I went there to visit artists - artistic contexts in the cameroon

One does not escape the shattered glass of the country. Everything can happen in a complex territory with over 280 spoken languages, corresponding to the same number of ethnic groups and identities. The ethnic, social, religious and environmental amalgamation and density justify why tourist brochures continuously refer to Camaroon as “Africa concentrated all in one”, where each fascinated look of the eye is followed by a contraction of the eye, where one is left without time to fully absorb the extent of beauty of each image. Life happens in grande vitesse, with the same intensity in the big cities of Douala and Yaoundé, as in Mamarom to the West, where the last ancient cities produce ceramics in mass, to be sold all around. A politically contradictory country – in the 1960’s, Cameroon was the home to a number of important activists that played a significant role in bringing about the end of colonialism. Now it still prepares its second stage of independence, under the shadow of Paul Biya’s government.

Pascale Marthine Tayou, 'Le Grand Grenier', 2008 técnica mista, vista da instalação, '50 Lune di Saturno', T2 Torino Triennale, Castello di Rivoli, Italia, Courtesy Gallery Continua, San Gimignano, Beijing, Le Moulin

Pascale Marthine Tayou, 'Le Grand Grenier', 2008 técnica mista, vista da instalação, '50 Lune di Saturno', T2 Torino Triennale, Castello di Rivoli, Italia, Courtesy Gallery Continua, San Gimignano, Beijing, Le Moulin

As most artistic productions and developments in the continent, the space of contemporary art and the work of artists shifts easily between the boundaries of the institutional and the everyday, between the domains of the professional and the non-professional. Corresponding to the idea of the bamiléké Man, known as a natural-born trader and endowed with a remarkable entrepreneurial spirit, who besides his ‘fixed job’ selling cloth in a stall at the local market, still has four taxis making some extra cash, owns a photocopy machine, cultivates his land and negotiates goats at the market, the situation of artists in absolutely versatile. Artists are ‘craftsman’ and are ‘contemporary African artists’, besides dedicating their time to other income generating activities. For the most part, the amalgamation of their artwork reveals the inevitable compromise of a mixed portfolio, between the sales which guarantee survival and an independent language.

In the Cameroon, the art circle is small. The artistic contexts of Douala, Bonendale, “Bandjoun Station” and Yaoundé are insufficient to lead to the stages and curatorial agendas of international contemporary art spheres. It is for this reason that art organisers and artists travel abroad mostly between Dakar, Paris, Amsterdam, London, New York, Johannesburg, organising events and initiatives that will bring others in, international curators and gallery owners, and consequently, Western support to development.

The artists in the diaspora have a fundamental role in projecting the name of the country into the map of contemporary art, with the potential of conjuring collateral results. In other words, when Samuel Fosso, Barthélémy Toguo or Pascale Marthine Tayou exhibit in the “Palais de Tokyo”, the “Moderna Musset”, the Miami Fair, the “Serpentine Gallery” or the São Paulo Biennale, curators and gallery owners from around the world invest in searching for new “tugous”, “fossos”, “tayous” in the field, in the hope they may repeat the phenomenon of the “Africa” effect.

Barthélèmy Toguo, The shame, 2006, Performance avec Marie Denis (FRAC, Marseille)

Barthélèmy Toguo, The shame, 2006, Performance avec Marie Denis (FRAC, Marseille) Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art Viena

Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art Viena

Jean Marc Patras Gallery

Jean Marc Patras Gallery

Ulisses and the dog

It is however with great expectations that artists who thrived abroad invest back in their country. In the Cameroonian context we can witness the creation of spaces for contestation and imagination based on local contexts, which are favoured by some artists of the diaspora, including Toguo Barthélémy, Goody Leye, Joel Mpah Doph who have set in motion social and cultural intervention projects. In a sense, similar to Ulysses returning to Ithaca, the artists return, restore ties and build houses. And like the epic, few recognize the hero on arrival, a symptom of the growth of the spaces and networks of identity construction. As Ulysses who arrives displaced and whose faithful dog Argos recognizes and confirms his identity, so are artists playing the different roles in the diaspora – migrants, emigrants, immigrants – simultaneously Ulysses and the dog.

It is in this sense that Édouard Glissant’s concept of “mondialité” holds a propositional value, competing towards the redefinition of the aesthetic, of the political, the cultural and towards a new epistemology of art. Operating within the communities of those who are aware that the wealth of the world emanates from “tout-monde” – a space contrary to the nation, to the country – and that the resulting patrimony belongs to all.

We are far from the outdated models of the nation-state and well into of a culture that is characterised by fluctuating identities, where the roles of individuals traverse, overlap, are redistributed and strengthened. And that is why, in an aesthetic plan, it makes sense to conceptualise the images and the work of artists in terms of Glissant’s proposal, benefiting from this cultural supplement, even if feeling the creative anguish in face of the triumph over former historical (post-colonial) models.

Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art Viena and the artist

Mario Mauroner Contemporary Art Viena and the artist

“The promised land” of Barthélemy Toguo

In 2001 Barthélemy Toguo presented in Nantes the “Terre Promise” installation, an airstrip overwhelmed with debris. The twelve metres filled with stones and junk disturbed the landings and takeoffs. The image of the West, individual achievement and of success rendered itself ridiculous in face of the title of the piece. In this installation, as in much of his work, Toguo spoke about the embarrassment towards mobility of people in the world. Terre Promise can be read as a satirical play of “Jerusalem” of the diaspora and its artists, an allusion to the “via sacra” of bureaucracy, of visas, papers, borders that divide, frustrated illusions, barriers to dreams, achievers that despair, habits engrained in corruption, the endless lingering for an ill-fated stamp.

To reach Bandjoun Station, in the Cameroonian West of chefferies, one makes the same mental journey of Terre Promise, but in a different order of objectives. In this case we are closer to the “Terre Promise” Toguo proposed at the Biennale of Sao Tomé, 2008, the same device, but completely covered with a thin and shiny film of aluminium. We curse the obstacles that start as early as in the country’s embassies in Europe, yet later landscapes shall wash away all pests.

Still in the international road one can see the height of the building, proudly rising in the middle of the dense vegetation of the high plateaus. Just ask for the ‘maison à étages’, in an unexpected analogy with “Petit à Petit”, a film by Jean Rouch, in which one of the characters decides to build a true ‘building’ on the banks of the River Niger. Imbued with the spirit and practice of an anthropologist, he travels to Paris to observe how people live in a ‘maison à étages,’ and there discovers the strange ways of living of a Parisian tribe.

Bandjoun Station © Barthélèmy Toguo

Bandjoun Station © Barthélèmy Toguo

Bandjoun Station: inverse roles

Bandjoun Station is a visual delight for any that first arrives. The main building has a syncretism in the composition of architectural, sculptural and decorative elements, in the way it integrates elements of local Bamileke culture (the facades portraying animals, the metal roof), contemporary forms of construction (concrete, cement, industrial coatings), a permanent build up appearance, and a strong authorial mark through the hands of the great Barthélémy Toguo. Symbols of animals and plants coexist side by side with a couple of apotropaic elements, which together protect and watch this “house of the world.”

Bandjoun Station consists of four aspects: “House,” “Visual Arts”, “Agricultural Project” and an “Educational Project”, promoting the educational, cultural, agricultural, medical and training spheres.

In one interview, B. Toguo states that Bandjoun Station looks to be “an answer to the lack of cultural projects in the continent. Increasingly, it is the West that is overwhelmingly responsible for displaying contemporary African art work as well as possessing an institutional eye over what is made. It is in this sense that I felt the need to build a place for exchange and life where international artists could come to work and show their pieces”.

The project opened its doors and to start off, an interdisciplinary team submit an agenda for a period of two years in contemporary art, dance, film, literature, anthropology and music. “The idea is to provide professional gatherings and spaces for cooperation between cultural agents from different artistic fields. We have twelve well-equipped residences, work and exhibition spaces, a library, a conference room, technical support for production and a permanent collection.”

Seven acres of land in the landscape of Bandjoun constitute a parallel strand of this artistic project. The idea is that these may function as laboratories for environmental integration and social experimentation, through coffee production, as well as other local cultures that may permit the preservation of indigenous agriculture and a sustainable community connection to the land. For Barthélémy Toguo, it is not about having a few more acres to plant, what is needed is to promote awareness of the natural wealth of the Cameroon and its use by the people. “It is a strong political act where our terrain of artists will fertilize the terrain of coffee, a critical act that amplifies the artistic act and denounces what Senghor said, the deterioration of trading conditions where export prices imposed by the West penalize and impoverish farmers in the South.”

Barthélèmy Toguo em Bandjoun Station

Barthélèmy Toguo em Bandjoun Station

In the rural landscape of Bandjoun, whose museum collection patrimony is limited to the collection of the museums of the chefferies, a new body of work will be integrated that will be available to the wider public, particularly to school audiences. Visual and sound works, names such as Roni Horn, Zwelethu Mthetwa, Fela Anikulaputi, Laurie Anderson, Benoît Fossouo, Orlan, Joel Mpah Dooh, Souleymane Sissé, Moreira, Cuco Zuarez, Balthazar Torres-Garcia, Philippe Starck, Alpha Blondy, Marcel Dzama, Marlise Bété, Peter Doïg, Carolee Schneemann, Miriam Makeba, Joachen Gerz, Alpha Blondy, Peter Rusam, Timo Dentler, among others, will constitute the main foundation which will be enlarged and placed according to regular assemblies.

The energy of Toguo and his collaborators is unstoppable to ensure the success of Badjoun Station. There, work never stops.

Night falls very early in the bamiléké highlands and music from the other side of the road from the maison d’ étages the can be heard. It’s the bard of Blanco, the whitest of all back men in Bandjoun. There is no frozen nor cold beer. It is served warm. We are in West Cameroon, they answer us.

Sementeira de café, Bandjoun Station, foto de Barthélèmy Toguo

Sementeira de café, Bandjoun Station, foto de Barthélèmy Toguo

contemporary art on the side of the road

Just off Bandjoun, a small stretch of road that takes one to Douala is occupied by scattered installations by Benoît Fossouo, an outsider artist who brings all kinds of objects from the markets of Bandjoun. For him, it is about researching on signs in nature and culture that Fossouo then develops basing himself on calligraphy (entries drawn from its name, with the colours used in the decoration of Bamiléké houses), the assemblage of objects that he finds (with access to local witchcraft), or the creation of “places” (the “Fruit Stall”, the “egg nest”, the “secret passage” to store food and equipment).

Benoît Fossouo’s installations can be considered what Jean Loup Amselle calls “self-taught primitivism”, similar to the work developed by other “African prophets”, whose best ambassador is Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (Ivory Coast). A visionary artist, Bruly Bouabré created images and an alphabet for a new “bête” writing “inspired by the cliffs of the village of Békora. The Angolan Paulo Kapela is another excellent example, whose work is characterized by a syncretism that merges the Catholic vehemence of the devout with the political icons and emblems that characterised the independence of Angola.

Today these images are part of contemporary African reality, and belong to the great collections: Pigozzi, Dia: Beacon, Sindika Dokolo, among others. The works of Bruly Bouabré and Kapela are included in important exhibitions and collections, and stand to prove the success of the “self-taught primitivism” which characterises the curatorial selections of contemporary African art. African art and the wild creative pulse still have to go hand in hand.

Benoît Fossouo, Instalation on the side of the internacional road Bandjoun-Douala

Benoît Fossouo, Instalation on the side of the internacional road Bandjoun-Douala

on the river bank of the wourri…

Bonandale is 10 km from Douala and not easy to find. Similar to the rest of the country, all paved roads dating back to “the time of the French” are crumbling day by day in the shadow of the persistent corruption of the police. To find the MTN residency one must ask for the “village d’artistes” and sacrifice the suspension of the car before reaching the banks of the Wourri River. The landscape abruptly changes. Here, there are only a few local inhabitants, the fishermen who drift in canoes (pirogas) loaded with the shrimp that went on to baptize the country, and a group of artists.

workshop, MTN Foundation, Bonendale

workshop, MTN Foundation, Bonendale

It was Joël Mpah Dooh the first who decided to leave the chaos of Douala to “settle in a place closer to nature”. Currently, besides Joël, Goody Leye, Louise Epée, Salifou Lindou, Jules Wokam have joined, buying houses and land. The “village d’artistes” is an informal network of artistic collaboration which integrates the individual work of each artist as well as their cultural projects, such as the MTN Foundation residency and the “Art Bakery” project, as a means of protest and refusal towards the modus operandi and approach to working and living in the city. “The arrival of the artists in this place were real ethical and political responses”, we are told by Joël while he shows us the spaces of the TN Foundation residency, a telecommunications multinational with a very strong presence in the Middle East as well as in the African continent: from the Ivory Coast all the way to South Africa, where it is the official sponsor of the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

Joël Mpah Dooh Dessins, Plexiglass, ferro

Joël Mpah Dooh Dessins, Plexiglass, ferro ArtBakery Bonendale

ArtBakery Bonendale

telephone credit MTN, Bandjoun,

telephone credit MTN, Bandjoun,

young artists MTN Foundation

Today is the day to present the outcomes of the residency, and among the green and the silence, a large group of people gather around in a circle. The young resident artist Bruno Nsecke received 1.000.000 F. “A very prestigious prize, specially when you are only 25 and everyone is looking around from one side to the other searching for something”, we are told by Mpah Dooh, “and that is why all timings are strictly respected and obeyed with MTN (…) there can be no disorder, no delays, or we loose the support and sponsorship”, he adds. Established in 2006, the MTN residency promotes a wider interaction between the artists and the geographical environment, looking for the necessary forms of production to implement individual projects. It also allows for the display of each project resulting from the residencies in Douala, contributing to the promotion of emerging art in the Cameroon.

After the presentation, the conversation livens up and moves towards the topic of African biennales. What is Joël’s opinion about the inclusion of these young artists in the African and international circuit, Dakar, Johannesburg, Cairo, Luanda, São Paulo, USA, China? Joël Mpah Dooh appears to be uninterested and justifies: “We had the Revue Noire, in the 90’s which launched several names into the market, it was a general euphoria that transformed the way we felt as artists, and African artists, and now we complain about the necessity for specialised schools that strengthen skills, capacity and training, because for years all we were interested was in responding to the market”.

It is on the basis of this reflection that the MTN Foundation residency Project aims to continue to develop skills and training, looking to fill the voids of the Cameroonian education system lacking any type of higher education in the artistic field. In addition, it will soon invest in opening up residencies for young foreign artists, alongside with Cameroonian artists.

a workshop for creation connected with the west

“Art Bakery” is most dedicated to its ‘artist residency’ component. Operating since 2003, and coordinated by Goody Leye, the project takes place in a colonial style house in the urban and rural dispersed fabric of Bonendale. The site reads: “an oasis of creativity”, “a convivial space where art is made and discussed throughout the day,” and “a physical and mental space where artist is questioned, exchanged, experienced”. For G. Leye “it is reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Art Factory, only with a more sensorial aspect to it, because the idea is that everyone can roll up their sleeves and work the materials we have available.”

The “Art Bakery” projects are posted on the exterior walls of the building: training seminaries for critics and art historians, educational services to Bonendale’s primary schools, masterclasses, a audio-visual post-production studio, etc. Estella Mbulli works here and explains each project with great detail, focusing on what matters most: Exit Tour in 2006, where seven artists travelled through seven countries in West Africa, seeking informal spaces to engage with artistic projects made during the trip. The purpose of Exit Tour was to arrive in Dakar for the opening of the Biennale, and “interrogate the trip as a means of aesthetic drifting,” he explains.

Albeit tiny, “Art Bakery” includes a library that provides the best editions of the Universal History of Art, Gombrich’s critiques, Danto, Krauss, the catalogues of Les Magiciens de la Terre, Okwui Enzor’s Documenta, as well as some issues of ArtForum magazine. Despite the breadth of literature, one does not quite understand the extent of interest or the existence of local readers on topics such as primitivism, diaspora, post-colonialism, or the latest acquisitions of the Pigozzi collection. Some catalogues are plastic-coated, “These were donated by the French Embassy in Yaounde,” we are told by Estella, while showing the rest of the space.

Largely supported by the RAIN Artist’s Initiative Network programme, from the Rijksakademie (Amsterdam) which promotes cultural exchanges between Western and non-Western artists, the Art Bakery has been able to find specific funds to its projects: funding from the Dutch lottery – the DOEN Foundation, the Art Moves Africa (AMA) programme that aims at facilitating cultural and artistic exchanges throughout the African continent, as well as the LAAB, a “studio programme” that allows artists from Basel to travel during significant amounts of time to other continents.

a journey to the extremities of a city

The 10 km’s that separate Bonendale from Douala are done in very slow and uncertain motion. Cars attempt to avoid the large holes of a road scattered with stagnant waters. The result is an overwhelming number of what resemble metal boxes amalgamated at the entrance of the city.

Joseph Sumégné, La Nouvelle Liberté Douala (Deido)

Joseph Sumégné, La Nouvelle Liberté Douala (Deido)

The large 12 metre sculpture “La Nouvelle Liberté”, by the artist Joseph Sumégné, welcomes those arriving in Douala, with one arm raised high. While an ironic analogy may situate it closer to the Statue of Liberty, and indeed, many people do travel to Douala attempting their luck, the truth is that the city is a dim “el dourado” filled with misery, disease, and the most primary ways of life, already described early in the century by Louis Ferdinand Céline. In the energy of a newly conquered colonialism, the French writer felt the space and freedom of action, but does not refrain from characterising Douala as the sick “Fort Gono” from Voyage au Bout de la Nuit, a metaphor-city of venereal diseases, delusions and sexual encounters between white men and black women.

Currently, Douala is an extraordinarily dynamic city and the stage of constant spatial, social, relational, and political changes. Like their African counterparts, especially in central Africa, one of the most striking features is certainly the development of social and economic fabric. The formal and informal city coexist, setting in motion movement that constantly arranges and mixes ethnicities, cultures, nationalities and religions. To some extent, Douala falls under the type of cities of the South, spoken about by Rem Koolhaas, capable of proposing new urban models, and new ways of organizing the informal sector. A city in transit in its forms and content, allowing us to experience life in a shifting world, a “vernacular cosmopolitanism” (Homi Bhabha), in and out of Cameroon and Africa.

La Pagode (Manga Bell's family palace, Douala-Bonanjo)

La Pagode (Manga Bell's family palace, Douala-Bonanjo)

the city as a laboratory: Doual’art

It is from the city, and particularly of an understanding of the city as a living organism, that the Doul’art project was conceived, contemporary art centre, defined as a research lab on urban matters.

We are welcomed by Didier Schaub, the artistic director who shows us the space while speaking about the history of the organization he co-runs with Marilyn Douala Bell.

“The space was an old cinema we recovered in 1991 when we started, and today it is a gallery hosting a number of initiatives.” Some of the ongoing activities of the organization include exhibitions, workshops, educational activities and training activities. On display is an installation of the Moroccan artist Younis Rahmouni, curated by Abdellah Karroum, but preparations are already underway for the next pieces by the French duo of artists of the Art Orienté Objet.

The type of projects of this organisation relate to what we could call “social engineering”, focusing on the actions of the neighbourhoods of Douala and establishing projects with various communities. “It was the long-term experience in the neighbourhoods of Douala that led to the idea of the main project we are now dedicated to, the Salon Urbain”, we are told by Didier Shaub.

LDS Salon Urbain de Douala is a biennial presentation of projects of public art that has been undertaken by the organization Doual’art and is preceded by a curatorial meeting.

Arts et Urbis will bring some curatorial reflection to Douala, through names such as Arno van Roosmalen, Ngoné Fall, Simon Njami, Jérôme Sans, Edgar Pieterse, or the Cameroonian artist Pascale Marthine Tayou, and will also serve to discuss the city and its relationship to water, the main concept of SUD 2010.

Hervé Yemguem is one of the artists who will perform a project for SUD in 2010. He is an “home artist”, and represents the younger generation of Cameroonian artists. He has already started preparing “Mots Écrits” in collaboration with young rappers in the neighbourhood of New Bell. Paulin Tchuenbou, producer of the activities of doual’art and fine connoisseur of the city takes us there.

Didier Schaub, artistic director of Doual’art, Douala (Bonanjo)

Didier Schaub, artistic director of Doual’art, Douala (Bonanjo)

It’s New – Bell, camarade!!

“New Bell” is the district with the largest number of immigrants in the city as well as the most conflicting. Muslims who pray facing Mecca coexist alongside groups of men who are most interest in partying, between rounds of beers. The territory is marked millimetrically and youth groups dominate the streets and its intersections, waiting for customers to make their daily share of money. You hear the “Pst, Pst” everywhere, from boys in moto-taxis and in “pousse-pousse,” wheelbarrows carrying goods from one place to another. A motorcycle trip costs 50 cents, and can be negotiated according to distance.

We arrive at Hervé Yamguem’s house. Two divisions that also serve as an open workshop to the New Bell neighbourhood. The poet and artist is working on the theme of “water” for the Salon Urbaine de Douala (LDS). The rhythms of the young rappers from New Bell help the work and the party “C’est le sauvetage./ Ils fanam de gauche à droite./ Le combat est rude./ L’eau est un miroir du monde”. Moctomoflar, the stage name of the young man just arriving, tells us that “the water here in the neighbourhood is very precious. Sometimes we have to attend to the fact that Muslims spend water to wash five times a day, while the mums have no water.”

Until the SUD 2010, many steps will emerge. For now, we prepare the general presentation of the projects in each district with rest of the artists, Salifou Lindo, Hervé Youmbi, Jules Wokam, Julie Courcelle and Achille Ka.

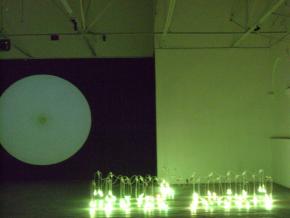

Younès Rahmoun instalation in Doual’art, Douala

Younès Rahmoun instalation in Doual’art, Douala

During the month I visited Cameroon, several important events were highlighted in the media. In Africa, the conflict escalated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the death of the South African singer and human rights activist Miriam Makeba was announced; internationally, the leaders of the largest economic powers in the world met to define a strategic plan in response to the financial crisis, and Barack Obama won the US elections. This concise international agenda, enough only to include the main headlines, is symptomatic of the image of Africa circulated particularly around Western spheres. Whether we concentrate on the inherent nature of each of the events listed, or we choose to see them as a whole, Africa is portrayed as an over-determined image. In other words, a place capable of shaping the abundance of circulating discourses, the terms and labels for the continent and the situations of traumatic nature.

The widespread geography that characterises Africa both internal and externally, the continent remains a space of ambivalence that still polarizes fundamental issues as human rights, racial equality, apartheid, subordination, hybridization, mixing, the displacement of people and cultures. During the American elections for example, Barack Obama’s victory had once again at the centre of the debate issues of race and class, from the Cultural Studies of the 1970s. The Indian historian Sarat Maharaj accurately suggests and alerts us to the fact that we are falling into the “spectacle of discourse” .

Curators and organisers of cultural initiatives with significant visibility, which usually feed the typical discourse, invert this order. ‘Reflexive pauses’ and ‘emptiness’ are now promoted as is the case of the last edition of the São Paulo Biennale, in a firm awareness of expanding and building upon these principles, in search of new territories.

But is it possible to formalise and legitimise these statements which derive mostly from critical agents, and along with them, impose to economic agents a quasi-utopia, in a market that even while in crisis, has in its works of art, the symbolic legitimization of the highest purchasing power? If all spheres of life are threatened by the certainties that the current Western system has reached, the artistic field constitutes no exception to this. Maybe, in a near future, loosened guiding lines may arise in spaces beyond the macro-scale, the specificities may be invested in (in the case of the biennale model), and forms of creation and production that amplify experience may be called upon.

Published in Arte Capital