The World is an Island

Olavo Amado Life as a labyrinth

Galeria 23 – Amsterdam

March 23 – April 20, 2011

Ritmos em sequencias repetidas, 2008, acryl op doek, drieluik, (3 x) 50 x 50 cm. (foto SBK Amsterdam / Rob Moorees).

Ritmos em sequencias repetidas, 2008, acryl op doek, drieluik, (3 x) 50 x 50 cm. (foto SBK Amsterdam / Rob Moorees).

Ten years ago, Olavo Amado joined a group to clean the pavements near his house. The following day, he walked to Espaço Teia D’Arte in order to try his hand at painting. João Carlos Silva had asked the young people in the Riboque neighbourhood in São Tomé to discover what was hidden under the paving stones that people stepped on everyday, and then to go the next day to Espaço Teia D’Arte to paint. In the crisscrossing lines of a pavement and those of a canvas, Olavo found his labyrinth and lost himself painting.

For an islander, the configuration of a labyrinth is not a strange one. An island is a labyrinth. It has no walls and we easily reach its limits and see the horizon, but there is no way out. We can only leave the island by sea or by air, but then only to replace it with another piece of land. The limitations of an island are far better than to drift at sea or in the air.

Olavo Amado in Amsterdam, februari 2011 (foto Giovanni Piesco)Olavo would visit the Feira do Ponte market in the city of São Tomé and made several series of paintings of women selling their goods there. He would talk with them while he drew his sketches and portrayed them in their public life as market vendors. In his paintings, women carry pots and baskets on their heads and children on their backs as they go about their daily struggle to earn a living and care for their families. The everyday existence of these women confronts and superimposes their figurative impact, and their forms are freed to depict the narrow corridors in the market. The women are shaped along the pathways they tread day after day, and later the pathways are returned to them in a multitude of longer and more complex inner pathways. The market has been demolished but the labyrinths remain even without walls.

Olavo Amado in Amsterdam, februari 2011 (foto Giovanni Piesco)Olavo would visit the Feira do Ponte market in the city of São Tomé and made several series of paintings of women selling their goods there. He would talk with them while he drew his sketches and portrayed them in their public life as market vendors. In his paintings, women carry pots and baskets on their heads and children on their backs as they go about their daily struggle to earn a living and care for their families. The everyday existence of these women confronts and superimposes their figurative impact, and their forms are freed to depict the narrow corridors in the market. The women are shaped along the pathways they tread day after day, and later the pathways are returned to them in a multitude of longer and more complex inner pathways. The market has been demolished but the labyrinths remain even without walls.

Knowledge of pathways, an imaginary knowledge of labyrinths, creates a sense of familiarity and makes prison less hard. To know where pathways lead, even if not to an exit, is better than to set off in any direction. Having every possibility creates a desert. Confronting limits is more bearable that to be adrift and aimless, that is why a shipwrecked person tries to reach land as they cannot survive in high seas.

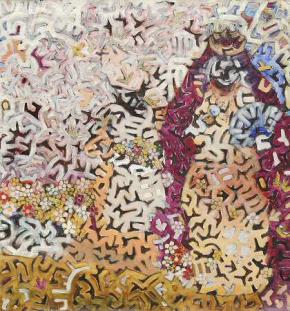

Rainha e Dama do Chiloli, 2011, acryl op doek, 150 x 140 cm. (foto SBK Amsterdam / Rob Moorees)This is likewise the creative person’s endeavour to escape aimlessness and become involved in a labyrinth of ideas even if unable to get a complete view of the way. To go along pathways trying out solutions, always in search of things and checking whether there is a way out of an alleyway. Art is adding up pathways in the labyrinth, it is worth the enthusiasm of lost steps and lives off the meaning of a search. The pathway always offers more than the destination.

Rainha e Dama do Chiloli, 2011, acryl op doek, 150 x 140 cm. (foto SBK Amsterdam / Rob Moorees)This is likewise the creative person’s endeavour to escape aimlessness and become involved in a labyrinth of ideas even if unable to get a complete view of the way. To go along pathways trying out solutions, always in search of things and checking whether there is a way out of an alleyway. Art is adding up pathways in the labyrinth, it is worth the enthusiasm of lost steps and lives off the meaning of a search. The pathway always offers more than the destination.

Olavo says there are many entrances and few exits. The way out of a labyrinth could be the entrance into another labyrinth and each of them is a metaphor for others. Olavo was transforming women vendors at the market and lovers wrapped together in graphic compositions suggestive of labyrinths. The process is not an immediate merging of body and labyrinth. Olavo has been experimenting various stages of merging bodies until they dematerialise to become abstract lines, by going on new pathways, stepping anew on old roads in a search that renovates and makes us believe.

The labyrinth sets limits, but within them it allows total freedom.