The Vital Matters of António Ole

The organization of the territory is a mere matter of nature.

António Ole

António Ole, Untitled, 2006, video still

António Ole, Untitled, 2006, video still

António Ole: Vital Matter gathers works from different periods of António Ole’s (Luanda, 1951) multifaceted artistic journey of over fifty years. Made in various media, from sculpture to photography, from drawing to video, these works highlight the attention that Ole has devoted to nature and its vital elements and materials. The earth, water, fire and air here take on countless forms that, as a whole, invite a planetary perception and an ecological awareness not only of the cohabitation, but, above all, of the interdependence between human and non-human forms of life (animal, vegetable, mineral) – vital matter to whose urgency the pandemic itself has, more than ever, alerted us. The survival of the human on our planet will depend on this deep awareness, combined with consequent forms of action. The lessons to be learned will be ways to unlearn the obsession with economic development and growth and the constant acceleration of production and consumption at the expense of the necessary environmental balance.

If, on the one hand, Ole’s interpellation is planetary, on the other hand, his affective geographies in Angola and the African continent are no less present, posing a series of fundamental questions. Since both perspectives – one more global, the other more continental, regional and local – are intimately interconnected in his work, in this context they cannot fail to refer also to the fact that the globalised dynamics of exploitation (of labour) and extraction (of resources) have been going on for several centuries and with special violence on the African continent. It should be borne in mind that the colonial project was, above all, economic and that, as several African theorists remind us, more than finished, it seems to have been transformed and adapted, acquiring new configurations after independence and the culmination of the cold war, with the complicity of several African elites.1 Such a project also implied epistemicidal processes, i.e. insidious forms of annihilation of knowledges, practices, languages and spiritualities, many of which, nonetheless, survived through countless strategies of resistance on both sides of the Atlantic.2 Both the extractive and the epistemicidal dimensions of western and westernized modernity had consequences in environmental terms, disturbing the material and spiritual balances of ecosystems, their rhythms and knowledges, and thus fracturing ontologies and epistemes, ways of being and knowing. As Ruy Duarte de Carvalho has shown us, other forms of modernity – modernity as a balanced adaptation of the human to the surrounding environment – erupt in resistant ancestral ways of life;3 while progress often reveals itself as a synonym for death.4 Along the same lines, through the traces of drawing, collage and text, Ole states that “the organization of the territory is”, or should be, “a mere matter of nature” (Soul & Circumstance III, 2016).

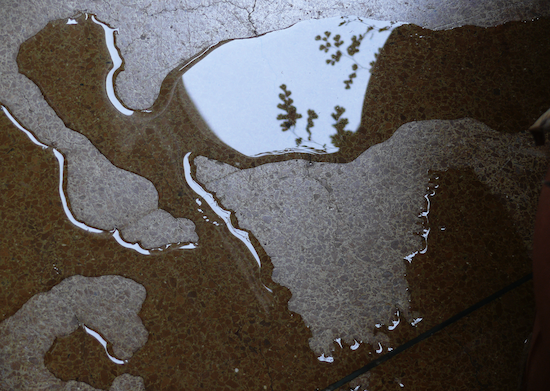

António Ole, Wet Triptych, 2013, photography in light boxes, detail

António Ole, Wet Triptych, 2013, photography in light boxes, detail

Armed with a broad and acute historical awareness of the present (without which the horizons of the future are extinguished), and without giving up the universality (mondialité) inherent in a Creole cosmopolitanism and the freedom of aesthetic experimentation with a multiplicity of media and influences (which his biography between Africa, Europe and the Americas stimulated),5 Ole’s planetary interpellation never failed to permanently summon the epistemic strength, the cultural and spiritual wealth, and the multiple modernities and ancestries of the African continent, of its numerous diasporas and, in particular, of Angola. With a work markedly attentive to the rhythms and faces, the materials and constructions, the urban surfaces and textures – in particular, of Luanda, its slums or musseques and its islands –, from an early age Ole also observed that other Angola so dissimilar from the capital, its diverse landscapes and ways of life. António Ole: Vital Matter unveils, precisely, some of these other rhythms and textures, the vital matters beyond the walls and the skin of the city.

The surfaces in evidence here are those of the baobab trees from Kissama and Massangano, areas located to the south and southeast of Luanda, respectively (Triptychs from Kissama and Massangano, 2006). These close-up vegetable landscapes are curatorially interrupted by the light beams of Silent Voices I (2000), that is, by the energy or luminous matter whose displacement through cosmic space and time exceeds the scale of the human and the planetary, narrating, in the its silent voice, the history of the formation of the universe itself, of its stars and galaxies; energy or solar matter on whose fire and heat depends, in the right measure, and with the proper dose of indispensable shade, life itself on Earth. With the planet overheated, the ices melting, the lands flooded, and the forests burned as a result of polluting human action (by the most industrialized nations), the lack of shade will lead to extinction.6 At the same time, the lights and shadows of Silent Voices are also those of artistic creation, since, despite the silence of their near abstraction, they were photographed among the voices of the interior architecture of the Teatro Elinga, in downtown Luanda, where, for about two decades, Ole installed his studio. As far as light and shadows in Luanda are concerned, it should also be noted that, even after the end of the civil war (1975-2002), access to essential goods such as electricity and water remains deficient and unstable, with a generalized impact on the life rhythms and survival strategies of the approximately eight million inhabitants of a city, which the dragging out of the war in other parts of the country over twenty-seven years overpopulated.

António Ole, Kissama Triptych, 2006, photography, detail

António Ole, Kissama Triptych, 2006, photography, detail António Ole, Massangano Triptych, 2006, photography, detail

António Ole, Massangano Triptych, 2006, photography, detail

But the close-up vegetable landscapes of Kissama and Massangano appear interrupted not only, curatorially, by the juxtaposed work with which they dialogue, but also in themselves. The proximity with which Ole photographed the baobab tree trunks invites, on the one hand, a careful look at the textures and “veins” inherent to their vegetable and arboreal condition and at the marks that the passage of (chronological) time and the climatic conditions have imprinted there. On the other hand, this same proximity also causes a vague abstraction, in which the vegetable texture, for a moment, almost appears animal or mineral. The approximate focus also invites the observation of the inscriptions left by the human presence and the temporality of history. On one of the trunks, next to actual stones, we read “Moreira” and “Lisbon”, words that immediately evoke the spectres of the colonial war / war of liberation (1961-1974), or perhaps more recent presences. The Kissama national park was founded in 1938 as a game reserve, having been transformed into a national park in 1957. In addition to hunting, the several uninterrupted decades of the war of liberation and the civil war have had a strong impact at all levels – mainly human, but also environmental – in this and countless other areas of the country. One of the consequences was the devastation of flora and fauna and the near extinction of some species, among which stands out one of the national symbols, the giant black sable. After the end of the civil war in 2002, the Kissama park was reactivated, initiating several projects for the conservation of its ecosystems, such as the international partnership with Botswana and South Africa, which has repopulated Kissama and other regions of the country with the animals that the war had annihilated.7 Indeed, the density contained in Ole’s vegetable surfaces comes not only from their material thickness, but also from the many centuries of history that they tell, both natural and human, since, going back to the 16th and 17th centuries, the Kissama region (among others) also evokes the history of African resistance to the progressive Portuguese colonial occupation, as well as to the routes that, from the interior, led the enslaved Africans to the coast and, from there, to the mines and plantations of the Americas. According to some authors, Kissama harboured communities resistant to the coloniser and to slavery that, unlike the more stratified political formations of the various kingdoms that fought against the Portuguese colonial presence (such as Ndongo and Matamba, led by Njinga Mbandi in the 17th century), resembled the quilombos that emerged on the other side of the Atlantic.8

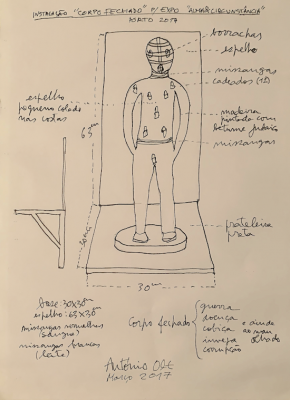

António Ole, Study for Closed Body, 2017, drawing

António Ole, Study for Closed Body, 2017, drawing António Ole, Closed Body, 2017, sculpture

António Ole, Closed Body, 2017, sculpture

As to Massangano, a village located in Kwanza Norte, east of Kissama, near the confluence of the Lucala river with the Kwanza river, it was the setting for events that marked the country’s history. In 1580, the Portuguese defeated King Ngola Kiluanji (father of Njinga Mbandi) in the battle of Massangano, having been repelled in 1582, when, under the command of Paulo Dias de Novais, they tried to penetrate the interior in search of the Cambambe silver mines. Built in 1583, the Fort of Our Lady of the Victory of Massangano guaranteed and made it possible to expand the Portuguese occupation of the region, also supporting commercial routes such as those of the trade of enslaved people.9 It was the first of several forts built along the Kwanza. In 1640, the fort was attacked by Njinga Mbandi, and it was there that, in the face of the Dutch occupation of Luanda in 1641, the Portuguese withdrew until Salvador Correia regained the capital in 1648. However, it is not the ruins of the fort of Massangano that Ole shows us. These several layers of history emerge poetically condensed in the roughness of the millennial trunks of their baobabs, silent witnesses to and survivors of centuries and decades of conflict, authentic ecosystems in themselves, shelter of countless vegetable and animal species, including the human. Resistant to drought, donors of precious fruit, the baobabs (and other figures of nature) are also sacred and animistic matter, guardians of ancestral existences and knowledges, bearers of myths and spiritualities, symbols of ancient wisdom. Almost abstract, seemingly unveiling the silent enigma of an illegible writing or of a confused map, their trunks also recall the orality of the stories told around them. Indeed, the gesture of drawing apparently abstract shapes (in the sand) is, for some Angolan peoples like the Tchokwe, a way of telling stories.

Knowledgeable of the varied cultural and spiritual production of the various peoples of Angola, from the Tchokwe of the Lundas, in the northeast, to the Mumuíla of Namibe, in the southwest, which he has learned about and admired in proximity to important names of Angolan anthropology such as José Redinha and Ruy Duarte de Carvalho, respectively, Ole nonetheless plays with Western expectations of African art, from the traditional to the contemporary. Therefore, a certain enigmatic ambiguity marks the sculpture Closed Body (2017), while the drawn Study (2017) that prepared it, and which accompanies it here, offers some interpretive clues. Ole shows us a black human figure, formally inspired by some traditional African statuary (like the nkisi, fetishes from the Congo and northern Angola), whose coordinates, however, he shuffles with the materials and objects with which he adorns his sculpture: he retains the usual front mirror, but places it on its back, facing an equally mirrored background that returns the figure’s back and our own image, in a kind of mise-en-abîme; he retains the typical nails, but adds padlocks that also close the eyes and mouth, maintaining, however, the possibility of opening them with the keys that surround the ankles. Despite the differences he introduces, Ole preserves the spiritual and protective nature of the figures which have inspired him, designed namely to appease the aggressiveness of spirits and other negative forces. His figure carries the protective invocation to contemporary times, shutting himself off from the energies of war, disease, greed, envy, corruption and the evil eye – evils that, although universal, have affected Angola with special virulence. If, on the one hand, the padlocks and a kind of rubber mask that surrounds the head of this ambiguous figure do not fail to evoke, while paying homage to, the ancestors who were subjected to and resisted slavery and forced labour, on the other hand, they also refer to more contemporary prisons, censorship and resistance. Despite the figure’s male appearance, the redness of the blood and the whiteness of the milk, in the beads, reinforce the opening of this Closed Body to female vital fluids and rhythms.

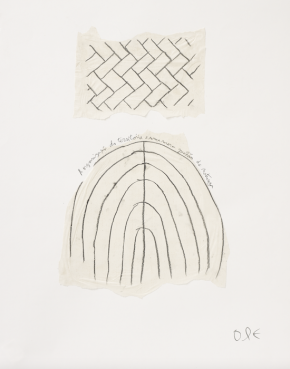

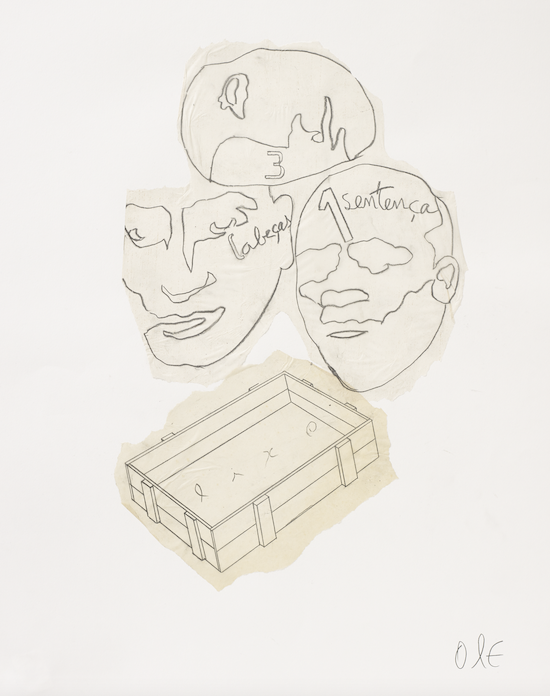

António Ole, Silent Voices (I), 2000, photography, detailSome of the questions elaborated by this work resonate in the series of drawings and collages on paper Soul & Circumstance (2016), made around the same time. The “mask”, a spiritual, iconographic and performative element so relevant to African cultures (among others), associated in particular with ancestral initiation rituals and inspiring fear and reverence, also appears here as a “cursed thing of the mirrors” in the sense of duplicity: underneath the mask it only seems possible to find another one (S&C VI). “Consciences” are stifled “for an authoritarian reason” (S&C IV), since to “3 heads” of masked semblance there only seems to be able to correspond the “trash” bin of the false consensuses imposed by the dictatorship of “1 verdict” (S&C VIII). Ole asks us “what is the heart for?”. Besides “passion”, a hand and a head point to two hearts, whose veins and arteries evoke the pulsating roots of vegetable beings, and where a uterine ovular circularity is glimpsed. From the hair of the rested head, apparently female, emanates the symbol of infinity and “a bow from the spine”. We are all, without exception, human and non-human, “living with that inside” (S&C V) – with that fragile but powerful vital mystery, whose rhythm moves us and escapes us. In fact, “about the creation of the universe” that we inhabit, “there is only an increase in the mystery”, the micro- and macrocosmic enigma for which we seek the infinite and fugitive answer, saved only by the equally potent mystery of the embrace and by the shared energy of the common (S&C VII).

António Ole, Silent Voices (I), 2000, photography, detailSome of the questions elaborated by this work resonate in the series of drawings and collages on paper Soul & Circumstance (2016), made around the same time. The “mask”, a spiritual, iconographic and performative element so relevant to African cultures (among others), associated in particular with ancestral initiation rituals and inspiring fear and reverence, also appears here as a “cursed thing of the mirrors” in the sense of duplicity: underneath the mask it only seems possible to find another one (S&C VI). “Consciences” are stifled “for an authoritarian reason” (S&C IV), since to “3 heads” of masked semblance there only seems to be able to correspond the “trash” bin of the false consensuses imposed by the dictatorship of “1 verdict” (S&C VIII). Ole asks us “what is the heart for?”. Besides “passion”, a hand and a head point to two hearts, whose veins and arteries evoke the pulsating roots of vegetable beings, and where a uterine ovular circularity is glimpsed. From the hair of the rested head, apparently female, emanates the symbol of infinity and “a bow from the spine”. We are all, without exception, human and non-human, “living with that inside” (S&C V) – with that fragile but powerful vital mystery, whose rhythm moves us and escapes us. In fact, “about the creation of the universe” that we inhabit, “there is only an increase in the mystery”, the micro- and macrocosmic enigma for which we seek the infinite and fugitive answer, saved only by the equally potent mystery of the embrace and by the shared energy of the common (S&C VII).

António Ole, Soul and Circumstance (III), 2016, drawing and collage on paper

António Ole, Soul and Circumstance (III), 2016, drawing and collage on paper António Ole, Soul and Circumstance (VII), 2016, drawing and collage on paper

António Ole, Soul and Circumstance (VII), 2016, drawing and collage on paper António Ole, Soul & Circumstance (VIII), 2016, drawing and collage on paper

António Ole, Soul & Circumstance (VIII), 2016, drawing and collage on paper

About ten years before making the series Soul & Circumstance, but echoing strongly in it, and at the same time and in some of the same landscapes in which he photographed the Kissama and Massangano Triptychs, Ole filmed the video Untitled (2006). Despite the strong presence of Angola, this work is, in fact, a journal of multiple journeys, a notebook of visual and sound notes collected from various points of the globe, both in the north and south. Such notes are accompanied by the artist’s own voice-over, saying some of the poetry gathered in the important collection Rose of the World – 2001 Poems for the Future, which, in 2001, disseminated, in poetic form, creation myths and cosmogonies originating from various parts of the world.10 Amid the sound of the wind, leaves, birds and some musical instruments, and quoting the words of ancient poets, the artist’s voice expresses wonder at the beauty and gift of nature and incomprehension for the violence of human action. He elaborates poetically about the mysteries of the soul “that embraces everything” and the “inexhaustible” universe (even if the human ends up exhausting itself), of spirit and matter, of life and death, of infinity and finitude – binomials existentially intertwined, which only the artificialities of some Western thought untie, but which life, spirituality, popular wisdom and other philosophies, other ways of being and knowing soon take care of interweaving again. “Intimate boats”, utensils, sails, “the blocking of the riverbanks that embrace unexpectedly other possible journeys by land, by tree, by pier, inside each one and each thing”; dry havens without a source and ashless hells without a flame; the “faithful hostel” of woods, fields and hills; the riverbanks and fountains “where the body bathes and clean rises”; princes clearing forests, with their guides and soldiers girding trees and alerting elephants; the heart left “on the mountain, by the stream, beside the heather, near the birds”. The motif of the double masks also emerges here, through the image of the fragment of a larger installation with which Ole paid homage to his father in 2006. In the video, the striking image of the white mask covered by a respiratory protection mask proves to be incredibly prescient in relation to the current pandemic moment, which, caused by the excessive deforestation that brings humans closer to animal species carrying viruses, today affects all regions of the globe, forcing humanity to slow down.

The exhibition then extends to the outdoors, stopping, before exiting, in the interstitial space of Wet Triptych (2013), already turned towards (and visible from) outside, but still located inside. Indeed, the photographic images themselves, which make up the triptych in light boxes, are also images of an interstitial space. They portray the domestic interval, between the interior and the exterior, of Ole’s balcony in Luanda, and the ephemeral freshness that follows the watering of plants. In a somewhat abstract and indirect way, they show the materials of the floor, the vases and the plants, as well as the earth, water, light and air that feed them. The watercourses draw liquid maps, in which water seems to take the place of the earth and the shape of strange continents, with their straits and peninsulas. The intervals of light reflected in the water, amid the shadows, reveal vague vegetable beings, which the light boxes, in turn, rekindle.

António Ole, Untitled, 2006, video still

António Ole, Untitled, 2006, video still António Ole, Untitled, 2006, video still

António Ole, Untitled, 2006, video still

These liquid images finally lead to the outdoor space, where air circulates freely, and we find Lookout (1994). In a way, the exhibition ends as it started: like Closed Body, visible on arrival, Lookout constitutes a kind of sculptural altar, offering the possibility of overture despite the apparent enclosing. Formally almost abstract, it is actually inspired by the architectural elements of the lookouts of forts, namely of the São Miguel fortress, in Luanda. Built by Paulo Dias de Novais in 1576, it held the headquarters of the Portuguese armed forces during the colonial war and today hosts the Museum of Military History. Common military lookouts allow for protected observation and the defence against enemy attacks, referring to the idea of surveillance, control and counterattack. From these, Ole’s Lookout only retains the opening of the mineral matter and an ambiguous evocation of protection, waiting and observation. In fact, all of Ole’s practice is founded precisely on the slow rhythms of attentive observation and listening, and on a refined collecting and handling of debris, rubbles and materials. In this case working with the heavy marble, which he learned to sculpt several decades ago, his Lookout also reminds us of the need for sustainable extraction of this and other minerals. Despite the apparent optical focus, the dimensions and texture of Lookout invite the whole body to the proximity of its shelter, passing through its opening not only the gaze but also the air. Large fragment of imagined architecture, ruin of ancient temple, rubble of false fortress, altar to the ancestors, window open to the passages and journeys “inside each one and each thing”. Through cinema, photography, painting, drawing and sculpture, what Ole has long embraced was the freedom to ask by making. Here, concretely, he is asking us all about the vital breath that inhabits every matter.

António Ole, Lookout, 1994, sculpture

António Ole, Lookout, 1994, sculpture

*This essay was originally published in António Ole: Matéria Vital / Vital Matter (Lisboa, Luanda: Movart, 2021), pp. 18-21.

- 1. Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley, London: University of California Press, 2001); Felwine Sarr, Afrotopia (Paris: Éditions Philippe Rey, 2016); Ruy Duarte de Carvalho, Actas da Maianga (Lisboa: Cotovia, 2003).

- 2. Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (London: Verso, 1993); Boaventura Sousa Santos, Maria Paula Meneses (Org.), Epistemologias do Sul (Coimbra: Almedina, 2010); Walter Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity. Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Antônio Bispo dos Santos, “As fronteiras entre o saber orgânico e o saber sintético”, Tecendo Redes Antirracistas: Áfricas, Brasis, Portugal (Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2019); Ailton Krenak, Ideias para Adiar o Fim do Mundo (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2019).

- 3. Ruy Duarte de Carvalho, Vou Lá Visitar Pastores (Lisboa: Cotovia, 1999).

- 4. Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, Illuminations (London: Pimlico, 1999); Krenak, Ideias para Adiar o Fim do Mundo.

- 5. Édouard Glissant, Poétique de la Relation: Poétique III (Paris: Gallimard, 1990); Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London, New York: Routledge, 1994).

- 6. Many of the least polluting peoples have been the most affected by these changes.

- 7. The creation of the Kissama Foundation took place even before the end of the war, in 1996. Although initially limited to the national park of Kissama, its activity has since been extended to other regions of the country.

- 8. Roquinaldo Ferreira, “Slave flights and runaway communities in Angola (17th-19th centuries)”, Anos 90, v. 21, n. 40 (2014), 65-90; Shana Melnysyn, Vagabond States: Boundaries and Belonging in Portuguese Angola, c. 1880-1910, PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2017.

- 9. The Church of Our Lady of the Victory dates from the same period. The construction of the fort has been attributed to Manuel Cerveira Pereira or to Dias de Novais himself, who died in Massangano in 1589.

- 10. Manuel Hermínio Monteiro et al. (org.), Rosa do Mundo – 2001 Poemas para o Futuro (Lisboa: Assírio e Alvim, 2001).