Tarifa African Film Festival

The FCAT spreads knowledge about African film production by exhibiting a representative wide variety of audiovisual African works every year: from the classics to more innovative and recent films, from documentaries to feature length fiction films, from South Africa to Morocco and from Senegal to Ethiopia.

Last May, internationally acclaimed Guinean filmmaker Mama Keita commented: “the FCAT is a mirror facing Africa”. Similarly, the highly celebrated and Cannes-awarded Malian-Mauritanian filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako insisted on the importance of an African film festival like FCAT, hailing it as “a bridge that politicians never make”.

The FCAT is not just the only competitive African film festival in Spain, but it has become one of the biggest and most renowned film events of its kind both in and outside Europe. Offering €48,500 in prize money through 8 different awards, the festival in Tarifa embodies both an innovative cultural bridge - in which African films become the encounters between the two continents and their different cultures, and “a tool for knowledge, raising of social awareness and development”, as Mane Cisneros Manrique, founder and director of the FCAT, explains.

**

one part of the programme is called:

UTOPIA AND REALITY: 50 YEARS OF AFRICAN INDEPENDENCIES?

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Independence of 17 African countries, FCAT’10 offers a selection of African and non-African productions that explores, illustrates, questions and analyses this independence. There are films which talk about the life and ideas of figures like Aimé Césaire, Patrice Lumumba or Amilcar Cabral, or about the hope and dignity found after so many years of colonialism.

Simposium

1. THE REALITY OF AN ERA, TIME FOR HOPE - The weight of Heritage

The European colonization of the African continent was an incredibly quick phenomenon. European imperialism, based on exploration followed by conquest, turned the geo-political situation of the continent upside down in less than a century and a half. By 1900, Africa had practically been split and shared.

Doubtlessly, one of the heaviest burdens of colonization is the imposition of a territorial organization model on the entire continent. When the Europeans radically remodeled the continent, reconfiguring it territorially and transforming its socio-political organization, they burdened it with a load that it still weighs it today. (Despite their arbitrariness, most of the frontiers that were drawn are still in place).

The partition of Africa, divided into states, carried out according to rivalries between European powers, translated, no more and no less, into the territorial and linguistic division of an entire continent, projecting the differences that affected Europe and the colonial model chosen by each European State.

The colonial system was based on political domination and economical exploitation, and the colonial economical exploitation turned into the pillage of natural resources.

“The history of Africa’s relationships with Western countries has been a history of pillage; pillage of African labor, of its mineral and agricultural resources and of its land. Although direct slavery no longer exists, the three dynamic factors that trigger the struggles that will decide Africa’s fate continue to be the workforce, natural resources and land.” (J. Woods)

This organization was based on the exportation of raw materials to Europe in exchange for products manufactured in protected markets, the construction of roads, plantations, etc. Economical structures based on the asymmetric relationship between colonies and metropolis that, today, have still not changed.

As regards political domination, each European State had its own model, which, in turn, would deeply brand the future independent countries. But, above all, within this context stands the question concerning the imported model of Nation-State. A state that precedes the configuration of the nation, and that arises from exogenous colonial dynamics that African societies had no control over.

The explanation for the rapid decline and fall of the European empires must be sought for in the world events of the time. The international context is essential to understand this collapse: The Second World War proved that the colonial powers were no longer invincible and two new powers burst onto the international stage ready to help colonized people; but, above all, the process was driven by the will of the colonized people. The nationalization of the Suez Channel in 1956 was, without a doubt, one of the starting moments of this lengthy struggle, followed by the creation of the non-aligned movement. The dynamism of this movement in the sixties and seventies marks the zenith of the decolonization, but also stumbles against the contradictions of independency and power falling in the hands of the elite who depended on the West.

Historians usually speak of a “pacific” decolonization - with some exceptions - when referring to the African continent. (The cases we will study are examples of those exceptions). Speaking in general, it is a process without major conflicts, but we must differentiate the mechanisms used by each of the metropolis. Therefore, each former colony had its own form of decolonization (differences between the decolonization of British Africa, French Black Africa or the Portuguese colonies, etc.)

Macharia Munene. Professor of History and International Relations at the United States International University of Nairobi, Kenya. He is also International

professor on Conflicts in Africa in the International Master for Peace and Developpement at the Jaume I University in Castelló. He is the author, coauthor

and co-editor of numerous publications. He also regularly participates in different press media as commentator on the political situation of the African continent.

**

2. African Thought. The great ideological and political figures of Independence

It is not enough to study the context to understand the independence process; we must also analyze the “thinking process” of Africans during those years. We will only be able to really see the continent if we can discern its thought process. Only thus will we understand that African philosophy in those years was anti-colonial practice. So demanded Kwame N’Krumah: “Social revolution must have (…) an intellectual revolution. A revolution in which our thought process and our philosophy are directed towards the redemption of society.”

Therefore, to speak of the African thought process is to restore the fundamental elements of African philosophies, to speak of their great thinkers, of those men who tried to carry their thoughts into practice, into political action. Although we must also point out that the African experience was not monolithic. Africans on the continent and in exile found a common “language” based on the awareness of their collective entanglement in modern Western history, their being taken as objects and things by the West. They fought both as individuals and collectively, with pluralist and multi-sided methods, against the oppressive tendencies within the European capitalist culture and against the illegitimate colonial structures that squashed African initiativeson the continent.

Franz Fanon

Franz Fanon Leopold Senghor

Leopold Senghor

“Négritude”, a thought developed by Aimé Césaire and Léopold Senghor among others, renovated the resources and energies for a continuous fight against European degradation and corruption of Africans, both on the continent and in Europe. It is a movement that claimed dignity and identity for black people. In fact, with Senghor, who became the first president of independent Senegal, the movement steered towards a political stance that affirmed African values, although it was soon clear that his moderate stand did not leave any room for revolutions.

Pan-Africanism, a political, philosophical and social movement, was taken into the political arena by men such as N’Krumah. N’Krumah, the father of the independence of the country to be known as Ghana and considered one of the heroes in Africa’s battle to recover its dignity, and Jomo Kenyatta, who played a similar role in Kenya, were the spokespeople of this movement. The advocates of Pan-Africanism, who believed that the unity of Africans was the way to oppose the colonial forces, had the satisfaction of seeing the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963. Although this organization, now AU (African Unity), quickly disappointed those who believed in the possibility of a political unity on the continent that would have allowed them to resist imperialism’s attacks. So, although the anti-colonial fight united African political leaders, Pan-African utopia could not resist the “realpolitik” of their own interests.

Jomo Kenyatta

Jomo Kenyatta N’Krumah

N’Krumah

Another important factor during the independence period was that the political and intellectual elite sought to re-appropriate the past. Exalting the pre-colonial past was necessary to reinforce, and even plant, the feeling of nationalism, but, above all, for Africans to recover their pride and dignity and free themselves from European domination. Colonization went hand in hand with the denial of the African continent’s history. Frantz Fanon expressed it very clearly “Colonization is the shameless denial of the humanity of those colonized (…) It affirms that those colonized have no past history and that their history begins with the arrival of the European conquest.”1 That is why philosophers such as Fanon or Césaire insisted on the recognition of such fundamental notions as the historical fact that colonization existed. Césaire stated “(…) the primary interest of those colonized is to recover their role in history: to become a historical being once again. To deny the denial of their historic past and overcome the violence of being a mere object within European History.”2

Continuing with this subject, Fanon declared: “Decolonization is the genuine creation of new men (i.e., a new humanity). But this creation does not owe anything to supernatural powers; the “thing” that had been colonized becomes a man during the same process in which he is freed.”3

Amílcar Cabral

Amílcar Cabral

By following the thoughts of these intellectuals we can scrutinize some of the starting points of the postcolonial philosophy of the continent, we can understand how an African thinks, sees himself, how he positions himself regionally, locally and globally as a Man. However, by means of these philosophers we also discern some of the political justifications that the most charismatic leaders of the time used. For example, this is the case of Amilcar Cabral, the revolutionary leader of the so-called Portuguese Guinea, who, weapons in hand, fought against Portuguese colonialism until independence was achieved. An armed conflict based on the same arguments raised by Fanon. Cabral said: “We do not defend armed struggle (…) That is also violence employed against our own people. However, we did not invent it. It was not a decision taken coldly: It is a historical requirement.” As Fanon explained upon observing the inhuman behavior of the settlers, those subjected learn that they can only retrieve their freedom by unleashing their own wave of counter violence.

Mohamed Bahdon. Yibuti sociologist and expert in governability and political systems in the African Horn. He majored in Law, International Relations and Foreign Trade at the Toulouse I University of Social Sciences in France, Political Science at the Montesquieu Bordeaux IV University also in France, and also in Education Theory and History at the Murcia University in Spain. He is presently carrying out a doctorate in Murcia on Education Sciences, as well as lecturing in a Master Class on “’Gender and Equality”’. It is also worth mentioning his experience as professor in numerous workshops and courses across Spain and abroad, as well as having published extensively in specialised magazines and books.

**

3.The Euphoria of African Cultures

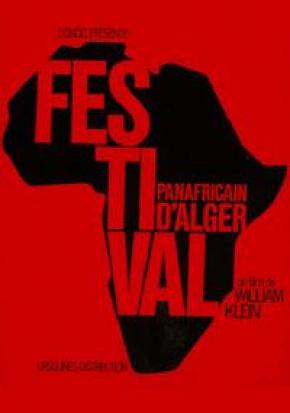

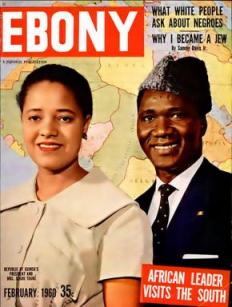

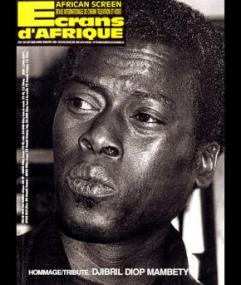

Another of the essential elements within this period is, without a doubt, the re-establishment of African cultures. Independence gave an unprecedented impulse to artistic and cultural life all over the continent. Some states encouraged cultural activity with the political will of providing an identity to the foundations of the new sovereign state by means of creating and backing permanent institutions such as ballets, orchestras and national theatres, and with the celebration of huge national cultural events with international vocation. FESTIVAL PANAFRICAIN D'ALGER William Klein

FESTIVAL PANAFRICAIN D'ALGER William Klein

One of the most emblematic events was the First World Festival of Black Arts held in Dakar in 1966, where, for the first time ever, all the artistic creators from the Black World were present; Afro-American jazz musicians and Dogon ballet dancers, Senegalese sculptors and Brazilian painters. The festival’s political goal was to effectively promote each country as a cultural destiny, but also to endorse the whole continent as one.  First World Festival of Black Arts held in Dakar in 1966

First World Festival of Black Arts held in Dakar in 1966

In the same manner, the Algiers Pan-African Festival stands out. First held in 1969, seven years after the decolonization of Algeria, artists from all over the continent and from the United States met to celebrate African culture after a lengthy period of suffering. Among the artists who participated were Miriam Makeba, Nina Simone, Ousmane Sembène… Numerous leaders of independence movements and representatives of the Black Panthers were also present, lending to this event an activist and revolutionary character.

We must not forget that the re-establishment of African cultures interweaved with the equal civil rights movements and the struggle for the abolition of racial segregation in the United States. Those movements had an extremely influential and powerful cultural arena. Fespaco, Burquina FassoAs regards the seventh art, we cannot forget FESPACO (Pan-African Cinema and Television Festival of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso). Following in the footsteps of the Carthage Cinematographic Encounters, held for the first time in 1966, a week of African Cinema took place in Ouagadougou in 1969. The favorable political practice of the Burkina Faso Government swayed the filmmakers, united since 1970 around the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), to establish what would become FESPACO in the capital. Under Senegalese Ababacar Samb Makharam’s leadership, FEPACI was militant and Pan-Africanist. Cinema was to be used as a freeing tool in colonized countries and as a stepping board towards the complete unity of the continent. The enthusiasm and hope it awoke both in the public and in African filmmakers led the authorities to institutionalize the festival in January 1972.

Fespaco, Burquina FassoAs regards the seventh art, we cannot forget FESPACO (Pan-African Cinema and Television Festival of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso). Following in the footsteps of the Carthage Cinematographic Encounters, held for the first time in 1966, a week of African Cinema took place in Ouagadougou in 1969. The favorable political practice of the Burkina Faso Government swayed the filmmakers, united since 1970 around the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), to establish what would become FESPACO in the capital. Under Senegalese Ababacar Samb Makharam’s leadership, FEPACI was militant and Pan-Africanist. Cinema was to be used as a freeing tool in colonized countries and as a stepping board towards the complete unity of the continent. The enthusiasm and hope it awoke both in the public and in African filmmakers led the authorities to institutionalize the festival in January 1972.

The case of the Bembeya Jazz orchestra is another interesting example. This music formation that emerged in a village in the middle of the tropical forest in Guinea became the champion for Sekou Touré’s Guinean revolution and made Africa vibrate to Guinean rhythms. Sekou-Touré

Sekou-Touré

Culture, during those years, was in fact at the height of the political and social aspirations of the new emerging African states. However, nowadays, the dream seemed to have vanished…

Babacar Diop. He works as a journalist for the daily newspaper “Le Soleil”. He has a Journalism degree (DSJ) and a M.A. in Information Science and Communications from the Information Science and Technology Studies Centre (CESTI), Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar. He also works as a consultant for the cultural intermediation network, “Groupe 30 Afrique”. Actually he is the president of the Facc (Federation Africaine de la Critique Cinématographique).

**

CINEMA TO CONSTRUCT AND EXPLORE A NEW IDENTITY

3. Ideology, Ethics: Re-apropriation of Outlook and Though process

The countries that obtained their independence in the sixties heralded the birth of African cinema, a cinema that adopted a political perspective and re-appropriated a vision of itself opposed to the colonial and ethnographic vision with which Europeans saw Africa.

Until the arrival of independence, Europeans were the only ones who had the right to express their view of Africa. In former Francophone colonies, the Laval decree stated that the Administration had to authorize any filming taking place in the colonies and, of course, the authorization was never given to an African. However, Africa was the ideal film set during the colonial period to satisfy Western audiences’ cravings for the exotic and the mysterious. Colonial movies, filmed with the image of colonial culture, denied African values, social systems and culture, trying to legitimize the civilizing benefits of colonial presence. The new image of domesticated, faithful Africans projected onto the screen after African soldiers participated in World War I was just as dehumanizing as ever.

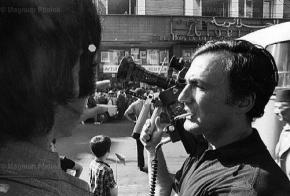

After World War II, and led by Marcel Griaule, the West started to view Africa in a different way by means of ethnographic films. No doubt, it is a point of view that did its best to respect Africans, but its sole purpose was to document traditions and gather information for educational motives. Jean Rouch’s work commenced in full anti-colonial turmoil, with his innovating “transe method”. 16mm camera on the shoulder and microphone in hand, he tried to offer a detailed vision in which the filmmaker/spectator participated in what he observed. Nevertheless, this method of observation would make the pioneers of African cinema consider Rouch’s work films that looked down on them, with images in which Africans are studied as if they were bugs, enclosed in cultural specifications that ridiculed them.

From the moment they were able to hold a camera, the first African filmmakers were aware that their most urgent mission was to re-appropriate the vision of themselves to be able to decolonize the thinking process and reaffirm an identity that would make it possible to build a new nation. The African cinema born in the new independences in the sixties was surrounded by social and political commitment, as well as cultural and identity vindication.

Opposite the external observation of an ethnologist such as Jean Rouch who studied traditions, the new African directors showed essential values within the logic of a quest, of a return to their origins to reaffirm their identity. It was no longer about describing customs and usages in a scientific manner as the ethnologist did; it was about drinking from pre-colonial waters to reencounter the dignity the colonial era had stripped them of. In the film Kaddu Beykat (Lettre Paysanne/Letter From My Village), Safi Faye amply describes the daily life of a Serere village, although it is actually a vision from within.

The pioneer’s films were, above all, political, didactic and militant. These are Sembène Ousmane’s “night classes”, films destined to denounce injustice, starting with the injustices committed by the colonization (for example, La Noire de…, 1965), and then to reencounter dignity and Africanism, recovering fundamental values to erect a new society.

African filmmakers got organized. In 1970 they created the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers thanks to Ababacar Samb Makharam’s drive. His discourse was militant and Pan-African, and the FEPACI rejected commercial films as well as confronting neo-colonialism and imperialism.

However, ideology impregnated the discourse on cinema less than it did the films themselves. As Sembène Ousmane said: “(Cinema) is a form of political action, but I want to make it clear that (…) I don’t make ‘pamphlet’ cinema (…).” The social commitment of the first filmmakers centered on their desire to change the social order by reflecting a cultural universe in which the African public could recognize itself and get involved. This explains the tendency to include a documentary aspect in fiction films, lending pragmatism to politics. Although African cinema was soundly linked to the ideologies developed by the great founding figures of the time, filmmakers, contrary to many leaders, did not preach philosophies from foreign lands. What’s more, a critical outlook of the new independent society quickly replaced the denouncement of injustices committed by colonial society: Mimicry of elitist groups, social inequality, and the birth of African bourgeoisie…

Sembène Ousmane

Sembène Ousmane

Awam Amkpa. Associate Professor and Academic Director at New York University, division Tish School of the Arts. Author of several books and articles

in books and journals on Modernisms in Theatre, Postcolonial Theatre, Black

Atlantic Issues, and Film studies. Director of film documentaries.

4. Cinema and revolution / Cinema and Socialism

Lenin understood that “cinema is one of the most important forms of art”, because it is very popular and can transmit a clear message to an important part of the population very easily. The Soviet Union understood that cinema was an unparalleled unofficial propaganda instrument to promote new socialism.

During the sixties, in countries still colonized, especially those speaking Portuguese, and in Algeria beforehand, an anti-colonial cinema destined to denounce the atrocities of colonial repression and make them known internationally by means of the television channels in socialist countries that supported the independence movements came into being.

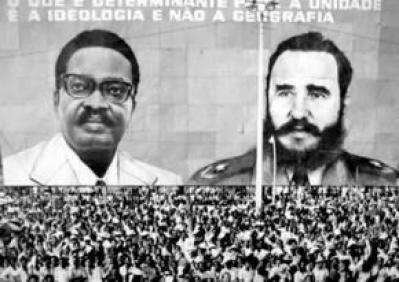

In those countries that came into independence later, especially in Angola and Mozambique, the new socialist governments were completely in charge of film production and diffusion, and its organization, aware that it represented an instrument to build and consolidate socialism. They needed propagandistic and informative films to set the foundations and start to build a new nation.

The goal of this conference is to analyze how cinema, when conceived from an ideological point of view, was first used as an instrument for freedom and then, later, as a propaganda tool becoming a reflection of the utopia prevailing in young nations under construction.

uma odisseia em África, by Jihan El-Tahri

uma odisseia em África, by Jihan El-Tahri

In Algeria, national cinema came into being during the war of liberation. René Vautier, bard of committed cinema who joined the Algerian maquis, was the first to film images of the maquis themselves. In 1957, a small group of “Fellagas” with very meager concepts of the profession, decided to form a shooting crew and created the cinematographic cell of the National Liberation Army. They managed to produce four programs on the daily life of the maquis and, what’s more, they filmed the “Fellaga” attack on the Ouenza mines, stronghold of colonization, which was then shown on television in socialist countries. In 1960, a genuine cinematographic production organization was born by means of the founding of a film committee dependent on the Provisional Government of the Republic of Algeria (GPRA) and, later, by means of the creation of a Cinema Service of the GPRA, as well as the formation of a Cinema Service of the National Liberation Army (ALN) after Algeria’s independence in 1962.

Reunited in Algeria in 1969, the filmmakers who gathered to found FEPACI assigned themselves the prophetic mission of using cinema as an instrument to free colonized countries. Their intention was to create a new aesthetic and film semi-documentaries denouncing any and all colonial regimes. The Portuguese speaking countries were those that most developed anti-colonial propaganda cinema during the sixties, using the revolutionary ideas of Frantz Fanon and Amílcar Cabral. These films were distributed in Europe by means of the Mozambique People’s Support Committees.

In Angola, since the sixties and within the framework of the colonial war, images of the anti-colonial guerrilla filmed by the Department of Information and Propaganda belonging to the “Movimento Popular de Liberaçao de Angola” (The People’s Angolan Liberation Movement) started to proliferate. It was the vanguard of intervention cinema that would consolidate itself with the arrival of Independence.

Post independence socialist cinema formed part of the State, who entirely took charge of film production by means of such institutions as the People’s Television of Angola, the Angolan Institute of Cinema and the National Cinema Lab. The goal behind the intensive formation of professionals in the film cooperative Promocine and at the People’s Television of Angola (TPA) was to film a new country, the people’s mobilizations, the professional conditions of the workers and political-military activities. As an example, we have the films made by filmmakers such as Ruy Duarte de Carvalho and Asdrubal Rebelo.

In Mozambique, where the FRELIMO (Mozambique Liberation Front) understood the importance of cinema as an international political accusation tool, cinema was sponsored by utopia. Once again, it was about communicating the new values of Independence and the Socialist Revolution. Samora Michel’s government created the National Institute of Cinema (INC) and entrusted the direction to Ruy Guerra, one of the founders of the Brazilian cinema novo. From an optimistic perspective, the INC set its sights on producing and diffusing at a national level: To film the people and give those images back to the people. It even considered taking an active involvement to change the progress of cinema on the entire African continent. And so was born Kuxa Kanema, the weekly cinema journal that gave birth to Mozambique cinema, based on documentary images that represented the dreams of a young nation under construction.

Jihan El-Tahri. Born in Beirut, she is French and Egyptian. After studying Political Sciences at the American University in Cairo, she worked as a correspondent on current politics in the Near East and Africa. In 1992, she filmed Osama Bin Laden’s training camps in Sudan. Writer, director and producer, she has produced and directed documentaries for French Television

and the BBC, for which she has been granted numerous prizes and been nominated twice to the Emmys.

João Ribeiro. Born in Zambezia, Mozambique. This school teacher began to

shoot short films in 1982. He also collaborated with Mozambique’s experimental television, worked with the provincial delegation of the National Cinema Institute (INC), and afterwards, in the INC archives in Maputo. He was appointed INC production coordinator in 1989. In 1990 he travelled to Cuba to study Film Direction and Production at the San Antonio de los Baños International Cinema School. Back in Mozambique, he directed his first short film, Fagota, and produced several other films. He has participated in many workshops and has lectured on Mozambican cinema and Africa in general. He has recently finished his first feature film, The last flight of the flamingo, a Spanish-Portuguese-Mozambican co-production.

Utopia and Reality: 50 years of African Independencies? - films

CUBA UNE ODYSSEE AFRICAINE Jihan El Tahri France

FRANTZ FANON, UN COMBAT, UNE VIE, UNE OEUVRE - Cheikh Djemai, Algeria-Tunisia-France

MANDABI Sembène Ousmane, Senegal-France

XALA Sembène Ousmane, Senegal

FESTIVAL PANAFRICAIN D’ALGER William Klein, Algerie-France-Germany

AFRIQUE 50 René Vautier, France

AVOIR 20 DANS LES AURES René Vautier, France

PEUPLE EN MARCHE René Vautier, Algeria

LE DAMIER - PAPA NATIONAL OYÉ Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda, DR of Congo- Gabon-France

DEMAIN A NANGUILA Joris Ivens, Mali

AMILCAR CABRAL Ana Ramos, Lisboa Cape Verde-Portugal

AIME CESAIRE, LE MASQUE DES MOTS Sarah Maldoror, France

ELDRIDGE CLEAVER, BLACK PANTHER William Klein, Algeria

LUMUMBA LA MORT DU PROPHÈTE Raoul Peck, DR of Congo-Switz.

LUMIERES NOIRES Bob Swaim, France

MORTU NEGA Flora Gomes, Guinea-Bissau

SOLEIL Ô Med Hondo, Mauritania

LA BATTAGLIA DI ALGERI Gillo Pontecorvo, Algeria-Italy

FESTIVAL PANAFRICAIN D'ALGER William Klein,

FESTIVAL PANAFRICAIN D'ALGER William Klein,

conferences

conferences

Retrospective Idrissa Ouedraogo

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of the Cannes’ Jury Award for his film “Tilaï”, FCAT 2010 will show a complete retrospective of the filmmaker from Burkina. The 11 titles of this master retrospective are:

TILAI Burkina Faso-Switz.-France

SAMBA TRAORE Burkina Faso-Switz.-France

YAM DAABO Burkina Faso-France

YAABA Burkina Faso-France-Switz.-Germany

KINI & ADAMS Burkina Faso-France-UK

A KARIM NA SALA Burkina Faso-France

LE CRI DU COEUR Burkina Faso-France

LA COLÈRE DES DIEUX Burkina Faso-France

ISSA LE TISSERAND Burkina-France

LES ECUELLES Burkina Faso

LES PARIAS DU CINEMA Burkina Faso-Switzerland

In and out of Nollywood:

The audiovisual production in Nigeria is the second

in the world, behind Bollywood and before Hollywood. In last few years, certain

films from the Nigerian audiovisual production have improved their the artistic

quality, moving away from the usual Nollywood production (larger budgets,

longer shooting schedules) in an effort to become internationally acknowledged.

This is the time for the FCAT to dedicate a section to the “Nollywood

phenomenon”. This space will try to analyse the impact that this phenomenon

may have on the future of African cinema in general. Four films will explore this section and film industry:

ARAROMIRE Kunle Afolayan, Nigeria

THIS IS NOLLYWOOD Franco Sacchi, USA

LILIES OF THE GHETTO Ubaka Joseph Ugochukwu, Nigeria

ARUGBA Tunde Kelani, Nigeria

The African Diaspora in Cuba.

After two years without paying attention to the African diaspora, the FCAT has realised… Who, besides an African Film Festival in Spain, can act best as a nexus between three continents? Africa, Europe and Latin America. This film selection was commissioned by the International Film Festival of La Habana.

12 films constitute this film section:

LA ULTIMA CENA Tomás Gutiérrez Alea

HISTORIA DE UN BALLET José Massip

EL OTRO FRANCISCO Sergio Giral

COFFEA ARÁBIGA Nicolás Guillén Landrián

EL MENSAJERO DE LOS DIOSES Rigoberto López

MARÍA ANTONIA Sergio Giral

OBATALEO Humberto Solás

WIFREDO LAM Humberto Solás

NOSOTROS LA MÚSICA Rogelio París

EL FANGUITO Jorge Luís Sánchez

RAZA Eric Corvalán

DE CIERTA MANERA Sara Gómez

**

ORGANISATION: AL-TARAB

Director: Mane Cisneros Manrique | mane@fcat.es

Programming: Marion Berger y Mane Cisneros | marionb@fcat.es

Administration: Pierangelo Vallaperta

FCAT Professional Space: Carlos A. Domínguez.

Paralel Activities: Gaetano Gualdo, Sandra M. Maunac, Mónica Santos.

Press: Juan León Moriche +34/695 499026 gabineteprensa@fcat.es

Federico Olivieri (international media) +34/677112439 federico@fcat.es

Rut Mingorance +34/660503942 comunicacion@fcat.es