The Elephant and Ulysses S. Grant

We decided to stick around for a beer at the end of a shooting day for the movie “The Hero” directed by Zezé Gamboa. We were on the Island of Luanda, where we had filmed from two in the afternoon to one in the morning. We stopped the car next to a stand, leaving the door open to keep listening to the pirated cassette playing on the car radio. In the group, the Angolans drink imported beer, Super Bock; the foreigners drink national beer, Cuca, each one savouring the exotic freshness of its own point of view while we talk in the shadow of a tranquil weekday dawn.

May beer never be absent at the times in which it is the only thing that suits the moment perfectly.

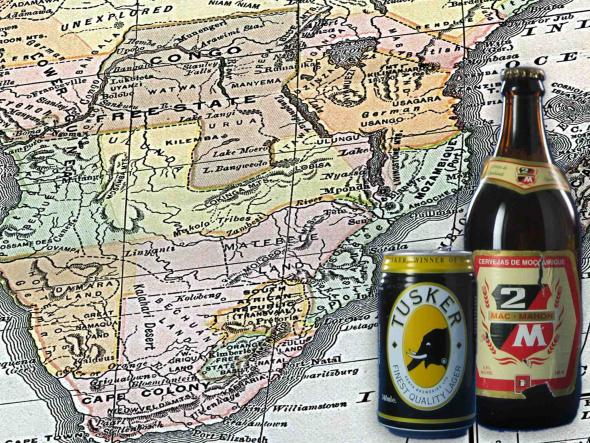

As it is a popular, highly consumed drink requiring few industrial resources, almost every country has national production of one or several qualities. There are endless brands and kinds of beer, some of them baptized after large or small historical events in Africa: dramas, comedies or tragedies, according to the exoticism of each one’s point of view.

Founded in Kenya in 1922, Tusker proclaims itself the first beer in Eastern Africa. One of its founders, George Hurst, was killed in 1923 by an elephant during a hunt. The protagonists of this event had different fates: George, the founder, vanished into oblivion; the elephant gave his name to the beer and his image to the logo. Tusker is the name for elephants with large tusks like the one on the label, the silhouette of an elephant over a yellow background: Tusker - Finest Quality Lager.

When I first saw the Mozambican beer 2M, the two M’s on the label were a mystery. I asked several times what those initials meant without getting an answer. In smaller letters: Mac-Mahon. It may be someone’s name. Read at the table of an esplanade in Maputo, the sonority is closer to a suburban healer than the name of a head of state. Appearances are deceptive. Mac-Mahon was President of the French Republic, and in 1875 he decided against the British expansionist plans to control Lourenço Marques’s harbour and the southern region of Mozambique in favour of Portugal. Many years later, in gratitude, Portugal returned the favour: Patrice de Mac-Mahon was immortalized on the label of the 2M beer, until today. In a design that goes beyond retro, a coarse red and white coat of arms with the family’s name, framed by fermenting wheat: 2M - Finest Quality Beer.

Following this logic of retribution, a beer named UG could have existed in Guinea-Bissau, for five years before Mac-Mahon’s decision, the North American president Ulysses S. Grant also favoured Portugal against the British pretensions over Bolama, the archipelago of Bijagós and the Guinean coast.

To History remained, without great objections, many of the borders that the Europeans used to divide Africa between themselves, as well as the labels of beers that end up on the table of any customer.

Over the years, I forgot the bureaucratic routine and waiting time implied in crossing the terrestrial borders of Europe. Having to pay attention to the days and hours to move between countries seems like a return to the past. Avoiding the ends and beginnings of school holidays. On weekends, calculating how to arrive before the lines, or else we’ll spend many hours waiting to cross the border between Mozambique and South Africa – from Ressano Garcia to Lebombo – that dividing line that Mac-Mahon insisted on keeping to counter the British hegemony in Southern Africa.

When the borders become congested, enormous lines of people form, step by step, to follow the procedures in the various counters of the frontier services, on one side and then on the other. Lines of cars, miles of stop-and-go, stop-and-go. All the documentation: passports, visas, filling out car insurance or the vehicle’s extensive form, money in both currencies to pay taxes and stamps. At this border, the hours have been lengthened, but not long ago it only opened from six in the morning to six in the afternoon.

While borders in Europe are not as widely opened as promised in the advertisements, they are incomparably simpler than the crossing of terrestrial borders in Africa. The slow, bureaucratic processes favour resorting to bribery to speed up procedures, discretionary rules, higher expedient costs for white people, limits on the quantity of products allowed to enter from the other side, or simply the endless queues and, worst of all, having to sleep “on the other side” if one arrives too late: border closed.

Some efforts to reduce the period in which the borders are closed have succeeded, economy and citizens grateful. But there are also borders on the African continent that are hopelessly closed—a consequence of disagreements with no solution in sight—while others close and open according their neighbour’s political equilibrium.

In a production van, the usual Hiace, we headed to the neighbourhood of Mavalane, in Maputo, where Wilson’s bar was. The actress Ana Magaia and I wanted to talk with him about working with us on an American production. In the group, the nationals drink imported beer: Sagres and Castle; the foreigners drink Mozambican beer: Laurentina and 2M. Each one savouring the exotic freshness of its own point of view while we talk in the light of an easy-going weekend afternoon.

May beer never be absent at the times in which it is the only thing that suits the moment perfectly.

Published in the magazine Fugas, part of the newspaper Público, November 2008.