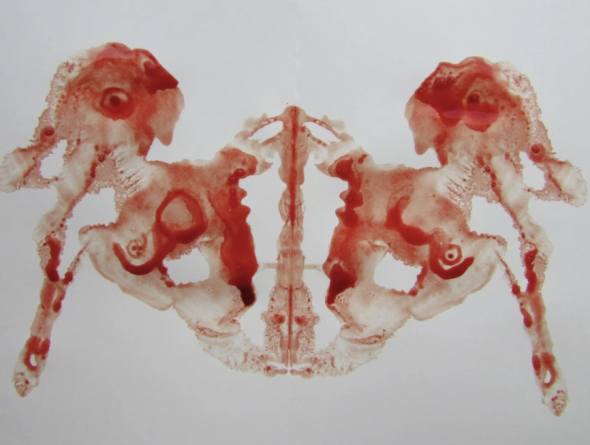

Clots from the woman who didn't want to be

This text is autobiographical. You probably don’t want to hear about a stranger’s life, I’m not anyone too important to warrant a biography. But this text is biographical, period, and although it is, if you’re a woman you might even think it’s about you. It could be a chronicle, perhaps, if you think it would be nice to say so. I could call it a chronicle, and that would avoid unnecessary excuses and justifications. I’m a woman. An adult woman who has a body, a body that serves me and that I often serve, and this is the reason for this text-chronicle, or humiliating rant for someone who has a body with ambitions. Yet here I am with my body, and while it doesn’t mock me and rub my incompetence in managing it in my face, it deceives me as I use it to generate some interaction with the world of the living.

To better understand this story, we need to travel back to 1996. I was fourteen years old and I was wearing a bikini, because at that point in my life I was spending months in a row in a bikini when everything around me was one big, huge, endless summer, a summer whose marks I still bear on my skin today. I played in the sand like a child until hunger made me go for lunch. I grabbed some clothes and anything I could get my hands on, maybe a toy, a bucket, I don’t remember. But I remember that I ran to the bathroom to pee and bled, bled and felt the blood flowing down, and I looked and cried. I cried at the sight of the blood because I knew something changed, but I didn’t want it to change. Of all the girls my age, I was the last to menarche. I was fourteen, with two lumps for tits, a gaunt and weak body, bones showing, thirty-something kilos just on my knees, a girl who didn’t want to grow up.

The day I turned ten, a friend menstruated, after which they all got their periods, one by one, while I celebrated my prolonged girlhood. I followed this for four years, as happy as I was terrified, and I think my fear was what kept putting off my time. At the time I didn’t really understand, I wasn’t conscious, I was just a feeling body, but I look back and I understand why. Children have no gender, not in general. And if they do, it’s not very important. A child is all childlike and gender limits are easier to deal with. Even so, with all these demands, raised on the beach, loose in the slums, it was easy to feel the demarcation of territories. The territories that, being a child, I dared to pass, but by being a woman it would no longer be admissible. My mother heard me crying, went into the bathroom, saw the blood and glared. And all I could say was that my life was over. Just like that, with that touch of drama so peculiar to myself: ‘my life is over.’ And naturally my mother, meticulously trained to be a woman, said I was being dramatic, because I was, it was true. And words have power, indeed they do. I’ve never been the same since that day. I’ve spent my whole life struggling with these boundaries, not understanding which of these stakes had been imposed on me and which were in fact the boundaries of a genuine womanhood. I put up with that menarche, washed my dirty bikini as my mother had taught me, and for all the months that followed I was argued with about the real and imaginary territory of this good and bad schizophrenia called a woman’s body.

Women can’t. She can’t dance, spread her legs, speak loudly, she can’t be, she can’t win, she can’t have, she can’t get dirty, she can’t decide. Women can’t cross that line, they can’t jump that rope, they can’t live that life. That blood on my bikini came to tell me what my ear didn’t want to hear: that I couldn’t. It didn’t make sense, because I felt I could do anything, and so with my skinny arms I pushed forward and pushed the ropes, knocked down the bricks, kicked all the fences I saw in front of me in a daily attempt not to accept seeing my life end. I didn’t accept the message of the blood that I myself have spilled and will spill until I become old. I don’t know if it’s fate or karma, I don’t know if it’s the material structure of the world, but being a woman isn’t easy for any of us and it wasn’t for me. Misfortune led me to the illusion that the less of a woman I was, the more I could cope with living in a world that wasn’t designed for us.

Cut last week

I tripped over a pair of scissors while walking down the street and now I’m bald.

A lie.

Carla Diacov, in A Menstruação de Valter Hugo Mãe.

Carla Diacov, in A Menstruação de Valter Hugo Mãe.

Much bigger issues have kept me indoors for three whole cycles without a breath of fresh air, and if you’re a woman, you might understand. Crying spells, panic attacks, sweating. The moon discovered my dry eyes at the window and just when I thought I could hide again, and again, and again, it found me and poured all the energy capsules of a lifetime’s backlog into me. A lifetime of bleeding and crying. A lifetime of undoing the body to understand the body, to receive the body. This is configured in many ways. A woman disconnected from her womanhood loses her hair, loses her scales, becomes a porpoise. And a porpoise is a man, even if it’s a fish, and even if it’s female. A thing, ladies and gentlemen, is a thing. The other is a porpoise, and a porpoise is a porpoise, a woman is a woman, one is slippery and the other isn’t. And there comes a time when you’ve pretended so much that you’re a porpoise that you believe you’re a porpoise, you talk like a porpoise, you sing like a porpoise, you love a porpoise the way porpoises are loved. But the blood comes and reminds you that you’re a woman. A witch once told me: “Women with blood problems need to connect with the feminine.” And I thought: “but I even wear lipstick.” Dumb thing. The feminine is a woman’s body. This body is capable of anything that no other is capable of. A woman is not a porpoise, a woman carries with her the pouch responsible for populating the whole earth, nourishing it with her blood. The blood fertilizes leaf by leaf, root by root, critter by critter, everything that is to be life. This body is capable of anything that no other is capable of. A woman is not a porpoise, a woman carries with her the pouch responsible for populating the whole earth, nourishing it with her blood. The blood fertilizes leaf by leaf, root by root, critter by critter, everything that is to be life. This body is capable of anything that no other is capable of. A woman is not a porpoise, a woman carries with her the pouch responsible for populating the whole earth, nourishing it with her blood. The blood fertilizes leaf by leaf, root by root, critter by critter, everything that is to be life.

And then, three whole cycles passed without needing to be a porpoise, or a man, or anything other than just me and my body, a trance. Honestly, if you’re yours, you know what it’s all about. The sweat that comes from your scalp and breasts reminds your body that you’re a woman. When I blinked, there wasn’t a hair on my head. It wasn’t as planned, I can’t tell you what I did because I don’t even have the same memories. I have flashes of machine noises somewhere around me. With the hair on the floor, I hear the copious sobbing of someone who lets go, but also of someone who lets in. A woman is not hair, a woman is not hair. I looked in the mirror and saw someone else. A person with no hair who was crying to be welcomed and to leave.

It was seven days of blood and, oddly enough, blood that I let drain without stopping. When my legs were dirty, that’s when I saw them clean. The power of a life that ironically began the day I stopped fighting. Seeing my hair go hurt. It hurt just as it did in 1996, when they told the girl to leave, against my will. I hold the girl in my teeth like some others hold on to spring. And in that life, all my blood wept for the wounded girl. I left my hair on the floor and decided to become a woman after all. Together with the blood that pours out, they’re the fiber and salt that will fertilize the soil of this world that is called earth, but should be called a womb.

Carla Diacov, in A Menstruação de Valter Hugo Mãe.

Carla Diacov, in A Menstruação de Valter Hugo Mãe.