The Awakening of African Cinema [1962]

From June 27 to 29, 2013, the University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL) will hold the 5th European Conference on African Studies (ECAS 2013). In parallel to the academic panels, there will be a film festival, the ECAScreenings, and a roundtable, The State of the Art: African Contemporary Cinema in Focus. BUALA is a partner of ECAScreenings in the publication of articles focused on cinema related to Africa. The articles are selected by Pedro Osório Graça.

…………..

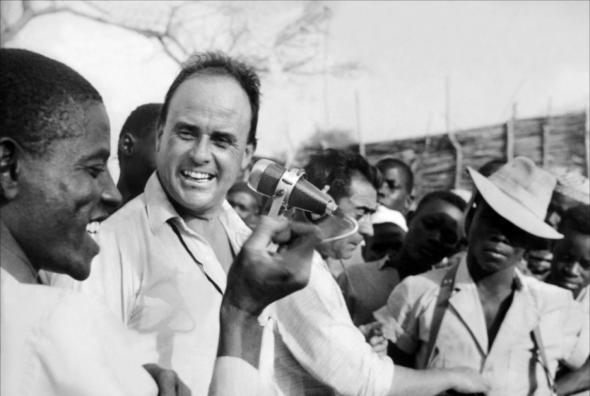

Today a new African cinema is coming into being, which is adding something new and significant to the cultural and artistic life of this continent. The importance of this development was underlined at an international round-table discussion held last year in Venice on “Africa and Contemporary Civilization”. At this gathering Unesco presented several studies on the cinema in Africa. The article below is an edited and abridged version of a study by Jean Rouch, in which the French film producer traces the development of the cinema in Africa and looks at some of its new trends. The subject will also be dealt in future issues.

Jean Rocuh

Jean Rocuh

The cinema made its debut in Africa in the very first years after its invention. A vaudeville magician managed to steal one of the first “theatregraph” projectors from the Alhambra Palace theatre in London in 1896 and used it to introduce motion pictures into South Africa. It is interesting to note that South Africa still employs the turn-of-the-century word “Bioscope” to describe a cinema theatre.

In West Africa the first motion picture projections go back to 1905 when mobile cinemas began showing animated cartoons in Dakar and in surrounding villages. It was also during this period that explorers first began to use motion picture cameras in the course of their travels. The French Film Library (Cinémathèque Française) in Paris possesses several catalogues by Georges Meliès which make mention of the first films made in Africa.

Since this early pioneering period the cinema has witnessed quite an extensive development in Africa. Tropical Africa, however, has remained one of the most under-developed regions as far as film showings are concerned, and the world’s most retarded continent in the field of film production.

While Asia and South America have been making films for years (in fact Japan, India and Hong Kong are now the world’s three leading producers, ahead of the U.S.A. which has dropped to fourth place), tropical Africa has as yet to turn out its first full-length feature picture. As the French film historian Georges Sadoul recently wrote: “Sixty-five years after the invention of the cinema, not one truly African feature-length film has been produced to my knowledge. By the fact I mean a film acted, photographed, written, conceived and edited by Africans and filmed in an African language.”

Now, at a time when a true African cinema is about to be born, I think it is worthwhile to take stock of what has been done, what is now being done in Africa and to examine the new trends of African cinema.

The first films shot in Africa were frankly “exotic.” They showed the strangeness of the continent, viewed as a land of “savages” and “cannibals”. The African was portrayed as a wild creature whose behavior was intended to provoke laughter when it did not border on the pathological. With the end of the first World War came the stereotype of the childish, good-natured native.

The first noteworthy film about tropical Africa was probably Croisière Noire (Negro Cruise), made by Frenchman Léon Poirier during the first motor-car trip across Africa from north to south in 1924-25.

The basic theme of the film was the epic automobile adventure, but parallel with that it showed the most representative aspects of the people encountered en route. Through the team was pressed by time the film men proved their ability both in choosing and seeing their subjects. The scenes they shot are now dated but nevertheless remain priceless documents on Africa and the history of its cultures.

There can be no doubt about the sincerity and good intentions of the authors of this film. And yet two facts stand out sharply today. The unit simply did not understand the world they were filming and which they glimpsed only scantily. Second, even when they had more time on their hands during long halts, their approach was that of the “let-us-look-at-the savages” type with scenes of platter-lipped women, details of certain circumcision rites, or aspects in the life of pygmies.

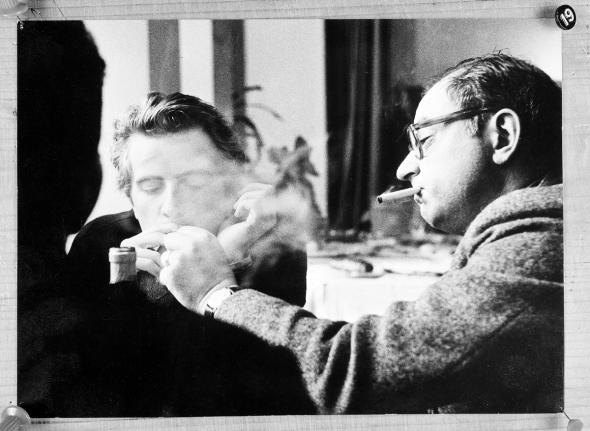

Jean Rouch with Edgar Morin

Jean Rouch with Edgar Morin

Although photographed with a maximum of objectivity the scenes remained cold, if not ironical. They had none of the human warmth which we find in the earlier or contemporary films made by Robert Flaherty such as Nanook of the Earth or Moana.

The same can be said of most of the exotic films of the time when Western cameras were discovering the rest of the world with Marco Polo-type lenses, or just about. The situation worsened in later years when we find the camera portraying Africa as a continent of barbarism and cruelty, although it must foe admitted that Africa was not the only region to undergo such treatment. Asia, South America, Greenland were brought to screen with paltry sequences of savage dances, guitar strummers and primitive hunters.

But this period also gave us Trader Horn which created a sensation by showing an African devoured alive by a crocodile (it was never learned whether the scene was faked or an accident) and especially Sanders of the River starring Paul Robeson. Sanders of the River was one of the first good talking pictures to be made on Africa and was quite a success in tropical Africa.

The late 1920s also saw the appearance of the first true documentary films about Africa. André Gide had gone to the Congo in 1926 and had taken with him Marc Allegret who returned to France with Voyage au Congo (1928). In 1938 the African specialist Marcel Griaule produced two anthropological films in the heart of the continent, using soundtrack with 35 millimetres. Au Pays Dogon (In the Land of the Dogons) showed the daily life and religion of the Dogons. More important was Sous les masques noirs (Under the Negro Masks) a film relating the funeral rites and costumes of a Bandiagara cliff village in what is today the Republic of Sudan.

Two years before, Jean d’Esme filmed La Grande Caravane in eastern Nigeria which told the story of a caravan journey to obtain salt. The same year G.H. Blanchon produced a short film in Guinea, Coulibaly à l’Aventure. Though completely ignored, it deals with one of the most important problems of West Africa – the migration of young people from the savannahs to the cities on the coast. This could have been one of the most valuable documentaries to come out of Africa if the film had not been ruined by an exasperating commentary.

It is only after the second World War that we find a valid African cinema developing both in documentaries and in feature films.1

The last war indirectly helped the development of African cinema, for during this period army field services had to use portable film equipment, thus permitting 16-millimetre film, previously reserved for amateurs, to prove its worth.

The 16-millimetre movement was born immediately after the war and took hold particularly in France. French youth, emerging from the Occupation, from the armed forces or the Resistance, was seized with an irresistible wanderlust. The Musée de l’Homme, the anthropological museum of Paris, became a magnet for young Frenchmen eager to discover the world for themselves and thirsting for adventure.

Thanks to these young men probably the first real archives of recorded African music were assembled on tape and film. It was this more than anything else which made it possible to add authentic musical sound tracks to African films without resorting to outlandish and wholly inappropriate exotic music.

Certain black-and-white 35 millimetre films made at this time, such as Danses Congolaises, Au Pays des Pigmées and Pirogues sur l’Ogooué, have remained the first top-quality images and sound recordings made in tropical Africa. These films are documentaries but they constitute exceptional records of the traditional dances of the Confgo, the daily life of the Babinga pygmies, and canoe transportation on the Ogowé River in Gabon.

The year 1950 marks a turning point in the growth of African cinema. The films produced in the preceeding years had shown that the era of the cheap exotic film of prewar years was ended, and showed that there was a great need to learn more about Africa if the cinema were really to be used as a medium for telling spectators of other cultures about it. From 1950 until today African cinema has revealed five main tendencies.

1. EXOTIC AFRICA: apart from the Tarzan films, in which Africa is only a mere pretext for the locale, a number of producers continue to work with the vein of the “cannibal” and the “dance of the witch doctors.” Here, as in prewar days, Africa is only a stage setting and the Africans themselves miserable extras.

2. ETHNOGRAPHIC AFRICA: here we find film-makers and anthropologists attempting - clumsily at times - to portray the most authentic aspects of African cultures. The influence of the ethnographic film has gone beyond the domain of scientific research, and has already greatly modified the approach of a large number of commercial films made in Africa.

In the field of the pure anthropological film the work of the Belgian Luc de Heusch deserves special mention. As anthropologist turned film-maker, de Heusch has attempted to use the motion picture as a supplementary tool in his scientific research. Though unpretentious, his films (such as Fêtes chez les Hamba, 1955) are conceived and executed with great care, and still remain as existing and authentic records of the cultures of the Congo prior to the disorders of the Independence period.

By contrast, Henry Brandt of Switzerland is a film-maker who turned to anthropology to make a film in Africa. In the 1950s Jean Gabus, director of the Ethnographic Museum at Neuchatel, Switzerland, led an anthropological mission to the Niger to study a nomad savannah people, the Bororo Peuhl herdsmen.

He later sent Brandt to the area where he spent half a year alone with the herdsmen. Brandt, using 16-millmetre, returned with a colour film of extraordinary beauty and a sound track with musical recordings of remarkable quality and authenticity. Jean Gabus had told him that his purpose was not to amass “museum documents” but to foster understanding and respect of other men (“faire comprendre et respecter d’autres homes.”)

His film, entitled Les Nomades du Soleil (Nomads in the Sun) and completed in 1956, is now considered a classic, although it has never been shown commercially. (Commercial distribution is now being arranged and the film will soon be show in European cinemas — Editor.)

At first these experiments were not very well received in scientific circles. When an ethnographic film committee was set up at the Musée de l’Homme to teach anthropology students cinema techniques certain ethnographers raised the cry that more attention was being paid to “picture chasing” than to scientific research.

Despite much protests an important school of ethnographer-film makers specializing in African has now grown up and as a result the making of ethnographic films is being taken very seriously by the professional world itself.

In 1951, the professional film maker Jacques Dupont turned out a really magnificent documentary, La Grande Case(The Long House) which he shot in Western Cameroon, and Pierre-Dominique Gaisseau, another professional, went off to Guinea to make a group of films, including Fôret Sacrée (Sacred Forest), Naloutai and Pays Bassari (Bassari Country).

3. CHANGING AFRICA: films which attempt to show traditional Africa in contact with modern world ant the problems this raises (anthropologists called this “acculturation.”)

Here the cinema faces the same problems as does African sociology, principally that of ignorance of the traditional cultures which are now undergoing rapid change. This is no small handicap and it is evident in many films (mostly of the pro-national documentary type) where we find the old dying cultures disdained and ridiculed and little effort being made to understand them.

The first film on acculturation in African was the French documentary, Coulibaly à l’Aventure, made in 1936, and already referred to. Fourteen years were to pass before this subject was to be brought to screen again. In 1950, a young student at the Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies (IDHEC) in Paris, named René Vautier, produced a clandestine film in the Ivory Coast on the struggles of a new political party then under attack by the colonial administration. Shot in 16-millimetre black-and-white with a makeshift sound track, the film, called Afrique 60, was banned in Africa and France and has been shown only on a film library circuits.

Another banned film was Les Statues Meurent Aussi (Statues Also Die) made by Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. It was made up of sequences filmed in European museums dealing with Africa and supplemented by footage from film archives on which they did an extraordinary job of editing.

The theme was that the statues of Negro art in our museums are denatured because of their true meaning is lost to us, and that the new African influenced by the West is completely decadent. (An edited version of this violent film is scheduled to be released shortly – Editor.)

This was the period when African students at IDHEC began to make their first films in Europe (they were unable to operate in their own countries). A group consisting of Paulin Vieyra, Jacques Melokano, Mamadou Sarra and Jarlstan (the cameraman) produced what is probably the first film ever made by Africans. Called Afrique sur Seine (Africa on the Seine) it portrayed the life of African Negroes in Paris. Unfortunately the editing and sound track were never finished.

Since 1950 films dealing with the theme of changing Africa have been produced in practically every country of tropical Africa. But in most of them (such as Paysan Noir – Black Peasant, L’Homme du Niger – Man of Niger, or even Sanders of the River) Africa’s traditions are viewed as archaic and unworthy of surviving alongside Western culture which is almost as synonymous of progress.

But three films, I feel, merit special praise. One of them Men of Africa, was shot in East Africa, and describes the rivalry between educated Africans and more primitive forest pygmies; Carlos Vilaredobo’s C’était le premier chant (The First Song) in which a young French official tries to better the lot of a bush village community reduced to poverty by drought and lack of initiative; and The Boy of Kumasenu filmed by Sean Graham and the Ghana Film Unit in 1952. It is the story of a boy fisherman who abandons his lagoon village for the big city only to come face to face with crime and corruption and narrowly escapes becoming a delinquent himself.

Two films made by Claude Vermorel in Gabon and Guinea belong in a class apart. In Les Conquérants Solitaires(Solitary Conquerors) and La plus belles des Vies (Best Way of Life), Vermorel takes the opposite view on cultural change showing a European so taken by African cultures after getting to know them that he adapts their ways.

The political struggles for independence also inspired a number of films but very few, I feel, can be considered worthwhile.

4. THE TRUE AFRICAN CINEMA IN EMBRYO: The films mentioned thus far were all attempts by foreigners to bring their own impressions and interpretations of Africa to the screen. But soon certain film producers began to feel that this was not enough, that a further step had to be taken to banish the exotic completely and to bring cinema audiences into direct contact with the people of Africa be they traditional or modern. This was to mark the first stage of the true cinema of Africa yet to come. And here the modest ethnographic film was to play an influential role.

The first film of this kind came to us from South Africa, where as early as 1948 a South African pastor, the Reverend Michael Scott, produced a 16-millimetre film, Civilization on Trial, which showed the reaction of the Negro himself to racial segregation. A minor masterpiece was later achieved by Donald Swanson, of Great Britain, with his Magic Gardenwhich recounts the unbelievable adventures of a Johannesburg thief. In similar vein is Sean Graham’s Highlife (renamed Jaguar) which he filmed in Ghana.

A much graver message - that of the very victims of racialism - was soon to come from South Africa when Lionel Ragosin, of the United States, filmed Come Back Africa in 1959. It is perhaps justifiable to ask whether this film is not Ragosin’s own cry of despair against Apartheid rather than that of South Africa’s Negroes. But whatever the direct0r’s role may have been the fact is that in his film it is the voice of Africa which speaks and he is no longer master of what he has unleashed.

For several years I have attempted to work in the same spirit. When I filmed Les Fils de L’Eau (Sons of the Water), a traditional ethnographic picture, I did my best to avoid the trap of exoticism. Flaherty had shown me one way of setting up a documentary. As a director he arranged and built up a series of scenes from real life, divorcing them from their alien background thus rendering them accessible to audience the world over. But no one can hope to equal Flaherty’s success in making the Eskimo Nanook, a real friend of people who had never even seen an Eskimo.

I therefore decided to try another way by letting African speak for themselves and putting them on film their spontaneous comments on their life, their work and their opinions. In 1954-55 I tried this method with Jaguar, letting three young Nigerian emigrants tell their story of a more-or-less imaginary journey to Ghana. (This film is still unedited.)

In 1957, I carried out the same experiment in the Ivory Coast with Moi, un Noir (I am a Negro.) I showed a poor Abidjan stevedore, a silent film I had made on his daily life and asked him to improvise a commentary on it. The result was amazing. The stevedore, Robinson, was so stimulated at seeing himself on the screen that he improvised an extraordinary monologue in which he not only reconstructed the conversations filmed out but commented on them and even criticized himself and his friends.

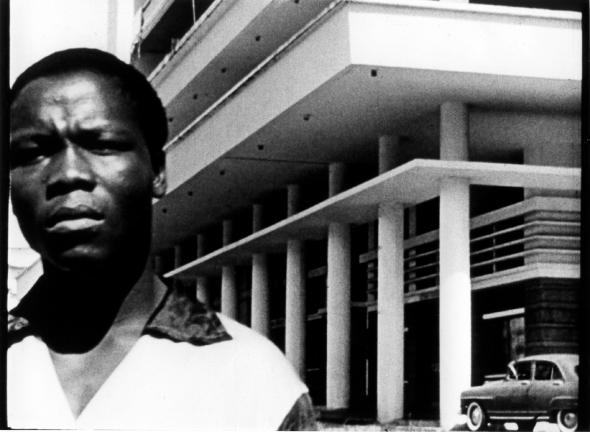

Moi un noir, Jean Rouch, 1959

Moi un noir, Jean Rouch, 1959

5. AFRICAN CINEMA BY AND FOR AFRICANS: I think we have now gone as far as we can working along these lines. No matter what we attempt neither Ragosin nor Graham nor myself will ever be Africans, and our films will always be films on Africa made by foreigners. I am not implying that there is anything really wrong with this, and it will certainly not stop us from continuing to make African films.

But it is time for a Changing of the Guard. In fact it has already started with the technical training of African film-producers. Paulin Vieyra, the first African to study at the Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies, has been teaching in Dakar for the past several years. He has made a film, slightly clumsy though it may be, called Un homme, un idéal, une vie (A man, his ideal and life) about the frustrations of a fisherman from the coast of Senegal who defied tradition by installing a motor in his canoe.

The film does not pass judgment on African traditions, it simply states them, depicts them. And when in one scene the trees of the forest speak of the village elders, there is not even a hint of mockery.

Lack of funds have prevented the film from being completed, but Vieyra has other plans; he is no longer alone. To mention only French-speaking Africa, it is to him and his colleagues, Blaise Senghor, Timité Lassari, Thomas Coulibaly, Jean-Paul N’Gasza and others that we must look for the films we all so eagerly await.

Originally published at The Unesco Courier, March 1962.

ROUCH, Jean, 1962, “The Awakening of African Cinema” [Online], The Unesco Courier, No.3, 10-15. Avaiable:http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0007/000782/078286eo.pdf [viewed 27 June 2013].

- 1. Note should be taken of a religious film, Soeurs Noires (Negro Nuns), shown in Paris in 1935 and in which the actors spoke Zulu. In the 1930s German film-makers made a number of films on Africa as part of the world-wide documentary series of EFA and Tobis films. From these perhaps came some of the sequences for Melodies of the World, by Walter Ruttman in Germany.