How The Zebra Got Its Stripes

“Whoever does not know from where they come

Does not know where they are

Nor where they are going”

Lília Momplé

I get asked where I’m from nearly every time I meet someone. To my answer (Mozambique) I often get puzzled looks leading to the next comment: I don’t look Mozambican; to which I usually reply that I agree, I don’t.

I get asked where I’m from nearly every time I meet someone. To my answer (Mozambique) I often get puzzled looks leading to the next comment: I don’t look Mozambican; to which I usually reply that I agree, I don’t.

Being very specific can become tiring, and it breaks the magic of meeting new people. It also prevents them feeling they have offended someone right off. People are generally just curious to know the why of things. Of course, their real question aims at finding out how come I’m white and an African.

Why am I not black. Or rather, how did I end up a Mozambican?

These questions about identity are normal. They come up more often when I’m not in Mozambique due to (I assume) lack of historical knowledge. But what does a Mozambican look like?

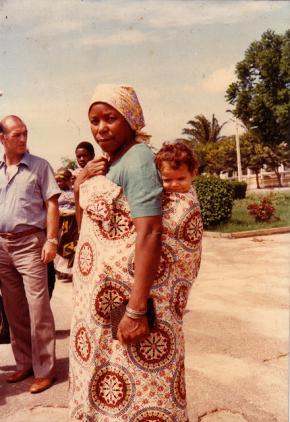

Mozambique, as a nation, didn’t exist until 1975. It was then it was born, a carrier of other nations within its borders, of ethnicities as varied as Shangana, Makonde, descendants from Swahili and Arabs from the North, descendants from Goan, Pakistani, Portuguese, Ronga and so on. With that new country came a new nationality — Mozambican. One couldn’t earn that title before 1975. From then on, people could finally own a Mozambican passport. We were now a sovereign state with independent citizens of all sorts of backgrounds. That’s one thing that made us Mozambican.

Now, when it comes to being African and an artist, the game doesn’t get any easier.

This year, it was suggested that I take part in a symposium/book fair in Sweden, in the African comics category. But, because I was not producing “African comics” or any comics about Africa, it was not interesting for the organizer to have me there, even if to show what Africa is not all about. The organizer initially said they lacked the budget to invite me, so I offered to go on my own expenses. No deal was cut. Was I perhaps simply not African enough? Would I be invited if my work (the very same one) was to have been produced by a Macua, Yoruba or an Igbo? Maybe. I would probably have been invited too, had I been producing African comics, however that category may be defined (I’m genuinely curious to know). But, being an African and white, and not even producing something visibly African, doesn’t entitle me to play the game.

With regard to literature, Mia Couto says:

“… others try to place the authentically African in the rural tradition. As if the modernity which Africans are inventing in the urban areas wasn’t itself equally African. That restricted vision of what genuine is, possibly, one of the main causes to explain the suspicion with which literature produced in Africa is regarded. Literature is on the side of modernity. And we lose “identity” if we cross the boundary of the traditional: that’s what the hunters of racial and ethnic virginity say.”

Imagine Hollywood making films only about Americans: Martha Washington, Babe Ruth, Maya Angelou, Charles Manson or Langston Hughes. If that was the case, American film directors wouldn’t have been ‘allowed’ to make Letters from Iwo Jima, Blood Diamonds, or The Last Emperor. These films are considered American films. No question about that.

ilustração de rui tenreiroSo, why the curfew on African artists? Why should we have to submit to a rule which has nothing to do with the reality of our country? African artists should create films, books, paintings, installations or theatre using their own background and personal experiences as a driving force. If the outcome is something to do with African societies, fine; and if not, fine too. The artists will be no less African because of that. They should simply be themselves, do their best, and not try and fit the caricature of what we, as African artists, hould be doing.†

ilustração de rui tenreiroSo, why the curfew on African artists? Why should we have to submit to a rule which has nothing to do with the reality of our country? African artists should create films, books, paintings, installations or theatre using their own background and personal experiences as a driving force. If the outcome is something to do with African societies, fine; and if not, fine too. The artists will be no less African because of that. They should simply be themselves, do their best, and not try and fit the caricature of what we, as African artists, hould be doing.†

Again, I couldn’t agree more with Mia Couto, when he says:

“It is demanded of an African writer what is not demanded of a European or American writer. Proofs of authenticity are demanded. It is questioned to what point is he/she ethnically genuine. No one questions just how much José Saramago represents the culture of Lusitanian roots. It’s irrelevant to know whether James Joyce corresponds to the ethnic standards of this or that european ethnicity. Why must African authors display such cultural passports? This happens when it is thought of these African authors’ productions as something within the anthropologic or ethnographic domain. What they are producing isn’t literature but a transgression of what is taken as traditionally African.”

While I was doing my Masters I felt pressured to work with an Africa theme.

I eventually had to defend my reasons for deciding not to debate Mozambique in my work. Africa and Mozambique is a large swimming pool and I don’t yet want to dive into it. But still, the pressure to do it followed me to my first presentation. I was asked why I had given up the Mozambique theme, even months after I’d been working towards another goal. It was also asked why it was that I chose to make a story in which everything was so European, so Victorian in fact. Why wasn’t the main protagonist a black man or woman. I expect and welcome questions of course, but I also felt a general underlying sentiment that, as an African artist, I was supposed to be working with something that would be African in some way.

I see Western books and comics about Africa being made all the time, but it doesn’t seem to be possible for an African to come out, make a book about Australia, and still be considered African. No. The artwork or story must be set in Africa (or at least be created by a black African person). If an African has to be black in order to earn the right to make works which are not African in theme, then a white African can REALLY not deal with themes which are not African. This refusal to play the game will result in the artist not being considered really African. But whose African reality is this? Ours or another?

ilustração de rui tenreiroNot only this, some of the artworks which are expected of African artists often require the African artist to create works that depict the African reality, and not some other personal, crazy, acid-trip reality which does not comply to at least some of the Western expectations of us. Those romantic visions have come to include images of an Africa-turned-cosmopolitan and Nollywood. In several variants of the Western fantasy, Africans usually dance well, are happy people, have charismatic and ruthless dictators, high libido, and can make great gadgets out of trash.

ilustração de rui tenreiroNot only this, some of the artworks which are expected of African artists often require the African artist to create works that depict the African reality, and not some other personal, crazy, acid-trip reality which does not comply to at least some of the Western expectations of us. Those romantic visions have come to include images of an Africa-turned-cosmopolitan and Nollywood. In several variants of the Western fantasy, Africans usually dance well, are happy people, have charismatic and ruthless dictators, high libido, and can make great gadgets out of trash.

On stereotypes, Chinua Achebe says:

“Stereotypes are not necessarily malicious. They may be well-meaning and even friendly. But in every case they show a carelessness or laziness or indifference of attitude that implies that the object of our categorization is not worth the trouble of individual assessment.”

I have also experienced prejudice towards expectations of Africanity in Africa, by Africans. Once, an established South African artist who deals with questions of identity in his own work and comics, asked me why it was that I wasn’t producing African comics, or about Africa, or Mozambique. I was then told that, considering this handicap, it would be hard for me to be able to take part in an African comics festival, as an African artist. The cliché also inhabits our backyard.

I have no doubts in my mind what I am, — as a person, and as an artist. I’m proud of being a white Mozambican. I’m happy not to fit the cliché, and I’ve known all along where I stand. It doesn’t take long to see that I’m the minority. I’ve been some sort of minority everywhere I lived — in Mozambique as a white person, and everywhere else as an outsider. And the minority of minorities: everywhere else as a white African.

———————————————————————————

* “É com lúcida frontalidade, que o historiador congolês Elikia M´Bokolo, numa

entrevista reproduzida pelo semanário Savana (23/02/2007), reconhece que não existe propriamente uma intelligentsia real, em Moçambique, capaz de, à semelhança de outros países africanos como o Senegal, o Gana, o Quénia e a Nigéria, debater os interesses do país, tomar posições e fazer avançar as suas resoluções.”

— Fátima Mendonça in “Ser Nacional vs. Ser Universal, Literaturas emergentes,

identidades e cânone” (Literatura moçambicana: as dobras da escrita.

Maputo:Ndjira, 2010)

† “African intellectuals* needn’t feel embarrassed. They don’t need to correspond to

the image which european myths made of them. They don’t need artifices or fetishes to be[come] african. They’re african just as they are, urban, of miscegenated and mixed soul, because Africa has plain right to modernity, it has the right to assume the miscegenations which it initiated, and which make it more diverse and, therefore, richer.” — Mia Couto

Other sources:

— Mia Couto, Intervenção na cerimónia de atribuição do Prémio Internacional dos 12 Melhores Romances de África, Cape Town, Julho de 2002) — Publicado em Pensatempos, editorial Caminho, 2005. {Link}

— Chinua Achebe, foreword to The Anchor Book of Modern African Stories (1994, Anchor Books, edited by Nadezda Obradovic).