Safari in a Taxi

Without realizing, children across the world are learning and repeating words in a remote language: Swahili. In Swahili, the name of the Lion King, Simba literally means “lion”, and Rafiki means “friend”. Children from all over the world repeatedly sing Hakuna Matata, “no worries”, from the movie soundtrack. It was Hollywood that brought this peripheral language into the spotlight but as if it was its own brilliant creation, not giving it its deserved credits.

From vehicular language interposing commerce, modern Swahili counts up a large community of millions of speakers in Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and other regions of neighbouring countries.

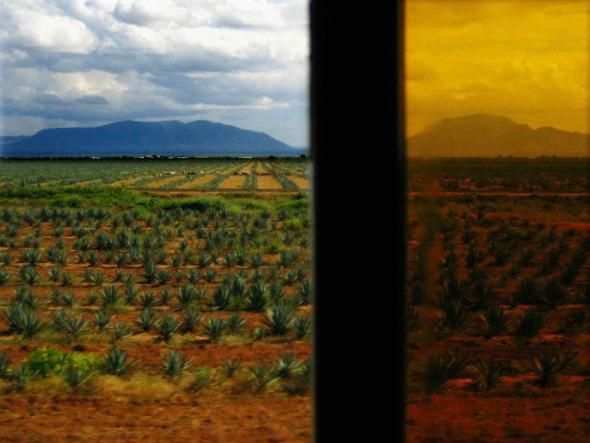

There is one particular Swahili word that would travel to integrate countless languages: safari, meaning ‘journey’. Turks, Chileans, Indonesians, Swedish, Australians and Lithuans, together with many more inhabitants of all the five continents, all understand this word, because it is part of their vocabulary, although in the stricter sense of a journey for wild life observation.

It was precisely an explorer, entrepreneur of many journeys in Asia, the Middle East and Africa, Richard Francis Burton, the responsible for the first step of the wide spreading of the word ‘safari’ when he introduced this word in English texts in the late nineteenth century. Burton, who spoke various idioms, passionately studied the cultures and languages of the places he went through. He wrote travel diaries, anthropological essays and novels. He translated “The Lusiads” into English, as well as many classics of the Arab literature, including “The One Thousand and One Nights” and the Indian book Kama Sutra.

The other’s language is our language

As Swahili exported the word ‘safari’ to the world, it reciprocally incorporated words from the English, German and Portuguese: ‘table’, meza, ‘scarf’, leso.

Languages undergo slow and permanent evolution, through an unsearchable safari, a journey with no predictable destiny that will somehow transform them.

The Darwinian theory applied to languages is not new. They are like the species; the stronger ones survive and transmit their genes. Some extinguish forever, others die, leaving its traces in new modern languages. There are remains of dead languages everywhere , not only in the manuscripts and ruins of Europe, the Middle East and India, but also in the echoes and rumours of the jungles, mountains and lake shores. As shells lying in the desert, vestiges of dead languages are alive in everybody’s conversations. ‘Taximeter’ comes from the union of ‘tax’, from the Latin word taxare – ‘to assess’, ‘evaluate’, with the Greek word metron: ‘measure’. ‘Taxi’ became the vehicle running a measured distance for a certain price. Millenniums of daily talking in various languages led to the raise of this simple word, “taxi”, recognized worldwide and naturally also incorporated in Swahili vocabulary.

“Safari” and “taxi” are two words that spread through many languages hardly suffering graphical changes.

Julius Nyerere, the first Tanzanian president, strained for the improvement of education and literacy of the population. After Tanzania’s independence in 1960, he unified the country also throughout language, turning Swahili into the official one. A more practical language than the native, as the major part of the population spoke dozens of other Bantu idioms. Declaring an official language is a much more delicate operation than defining the national flag’s colours and symbols or choosing the currency’s name, but plays a vital role in building the cohesion of a new state and its cultural identity. That was the goal of Julius Nyerere’s effort when turning Swahili into Tanzania’s national idiom. But it was not always possible for the new independent countries in post-colonial Africa to choose an official language amongst all national idioms in use. A lot of African heads of states, willing or not, have no other choice but to address their citizens in the former colonial language - whether French, English or Portuguese – because, in the absence of another common language, shared by the whole territory, privileging one of the existing national idioms, would mean diminishing all the others, fuelling regional problems.

photos by Nuno Milagre

Originally published in magazine Fugas, newspaper Público in 18/10/2008