Fragments of a new history - Zanele Muholi

The African continent for a long time was totally overlooked in the annals of the history of photography. Indeed, Africa only appeared timidly on the international horizon or rather to arouse certain interest in the West around the early 1990s. Among other important events of the time that contributed towards this growing interest figures the African Photography Biennial in Mali, also known as the African Encounters of Photography. This cultural event has, over the years, become one of the most important meeting points for African photography, enabling professionals from the whole continent over, as well as from the African diaspora, to sow their images and broaden the international visual landscape.

It was precisely that framework that gave rise to this collection that wishes to concentrate on the gaze of some of the women participating in the biennial. Our collection has two main objectives: firstly, to forestage African photography on the global scenario, in other words, to make it part of the whole and not merely consider it as part of the rest; and, secondly, to act out the will to endow African women photographers more visibility. This collection aims to break down the barriers of this double invisibility by looking at the narrative constructs of these women and thus multiplying the existing ways of seeing in an attempt to broaden and enhance our own perspectives.

It was precisely that framework that gave rise to this collection that wishes to concentrate on the gaze of some of the women participating in the biennial. Our collection has two main objectives: firstly, to forestage African photography on the global scenario, in other words, to make it part of the whole and not merely consider it as part of the rest; and, secondly, to act out the will to endow African women photographers more visibility. This collection aims to break down the barriers of this double invisibility by looking at the narrative constructs of these women and thus multiplying the existing ways of seeing in an attempt to broaden and enhance our own perspectives.

If, as Susan Sontag said, photography offers a new grammar of seeing 1 we believe that in order to enrich our present photographic vocabulary we should incorporate the oeuvre carried out by African women photographers. It may be true to say that as of the 1990s, many countries focused on disarticulating their narcissistic visions of the world, timidly grafting new fragments in this story written with light. But it is equally true to say, that a scarce few, a mere handful in fact, tried and are still trying to open up the frontiers of photographic language, by integrating the perspectives of both men and women and their peculiar visions of the world.

We are talking about visions and not “other” visions because African viewpoints have to be mapped in the world of photography without uttering commonplaces about photographic language or persisting on recurring stereotypes. If we are to truly appreciate the multiplicity of discourses and viewpoints afforded us by each and every one of the photographers, we should basically try not to reconstruct otherness once again and avoid objectifying and labelling a whole continent and its various peoples. We should plunge into history and try to understand the specific context that gave rise to each and every image. We should understand that cultural identities are not fixed, eternally suspended “in some essentialised past, they are subject to the continuous ‘play’ of history, culture and power.”2. Only by breaking down these constructions will we be able to move away from these simplistic deductions.

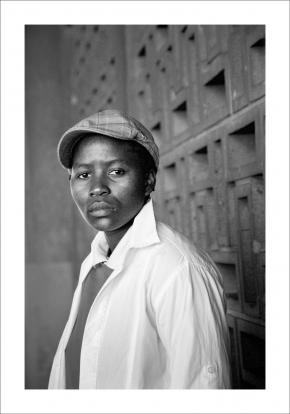

Thembi Nyoka, 2007. Zanele Muholi.

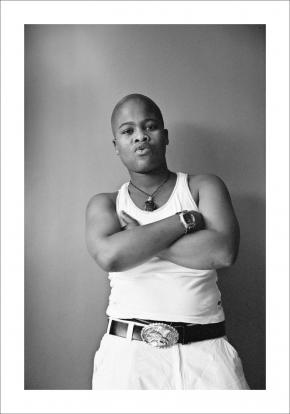

Thembi Nyoka, 2007. Zanele Muholi. Amogelang Senokwane, 2009. Zanele Muholi.

Amogelang Senokwane, 2009. Zanele Muholi.

The reality is that the men and women of Africa have rewritten their stories and history in their own words and images. This is the case of the South African photographer Zanele Muholi, our opening photographer in this collection.

The work of Muholi is fully in line with the objectives previously sketched in that the photographer is not only a female activist but also, to quote Muholi herself, a “visual activist”. Her fight and permanent political commitment has been towards giving visibility to the black community of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transexuals, and Intersexuals, something that they do not possess at present. Muholi not only belongs to this community but fights for it and looks at it from the perspective of a framework that gives coherence to her identity and to which she feels emotionally linked. She therefore manages to break down some of the stereotypes through her images, to do away with the fixed clichés that persist not only in the West but also in her country, the young democracy of South Africa, and throughout the African continent as a whole.

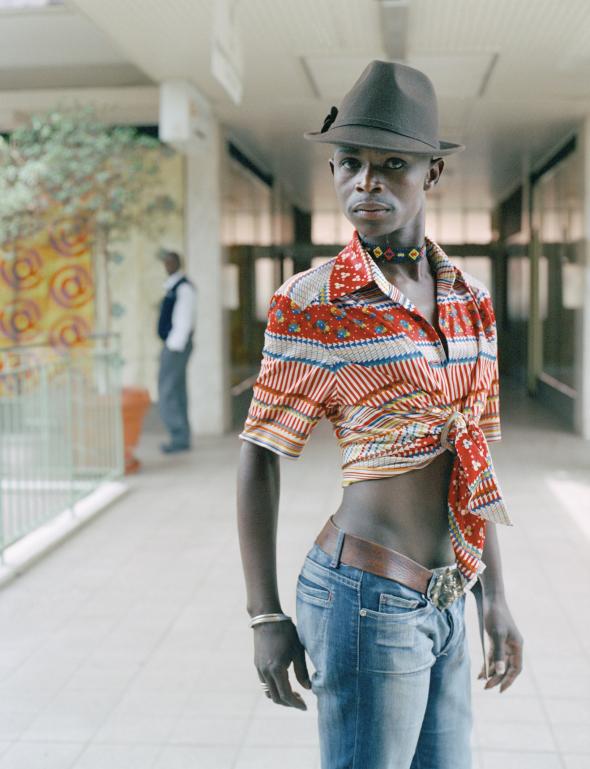

Muholi’s images offer us upfront personal portraits of women, black, lesbian, South African or other; women of all social backgrounds, showing us that this community does not possess one but a multiplicity of identities. She allows us to view a whole series of individuals close up, all of whom are volunteers and share a close relation with the photographer, human beings who come from different political, economic and social strata within their respective countries, and who are, who live, but who are excluded from the official history of their countries, as Muholi decries.

This is one of the major battles of this photographer: to defy the existing hegemony by rewriting a visual history as yet dominated by the heterosexual ethnocentric patriarchal vision, and which is perpetuated through the gaze and mindset of the male heterosexual, a world in which black lesbians are still labelled as “others”.

Martin Machapa, 2006. Zanele Muholi.

Martin Machapa, 2006. Zanele Muholi.

The cause emblazoned by Zanele Muholi with respect to the LGBTI community should be contextualised within the framework of the post-apartheid South African society to which the artist belongs. This is a society in evolution, in transformation, where a new generation of people like Muholi are fighting to overturn the established order and to seek out new forms of representation. Zanele Muholi, born in a township, to a working-class family has always fought for her right to live the life she chooses as a black lesbian in a country which has moved from violent anti-apartheid struggles to reconciliation with the oppressive forces in building a democratic transition. It is in this society that Muholi grew up. From an early age, she fought in human rights movements, then as an activist for the lesbian cause and afterwards embarked on photography after taking a course in the Market Photo Workshop, a school set up by David Goldblatt at the end of the 80s and which arose in response to apartheid, training young photographers who had been excluded from the traditional education institutions of the times.

The favourable climate that she found in the school led her to develop what she calls “visual activism”, taking photography as an act of militancy and alerting the world of the triple exclusion experienced by South African black lesbians who at the same time must fight against racism, sexism and patriarchal society. This multiple discrimination is more than apparent in the images where Zanele Muholi portrays women who have undergone what are known as “curative rapes”, crimes performed on lesbian women to “cure” them of their sexual “disorder” and put them back on the “right” heterosexual track. Muholi actively condemns this but, more importantly, and that is where her photographs are particularly powerful, she does not attempt to portray the women as victims but rather as active individuals. The value of her work relies in this will not to objectify the person portrayed, but subjectively documents each human being offering an incredible archive of the myriad of different perspectives of these women’s lives. They are portrayed individually, each with her own unique identity, as leading characters in this gradual and eventual reconstruction of a new visual picture of contemporary Africa and South Africa, at the same time as shattering myths such as that homosexuality is not an African reality but something imported from abroad.

In the whole of Africa, the idea still persists that homosexuality is a curse brought by the white man from the West and in many countries it is still fiercely persecuted. In the case of South Africa, and although the South African Constitution of 1996 is considered to be one of the most “progressive” in the African continent with sexual rights protected, heterosexual preferences are still privileged over the rest. Meanwhile, the West, obsessed as it is with the false image of “the authentic Africa”, cannot conceive of the idea of two black women in love as this is something that simply does not fit into their imagined construct of the continent.

However, her documentary work of piecing together the history of these women, her women, in pictures, reinterpreting their and her own experiences is not a mere register of their everyday struggle to fight bravely against all odds, to overcome the humiliations, losses and hurt experienced, the inner and outer scars left by life’s tribulations, but is rather about the love that inhabits each and every woman portrayed. Muholi’s work brims over with sensitivity, intimacy, raw sentiment and is fundamentally indicial. She unveils their lives, her life, sharing their moments of happiness, of complicity, honouring the relationships they live, piecing together and multiplying the fragments of a history that is written day by day.

The work of Zanele Muholi together with the images of the other photographers who will be part of this collection, are “fragments [that] can be pieced together, that overlap […] privileged lines of poetic licence that at one and the same time are captured and abruptly isolated from the disorder of the private language of sentiment.” They are “the history of this prodigious growth of stars.”3

MASASAM. Proyectos de Comisariado Sandra Maunac and Mónica Santos

- 1. Sontag, Susan (2008) On photography. Spanish Edition in Nuevas Ediciones de Bolsillo, Barcelona. p.13.

- 2. Hall, Stuart (1990) “Cultural, Identity and Diaspora”. In: Identity. Community, Culture, Difference. Ed. by Jonathan Rutherford. Lawrence and Wishard, London. p.225.

- 3. Benjamin, Walter (2011) A Brief History of Photography (Breve historia de la fotografía). Casimiro libros, Madrid. p. 59.