Diego Rivera's Portuguese ancestry

The Countess, the Aeronaut, and Diego

When the Acosta, a family of Portuguese Jews, arrived in Mexico in the early 19th century, they began the paternal lineage of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. A memory that the artist would claim throughout his life.

It is said in Mexico that good life stories are passionate. They are happy and painful, they tie and untie blind knots in the throat, like a harsh swallow of cheap tequila.

We set the tone and enter one of the taciturn taverns of the city of Guanajuato - the so-called “cantinas”, where personal tales are distilled as the glasses advance. Rough stone walls in the half-light, damp breath. In my head, Chavela Vargas sings “Tú me acostumbraste.” It’s night and it’s raining softly outside.

With a toast, we seal the moment. And we tell a secret life story.

Statue of the muralist next to the house where he was born, in Guanajuato, and that today houses the Diego Rivera Museum House

Statue of the muralist next to the house where he was born, in Guanajuato, and that today houses the Diego Rivera Museum House

It was in the last years of the 19th century, on this canvas in the style of colonial Mexico - a stereotype still very much alive - that the childhood and adolescence of Diego Rivera were drawn. The muralist and painter (simply “Diego” to Mexicans) was born in 1886 on the top floor of an old house in Guanajuato. Number 80 of Positos Street, where 43 years ago the Casa Museo Diego Rivera was installed.

Controversial, temperamental, huge, and disproportionate, the frog-eyed, frog-handed Diego was the husband and lover of Frida Kahlo (see box) and one of the most iconic Mexican artists in the world.

A thousand times the muralist’s life has been portrayed, but there is a side of him that is virtually unknown, even in Mexico. There are no official documents, the story has murky parts and even some contradictions. But both the artist and the old generations of the family remember: Diego Rivera descends from Portuguese Jews, the Acosta, who arrived in Mexico at the beginning of the 19th century.

“[My ancestors were] Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, and - I am proud to say it - Jewish,” he declared at a press conference in Mexico City in 1952. “I remember above all (…) my grandmother - she was a Portuguese Jewess by the name of Inés Acosta,” he reinforced, on the other hand, in an interview with the American photographer Marcel Sternberger.

Inés Acosta, the grandmother who “observed Shabbat,” would be a constant reminder in the life of the grandson-artist, making her presence felt whenever Diego wanted to claim his ancestral Jewish heritage.

Inés Acosta, Diego Rivera's paternal grandmother, was descended from a Portuguese family that emigrated to Mexico around 1820Inés and the Silver Crown

Inés Acosta, Diego Rivera's paternal grandmother, was descended from a Portuguese family that emigrated to Mexico around 1820Inés and the Silver Crown

At the top of a narrow stone staircase that climbs the Beco das Almas in Guanajuato, an airy plaza emerges, like a breather. On the left side, framed by two trees, we find the old villa where the Portuguese Acosta family settled when they arrived in Guanajuato, “in 1822 or 1823,” according to the Jewish-Castilian Encyclopedia, cited in an article by Diego Rivera’s personal secretary, Raquel Tibol. The pink-mortar building now appears uninhabited. We can’t find the doorbell. We knock on the door once, twice. No one answers. We don’t insist.

Just like the house, the history of the Acosta family is spectral and silent. When the family arrived in Mexico, “Portuguese immigration to the country, traditionally made up of Jewish converts, was already very rare,” historian Alicia Gojman tells Notícias Magazine. “The great autos-da-fé that took place here in the 17th century marked the end of the mass arrival of Portuguese people”, contextualizes the researcher from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Also, Diego Rivera’s daughter, Guadalupe Rivera Marín no longer has “any memories” about the origin of the Acosta family. “They were very old families, I don’t remember hearing my father say anything about it,” she tells NM in a brief phone conversation.

It is in Diego’s biographies that at least his grandmother Inés gains some form. We know, therefore, that she was born in the house of the “Acosta family of Portuguese origin” around 1825 (and not in Portugal, as Diego said). She was fatherless and lived in the small square until her marriage to Anastasio de la Rivera, also of Jewish origin and a native of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg, Russia).

Acosta' house in GuanajuatoWhen they tied the knot in 1842, Inés was 17 and Anastasio was 50: “A young man of twenty could not have been a better lover,” the young woman is said to have said in the only sentence known to her, according to author Patrick Marham in “Dreaming with Eyes Open. The couple had nine children, including Diego Rivera’s father.

Acosta' house in GuanajuatoWhen they tied the knot in 1842, Inés was 17 and Anastasio was 50: “A young man of twenty could not have been a better lover,” the young woman is said to have said in the only sentence known to her, according to author Patrick Marham in “Dreaming with Eyes Open. The couple had nine children, including Diego Rivera’s father.

In “Two Diegos, Two Riveras,” one of the muralist’s great aunts recovers one of the few remaining first-hand memories of Inés. Aurora Alcocer tells us that one day her “abuelito” Anastasio discovered a silver vein in the Asunción mine, of which he was co-owner. “It was a load so big that eleven men with their arms outstretched could not embrace it.” Euphoric, the old Anastasio then crowned his wife Inés: “You will be the countess or marquise of Asunción de la Navarra!”

The ad hoc noble title was short-lived silver. A few years later, the mine flooded, and the family was in financial straits. Two hours from the city of Guanajuato, in the Santa Rosa Mountains, Asunción is now part of the “adventure tourism” itinerary of the region’s ghost mines.

Uncle Benito the Flying Knight

Although Inés is the figure most remembered by the old generations of the Rivera family, a commemorative plaque in the Acosta home celebrates, “Engineer Benito León Acosta, the first Mexican aeronaut, was born in this house.”

The milestone is important for Mexican history. Diego’s great-uncle was the first person to fly in the country’s skies, in 1842. “He brought the first hot air balloon (…), he had learned this art in France and Holland,” reports author Loló de la Torriente in “Memory and Reason of Diego Rivera.”

At that time, Benito was a true national hero. The then President of the Republic, Santa Anna, named him Knight of the Order of Guadalupe and granted him the exclusivity to fly in Mexico for three years. Even today, the pioneering aeronaut is honored at the Leon Hot Air Balloon Festival, the third largest event of its kind in the world, which takes to the skies every year in this city 60 kilometers from Guanajuato.

The achievements of Inés’s uncle are well known, but the plaque commemorating the old house ends up changing things. The inscription also says that the aeronaut was born in this manor house on “April 11, 1819,” that is, three or four years before his own family arrived in Mexico. In her memoir “Dois Diegos Dois Riveras,” the muralist’s daughter Guadalupe shuffles the cards even more: the plaque “says he is from Guanajuato, but we know he came from Portugal.

Contradiction? Maybe not. Historian Alicia Gojman presents NM with a hypothesis: “At the time this family arrived, Mexico had just become independent, and the memory of the Inquisition was still quite fresh. There were many people who arrived and did not declare themselves Jewish.” In the case of Benito Acosta, the scholar raises the possibility of a “reinvention of identity” as a ploy to escape possible antisemitic threats.

In search of clues, NM asked the Guanajuato Historical Archives for access to the city’s 19th-century birth certificates. However, the oldest record dates to 1869, fifty years after the Acosta biographical crossroads. The mystery remains.

Memory, Reality and Fable

The memories of the Acosta times are, in Diego, loose fragments. The artist himself once wrote: “My childhood memories are mostly visual. They resemble photographs of my life, with intervals of time between them, and with no immediate connection to each other.” Like flashes.

In the prologue to the biography “Encounters with Diego Rivera,” editor Jaime Labastida notes that the Mexican artist had “a tendency to mystify more and more” the memories as they “moved away in time.” Also, Guadalupe, Diego’s daughter, writes in the very first line of this work: “My father invented everything, every day.”

It is not difficult to find fabrication, exaggeration, or half-truths (conscious or not) in Diego’s references to Inés Acosta, the paternal grandmother whose memory assumed unexpected importance in the intellectual, cultural, and even political circles where the artist moved.

Once, in an interview with photographer Marcel Sternberger, Diego assured that Inés came directly from the lineage of Uriel Acosta, a Jewish philosopher who was born in Porto around 1580, and one of the main references of the rationalist Baruch Espinoza: “I think I might have something to do [with Uriel],” he tossed in the air, before the unconvinced look of the interviewer, as one can read in Sternberger’s biographical portal.

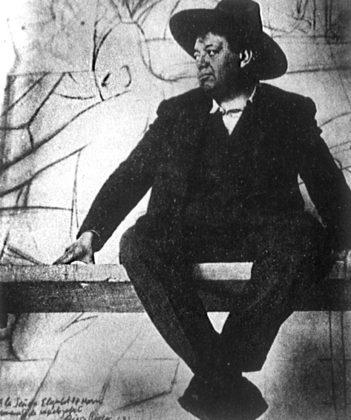

Diego Rivera is the most valued Latin American painter in the art market worldwide.

Diego Rivera is the most valued Latin American painter in the art market worldwide.

About these kinds of episodes, one of the muralist’s biographers, Patrick Marham, states in “Dreaming with Eyes Open” that Diego “was very pleased with his exotic ancestry,” not only Portuguese and Jewish but also from other European countries. “This gave him access to a distant memory of wealth, a connection to the aristocratic Europe of the Conquest, and a portion of military daring, intellectual distinction, and Jewish distinctiveness.”

This “ancestry” may have also influenced the political life of Diego, an important figure in the Communist Party of Mexico and a staunch Trotskyist. In an unsigned article on the Marcel Sterneberger Collection portal, it is inferred that both Diego and Frida claimed Jewish heritage to “gain status and sympathy” in the Communist movement, marked by Jewish personages such as Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky.

Diego himself would give the answer to these considerations, in 1935: “My Jewish side is the dominant element of my life, from here arose my sympathy with the oppressed masses, which motivates all my work.”

Memories of a Sunday afternoon at Alameda Central

Alicia Gojman does not believe that Diego used his roots for political or cultural credit. “He felt Jewish and was very concerned about the community, especially from the moment Hitler took power and fascist and Nazi groups began to emerge in Mexico,” the UNAM researcher tells NM. “In this effort to denounce”, she adds, “Diego even published an article in a US magazine in which he revealed where the Nazis were in Mexico, where they had radio stations, and where they received propaganda material.

The painter’s relationship with his Jewish and Portuguese antecedents was also reflected on an artistic level. In “Memories of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Central,” one of the muralist’s masterpieces, Diego depicts the tragedy and torture of Mariana de Carvajal, one of the symbols of the terror of the Inquisition in Mexico.

Mariana was Portuguese and belonged to a family of New Christians from Trás-os-Montes who arrived in Mexico in 1583. They were accompanying Luis de Carvajal, who had been sent by Spain to found the New Kingdom of Leon (now the Mexican state of Nuevo Leon, in the north of the country). The inquisitors always controlled their steps. In 1590, the entire family was sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of secretly practicing the Jewish faith. Five years later, the charges were reinforced and the sentence to the stake was carried out immediately.

The young Mariana de Carvajal was considered “mad” and was only convicted in 1601. In “Jewish Blood in New Spain”, a text published in the catalog of the exhibition “Diego Rivera and the Inquisition”, Ana Carpizo relates: “The torment consisted in leading her through the streets of the capital of New Spain - mounted on a crossbow, proclaiming her crime - until she reached the market of San Hipólito, where she was strangled with a garrote until her neck was broken before her body was burned”.

Mariana was murdered at age 29 on the grounds now occupied by Mexico City’s Alameda Central.

The schism between Diego and Picasso

It was in Madrid and Paris that Diego began to forge his style, as he studied works by European masters and conversed with artists such as Picasso and Modigliani.

The Mexican painter first arrived in Europe in 1906, after winning a scholarship. In 1914 he became known among the cubists in Paris. That same year he met Pablo Picasso, already a big name.

Marevna, a Russian painter who emigrated to Paris, wrote in her memoirs: “Picasso… used to go to Rivera’s studio to (…) shamelessly examine all the paintings. More than once Rivera complained: ‘I am fed up with Pablo. If he plagiarizes me (…) I’ll run him out of my house”. Said and done in 1915 the varnish broke. Enraged by seeing Picasso’s painting “Man Leaning on a Table,” Diego accused the Spaniard of plagiarizing his work “The Zapatista Landscape” and promised to “break his head,” says Marevna. Which never happened.

After 15 years in Europe, Diego Rivera finally returned to his country in 1921, with the firm idea of dedicating himself to muralism.

“The Elephant and the Dove”

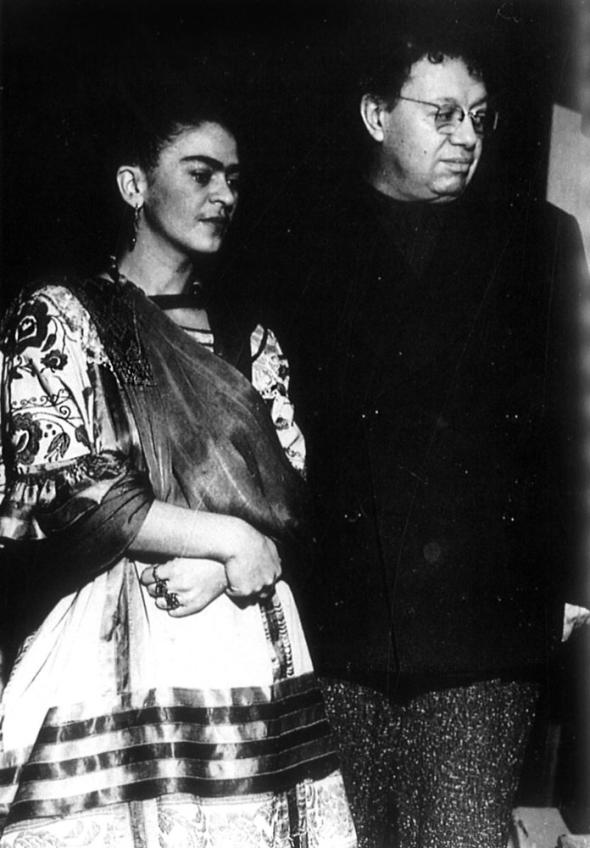

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo are one of those movie love stories. In 2002, Julie Taymor’s film Frida turned this couple into a universal romantic myth.

The two artists were first married on August 21, 1929, “They said it was a marriage between an elephant and a dove,” the painter recalled. The marriage, passionate to the marrow, was marked by Diego’s infidelities. In 1939, they finally divorced… only to remarry a year later, on December 8, 1940, in a relationship full of lovers consented by both.

About Diego’s relationships, Frida wrote: “I know that all these letters, adventures with women, ‘English’ teachers, gypsy models, assistants with ‘good intentions,’ ‘plenipotentiary emissaries from faraway places,’ are only coquettishness.”

From 1940 on, the painter began to shine a light of her own in the artistic milieu. But her health condition was precarious. One summer night, she warns Diego, “I feel that I will leave you very soon.” A day later, in the early morning hours of July 13, 1954, Frida succumbs. “It was the most tragic day of my life,” confessed the muralist.

Diego Rivera left three years later. But first he asked to be incinerated, and that his ashes be mixed with Frida’s, “molecule by molecule,” he wrote in a letter to Toño Pelaéz. The reunion never took place. Diego was buried in the Rotunda of Illustrious Men in Mexico City. Far away from the emblematic Blue House where Frida rests in peace.

The relationship between Diego and Frida built a passionate love story that marked the works of both artists.

The relationship between Diego and Frida built a passionate love story that marked the works of both artists.

*Published originally in “News Magazine”, 12/9/2018