a visual cliché. The sense of reality comes from matching our personal mental image of the world with that we perceive by our senses. That is why the astronaut’s view of the Earth was so disturbing. It showed us just how far from reality we had strayed.” (Lovelock, 1988).

A few decades later, in 2019, as I now write this text from a window in my computer, the Earth is no longer a blue ball appeased by a totalizing perception of humanity. Plastics, dead satellites, greenhouse gases and different forms of contamination and radiation envelop the global view and confer to it certain immersive characteristics.

The Great Pacific Ocean Patch

The Great Pacific Ocean Patch

The planet agonizes. The Earth is touched upon as a subject of concern through the display of its “physiocide” and geographic proofs of malformation – like the famous plastic island (The Great Pacific Ocean Patch) that appeared in the Pacific Ocean in the second half of the 20th century – as well as growing environmental crimes, such as what happened in the Mariana (2015) or Brumadinho (2019) disasters, where many were washed away in the deluge of a more-than-political mud.

Disaster of Mariana (2015)

Disaster of Mariana (2015) Brumadinho (2019) Although depleted of the colossal perspective lent to it by space navigation in the 1970s, the idea of humanity as a species was progressively turned into an immanent geological colossus capable of influencing the world’s cardinal rhythms – or at least such has been the description of its reach. Anthropocene is the geological epoch of the human species, it is said, and the proof lies in the sedimentary deposits that originated in the first nuclear experiments held in the 1950s. What is of course ignored is that this idea of “species” was artificially inseminated by the normative and cisgender marriage between modernity and colonialism, and that the colossal perspective is still believed to stop and stand outside motionless in front of the globe, despite the fact that there are many wallowing in the mud, especially those who were not included in this unifying idea of humanity. The difficulty demonstrated by Western philosophy since the modern period to embrace a reflection (with)in the world – limiting itself, instead, to a hermeneutics of its own fiction, which is also the fiction of a human species and that of a planet seen from the outside – has contributed to this process. In The Life of Plants, Emanuele Coccia incidentally refers to Western philosophy as “a sort of Don Quixote of contemporary knowledge, engaged in an imaginary struggle against the projections of its own spirit; or into a Narcissus who looks back at the ghosts of its past, now empty souvenirs in a provincial museum. Forced to study not the world, but the more or less arbitrary images that humans have produced in the past, it has become a form of skepticism – and an often moralized and reformist one at that” (Coccia, 20183).

Brumadinho (2019) Although depleted of the colossal perspective lent to it by space navigation in the 1970s, the idea of humanity as a species was progressively turned into an immanent geological colossus capable of influencing the world’s cardinal rhythms – or at least such has been the description of its reach. Anthropocene is the geological epoch of the human species, it is said, and the proof lies in the sedimentary deposits that originated in the first nuclear experiments held in the 1950s. What is of course ignored is that this idea of “species” was artificially inseminated by the normative and cisgender marriage between modernity and colonialism, and that the colossal perspective is still believed to stop and stand outside motionless in front of the globe, despite the fact that there are many wallowing in the mud, especially those who were not included in this unifying idea of humanity. The difficulty demonstrated by Western philosophy since the modern period to embrace a reflection (with)in the world – limiting itself, instead, to a hermeneutics of its own fiction, which is also the fiction of a human species and that of a planet seen from the outside – has contributed to this process. In The Life of Plants, Emanuele Coccia incidentally refers to Western philosophy as “a sort of Don Quixote of contemporary knowledge, engaged in an imaginary struggle against the projections of its own spirit; or into a Narcissus who looks back at the ghosts of its past, now empty souvenirs in a provincial museum. Forced to study not the world, but the more or less arbitrary images that humans have produced in the past, it has become a form of skepticism – and an often moralized and reformist one at that” (Coccia, 20183).

However, between the outside view and the singular view, aterrar/landing can be understood as a counter-interpretative gesture that dismantles this unifying and custodial perspective, giving way not only to haptic knowledge (aterrar is to “touch” the Earth) but also to historical knowledge (aterrar is to “return”), thus producing a plane of immanence (aterrar is to immerse in the Earth, without distinction between that which acts and that which contemplates). Even when gliding, one can say that to land is be put in presence again, thus marking what has disappeared or what is agonizing. And with a return to touch, other models of connection and relationship with the very idea of humanity and the earth can proliferate. Aesthetical-political foundations are questioned, because – amid a wide range of views and touches – one seeks to make the difference whole, rather than produce the whole.

By associating these ideas, I have tried to select some contemporary works where the construction of particular visualities/visions/visualizations of the Earth invites us to perceive the act of aterrar/landing without making a distinction between “products” of culture and “facts” of nature.

Many of the selected works are produced by contemporary indigenous artists in Brazil or deal with indigenous rights in opposition to extractive and globalizing models, and form part of a more specific research that I have taken up on the dispute between indigenous and non-indigenous perspectives in the context of the Anthropocene. These are complete and yet non-totalizing perspectives that urge us to land or touch down in the face of the global extractive model. They are also more or less defined counter-visualizations to the totalizing anthropocentric view (the apocalyptic blue marble), aiming simultaneously to expand the possibilities of understanding the relations and frictions between what could be called “nature” and “humanity”, words that will tend to lose their meaning as the research process progresses.

1.

Denilson Baniwa produces some of the most impactful contemporary indigenous artworks in Brazil. Recently, in May 2019, at the 4º Mekukradjá – Círculo de Saberes, which took place at the Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, I heard Denilson assert that he was not able to differentiate his artwork from his broader political activism for the rights of indigenous peoples.

In the video A-gente Laranja [Agent Orange] (2019), the artist proposes to intersect recent images of chemical attacks on Guarani-Kaiowá populations perpetrated by fazendeiros (owners of large rural estates) in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul with archive images of American planes flying over and applying the herbicide Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was used in the 1970s as a defoliant in forest areas so that American soldiers could access disputed territories with greater ease. Although its harmful effects are well known, the current chemical attacks on indigenous populations in Brazil continue to be carried out shamelessly. By overlapping these images, Denilson Baniwa manages to interconnect archives and stories that upon first gaze would appear completely unrelated.

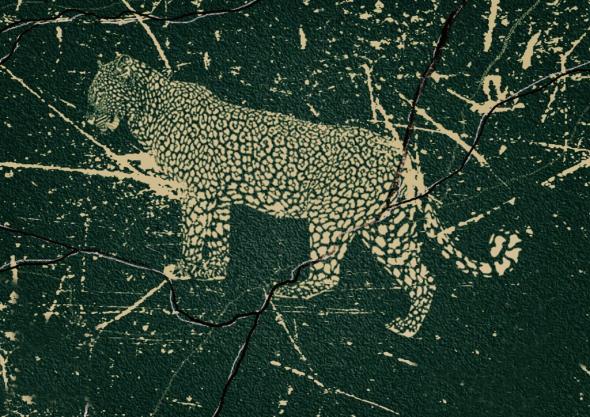

!['Natureza morta' [Dead Nature] (2016-2019), by Denilson Baniwa 'Natureza morta' [Dead Nature] (2016-2019), by Denilson Baniwa](https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2019/07/imagem_7_-_natureza-morta-desnilson_baniwa.jpg) 'Natureza morta' [Dead Nature] (2016-2019), by Denilson Baniwa

'Natureza morta' [Dead Nature] (2016-2019), by Denilson Baniwa

In the Natureza Morta [Dead Nature] (2016-2019) series, Denilson presents several views of the Amazon forest, which are commonly used as visual evidence of the area’s rapid deforestation. In a reversal of the primary function of these images, the aerial view of the patches is manipulated to represent the form of threatened bodies, such as the jaguar or an indigenous body. Here, the indication of absence has a double and dynamic meaning: the threat to indigenous modes of existence is linked to the biodiversity in/with which these communities co-inhabit. Thus, the aerial view of the uncovered land patches assails and consumes the view of the green and, in this interweaving, we can see an indigenous body in the forest come to light. The extractive vision is thus that of a “dead nature”, and the wordplay involving this figurative technique in Portuguese language is no coincidence (in Portuguese. the technique of still life is said to be a “dead nature”, that is, a natureza morta like the title of this work), just as in A-gente Laranja [Agent Orange] there is a game with a fraudulent meaning of “orange” (in Brazil, oranges are those who conceal the identity of fiscal and financial criminals).

In both works, A-gente Laranja and Natureza Morta, overflying the earth becomes a matter of return and recollection. The aerial view is instrumentalized as a mark of effacement and violence where natural history and indigenous history coincide. After all, the history of indigenous bodies is based on the erasure of a way of living “immersed” in the earth. In other words, the aerial view embodies the proof of a return to the earth’s “skin”, where the traces of erasure are inscribed.

2.

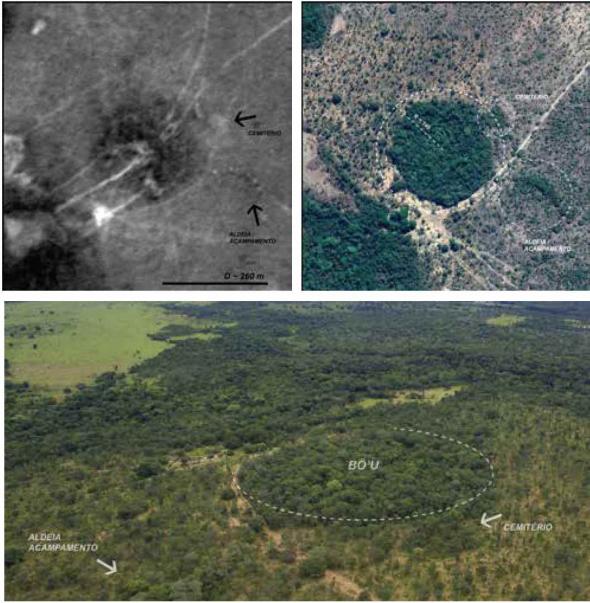

Trees, Vines, Palms and Other Architectural Monuments (2018), by Paulo Tavares

Trees, Vines, Palms and Other Architectural Monuments (2018), by Paulo Tavares

In the project Trees, Vines, Palms and Other Architectural Monuments (2018), architect and urban planner Paulo Tavares investigates the aesthetic-political problems raised by certain indigenous territorial struggles, focusing on the forced displacement of Xavante villages between the 1950s and 1960s in the state of Mato Grosso. In a documental installation consisting of photographs and videos (which can also be activated through conferences on the project), the project compiles aerial images of Xavante villages prior to the displacement, taken by the SPI (Serviço de Proteção ao Índio) and the North-American army, and compares them with current images where certain isolated arc and circle-shaped botanical patterns can be seen, coinciding with the architecture that is typical of these indigenous villages, also arched or circular.

Observed from above, these isolated green patches amid highly deforested territories are like “negatives” of the images of Denilson Baniwa’s Natureza Morta: botanical memory becomes the historical fact or architectural ruin of a history of land occupation. We reconnect to the idea that there is no clear separation between natural history and human history, and that “nature is what allows the world to be; on the other hand, everything that ties a given thing to the world is part of nature” (Coccia, 20184). Subsequently, Paulo Tavares, together with the Bö’u Xavante association, submitted a petition to the IPHAN (National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage) and UNESCO for the classification of these botanical formations as architectural heritage of the Xavante culture, furthering the idea that drove previous projects such as Selva Jurídica (2015) – in collaboration with Ursula Biemann – on the possibility of a “natural contract” (Serres, 1990) as opposed to a social contract (Rousseau), as well as the need to envisage the possibility of ensuring legal rights for the so-called non-humans.

3.

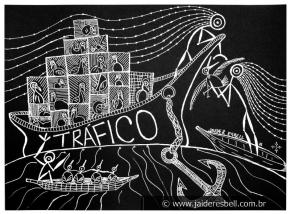

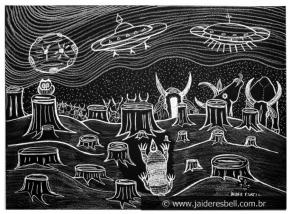

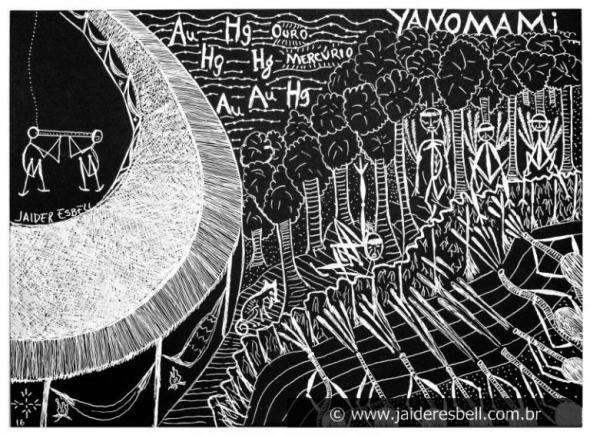

'It was amazon' (2016), by Jaider Esbell

'It was amazon' (2016), by Jaider Esbell

Taking the reflection even further (or closer), we can consider the act of landing or touching down without the use of aerial views. The series of drawings by Macuxi artist Jaider Esbell It was amazon (2016) connect data related to the colonial objectification of enslaved bodies to the extraction of natural resources and contamination of indigenous territories in Brazil. If we consider landing as the moment between overflight and return to the earth, in this case we can observe the coincidence between the perspective of colonial macro-history and Amazonian extractivism and the more approximated viewpoint of ethnocidal targeting of indigenous bodies – or, again, “the view from a body rather than a view from above”. Jaider Esbell’s work, as proximate as it is singular, unfolds through drawings and words and engages directly with the consequences of the supposedly impartial views of colonial history on the partiality of the affected bodies. Thus, in a recent exhibition entitled Vaivém at the Bank of Brazil Cultural Center in São Paulo, Esbell presented a very hard leather hammock – thereby incorporating the history of agribusiness in Makuxi territory – where one could read a text whose initial remarks were: “Indigenous people wait for justice while lying down in a cowhide hammock”.

A capitana conta a nossa história (2019), by Jaider Esbell. Photo by Edson Kumasaka

A capitana conta a nossa história (2019), by Jaider Esbell. Photo by Edson Kumasaka

4.

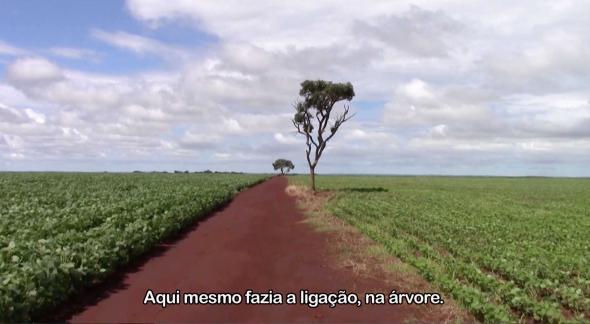

I would also like to add to the above sequence of works the film Ava Yvy Vera/ The land of the lightening people (2016), directed by a Guarani-Kaiowá collective of authors (Genito Gomes, Valmir Gonçalves Cabreira, Jhonn Nara Gomes, Jhonatan Gomes, Edina Ximenez, Dulcídio Gomes, Sarah Brites and Joilson Brites) from the Guayviry village, in Mato Grosso do Sul/Brazil. This is a documentary film whose process starts with the murder of leader Nísio Gomes and tries to reenact some moments of Guayviry community as it is reclaiming its originary land. It intersperses performative reenactements with testimonies of elders and a few narrative instances where the voice of a narrator – off-frame – provides commentary and tells stories in connection with different landscapes – most of which are deserted or excessively deforested due to intensive farming –, thus revealing their invisible layers.

Still frame from the film 'Ava Yvy Vera/The land of the lightening people' (2016), by a Guarani-Kaiowá collective of authors (Genito Gomes, Valmir Gonçalves Cabreira, Jhonn Nara Gomes, Jhonatan Gomes, Edina Ximenez, Dulcídio Gomes, Sarah Brites e Joilson Brites)

Still frame from the film 'Ava Yvy Vera/The land of the lightening people' (2016), by a Guarani-Kaiowá collective of authors (Genito Gomes, Valmir Gonçalves Cabreira, Jhonn Nara Gomes, Jhonatan Gomes, Edina Ximenez, Dulcídio Gomes, Sarah Brites e Joilson Brites)

In the first five minutes of the film, we see a close-up of a tree occupying the center of a landscape consisting of apparently innocuous ground vegetation. A deep voice speaks behind the camera though it resonates as a voice-over. The voice seems to speak about and to the tree, as it moves from behind the camera to the sequence shot, and it transitions between figure/image (tree) and background (cropped field), thus creating the momentary sensation that this person speaks not only about himself, but of himself and about/with the tree to us:

“I always came and stayed under this tree to connect. I did this every day. It was best at night. Only at night, it was not possible during the day. There are far too many gunmen here. There are many on the road and they never stop shooting. Because of this, I came at night. I couldn’t come alone during the day. Sometimes my godfather would accompany me, but I would usually come alone. I carried my borduna (type of cudgel) and came here. Right here is where I connected. I was miserable then… my life… I lived alone. I had no company. At that time, those who could keep me company stayed down there to take care of the place where the others are. I came here to call FUNAI and for the other partners to help us. And they say, “we will come tomorrow”. There was no mobile phone signal in that place. Only under the tree. We didn’t know there was a signal on the road yet. And my mobile phone was ordinary. If my mobile phone had a camera, I would take pictures of the people who did harm to us. I always made phone calls here. Here under the tree. This tree was like a tower for me.”

There is a sort of indecisiveness in relation to this locus of speech with/about/for the tree, not so much because the subject of the narration merges with the tree, but because the account, distended in the time of confrontation and contemplation, refers to a sort of companion interspecies memory shared in-between the voice and the tree. This tree “holds the conversation”; it is the proof, or document, rooted in the accident that is the history of that place, all the while indicating an area of indistinction between human and extra-human, human and nature, and also image/landscape and text/voice. The agency of the tree crystallizes this landscape as a zone of extinction: Ka’guy (in Guaraní, a word that could be translated as “forest” or even “nature”) and Anthropocene (the disappearance of Ka’guy) are fused in one.

As such, we can say that this view combines the subjective centrality of the speaker, the subjective centrality of the tree and the recollection of the forest that was once there, thus denoting its absence. A view which lands on a plane of relations and perspectives without the pretense of a view from above.

5.

Finally, and without wishing to impart a conclusive logic to this errant association of journalistic images, art projects or still frames, I would like to finish with an appeal to the wide range of perspectives under which we can look at, touch or return to the earth. The projects of Carolina Caycedo, an artist whose work has in part focused on the history of water and, in particular, of dams as “damned” mega-enterprises (thus the name of her long-term project Be dammed), are instigating examples of how to articulate different views and perspectives by combining outreach work with aggrieved populations of large corporative enterprises, indigenous perceptions on bodies of water and aerial and cartographic views of dams (she has predominantly worked on the mapping of large hydroelectric projects in Colombia and Brazil).

In her research on environmental conflicts, that does not separate the sphere of political intervention from aesthetic representation, Be dammed could not possibly be represented by a single image: justice to her work can only be rendered by visiting the artist’s website, which includes geo-choreographies, overlaps of aerial mappings, installations, serpent-shaped-books comprising various documents, conferences, demonstrations, petitions or memorials to murdered activists. In a way, one can understand that what matters here is not so much the position from which one looks at the earth, but rather the articulation between the bodies that look (at each other) through the earth. We are reminded that “geo-choreographies revive the use of the body as a tool of resistance to generate writings that firmly root us to the ground and relate us to the extra-human, producing a movement that expands both the body, be it individual or collective, and the place where we position ourselves” (Caycedo, 2016: 106).

6.

With no intention of equating this gallery to an exhaustive scientific article, I decided to open the way for a reflection on the different meanings of the act of aterrar that calls the crystallized and homogenized vision from the top (The Blue Marble or Anthropocene) into question. Many other possibilities of research remain unexplored in this text, such as the notions of queda/falling and enterrar/digging, that will be dealt with elsewhere in my research. For the moment I suggest, then, that we conclude as if we were getting ready to land, by looking down, in order to prepare for the road ahead (which is still down the road).

Note: This text was written for BUALA (www.buala.org) and is based on the author’s ongoing doctoral research entitled “Efeito antropocénico: crise ecológica e percepções humanidade-natureza nas práticas artísticas e etnográficas”/ “Anthropocenic effect: ecological crises and humanity-nature perceptions in artistic and ethnographical practices”, FCSH-NOVA e FFLCH-USP, Bolsa FCT SFRH/BD/128483/2017. Images of environmental crimes in Brumadinho and Mariana, as well as photographs of the Great Pacific Ocean Patch were taken from Google Images. The authors are unknown.

Bibliography

Caycedo, Carolina (2016) “A Fome como professora” in Incerteza Viva, Catálogo da 32ª Bienal de Artes de São Paulo.

Coccia, Emanuele (2019), Life of plants: a methaphysics of the mixture, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019.

Latour, Bruno, Face à Gaia, Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2015.

Latour, Bruno, “Anthropology at the Time of the Anthropocene – a personal view of what is to be studied”, American Association of Anthropologists, Washington, December 2014.

Lovelock, James (1988), “The Earth as a Living Organism” in Wilson EO, Peter FM, editors. Biodiversity. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219276/

Serres, M. (1990). O Contrato Natural. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

Strathern, Marilyn (2004). Partial connections. Updated Edition. AltaMira Press. Originally published in 1991 by Association for Social Anthropology in Oceania.

Photos and Films

A-gente Laranja, Denilson Baniwa, 2015

Natureza Morta, Denilson Baniwa, 2016-2019

It was amazon, Jaider Esbell, 2016

Ava Yvy Vera/A terra do povo do raio, Genito Gomes, Valmir Gonçalves Cabreira, Jhonn Nara Gomes, Jhonatan Gomes, Edina Ximenez, Dulcídio Gomes, Sarah Brites e Joilson Brites, 2016

The Blue Marble, 1972. Apollo 17 and NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/content/blue-marble-image-of-the-earth-from-apollo-...

- 1. Donald Worster, “Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas”, 1977.

- 2. Scientifically, the analysis of Anthropocene involves the crossing of data on nature (the rise of carbon emissions, sea levels, global temperature, melting velocity, extinction of species, ocean acidification, etc.) with human data (increases in human population, GDP, etc.), creating the phenomenon now called the Great Acceleration by scientists and observed ever since the 1950s. These anthropogenic effects on the climate would be largely irreversible, as pointed out by the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) of the International Stratigraphy Commission, which has been studying the phenomenon. To learn more about the AWG, see: https://www.nature.com/articles/541289b?foxtrotcallback=true=true.

- 3. English translation available here: https://books.google.pt/books?id=5B EDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA8&dq=life+of+plants&...

- 4. English translation available here: https://books.google.pt/books?id=5B EDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA8&dq=life+of+plants&...