The Culture of Coloniality

BUALA is pleased to announce the launch of a series of re-publications of texts written for L’InternationaleOnline issue Decolonising Museums.

********

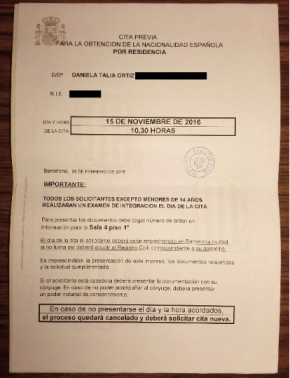

On Saturday 13 October 2012, the day after the celebration of the National Day of Spain and its insulting commemoration of the start of the colonial process, the Department of State Records published a document stating the conditions that the migrant populations would be required to meet if they wished to obtain equal rights as citizens through the only possible channel available: by obtaining Spanish nationality.

The first page of the document decrees that “the appropriate level of integration into Spanish society is not limited to an acceptable knowledge of the language, but also requires knowledge of the institutions and traditions, and the adoption of the Spanish way of life”. The document encourages the authority in charge of this process of bureaucratic abuse to specify whether or not migrant applicants are sufficiently integrated.

Appointment request form for Spanish citizenship application, 'Please note All applicants aged 14 and over will be required to sit an integration exam on the day of the appointment.'Similarly, in Catalonia a new law – ironically known as the ‘welcome law’ – was introduced as part of the process of construction of sovereignty. This law basically consists of a series of requests on financial and labour issues, which applicants must accomplish in order to obtain a residence permit or family reunification. In addition, the law states that they are required to prove their integration by participating in courses, an interview, and above all showing a basic knowledge of both Spanish and Catalan.

Appointment request form for Spanish citizenship application, 'Please note All applicants aged 14 and over will be required to sit an integration exam on the day of the appointment.'Similarly, in Catalonia a new law – ironically known as the ‘welcome law’ – was introduced as part of the process of construction of sovereignty. This law basically consists of a series of requests on financial and labour issues, which applicants must accomplish in order to obtain a residence permit or family reunification. In addition, the law states that they are required to prove their integration by participating in courses, an interview, and above all showing a basic knowledge of both Spanish and Catalan.

Imposing integration on the migrant populations is actually just a tool to strengthen the process of colonisation of individuals, like myself, who come from subjugated countries. Several politicians in Catalonia defended the prerequisite knowledge of Catalan – a condition that only applies to the migrant populations – based on the argument of maintaining social cohesion through the use of a common language, even though this common language is obviously not a prerequisite for people from Germany or Madrid.

As I mentioned in another article on this matter, if the Spanish state demands that people from countries like Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador become integrated into a society that celebrates its National Day on 12 October each year, and where there are fourteen monuments commemorating Christopher Columbus, many of us end up believing that we are actually being asked to take the same position in regard to Spanish society as the indigenous person kneeling before the priest Bernardo Boyl represented on the pedestal of the monument to Columbus in Barcelona. The requirement to integrate begins with an aggressive questioning, in the negative sense, of the knowledge, traditions and cultures of the ones that come from the former colonies, and ends by determining, through the bureaucratic system, whether or not you are granted the right to not be deported and to remain in this territory.

Daniela Ortiz, Réplica, 12 October 2014, action carried out during the Spanish National Day celebrations.

In 2015, the Spanish government granted the Instituto Cervantes, which describes itself as “an institution for the promotion, teaching, and dissemination of Spanish and Hispanic culture”, the authority to draft the questions for the citizenship tests. The perspective on national identity, and the knowledge that a Spanish citizen would be expected to know do not differ much from the parameters used by the authorities in previous years. Questions such as “what is celebrated on 12 October?”, “what are Spain’s borders?” and “what were the Spanish viceroyalties in colonised territories?” show how the coloniality of knowledge is established in all its strength, given that the correct answers required to pass the test are those that defend the colonial and imperial nature of Spanish identity. This means that a person from a context in which the Day of Indigenous Resistance is celebrated on 12 October, for example, has to answer that the significance of this date is the fact that it is Spain’s National Day. Similarly, a person from Morocco has to state that the colonial territories of Ceuta and Melilla are Spanish, and so on. The migrant subject who attempts to obtain citizenship rights must accept and repeat as legitimate the narratives that place him or her in an inferior position.

You may be wondering what all of this abusive bureaucratic red tape established by the migratory control system has to do with decolonising a museum. Apart from the fact that coloniality is precisely one of the main elements that the museum – as one of the key spaces for the construction of Eurocentrism – shares with the migratory control system as the backbone of coloniality in Europe, there is also the issue that what migrants are asked to learn and accept is culture, and at the same time museums supposedly establish the legitimation frameworks that define what culture is or is not, and how that culture is understood and disseminated.

When I was asked to participate in the seminar “Decolonising the Museum” organised by the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), and again now that I have been invited to write about the subject, I do so based on the conviction that it is essential to note that in all the bureaucratic red tape described above, there is a striking absence of any responsibility given or taken by spaces and agents that are supposedly specialised in cultural construction and dissemination. While the Instituto Cervantes has already stepped into its role as inquisitor, institutions such as the Museo Reina Sofía, MACBA, MUSAC, and particularly an institution such as La Virreina, have been deafeningly silent in regard to how representatives of the migratory control system use notions such as culture to determine whether a migrant person is expelled or permitted to stay.

The fact that cultural institutions do not express any resistance to culture being used to reinforce xenophobic and racial segregation practices by means of the discourse of integration makes it impossible to imagine how a process of decolonisation could take place simply through exhibitions, debates and talks that regularly appear in their programmes of activities. Unless there is a connection with the territories in which coloniality currently operates in all its violence in the European context, migrants may end up having to learn the name of the Spanish artists who exhibit in these museums in order to answer questions in the citizenship test.

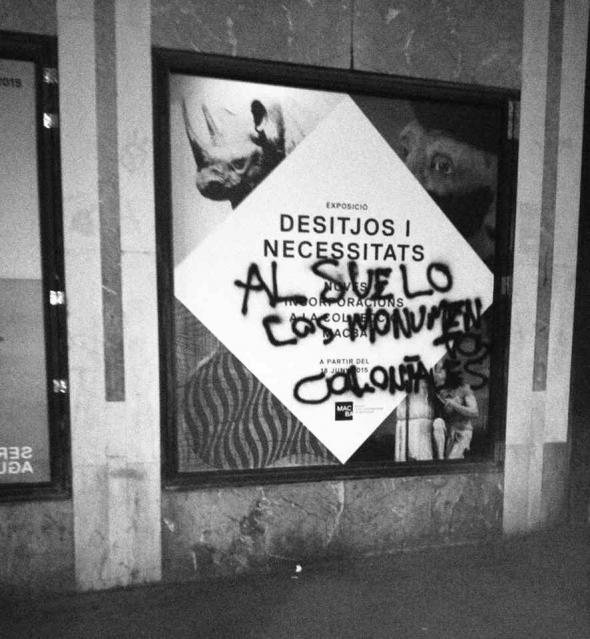

Desires and Necessities. Down with colonial monuments, 2015.

Desires and Necessities. Down with colonial monuments, 2015.

I realise that the silence of cultural institutions may stem from their supposed political neutrality, that complex neutrality that leads, for example, to programme an exhibition financed by the embassy of the colonial state of Israel, publish an exhibition information sheet where the word Palestine, following Golda Meir’s style, is not mentioned but the words Jordan and Israel are, and throw out a Palestinian refugee artist who was carrying out an artistic action1 at the opening in protest against the direct involvement of the Israeli Embassy in this cultural activity. The same political neutrality that leads them to staunchly defend the very European freedom of expression in response to the censorship of an artwork that includes the image of king Juan Carlos I but not to not ask questions such as those raised from non-institutional spaces in relation to the colonial humiliation of Domitila Barrios in that same work (see). That political neutrality that allows a museum to call an itinerary through some of its collection “Meditarrani” and to describe Mediterranean lands as a “hospitable haven for immigrants”. That political neutrality that leads to situations where the exhibition of a series of clearly political artistic projects ends up being accompanied by interpretations issued by the museum that give the visitor precisely the opposite information to what the participating artist is trying to say. This recently occurred with the information sheet that explained the project Estat Nació. Part I [Nation State, Part I, 2014] in the exhibition Desires and Necessities: “Daniela Ortiz + Xose Quiroga propose a journey through the streets of Barcelona to identify the monuments and buildings that celebrate our city’s colonial history and its associations with slavery, a city where the values of tolerance and openness to global culture contrast with the commemoration of those who grew rich on the trade in human beings or the colonial endeavour”.

Was the person who wrote the text referring to the “values of tolerance and openness to global culture” in the city of Barcelona, where migrants who work in public spaces are violently persecuted and arrested? Or to the values of tolerance and openness to global culture in the city of Barcelona, where migrants are required to pass integration and language tests in order to obtain a residence permit that allows them to avoid being totally left out of civic life or end up being deported? And that last point is where I really question the political intentions of the person who wrote the information sheet, because the project Estat Nació. Part I includes a video, which was not exhibited obviously, that challenges current policies in regard to the obligatory integration of migrants in Catalonia.

Daniela Ortiz + Xose Quiroga, Estat Nació. Part I, 2014, video A group of migrants learn to pronounce Catalan correctly by repeating xenophobic discourses.

In a context of extreme colonial violence which the migrant and refugee populations are currently experiencing in Europe, it can be useful and necessary to think about decolonising the museum. But there is a danger that it may become a matter that is totally out of context and even insulting if it does not place at its centre a discussion concerning the situation that is currently imposed by Europe’s migratory control system on which people come from the former colonies. Decolonising a cultural institution does not just mean considering the matter and organising exhibitions and seminars. In the current context, decolonising a museum requires a constant effort to take a position in regard to the migratory control system; it requires accepting that it is impossible to continue programming activities and events while there is a total normalisation of the existence of Migrant Detention Centres, forced deportation flights on a mass and individual scale, individuals with semi-rights and anti-rights, and situations of extreme violence in border zones which are the local contexts where these projects are presented. Decolonising a museum means sending letters to the Ministry of Interior, organising press conferences to condemn the use of culture in the discourse of integration, making the legal apparatus of the museum available to persecuted people; it means acknowledging the level of urgency imposed in the European context by the backbone of coloniality.

Published in Decolonizing Museums, L’Internationale Online, Issue 2, September 2015.

***********************************************

Decolonising Museums is the second thematic publication of L’Internationale Online; it addresses colonial legacies and mindsets, which are still so rooted and present today in the museum institutions in Europe and beyond. The publication draws from the conference Decolonising the Museum which took place at MACBA in Barcelona, 27-29 November 2014 (among the contributors to this thematic issue, Clémentine Deliss, Daniela Ortiz and Francisco Godoy Vega participated at this seminar), and offers new essays, responding to texts published on the online platform earlier this year. L’Internationale is a confederation of six major European modern and contemporary art institutions and partners. L’Internationale proposes a space for art within a non-hierarchical and decentralised internationalism, based on the values of difference and horizontal exchange among a constellation of cultural agents, locally rooted and globally connected. One of the main sites where research and debate related to the current project of L’Internationale, the five-year programme (2013-2017) titled The Uses of Art – The Legacy of 1848 and 1989, takes place is on the newly developed platform: L’Internationale Online.

- 1. Firas Shehadeh, Palestinian sand dance, 2014, single channel video/ sound installation and digital print. Courtesy the artist