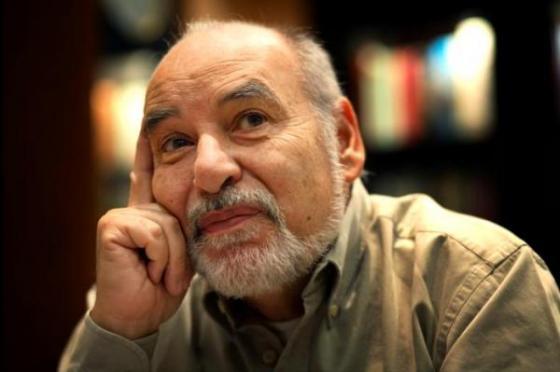

Interview with Tahar Ben Jelloun, “A book about love can be political”

He is Moroccan and French at the same time. He writes in French and nowadays looks at the social and cultural transformations in the countries of the Arab Spring. And expects the new France will adopt a different attitude relating to dictatorships.

With his two passports and the belief in the writer’s role of “criticizing, denunciating, and intervening”, Tahar Ben Jelloun was at Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation at the end of June for a conference in which his aim was “explaining the Arab Spring”. Invited to participate in the program Next Future, which this year is focused on the revolting North of Africa, Ben Jelloun came also to present the Portuguese translation of his 1995 book “Le premier amour est toujour le dernier” (“O primeiro amor é sempre o último”, now published by Quidnovi editor). He talked with us about Islamists that “took advantage from the rebellions”, about women of his birth country, Morocco, that benefit from new laws to “regain their liberties”, and about his expectations with the “new France”, the country he elected as his own.

You have lived in France for 40 years. Ten years ago, you felt the impact of assaults. Last year, that of the Arab revolutions. Do this side and that side know each other better or worse today?

I think that this conception East-West is very fluid. If we think about Europe, or France, we are in the West, but there are a lot of people from Maghreb. What has happened in the last ten years, which is very worrying, is the form how Europeans have perceived Islam. The exaggeration, the fear. This helped the extreme right wing winning good results. This islamophobia is based upon a little minority of French or immigrants, they are very few, who manipulate Islam. The reaction has been disproportionate. The extreme right and the right played with fears, moving from small facts. The result of this is that Islam doesn’t have a good reputation. And this happened also in such countries as Norway and Sweden, which really don’t have a problem of racism.

Did revolutions create a new, but in the same way distorted, image?

The Arab revolutions created a good image. People told: “They are wonderful, they fight for democracy, for freedom”. But afterwards Islamists took advantage from these revolutions and this, of course, changed again the perception, disconcerting again those who are from the outside.

Was not to be awaited that Islamist movements, persecuted by the knocked over dictatorships, would have gained a disproportionate political space? At least in the first phase?

Islamism is a drift from normal Islam. It is a deviancy that has become extremism and which threats Muslims. There are various forms of practicing Islam. In Morocco, for example, there is a calm Islam, which is not threatening. In Egypt and Tunisia, Salafis attack pairs of lovers or cafes that serve alcohol. This is a threat, first of all, for Muslims.

Are Europeans able to see that?

They must make a great effort. We try to explain, but it is very difficult. I try doing it and write about the Arab Spring. A few days ago, for example, I published a text in the newspaper “Le Monde”, but those who read are a minority, they are intellectuals. It is true that Islamists usurped the revolutions, but on the roads of Tunisia or of Egypt democrats and women, too, are continuing the fight.

There is a resistance of the secular society. In Tunisia, [Habib] Bourguiba [the president knocked over by Ben Ali in 1987] gave women the most liberal status of the whole Arab world. Now they don’t want to lose this status. And Islamists don’t want them to maintain it.

The crucial problem of Islamism is sexuality. The visceral fear of an Islamist man is that someone sees his woman or touches her. So they decide to hide her. And there are women that accept this, which is completely unintelligible.

In the manifestations there are lay and religious women.

Yes. At the same time, the contemporary, modern woman wants to participate in life and has political conscience. In Morocco, there are women who use the veil and work like the others. It is a matter of degree, it is sometimes a reaction against the West, which considers women as objects and passes this idea through the cinema and the television. There are women that, even if they are not fanatic, react against that. They don’t want to show themselves in this way. There is a part of morality in Islamism.

In France, for example, there are laws against the use of some kinds of veil: isn’t there the risk for them to be counterproductive?

In France there is everything, the women who use the integral veil are few hundreds, there are many who don’t cover themselves or use a veil to cover the hair. And you can notice this moralizer point of view. We have arrived at a moment in which we must choose. It isn’t possible to want to live in a secular State and at the same time to exhibit religious signals. The vote against burqa [which covers the whole body, the hair and the face] is normal in a secular society. If someone wants to work in the public administration, it is normal that he or she cannot cover his/her face. But when there are such laws as these, as in Belgium or Spain, approved by municipalities where almost there are no Muslim women at all? Sometimes to prohibit the veil in state schools, for example, in some cases in countries where catholic symbols are exhibited. Those who use the burqa in Europe are a small minority. If we were born in a society that fought for secularization… I think that the debate about the veil raised the matter of secularization in a global sense in countries such as Spain, Italy, or Holland.

In Morocco a series of openings is occurring. Has women’s value approximated to men’s value?

It started changing well before the Arab Spring. The status is not the ideal one and is not everything, but the transformation occurred corresponds to a modernization of society. Moreover, women have always worked more than men in Morocco.

Today, the rights arrive at the political stage. The State says: “Let’s give this right to women.” Divorce, for example, or laws that protect mothers. But society doesn’t change by decree.

Morocco, where there has been freedom of demonstration for many years, didn’t experience a revolution, but saw the birth of a new protest movement. Was it important for accelerating changes?

The February 20 Movement has been very important. People demonstrate a lot in Morocco, this is normal and is continuing. There was a big demonstration in Casablanca a month ago. Morocco is playing the card of democracy. It isn’t a democracy yet, but it has an opposition that expresses itself, that criticizes the government. Everything’s moving. But it isn’t everything alright.

Was last year a turning point? Some members of the Unemployed Graduates say that February 20 already changed the language, the way in which monarchy is looked at.

Sure. We aren’t sleeping. We don’t accept everything. The Unemployed Graduates movement is many years old. And February 20 is very important for accounting on the disfunctionality of the country administration, an economy practicing a wild capitalism, a country that leaves a lot to be desired for what concerns social rights.

You are Moroccan and French, and a writer who intervenes in politics. Does being in the middle of the path allow building bridges? Does it help understanding and having others understand?

I have two passports, one Moroccan and the other one French. As a writer, I am sensitive about my own political experience and recognize my values in my work. Not all writers are like that, but I am critical and open-eyed, it is the writer’s role. The writer is that who criticizes, who denounces, who explains, who intervenes. I have a history; I began writing in the ‘60s. What made me write was injustice, and the violence of repression. I chose my literary universe; the citizen already existed.

In your books there are incomprehension and impossibility of sharing between men and women. In the book you’ve come to present there are love affaires, sex, contradictions, good religious that aren’t so.

“Le premier amour” [“The first love”] is a book we read with pleasure, it tells strange and nice stories. But in it, too, there is a vision of men and women’s role in the Mediterranean countries. My own vision.

I imagine situations, think up stories, but these translate my own world visions. And it’s for this reason that even a book about love can be political.

You will write love stories very different from these: will you be able to imagine them occurring in Morocco?

Things evolve normally. Now, in Morocco, there are many more divorces than before because the new laws admit it. They’ve been a way for women to regain their freedom.

The writer that I am looks at this transformation happening, for a country where today they talk about paedophilia, incest, mistreatments. All these realities already existed, but today we know they exist. Moroccan civil society is also extraordinary, there are movements that were born in the latest years to support lonely women; there is an association for the fight against AIDS, which explains what needs to be explained openly. This would be impossible in Algeria or in Saudi Arabia. I see positive elements, but I am still and always critical.

You’ve come to “explain the Arab Spring” at the Gulbenkian’s Foundation. Is it possible to look forward in such a fluid moment as this?

I’ll try to talk about the future of these Arab Springs. At present time, they have been imprisoned by Islamism or, in Syria’s case, by a mad regime. But there are hypothesis that can be designed.

Can a conference influence the way people look at the world? Do you feel this responsibility?

The writer must accept the fact that he talks and talks and nothing happens. Literature has limits; we cannot change anything with books or with a conference. I do what I do without many illusions. Of course, there is sometimes someone in the audience that in the end come to talk with us and tell: “Ah, so it is!” I am not a prophet. But I am patient and always do an effort; I put myself in the place of a baby who needs explanation. And I apply this principle with a lot of modesty.

France (and the rest of Europe, as well as USA) had a lot of difficulties leading with rebellions, first of all in Tunisia, afterwards in Egypt, and in Libya. Did you expect a different approach?

France and other European countries were guilty of having supported these dictatorships in the name of their own economic interests while so many democrats of these countries, writers, and journalists denunciated their horrors. But I expect a different attitude from the new France. In spite of the crisis, of History that overwhelms us all, we can claim a socialist government for being much more understanding with the world, with these peoples who fight and suffer. Before, in [Jacques] Chirac and [Nicolas] Sarkozy’s times, we had ministries who went on holiday paid by the Moroccans, by the Tunisians.

When silence was bought, we cannot expect much.

Do you really believe in a different attitude now?

[François] Hollande can be trusted. He has to confront with the whole weight of the economic crisis, that overwhelms us all in the world. But, at least, for what concerns international politics, we can expect a greater earnestness from this government. We can demand it to be really different relating to a Sarkozy or Chirac’s government. This is sure.

This article was originally published in the Portuguese newspaper Público on June 2012