To be African in Cape Verde is a Taboo

Cape Verde is not Africa, Cape Verdeans are “special blacks” and the closest to Portugal. Cape Verde is the country of miscegenation, the “proof” of “racial harmony” of Luso-Tropicalism. For many years, this was the dominant narrative. To be or not to be African continues to be a question.

Jorge Andrade only speaks creole. He can speak Portuguese but uses the Cape Verdean language as the communication tool to affirm his Africanity and mark the distance from the colonial past. “Creole is a weapon of intervention”, he explains in the studio of Rádio de Cabo Verde, where he runs the only radio programme that talks about African questions. “Our capacity to understand, communicate, think, dream is all in creole. People feel free talking in creole and feel oppressed speaking the language of the colonizers.”

Explaining himself, Jorge Andrade is not against Portugal, nor against the Portuguese or their language, but rather the European cultural imperialism “towards Africa and Africans”. He has no problem at all speaking Portuguese. However, whenever possible, he makes the Portuguese try to listen to and speak in creole.

Jorge is a charismatic figure, and this is clear in the way he arrives at the Ponta d’Água neighbourhood in June this year, sitting in the middle of the street in front of a group of young people and speaking about racial questions like a preacher, full of conviction and faith. He is not in the habit of mincing his words to express his thoughts. He has long dreadlocks, held in place with some type of white cap, falling over his white shirt and dark tie.

Probably because we know that he lived for several years in the United States, when we see him chatting with the neighbourhood’s youngsters, figures like Martin Luther King come to mind. He uses English words to explain his thoughts more easily than with Portuguese vocabulary. The group of around ten young people look at him and listen attentively. Night falls, but they do not leave or lose interest. On the contrary, the conversation heats up as more people stop by and join in. “What is interesting is that Africans outside the continent know more about Africa than us here”, he comments. “Our knowledge of Africa is almost null”, he addresses the young audience regretfully. “The presence of Africa in the Bible, for example, how is it?”

Jorge Andrade goes on to discuss the role of religion and of new churches, which will be even more packed if we are not able to pass the African culture on to the youth, for sure. “If Africa is a religion, I am a minister”, he comments. “But each minister has his own conscience.”

The daily mission of Jorge Andrade, who goes from one neighbourhood to the other discretely, is to spread the message of Africanity among young people bombarded with miserly images of a continent where History existed before the arrival of the Europeans.

A woman joins the group, Keyla. She comes to learn about Africa and Pan-Africanism, something that is not taught in school. One of the young people, Tosh, 35 years old, finds it interesting that the education system and the official narrative, early on, have transmitted the idea that Cape Verdeans are different from their “brothers of the western coast”. Sent to occupy administrative positions in other colonies by the Portuguese, “until today, Cape Verdeans think that they are not Africans, that they are more intelligent and are wiser than their brothers on the continent”. This “starts with colonization. The idea was instilled in our minds and is alive in our society today. We face a serious identity problem. Even when History tells a different story, Cape Verdeans refuse to believe, for it is in our DNA since colonization. This is our society, a real confusion”.

Several definitions over the years have characterised Cape Verde as a country that is not in Africa nor in Europe. Many Cape Verdeans themselves incorporated the concept, so much as that this ambiguity is part of the description of Cape Verdean identity in some cases. Related is the question of miscegenation, which Jorge Andrade defines as “a violence”: “The moment we think of miscegenation, we think automatically of sexual violence” committed by a European man against an African woman. “We find a constant remembrance of the impact of colonialism and slavery in the colour of our skin”, he asserts.

Among other things, Jorge Andrade promotes the teaching of the history of Cape Verde before European arrival in Africa: “Africa had millennia of great and robust civilization”, he begins. “It is a major failure that Cape Verde traces its identity to the arrival of the Europeans. How can a people conceive its history based on an act of degeneration? No Cape Verdean is free while their history begins with slavery, they face an identity crisis and the question: who am I?” A brief example: “There was the empire of Mali, centuries before Portuguese arrival; Africa had its renaissance before, with Egypt.”

Adriano Miranda

Adriano Miranda

Jorge Andrade is sure that Cape Verdeans maintain a distance from Africa for racial reasons. “As long as there is white supremacy, everything is mixed up.”

He defines himself as an Afro-Cape Verdean, knowing that the archipelago had people from Senegal, Gambia, Mali, Guinea-Bissau – the mixture is not only Cape Verde and Europe. He thinks that it is important to transmit the histories of History to young Cape Verdeans to restore a silenced version and to boost their self-esteem and enable them to raise their heads.

“We are Africans, obviously. But, in practice, where are the policies since 1975 that defend African interests? None. What model of education does the Ministry of Education promote?” From health to law, all the references are Portuguese. The solutions, though, are not, and cannot be Portuguese because African problems are different from European ones.

The ambiguity is so great that a Cape Verdean enters a travel agency in Praia, the Capital, on the island of Santiago, and only sees tour packages to Europe – not even one to Africa. “Do you know that there were no maps of Africa in any of the bookstores in Cape Verde? How is it possible that there is not even one map of Africa in a country that is considered a model of democracy?”

The European projection on Africans, and the economic, social, political and cultural clout of Europe that influences and determines the capacity for development or underdevelopment based on race is what he means by racism. “Malcolm X said: ‘Who taught you to hate the colour of your skin? Who taught you to hate the shape of your nose, the shape of your lips, the texture of your hair? It was the same man that want to continue to dominate you.”

The Cape Verdean ambiguity was produced and fed by the Portuguese – up to this date. In 1822, all the inhabitants of the Portuguese colonial empire were considered citizens; the indigenous status was applied up to the 1960s in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau – most of the native population were indigenous, except for the assimilated, that had to comply with certain requirements like eating at the table with fork and knife and speaking Portuguese. However, Cape Verde was conceded a special status for having “more miscegenation and similarities with Portugal”, and in 1947 the Cape Verdeans would be considered citizens. They were also sent to Guinea-Bissau to integrate the colonial administration. On the other hand, they assumed the opposite role in the farmsteads of São Tomé and Príncipe, to where they went and were used as forced labour almost until independence. This is, nonetheless, a rather silenced narrative in Cape Verdean history.

As António Tomás writes in a biography about Amílcar Cabral, The Maker of Utopias, “the various Portuguese administrations never know clearly what to do with Cape Verde”. “While Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique were unequivocally indigenous colonies, Cape Verde was a case apart. The locals were civilized and the archipelago, legally, was half way between a colony and an adjacent region, like Madeira and the Azores. And it was more for logistic and not political reasons that Cape Verde was never granted a status like that of the Portuguese islands in the Atlantic.

Africa tattooed on the arm

Edson Liver, 23 years old, has a map of Africa tattooed on an arm. He is studying Education Sciences and wants to introduce African subjects in the school curriculum. It is Saturday, but activity day at the University of Cape Verde, and Edson talks to us about his passion for Africanity accompanied by sounds of music coming from the courtyard. He was present at the meetings with Jorge Andrade. There are many instances of cross-over in their discourses. “It was through him that today I know our history. The only radio that has an Africanist program is RCV+. One and only!”

In fact, he got the tattoo after this awakening. “The texts that we studied at school were mainly European. We need to affirm our identity. We are Africans, geographically and politically, but we do not have the basis to recognize ourselves as such”, he explains his tattoo. He feels that his generation is indifferent about this aspect of Cape Verdean identity. The independence hero Amílcar Cabral and other national heroes are not discussed as they should be; the awareness of Africanity is the most difficult part, he admits.

24 years of age and a graduate in Social Sciences, Evandra Moreira is an intern at the Cape Verdean Institute for Gender Equality and Equity, working as a research assistant. She is also aware of the existing racial problems and, despite thinking that there is no racism in Cape Verde, the truth is that Cape Verdeans have visible discriminatory attitudes towards Africans of the continent. “The way we treat Europeans is different from the way we treat our African brothers”, she explains.

The appreciation of what is Western and the depreciation of what is African is noticeable in the way Cape Verdeans dress and arrange their hair – all Western references. “Even in the way we speak. We do not care about neighbouring languages, we are indifferent to traditional cuisine, we do not care about having close relations with African countries, but we want to embrace what is foreign and develop relations with the European Union, Brazil, the United States…”, he criticizes.

He is worried about the language used, for example, to praise women – “you are black but beautiful”. Although people commonly say that they are not racist, their action tells a different story, Evandra defends. For instance, she heard in the street: a tourist, only dark-skinned, then he is not a tourist; a tourist should be light-skinned with straight long hair…

photo by Diogo Bento

photo by Diogo Bento

Banished from will

Historian António Leão Correia e Silva (1963 –), current minister of Higher Education, Science and Innovation, has a more optimistic vision for Cape Verde. “Of the few societies with a colonial past, a slavery past, Cape Verde managed to dismantle and disarm the racial question”, he begins. “No one has more or fewer social, professional and political mobility opportunities because of paler or darker skin”, he defends. A racial question per se does not exist in the Cape Verdean society, which does not mean that there are no traces of it. When a person is successful, he is said to have turned white, for example. “Whiteness is a metaphor for success.”

Nevertheless, he argues that the Luso-Tropical myth claiming that Portuguese colonisation is integrative and with it “the racial question is diluted” is not rigorously “based on sound historical survey”. “Racism is an official Portuguese ideology and it was state policy to combat miscegenation.”

Correia e Silva, one of the authors of General History of Cape Verde, also studied various wills of landed gentry, and observed in these documents “a clear hierarchy among the sons”. “The idea was to pass to the male, legitimate white son. In the case of heiresses, the question was more complicated – to defend a woman is to defend racial purity; a man can have sons [with the indigenous], but these stay in the quarters. It was interesting because, in many wills, wherein an heiress is involved, a clause was almost obligatory – in the event of marriage with a black man, she will be disinherited. The protection of the race was important because it would acquire a symbolic value.”

Society is contradictory, but we cannot say, because of this, “as some wish to conclude, there was no racist ideology: there was”. On the other hand, at some moments, miscegenation was a social promotion strategy. During the period of slavery, it was said that “a patient woman would seduce a white man and bear his child, because, in slavery, a mixed child was a means to liberation and, in rare cases, to legitimate the child”.

From the 17th century, Cape Verde was no longer an Atlantic centre for the commercial distribution of merchandise, nor was it capable of attracting new white people, he continues. Those already here had mixed children, “these gradually rose in power.” “So much so for the promotion of mulattos and of blacks, it was not the quarters replacing the big house, but the big house abating.”

For all that, Cape Verdean nationalism is not a consequence of the racial question, he believes. The revindication of independence was due to a cultural specificity of the archipelago, which had been appreciated in the imperial regime, he defends. The generation of writer Eugénio Tavares (1867-1930) believed in a unitary Portugal, not in a Portugal with separated colonies. That generation “would like access to public positions to be without discrimination based on place of birth or race”. Parity aimed at de-racialization – “there were also metropolitan allies who defended access to school.” The historian adds: “The 1822 revolution promised that, the 1910 Republic promised that, and there was great enthusiasm throughout Cape Verde. The elite were convinced about their capabilities. With access to education and the social belief that education capital was much more secure than investment in landed property, the revindication for access to school was politicized very early on.”

The Cape Verdean society is essentially creole but composite, concludes the minister. “Sometimes, from a continental African perspective, people think that Cape Verde is too Euro-Atlantic to be Africa; from a European perspective, Cape Verde is too Black-African to be Europe. Perhaps the archipelago is all this, perhaps it has various components, but it is an African frontier”, he argues.

Myth of miscegenation

There are, however, regional asymmetries. Today, an imagined identity is attributed to Santiago by consensus as the island on which the population shows more similarity with the African continent, while the inhabitants of the windward islands are considered more intellectual, educated and closer to Europe: the former group are called badios and the latter sampadjudos.

Adriano Miranda

Adriano Miranda

There is a historical explanation for this. For example, São Vicente, one of the five settled windward islands, also thought to be the closest to Europe culturally, was only inhabited in the 19th century, we are reminded by Iva Cabral, yet another historian.

In her home in Terra Branca, a neighbourhood in Praia, also rector of the Lusophone University of Cape Verde, she talks to us. “To say that Cape Verde is a mixed society skin deep is not true”, she comments. “It is a culturally mixed society, but not in terms of appearance. When Cape Verde was born, at the beginning of the 16th century, there were 200 white neighbours in Cidade Velha and five thousand blacks. However virile the Portuguese might be, it would be very difficult to miscegenate all of that: by the end of the 18th century, whites were 2%.” After independence, “a whole black population that was in hiding emerged from the bottom of the mountain” – the African story was always silenced.

photo by Diogo Bento

photo by Diogo Bento

Ival Cabral is daughter of one of the biggest icons of Lusophone Africa, Amílcar Cabral. She played an interventive role in the preservation of his memory. Little before we met, she protested the transfer of the Plateau market to the area of Várzia in front of the National Library, where the enormous statute constructed in 2000 in honour of the “founder of Cape Verdean nationalism” stands. She considered the change – in concert with many intellectuals that raised their voice – to be a disrespect for the memory “of Cabral”.

Compared with figures like the Portuguese seafarer, Diogo Gomes, who arrived at Santiago in the 15th century and had the right to a statute on one of the prominent sites of the city, close to Plateau, Amílcar Cabral is trivialized, according to some. The most eye-catching image of her dad, though, is found in the eponymous foundation in Praia. It is a mural in lively colours, where Cabral appears with his beret and eye-glasses. Downstairs there are photographs, works about his life and his own works. Carlos Reis, one of the administrators of the Amílcar Cabral Foundation, likewise agrees that the memory of Cabral is mistreated in the country. “There is no explanation, no development, and not sufficient knowledge about Amílcar Cabral.”

Born in 1953, Iva Cabral edited in 2015 the book The First Atlantic Colonial Elite, in which she analyses the formation of the elite of Santiago. She points out that it is difficult to talk about racial relations in Cape Verde today. “Historically, in Cape Verde, the colour of your skin depends on your social position. The first endogenous elite were called ‘brancos da terra’, literally ‘whites of the soil’. I would not say there was racism, but there was class, depending on the social situation of the individual. In Portugal, when I take the bus, I observe a white-black dichotomy, a person is judged by his or her skin.”

The truth is that “the Cape Verdean elite thought that they were white” and “superior to the rest of the population”. “Independence opens the gates of opportunity to African culture, to social mobility, when farmers have the chance to go to school – this was previously not possible because there were only two secondary schools, one in Praia, which opened in the 1960s, and another in Mindelo, which was inaugurated in 1917.”

At a certain point, Portugal wanted to make the Cape Verdean elite into an intermediary category between itself and the rest of the colonies – only the elite, because the rest of the population was badly treated, there were devastating famines in Cape Verde, she recalls – and this intermediation left scars, and not only on the archipelago, she analyses. “Portugal set aside the population of Santiago for being black and chose the elite of Mindelo for being similar.”

On the island of São Vicente, where there is a port, miscegenation was common and the European culture more present “because there was no slavery”, adds Iva Cabral. “When Mindelo becomes a city, slavery is coming to an end. The culture is different. When deciding to open a secondary school, Portugal chooses the island with the highest cultural similarity, where there are fewer slaves and rebellions. Santiago was a rebellious society. From the beginning there were slaves and rebellions.”

Cape Verde is a slavery society – an entrepôts for slavery from the 15th century – “that was born racist”, says Iva Cabral. And the unconscious of a slavery society “is very heavy”; “the problem of being African or not” is still present, exactly because “when we discuss Africa, we discuss slavery, we are never free from the burden of slavery in our subconscious mind”.

One of the consequences of that is ignorance about our family roots. African names were amputated, those who had mixed family had access to information about the Portuguese side only. “We, Cape Verdeans, do not know our past – a population with no generation. I know the past of my mother, from Trás-os-Montes, but I am in the dark about the past of my father’s family. The name counts. Here, the name was removed, religion, dances, folk tunes were prohibited – all this becomes our subconscious.”

Mirror for colour control

When I was in school, I had a “little round mirror” in the pocket, a “precious instrument” to control the tone of my skin and check if the sun was tanning it too much. Born on the island of Santo Antão, André Corsino Tolentino, 69 years old, retired in 2013 from a career in diplomacy, and ex-combatant of PAIGC, shares with us this episode in the living room of his home, where there are various African statutes hanging on the wall. “The tone of the skin was important, therefore, he peeped occasionally to check if it was paler or darker, because it was visible, and this criterion had social value and value for application to administrative service in other colonies. I remember that families were classified according to skin tone.”

photo by Enric Vives-Rubio

photo by Enric Vives-Rubio

Mulatto, Corsino Tolentino only acquired “real conscience” of the racial question when he was in Portugal, where he was treated as “black or not white”. “Here people deal with the situation by avoiding it. But, when I go to Portugal to study, people look at me and say: “He is not one of us, he does not belong to our group.” There, I gained clear conscience that I did not belong to the white Portuguese community.”

photo by Diogo Bento

photo by Diogo Bento

He ended up being involved definitively in the national liberation movement, doing what he describes as “a revolution between avoiding the sun and having a little mirror to wish for the palest possible skin colour until assuming a proud position of Africanity”.

Corsino recalls that “the colonial theory was very much based on racial relations”, but today thinks that Cape Verde is “one of the most integrated nations in the world”. The ex-minister of Education is among those who defend a notion of Cabo-Verdianidade in which everyone feel that they belong in a community. However, he disagrees with the idea that the archipelago is between Europe and Africa – “In terms of geography and sociological evolution, we are actually between Africa and South Africa, and in terms of humanity, Portugal is in its composition; this is what makes a singular case”.

The settlement of Cape Verde began in the 15th century and took 400 years from the settlement of the first island, Santiago, to the last, Sal, he clarifies. The use of racial criteria to impose political power was subtle, especially when compared with Angola and Mozambique, where the indigenous status existed, argues the ex-ambassador.

From the 18th or 19th centuries, the archipelago was presented as “what was later used by Gilberto Freyre to illustrate Luso-Tropicalism”, and Cape Verde was “evidence that there was no discrimination and not even justification to use the term ‘colony’”, he continues. “The colonial regime fell into the trap of the territorial integrity theory. From the beginning, Portugal chose to be different from the other European colonial empires and established an integrity from Minho to Timor. One strategy was to use Cape Verde within a global context of Portuguese empire: for a long time, Cape Verdeans were seen as some kind of adjunct to the colonial system, some kind of accomplice to rule over other colonies – in Angola e Mozambique, the Cape Verdeans are known as department heads, plantation workers, bosses. We are still paying the price, even today these memories are activated by our neighbours from west Africa in diplomacy.

Shock in Portugal

From 1998 to 2005, the sociologist Francisco Avelino Carvalho lived in Portugal thinking that he would finish a course on a Friday and return on Saturday. Nonetheless, he discovered Lisbon and ended up staying. Now 45 years old, Francisco Carvalho says that the racial questions in Cape Verde are not problematic nor central.

In fact, the opposite is true: there are all the deployable ingredients for the Cape Verdean society to be revanchist because the colonial system was an enormous violence, but, he defends, it managed to “overcome these historical conditionings” and develop social relations between different groups that “are not contoured by race”. “For me, the separation of the two groups, sampadjudo and badio, deserves far more attention than the racial questions in Cape Verde. The way perceptions are construed can bifurcate into much more complex processes.”

Enric Vives-Rubio

Enric Vives-Rubio

It was not in Cape Verde but in Portugal that the Communities general-director discovered that “he was dark, black” – just like Corsino Tolentino, years before. “In our way of seeing the world, in our mindset, the racial problem is not obvious. In Lisbon, we feel that racial differences are important and are structural elements of the logic of people’s reactions in certain contexts.” However, he had not expected what he witnessed in Portugal, such as “a racist Portuguese changing to the other side of the street when seeing that he was walking towards a black person”; sitting on a bus and the place next to him being the last to be taken; stereotypes that certain negative characteristics are associated to skin colour. “Arriving in Portugal, I realized that there was a divergence between my perception and what I find.”

What was, then, in the Cape Verdean society that encouraged him to imagine a Portugal that does not exist? Luso-Tropicalism avenged itself in Cape Verde? “What could have happened was that we did not reflect seriously on this past experience, imposed by the colonial system.”

For him, mild colonialism does not make sense, nor does subtle racism make sense – “merely playing on words”. “For the one who speaks, it is mild and subtle; but it can be the worst form of violence for the individual that is the object of the discourse. The degree of subtilty or violence is tremendously subjective and has to do with what people feel.”

Despite being a fundamental question, racism is not discussed in school, he says. And it should. Or worse still, we dismiss questions like the use of racial categories by the colonial system and the association of Africans with racial preconceptions – this took, in many cases, the detachment of the Cape Verdean identity from the African continent.

Besides, a survey demonstrated that Cape Verdeans mostly do not think that they are Africans – and, of these, many are from the windward islands, he points out. “It is tremendously ridiculous that a Cape Verdean thinks that he is not African – and there are many who share this opinion. This has to do with preconceptions imparted from the colonial period; especially the idea that an African is one that is rough, violent, out of place, incapable, selvage.”

Geographical limitation

A world-renowned plastic artist, today also a legislator of the MpD (Movement for Democracy) party, Abraão Vicente (1980 -) created recently a series of paintings inspired by the idea of passport. “Our document indicates where we can go, who we can be and what expectations we can have about ourselves”, he explains. For various painting he borrowed his friends’ passports and used his own to serve as a metaphor for what so many Africans are passing through today. “I see racism in the limitations that arise from you being where you are; it is more than just the colour of your skin”, he affirms.

His creative works reflect his understanding that racism is also a bureaucratic challenge that limits access to geographical territories to people “that would live in equality of circumstances with those already there”. He studied in Portugal and only felt that he was a foreigner when he needed to renew his visa or show his documents. He ended up acquiring the Portuguese nationality, through his grandparents, to avoid any further stress. “I have double nationality, but I have never felt that I represent Portugal. My nationality is also a bureaucratic question, it was almost a revenge for all the difficulties that I encountered.”

We are in the balcony of his apartment in Praia, a relatively new building to where he moved recently with his wife, the singer Lura. On the walls of the home are her works and posters of concerts given by one of the greatest music stars of the country. “Cape Verdeans claim that they are not racist, we build our miscegenated identity since the Claridade movement. This, however, is a false question knowing the social dynamics of Cape Verde and the way we relate to one another. Despite being supposedly mulattos, and not being a country of dark and black people like other Africans, Cape Verde does not approach the racial question as a skin colour question, for it is intimately related to the exercise of power and to political power. There are dark-skinned people who do not consider themselves black, but rather culturally white. There are islands like São Vicente and Fogo where this is clearer. When a Cape Verdean talks about himself or herself, he or she always recalls the white parent instead of the black parent.”

In social relations, it is noticeable that paler-skinned people are more well accepted – in institutions, in job applications… On the other hand, he criticizes, people from the interior of Santiago, darker, are discriminated. “Power filters out the black in the end. Ulisses Correia da Silva, president of the municipality of Praia, is the first black Santiaguense to run for prime minster. All the others were mixed, mulattos.”

These distinctions permeate family relations, most big families presenting themselves as descendants of Portuguese, he analyses. “The black Cape Verdean does not exist. We anchor our family tradition entirely to the Portuguese surnames. Before independence, the major families were Portuguese. After independence, there was another means to consolidate power, those families that participated in the movement for independence.”

He, a mulatto, light-skinned, also felt black when he departed for Portugal to pursue Sociology, he highlights, even “in Arts, he was only invited to exhibitions of African artists”, filling the Cape Verdean quota. “The label was unnecessary – an artist is an artist. The Lusophone construction, the idea that we inherit something, is based on assumptions that are too fragile for us minimally informed citizens. Our relationship is always intermediated…” Looking at the other Lusophone African countries, Abraão Vicente observes: “As a nation, we retain this nostalgia – a little idiotic – that we are closer to Portugal than others because we are light-skinned, mulattos, and do not have a truly deep African culture.” This “is a mere illusion”, though.

Two years ago, he wrote a book, 1980-Labirintos, in which he says specifically that “to be African in Cape Verde is a taboo”. Complete, but for this: “Certainly, I am African because our lives are under real influence of Africa, much more than of the European Union. However, it would be an error to say this because when I head for the street, I see that we are supported by Europe – all the projects are financed by European cooperation.” At the same time, he doubts that miscegenation sells today, “pitching that we are somewhat European and somewhat African”: “Neither Europeans nor Africans buy into the idea: then, Cape Verde is at crossroads, to assume Cabo-Verdianidade not as a historical construct based on Cape Verdean literature, but embrace music genres like batuque, funaná.”

The Stereotypes about Africans

The Sucupira market, in Praia, gather many African immigrants. It is a closed space with great buzz of people. There is all one can ask for in the narrow corridors – clothes, trinkets, shoes, perfumes, incense, herbs, fruits. African multiculturalism is in action as women in traditional attire from different regions sell African food ingredients – dried fruits, chilli, maize, cassava, sweet potatoes, beans, yams, green plantains – next to Anglo-Saxon branded tennis shoes and women in jeans and minidress.

photo by Miguel Madeira

photo by Miguel Madeira

In 2009, the anthropologist Eufémia Vicente Rocha published a thesis about xenophobia and racism in Cape Verde. A part of her research was conducted in Sucupira. She studied immigration from the African continent, on the increase, and during her research she was confronted with questions of sexuality and racialization. Regarding African immigrants, Cape Verdeans comment: “They have very big penis, a hallucinatory sexual performance to the point of hurting women, destroying uteruses and transmitting diseases.”

In her research, it became gradually clear that, for their identity, the Cape Verdeans imagine superiority to other Africans, reclaiming therefore rapprochement towards Europe. This was in part instigated by the colonial system built on racial distinctions, she highlights. “When the elite and the Claridosos [protagonists of a literary movement since the 1930s that revendicated the right to an autonomous cultural identity linked to Cabo-Verdianidade] demanded special attention from the metropolis, referring to their administrative performance and strong presence in education, they wanted a special position, hence, this rapprochement with Portugal and Europe. The intention never was to cut ties with the metropolis, but to gain a special place. Also, of relevance here is the question of Cape Verdeans being Portuguese citizens and not indigenous like the citizens of the other colonies. The elite enjoyed this position and tried to benefit from it. The other pole, Africa, is moulded in western mythology: Africa of darkness, mystery, fantasies and fables. This is the Africa that intellectuals reject.”

The anthropologist herself had an experience that illustrated this relationship with Africa. When she started fieldwork, she was “wooed by two men”. In the house, which her mother built in the Tira Chapéu neighbourhood where Eufémia and her sisters live, her parents asked regularly how her research was going. And when she told them that she was wooed, she was told: “Manjaco, no” – Manjacos is how Cape Verdeans call continental Africans. “The possibility of us uniting with a Portuguese or Spanish is not bad, though. With an immigrant, I ruin my race. With a white European man, I preserve the race. In the case of black Cape Verdeans, certain topics are common, saying: ‘You are black but fine.’ Such are the racial distinctions produced by colonialism that are reviving today – evidence that whiteness is privilege. The colonial racial logics that we think were obsolete are reappearing.” Another example, Morabeza – the art of hospitality – “is all very well with the Portuguese, but not with the west African immigrants”. “Deep down we continue to believe that white people are cooperative, different from the west African immigrants that are here to argue with us, bringing with them numerous unresolved problems.”

Professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Cape Verde, where she teaches courses in Anthropology and coordinates the master’s programme in Public Security, Eufémia Rocha hears from the students “the same discourses of many decades”: The exceptionalism of the Cape Verdean people, miscegenation and the fact that, even when race is present, it is not talked about. “This exceptionalism is invented, forged. An elite of the 19th and 20th centuries had an objective with regards to the metropolis and engineered Cabo-Verdianidade: the proper way of being a Cape Verdean.”

A genetically racial society

Nardi de Sousa is 40 years old, as old as the independence anniversary, and studied, like many Cape Verdeans, in Portugal. She pursued a bachelor’s degree in Sociology between 1994 and 1999, and later completed a master’s in African Studies, both in ISCTE. In 2003, she went to Angola for “the school of life”.

She is in a classroom in the University of Santiago, which is a building located close to the sea, close to Ponta Temerosa. The windows are opened to let the breeze in. She talks about two prevalent myths in Cape Verde: the so-called miscegenation and relations with Africa, that affect not only the country internally, but also its external relations. She elaborates: “African ancestry is very important for us in order to restore the real role of Africa as a lighthouse of knowledge. Slavery as an institution was invented to deny agency and justify the marginalization of the continent itself”, she affirms. “The dilution of Africa” – also title of a book of the rector of the University of Santiago, Gabriel Fernandes, who was not available for interview for this reportage while we were in Cape Verde – “takes place in the academia and in social media; Cape Verde continue to portray Africa as a land of savagery and brutality, to the point that African countries look at Cape Verde distrustfully. This affects our relations with Africans and with Europeans. The Africans feel discriminated at times”.

photo by Adriano Miranda

photo by Adriano Miranda

Anthropological research of the 18th century “transmitted distorted and false knowledge”, coinciding with the propagation of the evolutionist theory that defended that “the Europeans were the ultimate invention of nature and the Africans were selvage”, she notes, and there are still vestiges of this today. “A mentality was formed, and people sought to embody European traits.”

Cape Verde imagined a story wherein miscegenation started on the archipelago and this was “somewhat the result of Portuguese historiography”. Afterwards “Cape Verde looks upon itself as the country that is most miscegenated in Africa” and “there we start the Luso-Tropicalist conversation”, that encouraged many Cape Verdeans to demand a different role in the colonial hierarchy.

photo by Diogo Bento

photo by Diogo Bento

Photographer and filmmaker, César Schofield Cardoso, 42 years old, is mulatto, with light eyes. Politically, he classifies himself as black. The exclusion, that echoes racial relations, prompts him to position himself that way and affirm his Africanity, “as a form of appreciation, equilibrium and diversity of who we are”. He is adamant about teaching the History of Africa. “We remind ourselves constantly that we are a genetically racial society, that Cape Verde was born from on racial relations – some, white Europeans, others, black Africans.”

The truth is that the narrative construction readily instrumentalizes Cape Verde to confirm Luso-Tropicalism and “the theory that the conviviality between the Portuguese and the colonized peoples were pacific, harmonious”. The Cape Verdean intellectual, since the Claridosos, are responsible for propagating this idea, for vindicating the Luso-Tropicalism discourse of racial harmony in Cape Verde. “However, we are realizing that this is not really the truth, especially because right now we are beginning to fracture. How sustainable is this social model based on antiquated racial relations? How can we contain a profoundly divided society with a small elite and a majority not able to fully integrate? How sustainable is this enormous social inequality?”

Racism in Cape Verde?

Asking a Cape Verdean if there is racism in their country, the answer is no. The sociologist Redy Wilson would give the same answer – “only if against foreigners”. Recently, like what happens in former colonies such as Angola and Mozambique, “a certain resentment” is beginning to surface because of the presence of the Portuguese, “on top of this, in a dominating position” – Portuguese that arrive with racist attitudes in Cape Verde. “I am not saying that everyone is alike, but there are many Portuguese who did not came from some community or space where there was some proximity [with the black population].”

But racism exist. “What many defend is that, with white privilege, black pride is needed to locate Africa in the centre. This is not racism.”

photo by Diogo Bento

photo by Diogo Bento

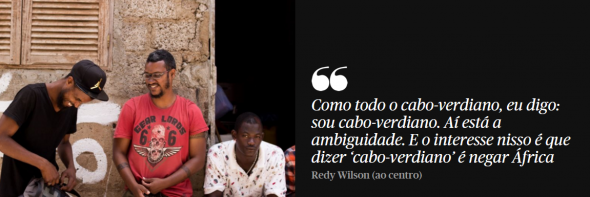

Studying gangs in Cape Verde, Redy Wilson says that there is a “big encounter, not just only any encounter, between the Portuguese and the Cape Verdeans”. He is also one fruit of this encounter: his family is half Portuguese, half Cape Verdean. Smilingly, he self-classifies racially as “a big problem”. “One time there were several students of the New University of Lisbon conducting an American-style questionnaire survey. There was a racial question and it was complicated. What race am I? I chose mulatto. There were Asian mulattos, African mulattos… Regarding the identity question, I am African. Having said this, I do not know where to put myself on the racial spectrum. What does it mean to be mulatto? There are many mulattos. In Praia, many people say that I am from Fogo because of my hair. Some people from the west African coast ask me if I am Indian. In Portugal, I am asked if I am Brazilian. They even asked me if I am Timorese. Then, you are everything or you are nothing. I was even told that I was too pale to be Cape Verdean and too dark to be Cape Verdean.”

But how does he feel? “Like all others, I say: I am Cape Verdean. Here comes the ambiguity. Interestingly, to be “Cape Verdean” is to reject Africa. We learned that we are Cape Verdeans, and this is how I grew up. I begin questioning what I learnt when I goes to Europe, I am not Cape Verdean, I am African. Once you pick your category and you pick African, you realize that you are not special.”

This is when he begins to dismantle the myth born from an anecdote about Salazar in which he was asked why Cape Verde did not have an indigenous status and he responded: “They are our children, special blacks.

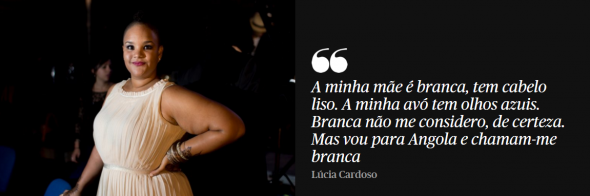

Lúcia Cardoso, director of the National Orchestra of Cape Verde, agrees that it is necessary to recognize that the archipelago is a melting pot of people from Eurasia, Middle East, of different African cultures and ethnicities, which is plainly visible in the appearances of Cape Verdeans.

photo by Diogo Bento

photo by Diogo Bento

At 32 years of age, she is also a singer, professional makeup artist, stylist, model. She says: “We are a musical nation, but we do not have infrastructure, not even schools to promote this – we have some 20 music festivals that are becoming commercial events. There is also resistance to music education and the orchestra [National Orchestra of Cape Verde] represents all that”, she explains.

Consciously African, unconsciously European

Lúcia Cardoso defends a slightly different view of Africanity. Cape Verdeans reject Europe consciously and reject Africa unconsciously, she says. “This is how it goes: We are not Europeans, we want to return to our roots – proclaimed aloud for others to hear. I call it, therefore, the “conscious reaction”. However, unconsciously, we desire straight hair, the finest possible facial features and what is considered beautiful, the beauty and living standards are typically west European”.

As for the discourse of returning to African origins, she thinks it is too superficial, because in reality “we do not even know Africa, how many countries there are, how they are divided”. “We say that we are Europeans, but for certain we do not want to be African, we suffer the colonialism syndrome. This is clear in Cape Verde. Centuries of intelligent colonial rule made us feel that we are foremen.”

It is very worrying that Cape Verde does not want to be connotated with Africa, she points out. Even the revitalization of some African materials, like fabrics, is, for her, “a little futile”, a trend, “not addressing the real problem”. Instead, we should be learning, for example, the history and symbolism of the patterns and prints used in the fabrics. Used to dealing with children, she is chocked by the European beauty standards and the contempt for African phenotypes, subtle things like the hair and the shape of the nose, but which “have huge, really huge impact on the lives of people”.

Looking into her eyes, there is some tinges of Asian influence. She is light-skinned. She says that her hair, now scrapped, turns blonde in the summer. Lúcia considers herself “black, whatever it means”, because she grew up in Cape Verde. “This is cultural, it has to do with feelings. My mother is white and has straight hair. My grandmother has blue eyes. White I do not think I am, of course. But when I go to Angola, people call me white.”

Relations with Africa are more than just racial or social. Cape Verde recently resumed commercial relations with the Economic Community of West African States, says César Schofield Cardoso, and this follows the imposition of special partnership with the European Union. “From social, cultural and economic perspectives, we do not prioritize the African economic space.”

photo by Miguel Madeira

photo by Miguel Madeira

He takes issue with the Eurocentric representations of Cape Verde, which ignore the existing theoretical production in these countries and the autochthonous narratives. A relationship of equals between Cape Verde and Portugal “is far from being a reality”, he concludes. “This is because the two countries have a complicated experience with colonialism – one as the colonizer, and the other the colonized. It is a debate difficult to settle, and naturally difficult to normalize. I believe that there is a will to develop economic and political relations – but are our social relations tranquil, healthy? Is the Portuguese society at peace with its Africanity, with its black population? Does Cape Verde treat the Portuguese tranquilly? From empirical observations, I say no. Mutual knowledge is very much lacking.”

The Cape Verdean society continues to live profound traumas of slavery, colonialism and racial violence. And the result? “There is no catharsis, but oblivion.”

Originally published in Público on 3 January 2016