Black, between painting and history

Can a white, European man represent a black, Afro-Brazilian man? This question, asked by António Pinto Ribeiro in 2006 (1), could have been the epigraph for Noir. Entre Peinture et Histoire [Black. Between Painting and History], recently published in France. The book takes us on a journey through European painting from the fifteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, to discover how white European painters and their patrons understood and represented black people.

Bonheur d’Amour Prussien | 1890 | Emil Doerstling

Bonheur d’Amour Prussien | 1890 | Emil Doerstling

The question of the representation of black people in Western art is not new. It has been asked consistently since the 1960s, starting with the pioneering research driven and sponsored by collectors Jean and Dominique De Menil, which led to the cataloguing of some 30,000 images, drawings, engravings, paintings, sculptures and photographs. This work became the basis for the publication of several abundantly illustrated volumes, and for a database, available online at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research. However, unlike in the United States and the Anglo-Saxon world, in France and other Western European countries there was for a long time scant analysis of the representation of black people in European painting. Prior to the 1980s the existing bibliography is scarce, and reveals a minimal interest in the theme. In 1969 Ignacy Scachs published The image of the black man in European art [L’image du Noir dans l’art européen] in which he makes a first approach to these questions, but monograph length studies or catalogues are practically nonexistent. This gap was the starting point for Noir. Entre Peinture et Histoire.

The authors, Naïl Ver-Ndoye, of African heritage, and Grégoire Fauconier, of European heritage, are both teachers in secondary education. They were confronted with the lack of information on the representation of black men and women in European painting, which led them to very direct and immediate questions: who were the people represented? What were the motivations for representing them? And why did black people in European painting rarely have individualized identities? These are questions which might appear simple but are in fact profoundly complex. As Jean Genet asked, in a question that the authors put on the first page of the book: “Qu’est-ce that c’est donc un Noir? Et d’abord, c’est de quelle couleur?”(What therefore is a black man? And before anything else, what colour is he?).

Over the course of four years, the two teachers studied around 5000 European paintings depicting black people in the most varied contexts. They have selected 300 for Noir. Entre peinture et histoire. The book, clearly designed with teaching in mind, is structured in a simple and accessible way, addressing a wide range of audiences, from layman to curious observer, amateur, student or specialist. Through a varied selection of paintings, with detailed iconographic descriptions and exegesis, the reader is presented with a previously almost anonymous and “invisible” presence in the History of Art (notwithstanding the fact that from the 14th century European painters – including the most widely renowned – have represented people of African descent). 3 memoirs.ces.uc.pt One of the most interesting aspects of this book is its simple, pragmatic and objective approach to the theme, which nevertheless remains both sensitive and multidisciplinary. Throughout the history of painting there runs a thread of analytical and reflective work that deals with the contexts in which people are represented (in this specific case, people with black skin), and with these people’s identity and history. The authors follow a transversal approach, without pre-conceptions and fixed ideas. Attentive to the inherent problems of colonization, with its powerful reverberations in the present, they do not limit themselves to themes such as slavery, the occupation and exploitation of Africa by Europe, or the dominant-dominated / white-black relationship.

On the contrary, they try to lay out objectively how, and through what frameworks, European painters have represented black men and women. The key theme that emerges across the five centuries of works is how art, particularly painting, relates to hegemonic social prejudices and mentalities. All the works are by European painters, largely from precisely those countries that colonized the places of origin of the Afro-descendent people represented. Through the representation of black subjects, all the pieces, whether simple portraits, historical narratives or religious or allegorical scenes, raise questions of mentality, knowledge, identity, memory, prejudice, the relationship between dominant and dominated, colonization, slavery, religion or beliefs. The images offer traces, too, of how Europeans thought about, interpreted and accepted the emancipation of black people. Of course, the iconographies at work are inseparable from the history of painting itself, which from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries was carried out essentially for an elite who themselves conditioned the forms of narrative and representation. The works have been organized into 10 themes, which correspond to the 10 chapters of the book: Allegory of a Territory, Religion, Body, Slavery, Political Figures, Domestic Life, Talents, War, Everyday Life and Black Presence. In the broad scope of this thematic range we find reality and fiction, the telling of stories and the discovery identities. In their description of the works, interpretation of iconography and multidisciplinary reading the authors open space for reflecting on cross-cutting questions. These questions are inherent to the European gaze on Africa and the rest of the colonized world, and to the relationship between white people and black people. They arise, too, in the relationship between painting itself and the social and cultural context in which European painters and patrons were interested in the representation of black people. The writers have made challenging and interrogating openness to ‘the other’ one of the central objectives of the book, and this theme plays out in each painting’s description.

They also wanted to demonstrate, through the book’s structure and the selection of images, that parallel to this history of racism there are examples that “tear down the edifice of intolerance” and breathe life into a more considered and contextual vision of the history and complexity of human existence. Some of the portraits illustrate this proposition. The history of Ayouba Diallo, for example, is included in the chapter on Slavery. Painted in 1733 by William Hoare of Bath, Diallo was born in the early 18th century and was a cultured man, originally from Senegal. A black African, he had himself been a slave trader, and was then abducted and sold as a slave and eventually taken to work on a plantation in the United States. Caught up in many escapades and misadventures, he ended up being bought by the African Company (one of the pillars of the slave trade) and sent to England. There, through his culture and his linguistic skill he attached himself to London elites, who undertook to protect him, contributed to buying his freedom and helped him to return to Senegal.

This story is one of many that emerge from the authors’ research to show how people’s life stories, whatever their skin colour, are intricately imbricated in the most paradoxical of circumstances and interests. The book takes up the task of making an objective contribution to knowledge of European and African diversity and identity, and also to promoting Art as a means of access to History. The two teachers had in the front of their minds the many young students of African origin who they come across every day and who find little connection with Western art. One of their aims was to bring students closer to art, to show’s painting’s relevance through the timelessness of its themes, emotions and situations, which can be understood by all, regardless of social contexts. Many of the chosen works from previous centuries, such as the impressive portrait “Le garçon noir” (the black boy), painted in 1844 by William Lindsay Windus (1822- 1907) take us directly to contemporary problems. The painter portrays, with deep intensity, the solitude, resignation and sadness of an anonymous child, dressed in tattered clothes, wandering the streets of Liverpool after clandestinely crossing the Atlantic. Before opening up the question of Art and History, the authors frame the problematic of the identity and representation of black people along a number of vectors.

They begin with the sensitive question of nomenclature and designation, which over the course of five centuries has been through many iterations, many of them with pejorative connotations, but all revealing, even today, the challenge posed by naming the appearance of non-caucasian, ‘black’ people, through colour (Être noir - page 6-7). It was precisely this difficulty that has given rise to a very diversified lexicon that varies according to colonial regions. This issue is specifically treated in relation to the French language and Frenchspeaking colonies. The authors focus in particular on the issue of colour, by summarizing linguistic issues that communicate the discomfort that comes with identifying and designating skin colour.

They do not limit themselves to people of African origin but emphasize that the guiding line of their research is the representation of black people in painting. For the painter, the fundamental question was not lexical, but anatomical and chromatic representation (also briefly discussed: Noir en peinture - page 9). This manifested in questions such as how to choose and obtain pigments for the broad colour range of the skin, the study of light on black skin, the gradations of tones across different parts of the body and studying the configuration of faces. All these themes are presented in a simple way through brief summaries, but always in order to open a space for deeper debate and development. For example, they note the duality that underpins the concept of blackness which “contrary to what is often thought, is not just a question of skin […]”, but one of culture and experience. The albino of African origin does not see himself, nor is he seen by others, as a white man, but as a black man. In the selection of paintings here the problem is illustrated, for instance, in the portrait of the young Benedetto Silva d’Angola, painted in 1709 by Antonio Franchi (1638-1709), who is identified in the painting as a “White Moor” and son of a “black father and mother”. It appears too in stories from antiquity, such as that of Tejeras and Claricleia, written by Heliodoro de Emeso in the Third Century. Claricleia is the daughter of the king of Ethiopia, who is black, but Claricleia is born white. She desperately seeks to prove her lineage by showing a patch of black skin on her arm. This story of a search for identity inspired Karel van Mander (1606-1670) to make a set of paintings illustrating several chapters and imagining an entire exotic universe of Ethiopia and its inhabitants. The link that connects all the ten topics discussed in the chapters of the book is the representation of black people, but this does not limit them to merely illustrating a little known part of Art History.

Rather, the breadth of themes and the links between the analysis of iconographies, people’s history, narrative framework, historical context, allegorical, truthful or imaginary, consolidate the strand of Art History that emerges in syncopation with the strand of Social History. They show the concrete ways that the sphere of representation relates to the History of mentalities. It is through art, and the diversity of modes of representation, that the reader discovers how, over time, the perception of the “other” has changed … or has not. Between the fifteenth century and the early twentieth century, European painting of black people by white artists is largely of anonymous figures, at the service of the European. They are figures imagined by painters and placed in exotic scenes, or in the kinds of allegorical representations of the African continent which appealed to many painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Rarely are Africans or black people painted with their individual qualities in mind.

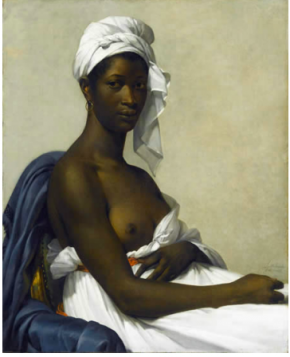

Iconographic explanation and critical analysis are intertwined in this book, connecting social history with contemporary themes. In the chapter Allegory of a territory, the section ‘France in the centre of the world’ reflects on the problematic of colonization, the subject of intense contemporary debate. For example, in the paintings of Louis Bouquet, made in 1931, colonization is represented as an idyllic mission, allowing Africans to benefit from French culture and civilization. The explanatory text guides the reader to critique the paintings so as to render perceptible the way in which their iconography constantly obscures the violence and exploitation inherent to colonization. One of the works, ‘Apollo and his Black Muse’, shows an absurd thematic mash-up, of the Greek god Apollo playing his lyre, surrounded by naked Africans dancing in the midst of wild animals. The image corresponds to the stereotype of the ‘happy savage’, famously presented in the colonial exhibition of 1930. In the painting ‘Recollection of the Museum of the Colonies’, also by Bouquet in 1931, the architect of the museum, Portrait d’une négresse | 1800 | Marie-Guillemine Benoist and its decorator are seen with figures from French ‘high society’, and accompanied by a naked black woman, stripped of any attributes of the European idea of “civilization”.

Portrait d’une négresse | 1800 | Marie-Guillemine Benoist Throughout the various chapters of the book, the paintings are points of departure to deeper discussions beyond the history of painting, which pose new questions. In the chapter on Religion, the portrait of Abbé Moussa, painted in 1847 by Pierre-Roch Vigneron, is the catalyst for exploring the debate over the acceptance by the church of the election of black people to ecclesiastical positions. The premise was put forward that, as ‘natives’, black people would more easily evangelize to ‘natives’. As part of the colonizing project, Senegalese children were sought out in order to educate them in seminaries and produce an ‘autochthonous’ clergy in the colonies. The chapter on The Body explores how European representations of African people oscillated between fascination with the black, sensual, vigorous, muscular body and derogatory representations which figured the black body as an object, or as diabolical. The role of racial theories within projects of colonization emerges clearly in this chapter. The 1632 work of the Dutchman Christiaen van Couwenbergh, ‘The abduction of the black woman,’ shows a black woman raped by three white men. It is a rare subject in seventeenth-century painting, especially in a large work. The book’s simple, concise text draws attention to a whole field of reflection on the human condition, injustice, violence and racism. Various works illustrate this chapter, showing divergent approaches to blackness and the body. Some show the confrontation between the black body and the white body in religious contexts. For instance, the representation of Bathsheba in the bath painted in the late 16th century by Cornelis Corneliszoon van Haarlem (1562-1632), shows her aided by a black slave and is one of the first African female nudes in European painting. Or, later, in romantic and exotic scenes such as the 1870 work ‘Turkish bath’ by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), in which the muscular body of the black slave contrasts with the anatomy of the white woman, or indeed in one of the masterpieces of the French painter Marie-Guillemine Benoist, the beautiful ‘Portrait of a Black Woman’, painted in 1800. Through 28 paintings depicting a variety of themes and made between the beginning of the eighteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century, the chapter on Slavery recalls how the relationship between Europe, Africa and America was deeply marked by the slave trade. The images portray the history of slavery, especially in the French colonies, until its abolition in 1794. Through two portraits, that of Ayouba mentioned above, and another of William Ansah Sessarakoo, painted in 1749 by Gabriel Mathias (1719-1804), attention is drawn to less well-known aspects of the slave trade, such as the intervention of black people within it. Both subjects of the portraits were slave traders, but, because of the colour of their skin, were also sold as slaves. Ansah, originally from Ghana, took after his father as a slave trader. He sent his sons to England to have a European education. In the Caribbean the captain of a boat in which he was travelling forced him amongst the other black people on board, and Ansah was sold as a slave. He remained a slave for several years until he was recognized by a merchant of his own ethnic group and freed. The collection of portraits in the chapter Political Figures broadens the book’s scope to hitherto less studied areas, such as the representation of black or mestizo political figures long before the contemporary era. The stories behind each portrait always propose new, manifold reflections. One of the oldest European portraits of an African-born nobleman dressed in a Western style, painted around 1643, is of Dom Miguel de Castro, of Angolan origin. He was sent to Brazil to co-ordinate diplomatic relations with the Low Countries. More recent than that, the portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a congressman in Santo Domingo, shows the complex relationships between power and slavery. Of Senegalese origin, Jean-Baptiste was sold as a slave to work in the Dominican plantations. He managed to buy his freedom and joined the French army where he earnt money and accrued some power, after which he returned to Santo Domingo and himself became an owner of slaves. After the French Revolution and the abolition of slavery he returned to the island again, this time as a deputy to represent the black population. The chapter on domestic life stands out for the quality of its survey. There are pictures from the seventeenth to the beginning of the twentieth centuries, through which we can trace the presence in Europe of many young black people – bought, traded or exchanged as gifts – who ended up serving high society. Often associated with the exoticism of distant lands, and with the power that this exoticism symbolized, they are often represented with luxurious turbans, accompanied by a monkey or a parrot, or serving coffee from plantations cultivated by slaves. The chapters devoted to talent, war and daily life follow. In the chapter dedicated to war, the authors focus on Felix Vallotton’s 1917 painting ‘Senegalese Soldiers in the Field of Mailly’. Through this painting they address the problem of the countless African soldiers who died in France under a blanket of anonymity. They question the silence and general amnesia that has followed on the lives and deaths BLACK, BETWEEN PAINTING AND HISTORY 9 memoirs.ces.uc.pt of these soldiers. In the chapter on daily life, one of the most outstanding works is Emil Doerstling’s painting ‘Bonheur d’amour Prussien’, which depicts Gustav Sabac el Cher, a dark-skinned mestizo, and a young white woman with very pale skin and green eyes. The painter contrasts the colour of their skin with the expression of happiness that unites them. As elsewhere the image is the catalyst for other questions, in this case to recall, firstly, the apartheid that Germany imposed in its colonial empire and which led to the genocide of the Herero and the Nama in what is now Namibia. And, secondly, to draw attention to the ugly paradoxes of humanity: Gustav’s two sons were part of German army under Nazi rule. The chapter ‘Black Presence’, brings together a series of very diverse images from a wide spectrum of topics and times. Of the 27 works in the chapter, three seventeenth-century paintings of Lisbon stand out. Lisbon has been called the “most African city in Europe”: up to 1791, 400,000 Africans arrived in Portugal. In conclusion, Noir. Entre Peinture et Histoire, is situated between History and the History of Art. From the gaze of white, European painters, the book gives visibility to black men and women whose singular life courses remained almost always invisible and anonymous. Painting is the starting point for a retrieval of memory. Memories of people, experiences and situations that are inseparable from the history of colonization that marks the relations between Africa and Europe and that still today resonate deeply in African and European mentalities, and still provoke controversial sentiments. Maybe that’s why the authors had so much trouble finding a publisher for this work (they contacted more than 30 publishing houses). The term “Black” was considered a problem. The editors thought it was not ‘a French theme’, that there would be no public interest, or that “the French public was not prepared” for the book’s revelations. The book was edited in 2018 by Omniscience, an independent publisher founded in 2005.

Portrait d’une négresse | 1800 | Marie-Guillemine Benoist Throughout the various chapters of the book, the paintings are points of departure to deeper discussions beyond the history of painting, which pose new questions. In the chapter on Religion, the portrait of Abbé Moussa, painted in 1847 by Pierre-Roch Vigneron, is the catalyst for exploring the debate over the acceptance by the church of the election of black people to ecclesiastical positions. The premise was put forward that, as ‘natives’, black people would more easily evangelize to ‘natives’. As part of the colonizing project, Senegalese children were sought out in order to educate them in seminaries and produce an ‘autochthonous’ clergy in the colonies. The chapter on The Body explores how European representations of African people oscillated between fascination with the black, sensual, vigorous, muscular body and derogatory representations which figured the black body as an object, or as diabolical. The role of racial theories within projects of colonization emerges clearly in this chapter. The 1632 work of the Dutchman Christiaen van Couwenbergh, ‘The abduction of the black woman,’ shows a black woman raped by three white men. It is a rare subject in seventeenth-century painting, especially in a large work. The book’s simple, concise text draws attention to a whole field of reflection on the human condition, injustice, violence and racism. Various works illustrate this chapter, showing divergent approaches to blackness and the body. Some show the confrontation between the black body and the white body in religious contexts. For instance, the representation of Bathsheba in the bath painted in the late 16th century by Cornelis Corneliszoon van Haarlem (1562-1632), shows her aided by a black slave and is one of the first African female nudes in European painting. Or, later, in romantic and exotic scenes such as the 1870 work ‘Turkish bath’ by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), in which the muscular body of the black slave contrasts with the anatomy of the white woman, or indeed in one of the masterpieces of the French painter Marie-Guillemine Benoist, the beautiful ‘Portrait of a Black Woman’, painted in 1800. Through 28 paintings depicting a variety of themes and made between the beginning of the eighteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century, the chapter on Slavery recalls how the relationship between Europe, Africa and America was deeply marked by the slave trade. The images portray the history of slavery, especially in the French colonies, until its abolition in 1794. Through two portraits, that of Ayouba mentioned above, and another of William Ansah Sessarakoo, painted in 1749 by Gabriel Mathias (1719-1804), attention is drawn to less well-known aspects of the slave trade, such as the intervention of black people within it. Both subjects of the portraits were slave traders, but, because of the colour of their skin, were also sold as slaves. Ansah, originally from Ghana, took after his father as a slave trader. He sent his sons to England to have a European education. In the Caribbean the captain of a boat in which he was travelling forced him amongst the other black people on board, and Ansah was sold as a slave. He remained a slave for several years until he was recognized by a merchant of his own ethnic group and freed. The collection of portraits in the chapter Political Figures broadens the book’s scope to hitherto less studied areas, such as the representation of black or mestizo political figures long before the contemporary era. The stories behind each portrait always propose new, manifold reflections. One of the oldest European portraits of an African-born nobleman dressed in a Western style, painted around 1643, is of Dom Miguel de Castro, of Angolan origin. He was sent to Brazil to co-ordinate diplomatic relations with the Low Countries. More recent than that, the portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a congressman in Santo Domingo, shows the complex relationships between power and slavery. Of Senegalese origin, Jean-Baptiste was sold as a slave to work in the Dominican plantations. He managed to buy his freedom and joined the French army where he earnt money and accrued some power, after which he returned to Santo Domingo and himself became an owner of slaves. After the French Revolution and the abolition of slavery he returned to the island again, this time as a deputy to represent the black population. The chapter on domestic life stands out for the quality of its survey. There are pictures from the seventeenth to the beginning of the twentieth centuries, through which we can trace the presence in Europe of many young black people – bought, traded or exchanged as gifts – who ended up serving high society. Often associated with the exoticism of distant lands, and with the power that this exoticism symbolized, they are often represented with luxurious turbans, accompanied by a monkey or a parrot, or serving coffee from plantations cultivated by slaves. The chapters devoted to talent, war and daily life follow. In the chapter dedicated to war, the authors focus on Felix Vallotton’s 1917 painting ‘Senegalese Soldiers in the Field of Mailly’. Through this painting they address the problem of the countless African soldiers who died in France under a blanket of anonymity. They question the silence and general amnesia that has followed on the lives and deaths BLACK, BETWEEN PAINTING AND HISTORY 9 memoirs.ces.uc.pt of these soldiers. In the chapter on daily life, one of the most outstanding works is Emil Doerstling’s painting ‘Bonheur d’amour Prussien’, which depicts Gustav Sabac el Cher, a dark-skinned mestizo, and a young white woman with very pale skin and green eyes. The painter contrasts the colour of their skin with the expression of happiness that unites them. As elsewhere the image is the catalyst for other questions, in this case to recall, firstly, the apartheid that Germany imposed in its colonial empire and which led to the genocide of the Herero and the Nama in what is now Namibia. And, secondly, to draw attention to the ugly paradoxes of humanity: Gustav’s two sons were part of German army under Nazi rule. The chapter ‘Black Presence’, brings together a series of very diverse images from a wide spectrum of topics and times. Of the 27 works in the chapter, three seventeenth-century paintings of Lisbon stand out. Lisbon has been called the “most African city in Europe”: up to 1791, 400,000 Africans arrived in Portugal. In conclusion, Noir. Entre Peinture et Histoire, is situated between History and the History of Art. From the gaze of white, European painters, the book gives visibility to black men and women whose singular life courses remained almost always invisible and anonymous. Painting is the starting point for a retrieval of memory. Memories of people, experiences and situations that are inseparable from the history of colonization that marks the relations between Africa and Europe and that still today resonate deeply in African and European mentalities, and still provoke controversial sentiments. Maybe that’s why the authors had so much trouble finding a publisher for this work (they contacted more than 30 publishing houses). The term “Black” was considered a problem. The editors thought it was not ‘a French theme’, that there would be no public interest, or that “the French public was not prepared” for the book’s revelations. The book was edited in 2018 by Omniscience, an independent publisher founded in 2005.

VER-NDOYE, Naïl; FAUCONIER, Grégoire, Noir. Entre Peinture et Histoire. Ed. Omniscience, 2018.

________________ (1) Pinto Ribeiro, António, “Exposição como representação”. In Réplica e Rebeldia, Catálogo de Exposição, Lisboa 2016, pag. 9 ________________ Translated by Archie Davies Ana Paula Rebelo Correia has a PhD from the Université Catholique de Louvain (Belgium), where she also graduated in the Methodology of Plastic Arts. She is a researcher in History of Art with a special focus in the area of iconography, a research member of ARTIS and CLEPUL (FLUL), and a member of the Cultural Council of the Frontier Houses Foundation and Alorna. She has published several studies in the field of iconography.

FILHOS DE IMPÉRIO E PÓS-MEMÓRIAS EUROPEIAS CHILDREN OF EMPIRES AND EUROPEAN POSTMEMORIES ENFANTS D’EMPIRES ET POSTMÉMOIRES EUROPÉENNES memoirs.ces.uc.pt